Of all of the things I will write here, this is the idea that is most important. It is central to one of the pillars of creative independence: attitudes. And one of those attitudes involves hierarchical thinking according to which doing your art is certain places is considered more important that doing the same art somewhere else. I call this the Sinatra Imperative — the idea that your creativity is more important if it is done in one of the major metropolises (“If I can make it there / I’ll make it anywhere / It’s up to you / New York, New York”). You may think this is just “natural” or “obvious,” but it actually is one of the major barriers to your freedom to pursue your creativity.

In his inspiring book The Icarus Deception: How High Will You Fly? (which I highly recommend you read), business and creativity leader Seth Godin tells the “true story” of Sarah, who illustrates this concept dramatically in a segment of the book called “Someone Else’s Dreams.” Godin Writes:

In his inspiring book The Icarus Deception: How High Will You Fly? (which I highly recommend you read), business and creativity leader Seth Godin tells the “true story” of Sarah, who illustrates this concept dramatically in a segment of the book called “Someone Else’s Dreams.” Godin Writes:

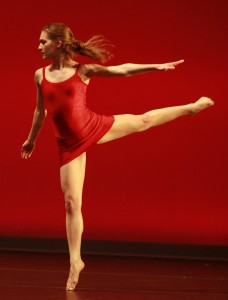

Sarah loves to perform musical theater. She loves the energy of being onstage, the flow of being in the moment, the frisson of feeling the rest of the troupe in sync as she moves.

And yet…

And yet Sarah spends 98 percent of her time trying to be picked. She goes to casting calls, sends out head shots, follows every lead. And then she deals with the heartbreak of rejection, of being hassled or seeing her skills disrespected.

Is this your experience? Do you spend most of your time trying to get a job instead of working on your art? Sarah does this, Godin says,”All so she can be in front of the right audience.” It’s the Sinatra Imperative in action.

Which audience is the right one? The audience of critics and theatergoers and the rest of the authorities. After all, that’s what musical theater is. It’s pinnacle is at City Center and on Broadway, and if she’s lucky, Ben Brantley from the Times will be there and Baryshnikov will be in the audience and the reviewers will like her show and she might even get mentioned. All so she can do it again.

The object, of course, is to perform. But once the Sinatra Imperative kicks in, it isn’t enough simply to perform — it is important where one performs.

This is her agent’s dream and the casting agency’s dream and the director’s dream and the theater owner’s dream and the producer’s dream. It’s a dream that gives money to those who want to put on the next show and gives power to the professionals who can give the nod and, yes, pick someone.

But wait. Sarah’s joy is in the dance. It’s in the moment. Her joy is creating flow.

When we lose track of the real reason we want to create, the real reason we got into the arts in the first place — when we lose track of where the joy is — we find ourselves gradually moving further and further away from our creative energy and we start thinking like an employee: I need this job, oh God I need this show. All because of a belief that certain zip codes are more important than others. Godin goes one:

When we lose track of the real reason we want to create, the real reason we got into the arts in the first place — when we lose track of where the joy is — we find ourselves gradually moving further and further away from our creative energy and we start thinking like an employee: I need this job, oh God I need this show. All because of a belief that certain zip codes are more important than others. Godin goes one:

Strip away all the cruft and what we see is that virtually none of the demeaning work she does to be picked is necessary. What if she performs for the “wrong” audience? What if she follows Banksy’s lead and takes her art to the street? What if she performs in classrooms or prisons or for some (sorry to use air quotes here) “lesser” audience?

What decided that a performance in alternative venues for alternative audiences wasn’t legitimate dance, couldn’t be real art, didn’t create as much joy, wasn’t as real? Who decided that Sarah couldn’t be an impresario and pick herself?

Godin’s answer to this question is devastating. The people who decided are “the people who pick.”

When Sarah chooses herself, when she makes her own art on her own terms, two things happen: She unlocks her ability to make an impact, removing all excuses between her current place and the art she wants to make. And she exposes herself, because now it’s her decision to perform, not the casting director’s. It’s her repertoire that’s being judged, not the dramaturge’s. And most of all, it’s her choice of audience. not the choice of some official, suit-wearing authority figure.”

It’s daunting — suddenly, you are responsible for what you put out there — but it is also invigorating, beause it is your choice. A few pages later, Godin utterly destroys the foundation of the Sinatra Imperative:

You don’t commit to a venue or a medium or a technique. You commit to a path and an impact. Broadway is a venue. Joy through movement is an art. When the venue doesn’t support your art, you can change it without changing your commitment to the journey.

There are many, many places where your art could be celebrated. There are many, many places where people are hungry for your joy, your light, your energy. The only thing stopping you from experiencing this appreciation is a voice you have in your head that says that you need to be picked by certain people and be seen by certain people in order to consider yourself “good.” As if an audience one place is somehow superior to an audience somewhere else.

Once you rid yourself of that voice in your head singing the Sinatra Imperative theme song, you are “free to move about the country,” as Southwestern Airline used to say. You are free to choose the audience who needs you, do the work you want to do, and stop asking permission.

Once you rid yourself of that voice in your head singing the Sinatra Imperative theme song, you are “free to move about the country,” as Southwestern Airline used to say. You are free to choose the audience who needs you, do the work you want to do, and stop asking permission.

It’s not easy. But unless you break free of the Sinatra Imperative and embrace your freedom, artistic independence will never be yours.

As Elsa says, let it go.

A lot of this attitude is woven directly into the higher-ed theatre training programs, though. For example, in the tenure standards at my institution, venues and journals are ranked hierarchically based on prominence, with “Broadway” and “Off Broadway” sitting at the very top and things streaming out beneath them. So even possible mentors are forced to chase this Sinatra delusion in order to keep the jobs they have.

The whole thing, as you noted in your first post here, seems awfully cyclical. Plus, the continued deficiencies of the American theatre are noted and bemoaned on a regular basis; I cannot help but see a connection.

“But what of educators?” I guess is the crux of my question. When staring down the barrel of elimination after 5 years due to “unsatisfactory progress toward tenure,” it’s more than a little difficult to lead by example.

Well, Eric, I guess there are a couple possible pathways. One would be to toe the line until you get tenure, and then step out once you have attained the security. Another would be to create an alternative argument so strong that the committee recognizes your wisdom. But if we just continue to repeat the old message despite its madness, I’m not certain how we can look our students in the eyes.

I can’t begin to describe the exhilarating freedom pulsing through my veins after reading this. Yes, yes, yes. Please keep writing because it’s already cracking open the seal on my creative door.

Love what you are saying. One aspect of the sinatra complex is that it is pretty true for cultural leadership in the US and internationally…what I mean by that is, people look to New York. The cultural budget here is bigger than the NEA.

So, in terms of performing for audience, the concept works fine to go elsewhere. In terms of moving the cultural tide of the country or the world, New York is the clear front runner on that side of arts advocacy and funding and governmental involvement.

Unfortunately, in Europe they are pointing to us and saying it is working to be less supportive of the arts…when we know its not working for all the reasons you site. Then vice versa, other cities have almost no cultural budget, and there are many who resist an increase in arts funding in NYC because of that.

So, dynamic cultural leadership in New York, is incredibly important in the scheme of things, and is not going to come out of anywhere else here in this country. There is no where else that can interact directly with wall street and real estate issues that are invading everywhere else. It’s the head of the hydra. And I think arts and culture have to play an important role in beheading the hydra.

So, that plays into the cycle you lay out as well, because of the concentration of the best arts leaders, who are often rewarding to work for, the best artists flock here. It’s not just about audiences, its about who you can work with as well.

What you say is definitely true — NYC is still the “cultural capitol” of the US, and very influential, and consequently much of the writing that occurs focuses on NYC. This is unfortunate, in my opinion, because the economic environment in NYC is so harsh that it pushes the arts to be ever more conservative. That said, I also think that the regional theatre movement was (initially, at least) focused on decentralization — a realization that we should not be a country with a centralized arts capitol.

While I do care about the larger national and international conversation about the arts, my focus in this blog is on releasing the individual to live a creative life, rather than participating in the American Idol-like arts hierarchy. I want to see artists have a chance to create, and people in all areas of the US have access to the arts. So NYC is not a focus for me at the moment, as important as it currently and historically is.

Bravo.