foot in mouth: April 2011 Archives

(Note: Somehow a couple of paragraphs got disappeared last night--not erased but buried in computer code and thus invisible. I've put asterisks by them, newly restored...]

Late February and March were chock-a-block with venerated masters of modern dance, from graying to old to dead. The plethora of offerings forced us to think again about what we will be left with in their wake.

Principally, Cunningham did, whose troupe had its fourth to last hometown show. In the oldest dance on offer, Antic Meet, from 1956, the view is even farther back, as the choreographer looks to his scrappy youth. Here's the start of my Financial Times review:

The first of this irreplaceable company's New York appearances in a final, globe-trotting year moves backwards in time.The Joyce programme ends with 1958's Antic Meet, in which Cunningham reconfigures his beginnings in vaudeville - before he encountered modern dance or even graduated from high school - through the prism of absurdist theatre.

Long-time collaborator Robert Rauschenberg dreamt up the inspired Dada props and costumes for skits loosely based on hoofers, musclemen, tumblers and clowns. Cunningham himself came up with the most famous prop: a café chair strapped to his back that he uses to support a dotty ballerina. She makes a dramatic entrance through a door she has provided for herself.

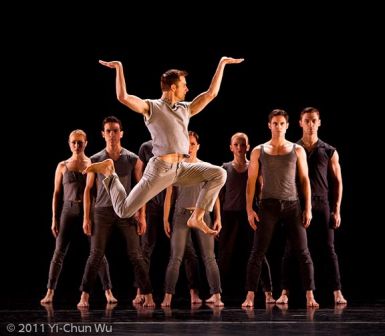

Marcie Munnerlyn and Rashaun Mitchell. Photo by Yi-Chun Wu.

Antic Meet operates by the clown laws of the universe: if you put one foot in front of the other, you will trip; simple acts grow impossibly tangled; the harder you try, the less there is to show for it; nothing follows from anything. Though the opening-night cast lacked sufficient antic energy, the performance still managed to suggest a new back story for the sudden shifts--in tempo, direction, everything--that distinguish a Cunningham dance.

Fast-forward to 1982, when arthritis riddled the choreographer's hips and feet. Quartet is a quintet, with him as the nearly stationary fifth wheel.....

Quartet. Photo back to front: Robert Swinston, Krista Nelson, Jennifer Goggins, Brandon Collwes. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

For the most desolate Cunningham dance, and the first of the computer dances, click here.

The Cunningham company is going the way of Balanchine minus the New York City Ballet. It has a trust, which will send out rehearsal coaches (repetiteurs, ballet deliciously calls them) among former company members to interested and able troupes and college departments.

But who will be able?

Cunningham technique is at least as specific in its demands as that of Balanchine--and yet much less widespread. Even with Balanchine, troupes as venerable and reliably excellent as the Mariinsky/Kirov haven't always been able to pull the ballets off. The emphasis can be just off enough that you cannot make sense of what you're seeing. (To be fair, I've only witnessed one Mariinsky Balanchine to suffer that fate: the ballsy, athletic Rubies.)

Last month, I witnessed two cases--one positive, the other, not so much--of what the Cunningham rep might have in store. The positive was Trisha Brown company member Neal Beasley doing a solo that only its author, Brown, has performed until now: the gorgeous, fierce whooshing Watermotor. The dance is so identified with Brown --partially because Charles Atlas made a beautiful film of it in 1978, when it was new--that I wondered whether it could be transferred to anyone, not to mention anyone less voluptuous than her (which is pretty much anyone). But Beasley (during a two-week DTW season-- in its intimacy a great venue for Brown) made the solo his own--a more thrashing version that suited his compact frame--and confirmed the choreography's power.

Mark Morris's Grand Duo, in a student showcase at Juilliard of "classic works," wasn't so lucky. Though the musicians did justice to the Lou Harrison score in all its jubilant forthrightness, the dancers couldn't muster sufficient ferocity for Morris's primitivist, sneakily obscene stomping dance.

****[restored] If the Cunningham troupe is thoroughly disbanded--without even a pickup troupe among the former company members (and why, why not? Why can't there be a somewhat expanded version of the RUGs, the Repertory Understudy Group? Didn't Cunningham's own ambivalence in the months leading up to his death warrant as much?)--the dances' future is likely to look more like the Juilliard rendition than like Beasley's solo in a language he is in fluent in.

The Juilliard show confirmed something I had just noticed about Morris's own dancers, at the intimate shows at his Brooklyn studio. Here's that review:

Mark Morris fans enthuse about his musicality and clarity of expression, his inspired choice of score, his wit, contemporary sensibility, storytelling genius and diverse lineage, from Isadora Duncan to Balkan folk dance. But at the 150-seat James and Martha Duffy theatre where his company is celebrating its 30th anniversary until March 27, his singular movement style strikes hardest.

At close range, you notice how much force the dancers put into their steps for the sake of precise shape and character. The skilled wielding of so much power focuses on the dancer's will, making him seem as "real" as anyone. The Morris dancer does not disappear into the dance.

The Muir, to Beethoven's settings of Scottish and Irish folk songs, and the slight Festival Dance, to the kind of bland classical score (Hummel, in this case) that reduces Morris the poet to Morris the patternmaker, the women overwhelm their scrawny male partners by sheer meatiness. The long La Sylphide tutus for The Muir and the 1950s poodle skirts for Festival Dance underscore how unlike a sylph or girl next door these women are; the astounding Petrichor - created for the company's eight women - describes what, in a better world, they might be.

The fragrant Petrichor. Photo by Brian Snyder

Petrichor, Morris has tuned in to the swoopiness of the Villa Lobos score (played live and magnificently). Over four distinct movements the dance ebbs and flows but never stops. The choreographic patterns resemble flocks and herds and tides that materialise and grow dense before disintegrating. This elusive structure allows us to sink into sensation. "Petrichor" means the fresh scent of rain, and the dance is fragrant.

For the rest of the Financial Times review and what the women become in Petrichor, click here.

For the last couple of years at City Center, I grow teary when Paul Taylor takes his bow at the night's final curtain. At 80, the master choreographer is still a strikingly handsome man--and if he has shrunk, he was tall enough to begin with that it is hardly noticeable. But he is more frail with each passing year.

In the last few seasons, he seems to be looking back. In the second of his two annual premieres, it is to vaudeville--the Dancing with the Stars of his youth as much as Cunningham's. But his is mixed up with a sit-com goofiness, too. Think I Love Lucy . Here's the start of that Financial Times review:

Several Paul Taylor dances from the past decade could be called "phantasmagoria" - the name of the second premiere of the New York season. Increasingly, the acclaimed American choreographer has set on stage a tumbled dream of theatre - or its kin, ritual. Some of these dances, such as 2010's Also Playing (reprised this year), are comic and rooted in vaudeville; others, such as the pair of Buñuelian Dream pieces from 2007, are infused with an eerie surreality. But both types - in fact, most of Taylor's vast repertory - feature shifting points of view. Taylor is a master of sleight-of-hand, with tricks in the service of truth.

Phantasmagoria is one of the revue-inspired pieces, though it begins soberly enough. Brueghel peasants, sunk in longtime Taylor collaborator Jennifer Tipton's inky shadows, pound their fists on the ground in protest at a grievously hard life. Soon, though, they have cast off their woes and grown frolicsome. To a score of anonymous Renaissance tootlers that carries on throughout the dance, the lassies squat simian style on their lads' thighs and press cheek to cheek.

Like a zealous and drunk short-order cook reduced to scraps, Taylor serves up a whole hodgepodge menu of stock characters - first as separate dishes, then as stew. Gauzy and flower-bestrewn Isadorables, a strictly up-and-down Irish step dancer (a deadpan and broom-stiff Michelle Fleet), an imperious spying nun with massive wimple (Laura Halzack, whose comic impulses turn out to rival her celebrated lyricism) and, as pièce de resistance, an "East Indian Adam and Eve", as the programme puts it.

A Bowery Bum (Robert Kleinendorst) about to trespass on three Isadorables

For more on how Taylor turns the scrappy into the revelatory--click here.

In the season's first premiere, Three Dubious Memories, it was Taylor's own mentors that hovered over the dances: Antony Tudor (his teacher at Juilliard)--with his portentously universalizing names of characters ("The Man of the Moment" etc)--and Taylor's greatest influence, affectionately satirized, Martha Graham.

Sent in a retrospective direction by Three Dubious Memories, I ended up thinking of another work on the program, the 1976 masterpiece Esplanade, also in terms of influence--in this case the older Balanchine work that shares part of its score. Here's that Financial Times review:

Revisiting a great dance, you may be struck less by its familiarity than by its persistent strangeness. Its many unfolding mysteries can make it seem disorientingly new. For example, on the opening night of the Paul Taylor company's two-week New York season, Esplanade seemed suddenly to be in secret dialogue with another masterpiece to Bach violin concertos.

Though Taylor's beloved 1975 work only shares half its score with Balanchine's 1941 Concerto Barocco, it too arises with seeming inevitability from the music. And its pleasure and revelation, tenderness and melancholy, also reside in basic steps that gain traction as they travel between dancers. Except for a desolate adagio, Esplanade is down to earth and sunny here; Barocco, by contrast, is courtly and cool. But the steps in both move like an electric current - or a lively conversation.

In Barocco, the ballerina leaps into the middle of small accommodating circles of women like a fairy on to a lily pad. In Esplanade, the architecture is more personal - one dancer balancing on the squishy belly of another, her arm stretched along the horizon. Both choreographers reflect Bach's transparency - Taylor not only with clear patterns but with everyday movement as well. Esplanade's flex-footed gallops, runs, slides, hops, and bounding leaps into another's arms speak the language of summer, shining a mirror on our most casually lovely selves.

Three Dubious Memories - the first of the two season premieres - evokes not a work from an alien dance culture but one from Taylor's own past. The choreographer dubiously remembers the mid-century "Greek" psychodramas of his one-time mentor, Martha Graham.

James Samson, chorus leader, before his impassive clan

For Taylor's delightful mangling of Graham, click here.

Meanwhile, there was the Graham company itself, at the Rose Theater in several distinct programmes including one with her Bronte Sisters phantasmagoria, Deaths and Entrances, which hasn't appeared for almost a decade. I have liked current artistic director Janet Eilber's cleaning away of the histrionics that accrued since Graham's death. It allows me to see better the genius organization the choreographer gave her later dances, which often move both synchronically--within the terrain of the psyche, where everything happens simultaneously--and diachronically, across time. That's how Deaths and Entrances, with its young girls and several sisters, works, with temporal modes sharing the stage at once.

***[restored] Now Eilber needs to work on the dancers' legs. While the troupe has the gorgeous

coil and release essential to Graham, it has lost the capacity to do those

killer swan-dives, where the leg swings out into the air like a vast sail as the body

plunges down to the floor, all while the dancer is revolving on her metatarsal. Impossible,

yes, but somehow people used do it. Barbara Morgan's iconic photographs of the early

Graham troupe testify to this fact, as well as to the tree-trunk legs of her

acolytes. Legs from another century.

Also last month, at DTW, grand Graham devotee Richard Move (of Martha @ Mother's fame) recreated the choreographer's 1964 interview with dance critic Walter Terry at the 92 Y. It wasn't simply a paint by numbers production, though. Move captures Graham's utter command of her audience and interviewer, her wisdom, and her intense loneliness, stuck in a world where even the most educated and well-meaning, such as Walter Terry (played with his indelible, irrepressible good humour by playwright Lisa Krohn) come off as clueless beside her.

Move doesn't indulge in camp here: he understands that Graham isn't just trying to be bigger than life--this isn't just outsized ambition--she is bigger. A visionary. When Terry asks a question that expects too little of dance or her, she looks at him as if he had just evaporated before her eyes and she was stuck in a mirage-inducing desert by herself.

***[restored, added to] That refusal to accommodate--not for the sake of being difficult, but because you believe entirely in what is at stake--has nearly vanished from the world. Graham expected that Terry, as well as her audience, could be spoken to without condescension or simplification, and it is exhilarating to watch. Nowadays it is not the audience who is enthralled to genius, but the other way around, with people who should be our heroes having to stoop and smile to accommodate the bozo obliviousness of whoever deigns to give them a bit of media attention. Only Hollywood stars are exempt.

The one week run at Dance Theater Workshop was sold out and thus too short. I know it is a very tricky business guestimating a show's audience, but DTW tends to underestimate. Juliette Mapp's fantastically dense and smart The Making of Americans (about which I hope to write more in the future) could have been extended for another week as well.

Alright, that's it for now. I still have a pile of other reviews from the past six weeks to organize an idea around--and post--so I may be back before the battle of the ballet seasons begins, in May.

In the meantime, enjoy your Passovers, Easters, and other rituals to survival, resuscitation and bunnies!

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments