foot in mouth: April 2010 Archives

A good deal of experimental dance today--as in the Judson Church days--is closer to performance art. It examines its own parameters; the movement may be minimal. And yet choreographers exist in a nearly invisible parallel universe to visual artists. While choreographers and their audiences know what's happening in gallery and museum, the reverse isn't usually true--not on this side of the Atlantic, anyway.

I'd say, Fine, we don't need them, if it weren't that performance art in the art world is accorded value--bought and sold so it funds the artists and their work--and dance could use that kind of support. Plus, dancers' understanding of gesture often makes the dance species of performance art less sophomoric in its conceptual moves. Choreographers understand better than artists, who aren't always practiced in using time, that the moment will always trump the idea. They work with that fact, which gives the piece greater density.

This brings me to Maria Hassabi and Robert Steijn's Robert and Maria, which took over Danspace Project at St. Mark's Church for three days recently, and will emerge again at a few performance festivals in Europe this spring before disappearing for good.

Here's a part of last week's review of Robert and Maria for the Financial Times. Then on to Marina.

Robert and Maria covers about 6 sq ft of ground - and lifetimes of feeling. In the final offering in curator Ralph Lemon's event series "I Get Lost", itinerant European performance artist Robert Steijn and New York-based dancer-choreographer Maria Hassabi begin with their backs to us and an arm wrapped around the other's waist. They end in the same amicable position, but facing front.

In the hour that separates these mirror images, the large craggy man and the beautiful diminutive woman stand facing each other, their profiles to us; they face each other kneeling; they lie on their sides, face to face. If Eadweard Muybridge had photographed not a horse's gallop but feelings growing, shrinking and wavering across body, face and the space between two people, it might have looked like this.

The piece progresses via small adjustments in the performers' stances - a hand grazing a cheek or slid into a pocket - executed so slowly that Hassabi shakes and Steijn sways. The dancers are not merely maintaining their emotional equilibrium, they are invoking their feelings through their gestures, like Proust's narrator with his memory inducing madeleine.

Sometimes Steijn becomes Hassabi's inverse, hollowing out his chest so she can draw closer. Sometimes they suddenly draw apart. But they always look into each other's eyes, which often well with tears.

Robert and Maria, beside a bouquet of footlights, all utility and decorative beauty in a dance that has its own approach to both. Photo by Antoine Tempe.

New York has lately become a hotbed of intimate, highly public performance art. To enter the Marina Abramovic retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, for example, you must pass through a gauntlet of nude bodies. At Tino Sehgal's Guggenheim show earlier this spring, the first piece you came upon was a couple rolling around on the atrium floor. More exhibitionist than self-exposed, these works convert viewers into hapless voyeurs. They throw us back on ourselves when we are at our rubbernecking, vacant worst.Steijn and Hassabi keep their clothes on and their hands largely to themselves; what they do reveal is...

For the whole story, click here.

Now onto MOMA and the thousands of visitors further enshrining art world diva Marina Abramovic. I am baffled that even the art critics who had problems with the show made so little of their problems. They said Abramovic was vain--and sure she is. (Check out the New York Times Magazine story on her stoical self-grooming practices: a vanity converted into something else by its sheer extremity.) Or they said that the work could not survive its moment, which is also true, or could not survive being transferred to other performers-- true as well. But it would be worth asking what kind of art depends so heavily on the merging of body, artist, and the present that it can survive so little translation: neither of person nor of decade. And what is it about this moment in particular that the art cannot survive? The show's title is "The Artist is Present," so it invites these questions.

The myth of the suffering artist that Abramovic exploits by sitting on a hard chair or a bicycle seat half-way up the wall for a gabillion hours was tiresome enough when she first recycled it in the est-y '70s, with self-realization via non-denominational exploration and humiliation all the rage. Now that reality TV offers all sorts of different paths to fame via abjection and overexposure, it is worthless. A redundancy.

In one of the latest TV endurance shows, Hoarders, on A&E, the homebound packrats don't do anything either to earn their claims on our attention, beyond peeing and sitting in one spot--and, oh yeah, not throwing anything away. Abramovic does not have stacks of unrecycled newspapers cluttering her space; she is an Artist, after all. In place of contestant-as sufferer she presents artist-as-sufferer. But otherwise she's working from the same premise: her presence suffices. She should get herself a gig on TV.

Seriously. Critics who complained that MOMA's grandeur and institutional weight deprived the work of its intimate immediacy might have considered that the culture deprived it of immediacy long before MOMA got around to the task. We are too used to spectacles that make claims on the real to grant Abramovic any special status. (The long train of admirers queing up to sit in the chair opposite her would disagree.) But put her on TV--with a live audience cheering and laughing each time she blinked, there in her chair-- and maybe the work would gain traction. Or at least a sense of humor.

