I’m a Chicago homie — long removed but never really gone — so don’t expect objectivity, but a recent visit proved my native metropolis is #1 in America and maybe everywhere for its active, creative, meaningful, almost-economically-viable, neighborhood-rooted, exploratory and world class jazz. I say this even as my dearly adopted New York City kickstarts as freshly energized a fall season as any I recall.

Jazz is the lifeblood of Chicago in a way it ain’t in NYC, at least not right now. Jazz-soul-blues is Chicago’s street music. Chicago’s citizens — not just its visitors — seem to consider jazz this music their personal due. It’s what you hear at O’Hare going in and out of town.

This is in large part but not at all completely or originally because of events like the 31st annual free Chicago Jazz Festival held over Labor Day weekend, sponsored this time by CareFusion and produced as ever by the City of Chicago Mayor’s Office of Special Events while programmed by the non-profit grassroots Jazz Institute of Chicago which has been generously befriended by the philanthropic Chicago Jazz Partnership (comprising The Boeing Company, Kraft Foods, Bank One, Chicago Community Trust and other firms).  Featured music was of all jazz eras and forms — from recollections of Benny Goodman (by clarinetist Buddy DeFranco, saxophonist Eric Schneider and the avant group Klang) and pianist Art Tatum (by Johnny O’Neal) to provocations and revelations from festival artist-in-residence Muhal Richard Abrams and fellow stalwarts from the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) Fred Anderson, Ari Brown, Hamid Drake, George E. Lewis, Nicole Mitchell, Roscoe Mitchell and Jeff Parker, among others.

There was local brilliance by bopside paterfamilias Von Freeman and hard beats laid down by such as drummer Ted Sirota (who likes a touch of reggae in his Rebel Souls). There was internationalism from pianist Amina Figarova and her Netherlands-based sextet and pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba with his Cuban-American quintet. There were standing ovations for each of three very different official fest performances by Abrams — his solo piano recital (ruminative “cosmic tones for mental therapy,” per Sun Ra), the Streaming trio of R. Mitchell and Lewis, the architecturally distinctive “SPIRALVIEW” performed by an orchestra trumpeter Art Hoyle cherry-picked — as well as for the raging yet synchronized Dave Holland Big Band.

Dee Alexander, Chicago’s emerging diva, sang her own lyrics too laden with fluttery imagery for her substantial self;Â Archie Shepp, in the ’60s a fierce saxist and social critic, stung the crowd — in the tens of thousands of listeners comfortably and completely diversified by age, race, gender and presumably income brackets — with his ode “Steam” to a cousin murdered in Philadelphia, which included a piercing soprano solo. William Parker, New York bassist, led “The Inside Songs of Curtis Mayfield,” an interpretation of a Chi-town favorite son in which Amiri Baraka delivered caustic poetry while Leena Conquest sang the ever-hopeful lyrics of “People Get Ready,” Sabir Mateen wailed in the screech octave as saxman Darryl Foster and trumpeter Lewis Barnes riffed, Dave Burrell pounded the piano and Hamid Drake provided backbeat that had attendees dancing in the aisles. Someone tweeted “According to the band, Freddy is dead. #jazzlives” Everyone was getting along.

Incredible to me, because growing up in the ’60s under the reign of Richard J. Daley music in the parks was a battleground issue. The Chicago Symphony offered free summer concerts, and there was a historic blues fest in the mid ’60s, but after some jerks throwing bottles prior to a delayed Sly Stone show set off an audience rampage in which cop cars were overturned and burned, that was the end of such festivities for a dozen years. When one-term maverick Mayor Jane Byrne allowed a jazz fest in Grant Park and a multi-ethnic Chicagofest on Navy Pier she introduced conditions that hadn’t previously been encouraged for white and black and Latino Chicagoans to mingle for family entertainment, arguably leading to the election of the city’s first black mayor Harold Washington and who knows, maybe the rise of a community organizer from the South Side to the position of President of the United States.

Jazz has worked that way in Chicago, at the core of things if not obviously so, since Jelly Roll, King Oliver and the rest imported it from New Orleans in the ’20s. There is a long history of music applied for societal purposes in Chicago even prior to jazz — read Sounds of Reform: Progressivism & Music in Chicago, 1873-1935 by Derek Vaillant, which is fascinating in that the preferences of listeners always, eventually, trumped plans set forth by those who thought they had better taste. Once introduced to Chicago jazz jes’ grew, nurtured by the gangsters and speakeasy-goers, blossomed during the Great Depression as it was broadcast coast to coast, asserted its centrality in the post-war years with the blues in all its guises and through the ’50s and ’60s to this day.Â

You don’t need a jazz festival to be immersed in the music in Chicago, one is always surrounded by it– like in New Orleans pre-flood (I can’t speak from recent experience, not having been back since Katrina). Driving around, I heard the strangest jazz on WNUR-FM and more mainstream but out-of-the-ordinary choices from WDCB-FM. I visited the Chicago Jazz Archive, housed in the Special Collections research center of Regenstein Library at UniversityÂ

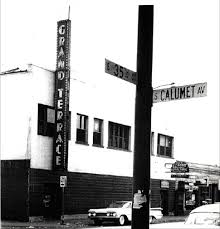

of Chicago, and looked at photos of the Royal Garden and Grand Terrace ballrooms — shrines sitting like normal buildings on corners of typical streets. I listened to Lil Armstrong speak from a digitally archived radio interview, glanced over ephemera from the early days of Sun Ra’s Arkestra and El Saturn Records, read issues of the AACM’s 1960s-’70s mimeographed newsletter. I have some of those, from when I went to AACM concerts around U of C in the ’60s . Ok, it’s historic — not just quotidian Chicago stuff.

Some of the most earnest and inspiring sounds during the week I was back included the impassioned singing of the unique “South Side Songbook” — drawn from the reper

toire of Dinah Washington, Gene Ammons, Nat Cole, et al. — by June Yvonne at City LIfe, a bustling joint on distant south 83rd St.; the extra muscle The Masheen & Co. put into covers of Stevie Wonder’s “Superstitious” and Lou Rawls’ “Tobacco Road” at Red Peppers Masquerade Lounge on 87th; the epically high intensity communication Fred Anderson, Kidd Jordan, Muhal, bassists Henry Grimes and Harrison Bankhead and most-valuable-player Drake laid down at the Velvet Lounge; Ira Sullivan’s annual ministrations as jam master at Joe Segal’s Jazz Showcase (Chris Potter among the sitters-in), the neon-romantic saxes & organ stylings of Sabertooth at the Green Mill, a gig that occurs every Saturday night, midnight to 4 a.m. and was packed with saucy revelers. Like when it was a Capone booze outlet, no?

toire of Dinah Washington, Gene Ammons, Nat Cole, et al. — by June Yvonne at City LIfe, a bustling joint on distant south 83rd St.; the extra muscle The Masheen & Co. put into covers of Stevie Wonder’s “Superstitious” and Lou Rawls’ “Tobacco Road” at Red Peppers Masquerade Lounge on 87th; the epically high intensity communication Fred Anderson, Kidd Jordan, Muhal, bassists Henry Grimes and Harrison Bankhead and most-valuable-player Drake laid down at the Velvet Lounge; Ira Sullivan’s annual ministrations as jam master at Joe Segal’s Jazz Showcase (Chris Potter among the sitters-in), the neon-romantic saxes & organ stylings of Sabertooth at the Green Mill, a gig that occurs every Saturday night, midnight to 4 a.m. and was packed with saucy revelers. Like when it was a Capone booze outlet, no?

We have neighborhood clubs in NYC. And they tend to be scenes unto themselves, similar to  Chicago’s redoubts: little worlds of whirling socializing in which music eases all interactions, provides an ostensible reason for being there, sets the tone and mood for whatever will follow. But there’s something a little starched about NYC’s nightlife, perhaps due to higher cover prices, the Apple’s competitive culture or sheer pretention. In Chicago, it’s not so much that the performers let their hair down as that they never put it up. They come to play, not to pose. They don’t expect much reward in terms of money or fame, though they could use some of each and keep their eyes open for opportunities. The making of music is the main thing. Those onstage do intend to say something. It’s an attitude found elsewhere amongst the jazz youthful, hopeful, idealistic, devoted, deluded, but it is distributed unevenly, in sparing quantities. Fortunately, it is infectious. In Chicago, festivals breed festivals — Hyde Park where the Obamas live puts on its own extravaganza Sept. 26, featuring 40 jazz performances in 13 venues over 15 hours — again, all free, all styles.

Maybe with Ornette Coleman triumphantly waving the flag for such deeply, determinedly individualistic and humanely sociable improvised music at Jazz At Lincoln Center on Sept. 26, New York will take a bold step to reform its musical culture this season to embrace greater freedom from constraining convention, more faith in the imagination, energy for collaboration and a vision of jazz as it really is — exciting, essential — beyond “mere” jazz, the music reduced to clichés. As drummer Bob Moses once told me, it’s not as important to play notes you never played before as to play them so they sound like you never played them before. There is too much staleness in too much jazz currently — nearly every jazz faction bemoans this —  too much reliance upon the past and not enough expectation of the future. I’m eager to hear new music anywhere. Jazz lives, I believe that. The question: Where now?Â

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter

All JBJ posts |