My curiosity was aroused by this sentence:

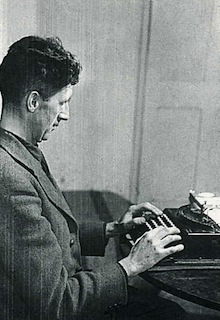

His manual typewriter — rather suitably, in the light of his faint anarchist leanings — was later bestowed by Sonia on the 1960s hippy-radical news-sheet, the International Times. — D.J. Taylor, Orwell: The Life

Why did George Orwell’s widow give the typewriter to the paper? And where was it now?

Orwell had died a sad lingering death from tuberculosis in 1950. His life had been bare in comforts, as severe as the gaunt look of him — rail thin at 6-foot-3, almost cadaverous, his face a mask of sunken eyes and cheeks. He wasn’t the sort to have partied with the pot-smoking crew of free-wheeling anarchists who produced the paper, however serious their anti-establishment ideology.

What, in fact, was the connection between the author of two of the most famous and important books of the 1940s — Animal Farm and 1984 — and the scruffy underground London weekly that began publishing more than a decade after his death?

The current editor of IT: International Times, The Newspaper of Resistance, Heathcote Williams, didn’t know. The typewriter episode was news to him. “What a fascinating tidbit,” he said in an email. “I’d love to know the truth (maybe IT can pretend that we’ve found it and then sell it to the University of Texas to raise funds for the paper — a passing criminal thought!)”

If anybody knew, it would be two of the founders of the paper, Jim Haynes and Barry Miles, he said, and he gave me their contact info.

I messaged Haynes, who wrote back:

I knew Sonia very well and lived in her basement apartment in London for one year in 1965. She gave me the typewriter and I loaned it to Tom McGrath, who Jack Moore and I invited to be the first Editor of ‘I.T.’ Tom had one major bad habit: heroin. I suspect he later sold the typewriter to feed his heroin habit. I never got it back even though I asked him about it a number of times over the years. Tom later died without my ever finding what happened to the typewriter. I am not even sure if Tom knew where the typewriter came from.

Miles, it turned out, had mentioned the typewriter in his book London Calling: A Countercultural History of London Since 1945. I messaged Miles to ask if it was the one that Haynes had given to McGrath.

“Yes, it was the Orwell typewriter that Tom scarpered with,” he said in an email. “We didn’t hear from him for six months, then it turned out that he’d returned to Scotland. I’m sure the typewriter was sold to get money for heroin. Impossible to trace. I wish I had a picture of that typewriter. I have a vague memory of it being a portable, though a pretty large one, but that’s all.”

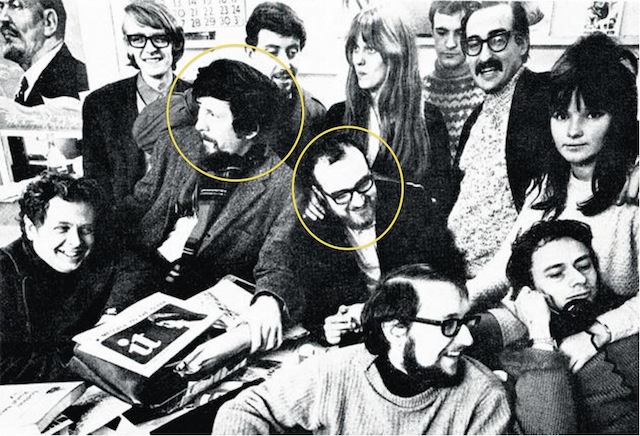

Adam Ritchie took this photo of the IT office in the basement of the Indica Bookshop in 1967. It shows (left to right): Jeff Nuttall (deceased); Miles; Jim Haynes (circled); Peter Stansill; Tom McGrath (deceased, circled); Sue Miles (deceased); Jack Henry Moore (deceased); Roger Whelen, David Z. Mairowitz, John “Hoppy” Hopkins (deceased) and Christine Uren, (Miles’s assistant). Not shown is Michael Henshaw, IT’s accountant (deceased).

I sent Miles a photo that showed Orwell typing on his manual portable Remington. “Well, it looks extremely like the one I remember,” Miles replied. “Can’t guarantee it. We should have sold it to an institution where it would have been preserved and used the money to buy two typewriters for IT. Goddam!”

For further confirmation, I sent Haynes the photo. “Yes,” he replied. “I think this was the typewriter. Tom moved to Glasgow and then later to Edinburgh. I saw him fairly often before he died and I always asked about the typewriter. He always laughed and said he did not know what I was talking about. I never told Sonia Orwell whom I also continued to see until she died.”

Why did she give Haynes the typewriter? Apparently for the simple reason that she believed in his many projects. “I once walked into a restaurant in Paris and saw her sitting with a table full of French intellectuals,” he recounted. “She called me over, introduced me to everyone, said that I had changed Britain for the better when I lived in Edinburgh and London and that I would probably do the same in France. She was super nice.”

As he has written elsewhere, she was so nice that all she had charged him in rent for the basement flat in London was “the princely sum of serving drinks at her many cocktail parties.”

I could stop here. I had the answers to my questions. But that would be a disservice to McGrath, who was no mere heroin addict, and it would not do justice to the grandeur of Haynes’s career.

When McGrath was invited to be the editor of IT he had already been the editor of Peace News, the weekly paper of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, CND, which had been founded in 1936 as a radical pacifist journal and in subsequent decades had taken up other antiwar and human rights causes.

McGrath was, furthermore, a poet. He had appeared in the seminal Royal Albert Hall poetry reading, in 1965 (the idea for which had originated at a London bookstore where, not incidentally, Miles had been one of the managers). And he was not only a poet. He was an extraordinarily accomplished polymath — jazz pianist, playwright, arts activist, and theater founder. Having kicked his habit on his return to Scotland, he became, as described in the Scotsman, a “prime mover in the growing Scottish cultural revival of the 1970s.”

And what, for example, were the projects Haynes was involved in that gave Sonia Orwell her confidence in him? Well, here’s the short list:

+ With Bill Levy, he founded SUCK, an English-language underground newspaper based in Amsterdam that promoted sexual freedom and was the first of its kind in Europe.

+ He opened an avant-garde bookstore, The Paperback Bookshop, in Edinburgh, and helped start a theater company, The Traverse Theatre Club, which produced Heathcote Williams’s play “The Local Stigmatic” on the recommendation of Harold Pinter, and, when the company moved to London, produced Joe Orton’s “Loot,” which subsequently transferred to the West End and won the Evening Standard’s Best Play of the Year Award.

+ He organized (with Sonia Orwell and the publisher John Calder) the first International Writers’ Conference at the Edinburgh Festival, in 1962, attended by more than 70 writers (including the American writers Henry Miller, Norman Mailer, William Burroughs, and Mary McCarthy; the British writers Lawrence Durrell, Angus Wilson, Alexander Trocchi, Hugh MacDiarmid, Muriel Spark, Edwin Morgan, and Stephen Spender; the Austrian writer Erich Fried, and the Indian writer Khushwant Singh).

It’s worth noting that after Sonia Orwell’s death, in 1980, Haynes wrote an autobiography, Thanks for Coming! (published by Faber & Faber). Among his many other books, he has a new one, Trips and/or How I Came to Dine with Vladimir Putin, to be published this year.

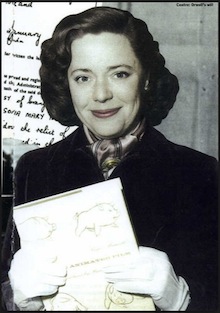

As to Sonia Orwell, she had a hugely controversial reputation. I showed Haynes what D.J. Taylor had written about her in his biography and asked him to assess it. The gist was that her enemies accused her of being an unfaithful gold digger who married the much older Orwell on his deathbed to gain control of his literary estate and the wealth that was beginning to pour in from his writings, while her friends vigorously pointed out that she was not only a great comfort to Orwell, who valued her enormously in the time he had left, but that after he died she was a diligent guardian of his interests, lending an enormous boost to his literary reputation particularly in co-editing with Ian Angus the four-volume Collected Journalism, Letters and Essays, which cemented Orwell’s standing as one of the greatest essayists in the English language. Moreover, she died penniless, believing that she’d been cheated by the longtime accountant for the Orwell estate. (According to Taylor, it was his inept investments that lost the money.)

“There is no doubt that Sonia was an extremely difficult woman,” Haynes messaged. “I happened to like her and found her delightful in every way.

But she could be extremely difficult. Definitely an intellectual snob in many ways. Her command of the French language was almost perfect and she could not understand why everyone could not speak it as well. She guarded Orwell’s literary output and considered it her duty to protect it. She was cheated by Orwell’s literary agent. She lived modestly. She was probably an alcoholic and drank a vast amount of red wine.

Should anyone care that Orwell’s typewriter went missing? Though I haven’t asked them, I’m sure Miles and Haynes both forgave McGrath long ago. I’d even doubt that they felt there was ever anything to forgive in the first place. Besides, where are anybody’s manual typewriters now?

Postscript: A note about the origin of IT is in order. Miles messages that John “Hoppy” Hopkins and he came up with the idea for the newspaper. Easter, 1966, they put out a trial-run edition. “It was Hoppy who actually asked Tom to come to London” to be editor, he says. “A telegram to Tom, who was staying in Adrian Mitchell’s cottage in Wales, simply read ‘Call Hoppy’. Tom had recently resigned from Peace News. Hoppy had been one of their regular photographers, as well as a CND activist. Hoppy and I knew Jim because I had met Jim in Edinburgh in 1964 and stayed in touch. Jim insisted that if he came, Jack Henry Moore had to be made a member of the editorial board as well. We very much wanted Jim on board, so we got Jack as well.” Miles adds that “none of this matters,” but I include it here for the record.

PPS: For anyone interested in the history of IT, which has outlived all other alt-press papers of the 1960s, Jim Haynes clarifies further:

Originally I wanted to start an underground newspaper in Edinburgh and even raised money while I was living in Scotland. When I moved to London, I gave the money back to friends in Edinburgh. I later raised the money to start ‘I.T.’ from an American friend in Paris, Victor Herbert, who refused to loan it to start the paper, but loaned it to me personally. Later when I attempted to repay him, he refused and said he was proud to have helped launch the paper. I am pretty sure he was never repaid. Miles and Hoppy and Jack and I combined our desires to create a newspaper and we were successful from the start. Miles and Hoppy think ‘I.T.’ was their idea; Jack and I think it was our idea. In fact, we four created the newspaper. Hoppy knew Tom McGrath. Jack and I also were friends of Tom’s. Jack stayed with him when he traveled to London before Tom moved to Wales. Tom was often a customer of my bookshop, The Paperback.

Crossposted at IT: International Times, The Newspaper of Resistance.

“Ka-ching” — certainly the sound of discovering a sleeping film script gem — but also the sound of the finish of a manual typewriter carriage’s run.

I hear that McGrath sold the machine in question to David Cronenberg who, after subjecting it to nefarious experiments in biomorphic typing, gave it new life as the “bugwriter” that appeared in his film of Naked Lunch. Currently it’s crawling around an empty movie studio leaving a trail of random letters…

<<>>

You mean you never kept one, Jan? My manual typewriter is right next to me – I use it to calm down.

..

btw:: it is highly unlikely that that Remington was the only machine Orwell ever had – writers, especially word-churners like Orwell, used to get through more than one at least – they do lose their touch and that Remington model was real bugger when the ribbon devices got worn…. Burroughs is seen with several kinds – and indeed sold several to feed his habit too …. Mcgrath probably sold it as much to feed the habit as to get rid of a machine that was a pain to use.

Now that you mention it, Jim, I realize I still have my old Olivetti portable stuck in a closet somewhere along with other useless paraphernalia (an ancient Canon 16mm newreel camera, for instance). It was relatively lightweight and served me well for years, but the truth is it was one helluva pain when it came to keeping the ribbon wound right. Maybe all portables had ribbon problems?

not all portables – some Olivettis did.. the Linea 44 was best of them though the market was saturated with 32s – but don’t get me going, Jan.

It’s interesting how an author’s typewriter gets fetishised … like the old oak desks of earlier generations .. as if the hardware may contain echos of the writer’s pen or keystrokes and all it may need is the caress of a shaman’s hand, some soft rub of the space bar or the leather desktop, to invoke a poltergeist who’ll clatter out lost lines and never quite finished stories. Instead , we only ever hear the the hammer of the auctioneer …

well put, monsieur. the fetishizing bizness brings to mind this recent story:

Why Nobody Wants Saul Bellow’s Desk

http://www.wsj.com/articles/why-nobody-wants-saul-bellows-desk-1458753780

i wouldn’t want it either, even if it was being advertised for a buck instedda ten grand.

now have a look at this almost lost objet d’art:

Orwell’s Typewriter, Meet Wold’s Bar Stool

http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/2016/03/orwells-typewriter-meet-wolds-bar-stool.html

With regards to the whole fetish question, it seems to harken back to some non-pagan carryover from the supreme act of fetish – the laying down of hands in the Christian faith – from Christ to the Man in the Vatican.

Personally, I don’t buy the Tom McGrath-sold-the-Remington thesis. Maybe all of the other pretendants can claim to have started IT, but no one can dispute that I made the first ten issues happen on a day-to-day basis as assistant editor, taking it to the printer, etc. I never even heard of Orwell’s typewriter and it certainly was never in the IT offices when I arrived before issue one. I would have to have known about it, and certainly Tom would have shared the information with me. It’s a great story, but I’m afraid it might turn out to have a simpler, banaler explanation: in those days, things (valuable and otherwise) just vanished from the editorial office. It was all part of the game.

David Mairowitz

The tale of IT gets more and more amazing — and convoluted. Thanks so much for your input. Peter Stansill just sent me, separately, his blow-by-blow account of IT’s history, a shorter version of which he tells me was published in the British Journalism Review, in Dec ’06. He says “the typewriter story should definitely be a movie, sort of like ‘The Red Violin.'”

Somebody oughta publish an anthology of IT tales, or has that already been done?

btw, Peter Stansill says, in an email: “I remember this typewriter well, as it was the only one in the IT office downstairs at Indica, where that photo was taken. I used it many times in my original capacity of Operations Manager …”

Not tales, but there is my book “Some of IT” if you’re lucky enough to find it anywhere.

DZM

ah, thanks. you’re right. even references to it via a few notable book sites don’t show it. but according to this:

https://www.worldcat.org/title/some-of-it/oclc/6903751&referer=brief_results

the book is held by The British Library and 25 university libraries worldwide. i’m surprised that the vaunted NY Public Library, which, in its research division, is supposed to have e-v-e-r-y-t-h-i-n-g, doesn’t have it. it doesn’t have Miles’s “London Calling: A Countercultural History of London since 1945,” either, though that’s easily available. weird.

IT published the Mairowitz-edited ‘Some of IT’ in 1969 for £1 and it immediately sold out. It had a silvery Melanex wrap-around cover with a sticker bearing the IT logo. The original edition now sells for hundreds of pounds on rare book sites. One contributor copy I signed for Alex Trocchi went for £400 about 20 years ago. All I have is a copy of the pirate edition, which some hip entrepreneur printed several years later. Well, I guess we were all outlaws, stealing from each other.