Faye Driscoll's 837 Venice Boulevard, which premiered at Here in the South Village in late 2008, amazed me so thoroughly that it's no surprise her latest, at Dance Theater Workshop a couple of weeks ago, amazed me somewhat less. It hardly had a chance. Still, I remain impressed by how Driscoll harnesses dance and the best experimental theater's story rhythms to expose the seams between social behavior and antisocial behavior (the libidinal rising up and causing public havoc). Here, belatedly, is some of my Financial Times review:

You probably haven't heard of Faye Driscoll, but if experimental dance theatre ever emerges from oblivion, you will. Since the birth of the Greek chorus and the Dionysian rite, dance has been linked with ecstatic states. The 34-year-old LA transplant unites them again, but not for the usual reason of delivering a sexy number. Instead, her giddily gruesome comedy There is so much mad in me reveals what communal forms of extreme feeling leave in the dust - mauled and pummelled - as they ruthlessly pursue their ends.

Amanda Ringger's lighting veers from glowing puddles in the dark to blinding brightness. Brandon Wolcott's soundscape slips from thundery rumbles to hollow New Wave beats to silence. Meanwhile, a ménage à trois re-forms as a twosome plus taskmaster, or the anarchic play of all nine dancers turns vicious and mob-like before it mutates into an oddly askew aerobics routine.

Sometimes an impulse towards harmony distracts the crueller drives. Contestants on a daytime talk show vie for the title of Biggest Sufferer of Outrageous Fortune. (I vote for the lady with two vaginas whose cheating husband has knocked up a male stripper.) But before the winner is declared, people have forgotten their troubles and descended into a telegenic orgy.

Half the fun of There is so much mad in me lies....

I am the odd woman out re the Trisha Brown miniprogram at the Baryshnikov Arts Center last week. My esteemed Artsjournal colleague Tobi Tobias loved it, as did Roslyn Sulcas at New York Times, Eva Yaa Asantewaa at Infinite Body and Kathleen O'Connell at Danceviewtimes (whom you should look out for if you haven't yet: much insight). In their enthusiasms, they wrote more eloquently than I did, being grumpy.

So what's my problem? I offer a few things in the review, but to frame it somewhat differently, Brown has enough ambivalences about theater that she can make me uncomfortable watching, without that discomfort leading anywhere fruitful. It's fine to be ambivalent about a given of theater, but unless the choreographer can take that private neuroses and turn it into a matter of theater (to tweak Freud's salvo about the goal of psychoanalysis: to convert "neurotic misery into common unhappiness"), the un-ease gets transferred to us.

With the two BAC dances, Brown's qualms by no means overwhelm the experience. The accoutrements of theater--the rolling fog in Opal Loop, the back turned in If you couldn't see me--are so well integrated into the dancing that they almost seem necessary to it. And she is unequivocally in love with dancing: that much is abundantly and deliciously clear.

Anyway, here's some of my Financial Times review (though you have to click to get to the complaining):

The most consistent pleasures that Trisha Brown offers are not dramatic, musical or visual but kinetic. She reveals the muscle and momentum that drives a step so that we sense what it might feel like to execute the move. The 73-year-old choreographer makes dancers of us.

The company's year-long 40th anniversary celebration, which extends from the US to Europe, began on Wednesday with Leah Morrison turning her back on us.

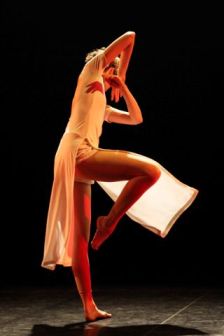

Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

In If you couldn't see me the dancer never does show her face, but we can see her - or at least the part of her that matters to Brown. Morrison complements a swing of her leg with an undulating shoulder. She descends suddenly into a deep plié. She lets an animal stillness overtake her as she extends an arm upward at a slant as if signaling a thought. Last year Morrison won a Bessie - New York dance's Oscars - for her performance of this 1994 solo, and it is clear why. She brings out the delicacy and fullness of Brown's approach, in which everything counts as a detail and nothing does.

The 1980 Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503, the only other piece on this appetiser of a programme, begins with prancy feet - imagine reined-in horses - and anxious, air-massaging hands. As sculptor Fujiko Nakaya's fog waterfall rolls down the theatre's back and gradually floods the stage, the four dancers iron out their limbs and move with full-bodied clarity among the clouds.

Even with all their bodily fullness, however, these works do not let me forget what they omit. Of the two pieces....

For the whole review, click here.

So, unlike Movin' Out, which was almost unanimously hailed (though not by me) or the Dylan dancical, which nearly everyone despised (including me), Tharp's third foray on Broadway in the last ten years, Come Fly Away--to a Sinatra medley, with the man singing, inimitably, from the grave and the orchestra live--has divided critics so drastically that the New York Times staged a contretemps between its theater critic Charles Isherwood (pro) and its chief dance critic, Alastair Macaulay (con).

Both critics were at their worst, with Isherwood equivocating before recognizing what he was up against and Macaulay resorting to the sort of surliness that sours debate. When Macaulay asserts, "The nightclub where people need to keep carrying on like the pathetically exhibitionistic creeps in 'Come Fly Away' is not a nightclub in which I want to stay; they're bores," what else is there for Isherwood to do but repeat his words? "'Pathetically exhibitionistic creeps' "? But also "'bores' "? Still, the nature of their divide has been pretty typical.

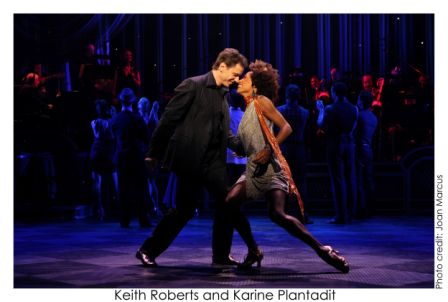

Complaints have centered around the weakness and flatness (and, less often, dislikability) of the characters, the choreography's vulgarity and busy-ness, and the lack of story. Those who enjoyed the show--I'm one of them--agree it doesn't have profound characters, but it does have profound dynamics between them. Example: when the more passive member (Keith Roberts) of a frisky, taunting couple suddenly turns the tables to push his partner around--and she (Karine Plantadit) thrills to it. I've known couples who were ugly like that, and Tharp is brave, novelistic, to show it.

People that liked Come Fly Away also didn't mind that it didn't have much of a story beyond the portrayal of these couples in love and war. The Dylan and Billy Joel dancicals did try to tell stories, and diminished the songs in the process (or Dylan's songs; Joel's came small). Come Fly Away doesn't try to turn a song into a story, it turns a Broadway show into a song--or rather a ballet.

I confess, I thought the first act was too wham-bam. My muscles ached watching it and I wished all the dancers except former Cunningham dancer Holley Farmer, who maintains an insouciant ease, would honor Sinatra's own example and cool it. (You can be tough--menacing even--while cool. In fact, if you're going to be effectively threatening, you have to be cool. Get hot and bothered, and the game's up.) When intermission hit I wondered where Tharp could possibly go from here: she seemed to have taken each couple's dynamic as far as possible.

But in the exceptional second act, she shifts gears. It's not the characters she takes farther, it's the dance--and dance on Broadway. When she enters us into the late night dissolution populated by only the lonely, still out and nursing their wounds or drowning them in drink, it turns out to be a familiar place for concert-dance goers: a dream world, with a poetic logic that rides over and under the occasion and thickens it by contrast and complement.

At one point late along, the dancers clasp hands and do a little grapevine with their backs to us like you might find in a play inside a play of Shakespeare's, put on by "mechanicals". The folk dance gratifies a need for connection that all the coupling in the world--the world according to Tharp--cannot satisfy.

Here's a piece of my Financial Times review, which came out about 10 days ago:

Twyla Tharp imagines romance as a war of wills. Frank Sinatra injects even the most googly-eyed song with a strain of menace, as if he had fallen in love despite himself. The two are a perfect match, and Broadway's Come Fly Away proves it in startling fashion.

Tharp's third jukebox dancical has as much working against it as the heavy-handed Movin' Out, to Billy Joel tunes, and the Dylan flop that followed. The script amounts to a medley of songs, which Sinatra delivers on tape to the accompaniment of a live orchestra. The setting resembles a nightclub in an airport. The show doesn't really feature characters - we would need a plot for that - so much as romantic propensities. One couple gravitates towards innocent clownishness; another maintains a cool insouciance; a third begins with grandstanding and friskiness, detours into spirited S&M, and finishes off with the aqueous lovemaking that emerges from sleep.

And yet Come Fly Away far surpasses Tharp's other two Broadway shows because she has finally accepted what a song can do better than it does plot and character. In a seemingly casual arrangement of the most inventive dances she has created in years, the choreographer concentrates on metaphor, feeling and rhythm: poetry.

Perhaps to reassure the audience, the first act resorts to the usual Broadway tropes, but rendered with masterly precision. The eight leads don't just strike a pose when they saunter one by one down a staircase, they freeze on the hippest beat of the hopping "Come Fly With Me" as if a flashbulb had gone off.

By the second act .....

For the whole review, click here.

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments