LATEST UPDATE: Sept. 1 — “Killing Kit” is to be staged in a London try out. The production opens at The Cockpit on Sept. 21.

FURTHER UPDATE: Feb. 15 — The reading came off well, I’m told. Somebody in The Cockpit audience tweeted: “Beautiful, meaty, dangerous Elizabethan play for today’s Elizabethans. Real writing. Great night.” I’ve heard that Mike Figgis did some filming, and he’s cooking up a video. Am awaiting further word.

UPDATE BELOW: Jan. 10 — “Killing Kit” will get a “first rehearsed reading” next month, on Feb. 12, in London at The Cockpit.

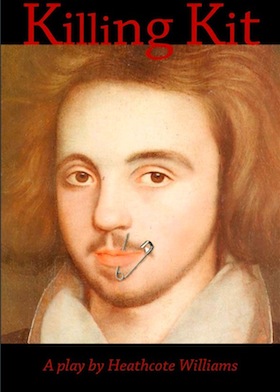

Heathcote Williams’s play-in-progress, “Killing Kit,” has yet to beIn a detailed preface to the play, Williams notes that “Marlowe has been called ‘the most notorious early modern ‘bad boy; and ‘a cross between Oscar Wilde and Jack the Ripper.'” Believed to have been the same age as Shakespeare, but not at all like him, he was “an anarchist atheist and a subversive blasphemer, murdered at the age of 29 at the request of one of a number of persons not unknown.”

“Marlowe was a force of nature,” Williams writes. “He catches the imagination like almost no one else.” The preface summarizes relevant particulars about the Elizabethan period as “a kind of vade mecum for the actors,” he says. “It’s a quick way of putting them in the picture.” And us.

From the Preface:

The reign of Queen Elizabeth the First saw the beginning of the British Empire, an Empire that was to morph into the American Empire, and her reign would see the creation of the cultural norms that have governed both of these two imperial powers – forces that have dominated the Western world and its landmass for centuries.

The period also saw the inception of a National Security State designed to see that this Elizabethan proto-Empire survived by its destroying any opposition: an understandable opposition to its intractable hierarchies; to its rigid class barriers; and its doctrinaire interpretation of a state religion – all of which were used to justify Elizabethan society’s unforgiving structures which stood in the way of social mobility. To serve the status quo and the beginnings imperial power (spawned by piracy), Elizabethan citizens were overawed and controlled by a kind of magical thinking about their monarchy which excused its excesses.

Henry VIII reputedly killed some 72,000 of his own people, and his daughter Elizabeth was cast in similar mould: the Elizabethan form of government was arbitrary, theocratic and draconian and it depended unashamedly for its enforcement on propaganda, torture and mass execution. Some thirty people a week were publicly executed in Elizabethan London, and the Royal Rackmaster, Richard Topcliffe, was in regular personal contact with the Queen, who is recorded as having taken a morbid interest in jointly devising new contraptions for Topcliffe’s torture-chamber in the Tower of London.

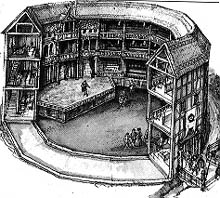

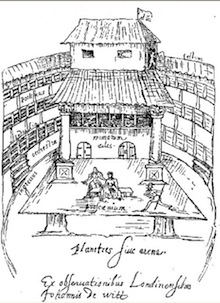

By contrast, the age was also to see the first green shoots of an age of reason and scientific enlightenment whose insights and aspirations were most radically brought to life by its contemporary playwrights. One in three adults in London would see a play a night, and it’s through the playwrights’ lens that the Elizabethan world can be most vividly glimpsed.The Globe and the Rose in Southwark regularly had queues of 2000 people eager to attend, and by the late 1580s there were some 400 plays in repertoire in the courtyards of London’s Inns and in the custom-built theatres that were quickly springing up.

The very first of these writers to challenge the prevailing culture were those written by Christopher Marlowe, described by the Victorian poet Swinburne, as Shakespeare’s John the Baptist. Marlowe was instinctively transgressive, but it was his membership of Sir Walter Raleigh’s School of Night (also known as the School of Atheists) that helped to give Marlowe a revolutionary perspective on the Elizabethan mindset.Artists, adventurers and scientists were members of The School of Night. The School could at once play host to Giordano Bruno, who was challenging the Church’s view of the universe, and to an Algonquian Indian Chief from England’s first American colony, who was regarded in London upon his arrival with great suspicion as an infidel.

Raleigh’s School of Night was attended, for example, by the discoverer of Jupiter’s moons, and by pioneers of algebra, optics and mathematics; by builders of nautical instruments; by engineers and by poets.

Its aims, however, were predictably regarded by the Elizabethan state as heretical. […] Sir Walter Raleigh’s School, described by Professor Frances Yates as a Pythagorean Hermetic circle […] would provide a way for its youngest recruit, Christopher Marlowe, still in his early twenties, to see the Elizabethan world through radically different and more exotic eyes. The School of Night inspired the metaphors of astronomy in Marlowe’s plays, and just as Thomas Harriot’s active quest for hidden knowledge would have a bearing on the creation of Marlowe’s devotee of magic, “Dr Faustus,” so too Raleigh’s buccaneering character would serve to nourish Marlowe’s two-part play, “Tamburlaine the Great.”

But since freethinking spelled subversion, and since atheism counted as seditious heresy and, at the time, would constitute a capital offence, the School of Night was closely watched by Elizabeth’s secret service, her ‘intelligencers.’ From the point of view of the Elizabethan Establishment what was being discussed there was tantamount to terrorism and as, in both Marlowe’s plays and in the surviving transcripts of his recorded statements, Marlowe bubbled over with insurrectionist views, Marlowe himself would also be kept under surveillance, notwithstanding his own earlier involvement with the secret service while still at Cambridge.

Marlowe’s surveillance was undertaken for obvious reasons: he fearlessly castigated England’s war economy and the theocracy which sought to justify it. He favoured science instead of superstition; he was anarchic rather than deferential; he risked both life and liberty to satirize the tyranny and corruption which he saw as dominant; he tore into Catholics and Puritans alike and defied the hierarchical, and monarchical superstitions of the day.

All of that is traced in play, which also lays out Marlowe’s huge literary significance as a writer. “Marlowe’s major innovation was the sonorous, actor-friendly blank verse line that he bequeathed to Shakespeare and Milton,” the preface notes. “Shakespeare would make free use of what Ben Jonson called ‘Marlowe’s mighty line,’ and Marlowe’s invention became Shakespeare’s most invaluable template. He seized upon it as a refreshing departure from the stilted versification that had gone before.” But as Williams imagines him, Marlowe is less than pleased by what he considered the plagiarism of a rival playwright. Worse, it galls him that Shakespeare accepts the status quo, glorifying the concept of royalty both in his plays and his life. See this:

Scene Twenty. The Rose. (Henslowe is Philip Henslowe, impressario of The Rose theater. Kyd is the playwright Thomas Kyd, a contemporary of Marlowe’s and Shakespeare’s.)

(Kit is engaging Thomas Kyd in conversation.)

KIT: It’s a commission, Tom. From an elusive Lucifer.

KYD: I know full well who it is, Kit. He’s the model for your Faustus. Raleigh’s School of Night, where Raleigh sells his soul for knowledge and power. It is Faustus’ alchemical den.

KIT: My lips are sealed…

HENSLOWE: (coming over; boisterously) Now let me interrupt you schemers. (He indicates a figure in the distance as Thomas Kyd leaves). Have you two met each other, Kit? I forget. But I believe not and of course, you should, you should. I realize you’ve both been ploughing parallel furrows.

KIT: (turns to see who Henslowe is referring to. He glances at the figure of Shakespeare) You could say we’ve met. (Silence) You could say our paths have crossed. (Silence) Rather fruitfully for Master William. No? (Silence) Forever mousing out something from one furrow, and fetching it to another. Nearer to home.

HENSLOWE: (awkwardly) Oh?

KIT: “Who ever loved, that loved not at first sight.” I wrote that in Hero and Leander. Remember? Master William copies it. Filches it for his own profit.

(The figure of William Shakespeare, much like his Stratford portrait, stands at the edge of the rehearsal room, now looking uncomfortable.)

KIT: But you can’t wrong me Master William. There’s always more where that came from. Do I have need to steal from you? (shrugs) So, feel free to steal – Thief of Baghdad-upon-Avon. (laughs) Milk-white Warwickshire swan: so quiet on the surface, so busy pilfering underneath.

HENSLOWE: (an embarrassed frown) How so?

KIT: How so, Henslowe?! (suddenly inflamed, and launching into a possessed tirade) How so? His Richard II is my Edward II! My Jew of Malta is reworked into his Merchant of Venice (where he steals my line about the moon sleeping with Endymion). How so? here’s my double-dyed villain Barabas, in the Jew of Malta, “As for myself, I go abroad at nights, and kill sick people groaning under walls, sometimes I go about and poison wells…” and then, then what? what a surprise, we have his Shylock! (he points vigorously) And then? then what? His Richard III is also spawned by my Barabas, who drinks what? poppy and mandrake juice so then, lo and behold, my new invention of poppy and mandrake juice is not yet exhausted and drunk dry but it’s obliged to be served up again for his Othello. His Aaron, in his Titus Andronicus, remember? (Henslowe nods,beginning to look a little alarmed) His Aaron only breathes because of my Barabas. His Henry VI is lifted from my Tamburlaine (so that by rights we should have had both our names upon the playbills). (Henslowe twitches) His Anthony and Cleopatra rests upon my Dido, Queen of Carthage, without which his Romeo and Juliet couldn’t exist either. My Dido’s Nurse is become his Juliet’s Nurse, and his Prospero? His Prospero is the mirror image of my magician, Dr. Faustus. Who denies it? Not him. Eager for my visions of ecstasy in his Midsummer-Night’s Dream Master William has someone “wound Achilles in the heel and then return to Helen for a kiss.” A kiss that he’s stolen from my Faustus.

So, Henslowe, if you want to know what makes William your new genius, then do what he’s been doing: make yourself cross-eyed by squinting at Kit Marlowe. And then scribble it all down while you surreptitiously slink around at the back of house, lurking behind a pillar (Shakespeare cringes, then looks away.) But look, he’s not looking at me now, is he? no, your long-necked, preening, peering swan. (Kit gives a tortured laugh of disdain, as Shakespeare looks increasingly furious.)

“Is this the face that launched a thousand ships?” (to Henslowe, and then looking round the auditorium for support) Has anyone yet caught that line reappearing in his Troilus and Cressida?

ROSE ACTOR ONE: (shouting out) Yes! “Helen is a pearl whose price hath launched above a thousand ships.”

ROSE ACTOR TWO: (laughing and jeering): Act two, scene two!

KIT: (indicating Shakespeare) Oh, look at how he shrinks from me. He’s ashamed of being found out, so he hates me! Proprium humani ingenii est odisse quem laeseris. It’s human nature to hate a person whom you have wronged.(Kit points at his own face and then shouts out, angrily) Look sneak thief! Is this the face that’s launched a thousand Shakespeare lines? (he stabs his finger angrily at Shakespeare) And is that the face that holds the tongue that can only become articulate by imitating me?

Look at him, Henslowe! Oh, how he longs to swim on the tide that carries me out, and look how he’s now using his Richard III to do so. (outraged) Tamburlaine’s “dreaming prophecies” become Richard III’s “prophecies and dreams;” and Tamburlaine’s “sweet fruition of an earthly crown” becomes “How sweet a thing it is to wear a crown” in his Henry VI. “All the wealthy kingdoms I subdued” in Tamburlaine, surfaces again in Henry VI as “all the wealthy kingdoms of the west.” Making Dido’s anchor of crystal rocks? – that he steals for Cleopatra’s barge, and on and on and on, and on, Henslowe! All mine! The petty Stratford pirate is drenched in Marlowe’s gold dubloons – he can’t resist my blank verse forms – ti-tum-ti-tum-ti-tum-ti-tum ti-tum – my pentametric prosody; my lines swallowed whole by his scavenging beak and then shat out underwater! “Holla, ye pampered jades of Asia.” Watch him take that line from Tamburlaine, and then give it to Falstaff’s swaggering sidekick, Ancient Pistol, who gets it wrong.

He steals my soliloquies. He cribs my five beat lines: (with exaggerated emphasis on the beats) ‘I’m say-ing noth-ing now, I must be si-lent.’ He’d even steal my silences, if he could. He steals so much of me, Henslowe, people will think he’s me.

It’s not just me, Henslowe – the playmaker Robert Greene can’t forget your precious paragon’s plagiarisms either. (He turns towards Shakespeare.) You’ve seen Robert’s pamphlet? (Shakespeare makes no response.) He calls you “an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers.” And why? Because you stole Tom Kyd’s Hamlet! “Nay more,” Robert accuses you, “Nay more, that man so eclipsed Thomas Kyd’s fame, purloined Thomas Kyd’s plumes, can he deny the same?”

(darkly) Look, glove-maker’s son from Stratford – come to steal our gloves! – Well, now slip your skinny thieving fingers out of them. (He indicates Shakespeare’s blushing with a snort of derision.)

ACTOR THREE: (shouting from the wings) Your fingers work his gloves, Kit! You tell him!

KIT: (laughs, then moves closer) Rose-cheeked, eh? Just as the beautiful youth in my Hero and Leander, is “rose-cheeked,” then, lo, so is he ‘rose-cheeked’ again in your Adonis – in your Venus and Adonis – your Adonis suddenly has to be ‘rose-cheeked’! (He points again.) So blush William! Remember my Leander? “Some swore he was a maid in man’s attire, for in his looks were all that man desire”? So my Leander arouses you, and so you want him and so you steal his rouge for your enfeebled, simpering version of Leander, your effete Adonis, and who’s rose-cheeked now? Blush again, Shagsper!

Go back home, you Stratford tuft-hunter. You royalty-mongering minion for the House of Tudor – upholding the rights of princes and all of the pomp and circumstance of rank. Go back to your grand house in Stratford and to your lavish parish tithes and to your vainglorious coat of arms, worshipful master William. Royal suck-arse. (turning to Henslowe) Remember my Machiavellian Mortimer who scorns the world? Who bids his Queen farewell and then goes to die “as a traveler goes to discover countries yet unknown.”? Remember him? (Henslowe nods, reluctantly, as Kit points at Shakespeare.) Guess what? Enter centre stage Shagsper’s spoiled moaning, whingeing, inactive Hamlet, soliloquizing on death. And what does Hamlet say? What does Hamlet contemplate, Henslowe? Why, of course: “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns.” Could The Lord Shagsper secretly be wishing me there with his not so secret and his blatant thieving – is your coming man secretly wishing me dead? `Stripped bare and my soul shipwrecked? Would you have me dead, Shagsper?

Steal from Lucretius, all you like, and from Plutarch, and from Chaucer, and from Hollinshead, their mouths are full of earth… they’re dead! But when it comes to me, you steal the very food from my stomach, and the drink from my lips!

HENSLOWE: . . .Kit!

KIT: (Kit turns on his heel.) ‘What flies, I follow. What follows me I shun’.

Shakespeare stares at Kit. He’s livid, but says nothing. He leaves.

HENSLOWE: Kit, Kit, forget your stalkers . . . Now, Thomas Kyd is grateful to you too, I’m sure, but – a word to the wise – I do know that Thomas also berates your rashness in your constantly attempting sudden privy injuries to men. Please do forget and forgive, Kit. So you’ve had a magpie who’s clipped your coinage – (shrugs) So, he’s picked up a few of your trifles. Let it go . . .

KIT: (points furiously to where Shakespeare has been standing) Forget? Did not my conjuring raise him?

HENSLOWE: Up to a point, but listen . . .

KIT: I’m to have my identity absorbed? By the Queen’s Men? By craven, timeserving players wearing the royal robes? The Royal livery? (he spits) Royalty-mongering lickspittles, hungry for tinsel baubles from a Tudor tyrant’s throne?

HENSLOWE: Listen . . .

KIT: (still remonstrating) I’ve been the spark that lit his fuse and now he wants the whole of the night sky to himself?! How does Greene characterize him, Henslowe? as a monstrous crow with a tiger’s heart who both robs and devours his rivals.

HENSLOWE: Kit, Kit, Greene’s envious railings against our much-prized Will (who begins to be making us a little fortune, by the way) are no more than the peevish carpings of a weak and malignant spirit. You mustn’t copy that creature whom, as you know, dubbed himself with facetious pride as the “only Shake-scene in the country.” Even less reason to copy him now since he’s dead.

KIT: (whipping round) Dead?

HENSLOWE: He died Sunday last of a surfeit of pickled herrings; too much Rhenish, and too much guilt, I dare say, at allowing his piteous wife Em to be pimped by a vile thug called Cutting Ball in this very theatre, all to keep the vicious little ogre in victuals.

KIT: Poor Robert.

HENSLOWE: I saw his lice-ridden body. Overgrown with a sluttish white mould. He’d made a bay-leaf crown for himself before dying.

Poor? Poor? He was exceedingly rich in insults and in insufferable odiousness. He cursed you for “daring God out of heaven with that atheist Tamburlaine”; and he cursed you for your “impious instances of intolerable poetry”, and he cursed me for everything else. To Greene, Kit, you were just a “mad scoffing poet bred of Merlin’s race” – as he never ceased to tell us. Forget Greene, Kit. Remember the magnanimous Petowe instead who says that “Marlowe’s honey-flowing vein, no English writers can as yet attain.” (Kit is placated.) And be aware that your Stratford rival is well aware of you, Kit. He acknowledges your power in a sonnet, as “a spirit, by spirits taught to write, above a mortal pitch”. How’s that?! But listen (sternly), I can’t impress upon you enough that I’ve no wish for him to be dethroned. Share the throne instead, Kit. (Kit looks momentarily mortified)

I want my theatre to be full of Kings, Kit! Spilling over with Kings and Queens in crimson taffeta breeches and sensational, rustling skirts. Gilded with Olympian glory, and myriads of pearls. None quarrelling. All amicable. All living forever in verse, and all having their lives enhanced by it. Remember your Ovid? “Verse is immortal, and shall ne’er decay”? So, please, please be agreeable. We are short of rich patrons. The plague has seen to it that all my former goldfinches have fled to the woods.

Now, to business, we’re re-staging Faustus, Kit. Twenty thousand people have come to see it . . . Nothing fills the theatre as well as Faustus, with your mighty lines. Not forgetting your leaping incendiary devils. Your baiting of corrupt Cardinals! Your odours of sulphur and brimstone; your trumpets and drums! Your conquering swords! ‘Not marching now in fields of Trasimene’ . . . (embracing and appeasing Kit) Your mighty lines from such a torrential clutch of mighty plays, dear Kit. Dear kind Kit (he puts his arm around Kit). This year is proving a banner year for you, no? Nothing must spoil it. Beware your own King Edward. “Base fortune, now I see that in your wheel, there’s a point to which, when men aspire, they tumble headlong down.”

Henslowe looks around anxiously for Ned Alleyn and then beckons him over.

HENSLOWE: (calling out enthusiastically) Ned! We’re to have another season of Faustus. Run that speech past me again. I want to see Faustus suffer much, much more as he’s wrenched away from all the transient joys of the world. Remember? One more rehearsal if you don’t mind. Faustus in anguish, yes? More anguish.

NED/FAUSTUS: (steps forward and closes his eyes to refresh his memory) O Faustus, now you have but one bare hour to live, and then you must be damned perpetually! Stand still, you ever-moving spheres of heaven that time may cease and midnight never come . . . Let this hour be but a year, a month, a week, a natural day, that Faustus may repent and save his soul! The stars move still, time runs, the clock will strike, the devil will come, and Faustus must be damned. O, I’ll leap up to heaven!– Who pulls me down? – See, where Christ’s blood streams in the firmament! One drop of blood will save me: O my Christ! — my Christ! My Christ!

HENSLOWE: (whispering to Kit) Ned wears a crucifix now, you know. Did you notice? Last time he performed Faustus he said he counted one more devil on the stage in the damnation scene than were really there in the cast! Did you know that? He may have gone mad, Kit. We live in mad times. Quite mad. The Armada has unbalanced everyone, even though England won. Not just Ned and his apparitions … England may have become distracted. People now think of the plague as an occult Armada; a fearsome avenging; an ubiquitous miasma; fevered puritans see armadas of prostitutes invading every street and they pick upon innocent women to scourge naked in front of the Bridewell. Horrors, Kit. Horrors. Hell on earth. (calling out to Alleyn) Wondrous, Ned. Wondrous.

By the way Kit, I understand. I do understand. I noticed. You know, you omitted to mention that young Will steals from all three of your plays – Tamburlaine, Edward II and Dr Faustus – in his Taming of the Shrew. It shows great forbearance on your part not to have pointed that out too. How does it happen, Kit? Well, you know yourself, playbooks lie about the place, and then what? passing jackdaws pick them up. Before the lot of them are bequeathed to the privy. You mustn’t be distressed. By the way, the general view is that he bases his Mercutio character on you too – in his Romeo and Juliet – and I have to tell you that he does catch you well there, Kit. Impulsive; passionate; volatile. You’ll have to admire it when you see it. You’d have to. Have to. But you’re still you, Kit! Your currency’s still valid!

(Silence.)

KIT: (darkly) Maybe. (pause) But there’s still someone who wants the stage all to themselves. And they betray themselves.(pause) My tide rises, and yet I feel a fatal undertow drawing me down. Why?

Seems to me the role of Kit could make a young actor’s career.

POSTSCRIPT: Jan. 10 — “Killing Kit” will get a “first rehearsed reading” next month, on Feb. 12, in London at The Cockpit: