foot in mouth: November 2010 Archives

Hmmmm.... It must be something in the air--or in me--that the experimental works this month seemed too much between one thing and another, without ever wresting their own potent identity. They felt insufficiently steeped, like a stew that hasn't sat and simmered long enough for the flavors to blend.

With Neil Greenberg's (like a vase), the steps were precise yet coded, private, partial:

Neil Greenberg's (like a vase) begins with Ruth Draper - the mid-century monologist who set Lily Tomlin on her course - impersonating a neoclassical PE teacher. She is instructing her stout young female charges in the virtues of "Greek poise". The hour-long dance both shares this high-minded exerciser's aspirations and makes even more of a hash of them than her Isadorable pupils probably did. I have never seen such well-wrought inharmoniousness.

Johnni Durango and Greenberg. Photo by Yi Chun Wu

As soon as Johnni Durango shows up in garishly patterned tights, which turn out to clash with the other five dancers' equally garish ensembles, it is clear that the Greek columns demarcating the space are a red herring. The choreography will offer only momentary hallucinations of pattern and sense. As for the steps, they abound in legs half straightened (or are they half bent?), feet that would pound if they weren't stuck on half point - in short, the relentlessly incomplete. I glimpse snatches of flamenco, yoga, aerobics and club dancing, executed as if stoned.

Of course, the bleariness is deliberate. The choreographer can do sharply evocative when he wants. At hour's end, for example, the dancers move downstage to face every which way. For once, I know what their formation is not: a line. Its absence hovers gorgeously over the moment. More typical, though, is an episode in which two dancers blow the dust off standing mikes as if preparing to sing; they do not. Most of (like a vase) is a prelude or epilogue to an unrealised main event.....

For the rest of my Financial Times review on Greenberg, click here.

For Sasha Waltz, the problem was the lurch between factuality and storytelling, without metaphor in either:

Berliner Sasha Waltz's influences are like her city used to be: divided. On one side is 1930s German expressionism, which also shaped Pina Bausch. On the other is the "just the facts, ma'am" structuralism of such Americans as Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer. Waltz, 47, has not tried to reconcile these polarities. She began her career making political dance theatre, then shifted to more architectural concerns, with the body the columns and posts, and Germany's guilt-laden history in the shadows. For the first time with the nearly two-hour Gezeiten (Tides), for an international cast of 16, she brings the forms together.

Tides is about what happens when the things we take for granted - that the ground will remain firm, the ocean not overflow - no longer hold.

The dance begins serenely, with the dancers embodying the balance and order that will soon disintegrate. In twos and threes, they slink into the room of longtime Waltz set designer Thomas Schenk, the paint peeling and wood floors soft with wear. As the light passes through each time of day and Bach cello suites alternate with the whistling of the tide, the dancers pair up to form asymmetrical mobiles so carefully balanced that no clutching or clinging is necessary. Eventually the whole troupe arrays itself like a slant of dominoes.

Balancing. Photo by Richard TermineWhen the room goes black, we hear the sound of buckling, breaking and burning. When the lights come on again, the dancers are falling across the space and the doors are shut to keep disaster out.

No such luck. In the disproportionately long second act, Waltz subjects her crew to contamination, fire and earthquake.....

For the rest of my Financial Times review on Waltz, click here.

Jonah Bokaer's Anchises fell in and out of theatrical time:

This rich collaboration between choreographer Jonah Bokaer and designers Ariane and Seth Harrison takes its name from the ailing father whom loyal Aeneas carries on his back from burning Troy. But the creators seem more interested in the ruins left behind and the Rome to come. Imagining the dancers as living structures as much as people, Anchises straddles architecture and dance, awkwardness and intrigue.The most obvious allusion to Virgil's cherished patriarch are Valda Setterfield, 76 and as arresting as ever, and a regal Meg Harper, 65 - both with Merce Cunningham in the 1960s and 1970s. The three much younger cast members occasionally lift the women on to their backs or shoulders or suspend them overhead.

More frequent, though, are tableaux not of dependence but of connection - a chain of dancers hand in hand, for example, with one sitting on the floor, the next kneeling, the third lunging, the fourth standing. Sometimes the dancers cluster like a family. Sometimes they face each other like a ballroom couple, with a few bodies sandwiched between. Sometimes large cubes take the place of people in these deliberative arrangements.

The effect is lovely yet static.

You do not feel the movement between generations or even the passage of time. In contrast, the swooping, arcing, twisting solos and duets for James McGinn and a stunning Catherine Miller sweep us into the moment. Off-kilter gravity and voluptuous force are not only unusual dynamics for the choreographer, they also bring into relief the older dancers' circumscribed possibilities.Still, the mix of the dancey with the architectural risks inducing torpor in the viewer....

Click here for the rest of the Anchises review for the Financial Times.

With The AWARD Show!, the trouble was between artistic vision and expedience (We need a winner!):

Imagine So You Think You Can Dance without the flashing lights, screaming fans and millions of TV viewers, and voilà: The A.W.A.R.D. (Artists With Audiences Responding to Dance) Show!, where not the dancer but modern dance is the star.The show's aim is true: the top vote-getter of the 12 finalists gleaned from some 200 entries wins $10,000, a fortune in this cash-starved field. And since it began in 2005, the contest has caught on, with editions in Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle.

So I wish this self-described "experiment in democratic ideals" did not suffer from democratic realities as well, such as the sound-bite mentality. The three dances voted on to the final night existed in a vacuum, where world and dance history have no place. The popular vote dredged up that hoary notion of modern dance as purveyor of timeless psychological truths, decked out in allegory.

Choreographer-dancer Yin Yue's Torn combined in a single figure martial arts heroine and swamp princess. Satoshi Haga's Thread, in which two dancers kept their fingertips touching, veered from movement exercise to arid symbol, with urgency and rich suggestion blessedly intervening between those poles. Only choreographer Helen Simoneau's robotic solo was consistently layered. Playing with the history of dolls in dance - The Nutcracker, Coppélia - she moved with a strangely sensual stiffness.

Helene Simoneau. Photo by Matthew Murphy.

Helene Simoneau. Photo by Matthew Murphy.

And, reader, she won - though if it had been up to the hoi polloi rather than the four expert panellists brought in for the last night, who knows?

Maybe the problem isn't democracy but the balance of powers. The executive branch - the artist - needs beefing up.......

Click here for the rest of the AWARD review for the Financial Times.

Only with Keely Garfield, whose show is already a month old, was the betweenness gloriously to the point:

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union met in this East Village establishment (long before it was called the Duo). Yiddish-theatre idols clomped across its stage, with its gold-painted proscenium and murals of plump 18th-century ladies. Francis Ford Coppola shot a scene for The Godfather II here, and Andy Warhol organised porn movie nights. So why not London émigré Keely Garfield, whose MO is precisely the unlikely connection?

I will not hazard a summary of the choreographer's latest tragicomic concoction, commissioned by Duo in its inaugural year as dance producer. Twin Pines has nothing so straightforward as a plot. If it is about anything, it is about painful, hopeful approximation - about making use of the materials at hand, however rudimentary or plasticky, to dream oneself out of despair.

Twin Pines is organised around trees - or rather, this being Garfield, stumps. The stump symbolises the soul, the programme says - stunted, with the possibility of later growth.

The characters for the first act, in the studio above the theatre proper, include Brandin Steffensen's stiff woodman, later enrobed like a king at a coronation in a fluffy pink sleeping bag; Anthony Phillips's Zen master, coming to a bad end; dulcet-voiced folk singer and straight man Matthew Brookshire; and the indispensable Garfield.

Garfield between the stumps. Photo by Cyrus RaThese people attempt various metamorphoses. With coat hanger for crown and dangling shoelace as tinsel, Garfield becomes a queen, for example. The beige tool apron trailing between her legs serves as royal train. Later, a different kind of hanger (plastic and white) figures as leaves and she as a tree, rustling then wrestled to the ground and stripped by axe man and Zen master.

The performers enact these scenarios with the hilarious sombreness of a child in a skit she has learnt by heart. But the scenes do not cloy. Expert pacing and deadpan delivery guarantee that the players do not seem to be impersonating children so much as heading down the same rabbit hole of iconoclastic imagination.

The show becomes more dancey when it descends to the main theatre for "Flesh", the second act. The introduction of gorgeous dancer Omagbitse Omagbemi invites this transition. Twin Pines' fascination, however, depends on awkward inhabitation, the gap between the stiff little dances and the soul they are meant to invoke - and sometimes, miraculously, do.

Voila: my month of Mondays, with a Sunday thrown in for good measure.

This season we've had contemporary European dance not only at BAM, the usual suspect, but also at the Joyce, with Belgium's Ballets C de la B earlier this month and more recently Cedar Lake, its reputation as purveyor of B-list--or at least green--European choreographers (with a few A-list Israelis in the mix) now solid.

I sound typically New Yorker, don't I? Jaded to the point of provinciality. In fact, two of the five choreographers for Cedar Lake's two programmes really excited me. And they were the youngest two--so they just may get even better.

Here's the section of my Financial Times review on 26-year-old Alexander Ekman's ebullient Hubbub:

His New York debut, for the full troupe of 15, applies pompous social critique and dancers' running commentary to itself -- a jumble of angular posturing on high pedestals and fiercely staccato gestures executed in tight formation. The parodies of art talk are not exact enough, but the reckless invention is a giddy pleasure.

For the whole Cedar Lake review, click here:

Cedar Lake also presented the first complete work by Londoner Hofesh Shechter to be seen in New York. The start of my Financial Times review:

I know there is an upside to the European trend of liberating "ballet" companies from ballet, but Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet's second programme at the Joyce mainly testifies to the downside. With Dutch freelancer Didy Veldman's Frame of View and Norwegian stalwart Jo Stromgren's Sunday, Again (reviewed last week), the story ballet gives way to lax, latter-day dance theatre, ebullient in its unfolding and only half-committed to its organising conceits. Stromgren's is badminton and Veldman's is doors, but the dances cannot seem to remember - wearing us out with distractedness long before they manage to conclude.

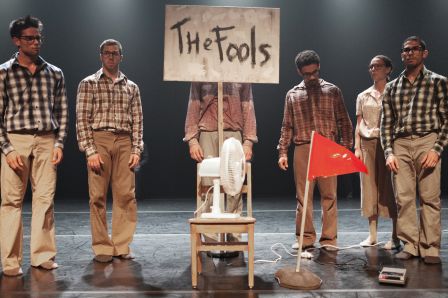

Happily, Hofesh Shechter's The Fools - substantially reworked for Cedar Lake after a 2008 premiere for the Bern Ballet - would be welcome even in better company. Sure, the first full work to appear in New York by this British-based 35-year-old Israeli sensation has its flaws. The black and white title credits that appear at intervals on a small screen upstage, for example, would more effectively evoke old movies and the retreat they offer into hope and memory if the screen were fit for a movie palace too. Likewise, the quick cut from winsome Scarlatti sonata to the sound of hollow wind seems like an accident. Musing about sound engineering, I almost failed to notice that aspiration and desolation had just collided.

Yet even these unrealised elements do not ruin the mood, which is as dense as nightmare.....

Shechter's fools. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

Shechter's fools. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

For the rest on Shechter, click here.

As a reviewer, you are addressing your readers, not the choreographer. So I will take this non-review opportunity to urge Msr. Shechter to end the dance earlier, just after the scene pictured above, when the wind is blowing on tape and via fan and the fools have left their flag and message behind. As it is, the ending is pure, unnecessary coda.

I caught the first section of Frenchman Angelin Preljocaj's Empty Moves when it first appeared at the Joyce in 2006, but really only took in its measure in its full, hour-long form at BAM earlier this month.

The rowdy Milanese students we hear on tape objecting to Cage dismantling Thoreau's journals word by word--as a form of homage--complete Cage's score, and Preljocaj's choreography completes it even more (something only possible, perhaps, with Cage). Without the composer and dancers' serene refusal to be deterred, we wouldn't feel so immediately their connection to civil disobedience--that thoroughly Thoreauvian notion.

Here is the whole short review for the Financial Times:

The riot at the first Rite of Spring has nothing on a 1977 performance in Milan of John Cage's Empty Words (Part III). The impish composer reads a mashup of words and spaces between words (aka silence) extracted from Thoreau's 14-volume Journals. An hour into the two-and-a-half hour recital, the audience of art students begins a rhythmical clapping and jeering. Cage never flags.

I used to think his choice of Thoreau was merely a tease: a massive stack of takeout menus would have done. But French choreographer Angelin Preljocaj's stealthily uplifting Empty Moves (parts I & II) has convinced me otherwise. The hour-long dance for four embodies the composer's resistance to the battalion of ideas about art and meaning, thinking and being, that have defined western thought for centuries--and thus brings to mind Thoreau's own refusals, his civil disobedience. Empty Moves proceeds with benign equanimity in the face of the students' long-ago but still alarming obstruction.

This is a dance graced by an abundance of unpredictable invention. Empty Moves expresses a tender interest in the body's most eccentric or banal parts, from nostril to fingertip to hip socket. Movement travels by chain reaction along these unlikely paths. Time moves as if something deeper than will drove it, as when a flock of birds rises from a wire.

Left to right: Fabrizio Clemente, Yurie Tsugawa, Julien Thibault, and Gaelle Chappaz (on floor). Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

The art students have grown so loud that my pulse quickens. Even 33 years later, their violent contempt is frightening. But the persistence of Cage and, by proxy, the dancers rises above the noise and the dance comes flooding back.

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments