foot in mouth: February 2010 Archives

Mark Morris, Paul Taylor and--less heavy--Lar Lubovitch all have seasons this week and next. And I have reviews of them.

I'll keep adding at the top as the week progresses, so the latest on top.

Friday night (first program) of Lar Lubovitch was one of those times where I felt keenly grateful for the dancers--or, in this case, one dancer, Reid Bartelme--for improving on the material they'd been handed. I generally feel that dancers are only as good as the choreography, but occasionally they're able to see more in the steps--see it in the right direction--than the choreographer did. Lubovitch has succumbed to all his worst tendencies on this program--and needs all the saving he can get.

I should say, I have a real fondness for the choreographer: when I was a teenager he came to the Bay Area with a company that included a young Rob Besserer (lately of Hard Nut fame) and maybe a young Mark Morris (though I can't recall him, so maybe not), and they did a Phillip Glass dance, North Star, before I'd seen so many Glass dances that I was weary of them, that made me feel that if there were any kind of dancing I would want to do forever and ever, this would be it. Its kinetic appeal, its flowiness, was dance Heaven. I wonder if I'd have that reaction now.

Anyway, here's some of my disgruntled review of the present-day company, which came out today in the Financial Times:

The first programme in the Lar Lubovitch troupe's two-week season offers a dumpster's worth of threadbare moves. The men fall on their knees in triumph or, alternately, despair; they raise their palms to the heavens in exultation. The women signal "helpless glee" by pedalling through the air, hoisted up by partners who proceed to "transport" them - in the non-vehicular sense - by turning them every which way.The accumulation of hackneyed moves wouldn't matter if Lubovitch didn't possess real strengths. The choreographer, whose four-decade career has included commissions from top ballet companies, is renowned for spirals of movement that rise from hips to torso and out the tips of a dancer's fingers like a luxurious curl of smoke. A whole dance can unfold mellifluously, with group passages swirling into solos, and curves into circles. The downside is a lack of texture and, in a desperate attempt to compensate, those cheesy expressions of passion.

You would think the various species of jazz that Lubovitch uses this season would prove the perfect antidote. Whatever its style, jazz is all about texture - mercurial improvisation against a steady bass line. But somehow the music only throws the dances' blandness into bolder relief. The rhapsody of Coltrane's "My Favorite Things", for example, seems to glue the dancers to the floor. To the saxophone's bird flight across a continent and its sweet squawks of freedom, Lubovitch offers not jazz but a generic jazziness.

It wouldn't take much for the choreography to improve drastically, though. Snip the ribbons of movement a few times, tie them into a few knots, crinkle them a bit, and voilà. When dancer Reid Bartelme does these things - varying his attack, his gaze's direction, the movement's stretch - the dance grows instantly deeper and brighter.

Sometimes Bartelme...

For the whole review, click here.

Here are the first two paragraphs of my Paul Taylor review, in the Financial Times today.

For space reasons, I think, they cut a line--the one about the "speed freak love paradise," which perhaps only makes sense in an intuitive way, where you understand how seemingly unlike phenomena, such as the fluorescent colors and power shoulders and aerobicizing and lizardy amphetamine-fueled thrum, emerge from a common root. Or maybe it only makes sense if you're from Berkeley. I blame the whole tacky, sordid decade on Reagan. I remember me and my friend Alison, who lived on a houseboat and seemed quite ready to pull anchor and drift out to sea at any moment, huddling over cups of coffee and wondering why there wasn't a great outcry in the land about this man our president who kept going on, in his genial, depthless way, about a cartoonish Evil Empire he was going to make happen. It terrified us.

Paul Taylor's river of dances is so deep and wide that you could see six shows in the current three-week season without repeating a piece. The great American choreographer is consistent in the number of dances he offers nightly - three, with none longer than 40 minutes or shorter than 20 - but otherwise he puts a premium on variety. A Taylor evening swerves from the antic to the lyrical to the brutish and apocalyptic - sometimes within a single work.

Wednesday opened with a dance from the doomy column. With the dancers swaddled in those synthetic workout trousers that were supposed to slim your thighs, sweaty Syzygy reeks of 1987, the year it was made. Donald York's synthesiser score of bleeps and blurps must have inaugurated a whole new genre: Trekkie jazz. The movement is all flailing limbs and thrashing, discombobulated heads. In stand-out solos, Michael Trusnovec - spectrally thin this season - gets lost in a gritty inner world, which pings him with invisible threats and enticements every few seconds. Straight from the era of "Evil Empire," Syzygy offers up a speed freak love paradise where paranoia reigns.

The dance has survived its time because it is so indelibly of it. By contrast, the premiere Brief Encounters and the recent, acclaimed Beloved Renegade (reviewed here last year) commune with history, as often happens in....

For the whole review, click here.

And for my Morris review for the Financial Times:

I know everyone is loving his world premiere, Socrates, and, this being Morris, I'll probably love it too once I've seen it a few more times, but the first time around, I felt intermittently irritated by the visualizations of a libretto that is profound in its general drift--and that it has such a drift, that Socrates is such a calm spirit among the storms of other people's desires--but not in its every word. Do we really need walk acted out? On the other hand, the way Morris multiplies and refracts Socrates, so we see him as larger than his individual life, is powerful, and the Isadorable, Greeky steps are affecting.

I didn't say much of this in the review--blew most of my 400 words on the dance that really moved me, Morris's single silent one, Behemoth. A very mystical work: mysterious in the way it progresses and where it takes us.

Here's the start of my Financial Times review:

In that rare species, the silent ballet, the steps often feel arbitrary, because there is no music to give them an immediate reason for being. But in Mark Morris's tremendous Behemoth, the moves seem magical--arisen from some secret, unknowable place.

"Behold now behemoth, which I made with thee," God boasts about the monster he has created together with the pious Job. The monster to which Job is yoked is outrageous misfortune. For the musically minded Morris, it is silence, out of which supplicants, prophets and martyrs emerge.At first, the dance's steps are opaque. When the 15 dancers in the 1990 work settle into wide squats that declare "I am here", you wonder where. They circle a relaxed leg in the air like the half-hearted needle of a compass. Eventually, their language becomes more human and pointed, with them shielding their faces from an invisible attack or falling back against a companion in Christlike submission.

Behemoth does not come to a glorious conclusion. Each time the lights go out in a dance divided by such blackouts, you think, "This could be the end - or it could not". That's the thing about real suffering: it is too dark for the dramatic arc.

Artistic strictures seem to have inspired all three dances at BAM....

For the rest, click here.

Posts here in the next six weeks are going to be pretty barebones: links to stuff Foot contributor Paul Parish and I have written elsewhere, sans photos or anything, for now. (I may gussy them up later.)

But in case you just want to head direct to go, the Financial Times allows you about an article a day, which is certainly enough for the dance offerings (by me and the glorious Clement Crisp). You just have to register, and it's free. I write for them about once or twice a week, depending on space and openings.

Here's the Financial Times website's theater and dance page.

Here's its weekday arts page.

Paul writes pretty much every week for the Bay Area's gay weekly, B.A.R.

Here, for example, is a taste of his astounding review of Christopher Wheeldon's latest for San Francisco Ballet, Ghosts, as well as a whole panoply of Balanchine miracles:

What do we mean when we say something is a classic? Aside from the throwaway slang sense, "classic" means it's something that you'd want to see or hear again, because there was more there than you could get the first time. If you still think it's a classic after the third time, it's because you're still sensing ways it coheres that make it answerable and speak to you from an even deeper level, as if it knew you in return.

Wheeldon can give you that feeling. He can let the dancers' weight pour down through the body into the floor (which was developed by postmodern contact-improv dancers) and make it into an oceanic spectacle. Ghosts might be showing us the Wreck of the Titanic in extreme slow motion. Waves of dancers pour across the stage, sometimes sliding down onto their backs, receiving the weight of another dancer as if the impetus came from beyond themselves. The corps dominates the ballet to the point where it seems an organism, though there is a gorgeous, melting pas de deux (danced ravishingly by Yuan Yuan Tan and Damian Smith) and a very vivid trio dominated by the diva Sofiane Sylve, who alone of all the dancers seems to be fighting for control, and even at the end seems to be swimming as if on a dolphin's back to safety as the curtain comes down on the whole doomed world.

For the whole amazing review, click here.

You can check Paul out on a regular basis here, on the BAR arts page. I don't think they archive things, so you pretty much have to visit within the week. The paper comes out on Thursdays.

And, if you don't know about this resource already, one of the best dance links services, for Britain and the States, is the UK's Ballet.co reviews database, since the late 1990s. You can check by name of work or company or country or just browse each day. Both Paul and I tend to get linked there.

Ballet Talk also has a links page, and though it only does ballet and there is no fancy search engine, it does do features, which Ballet.co doesn't do much of.

Phew!

From me this week:

--A review of the opening night of the New York Flamenco Festival, in which one Rocio Molina, age 25, blew me away--and the art form wide open.

--A review of a Balanchine double hitter at City Ballet that demonstrates inspired curation. The ballets are interesting together and Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 resonates beautifully with Peter Martins's Swan Lake, which the company danced last week.

--[NEW, Sunday] A review of Robbins favorites Dances at a Gathering and West Side Story Suite, excerpts from the musical set by the choreographer in 1995. I didn't have room to mention it in my review, but the suite is worth catching for Andrew Veyette alone, who captures the loose, menacing cool of 1950s street thugs like it were his home turf. (Not that I really know what boys in the 'hood were like then, but I've watched my James Dean flicks.)

You'd think ballet would be good at expressing the exhilaration of love, and it is, but only if it can cap it off with betrayal, tragedy, death! Consider Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, La Sylphide, Giselle, Scheherazade, La Bayadere--not to mention the moderns, Balanchine and Tudor in particular. (Ashton is more cheerful.) Maybe choreographers think it would be just too easy--too cheesy--to exult in love in dance, the native tongue of emotional exultation.

But we do have the Nutcracker, where a sweet girl not only gets to have her prince but eat a world of candy too. (I mean, it couldn't be that she gazes upon mouthwatering delectables--dancing sugar plums, marzipan, Arabian chocolate, candy angels--for an hour and then doesn't get to enjoy any of them, eventually, when no one's looking, could it?)

The best love dance I know is Mark Morris's for Drosselmeier's nephew and Marie (aka Clara) in The Hard Nut, his version of the Nutcracker, and I don't think it's an accident that this is a modern dance. Marie does the plainest steps over and over, as if she's trying to acclimate herself to this new amazing feeling, periodically lunging and flopping forward as if her infatuation had turned her body to jelly. The duet ends with her running up to the lad and kissing him, then running away so she can do it again--and again. It's so sweet and funny--the giddiness so recognizable and that they kiss on every high note, as if romance always moved to the beat because it is inscribed on our hearts, whether or not we've experienced it in the world before. (There's a Hard Nut video, but it doesn't approach the live experience. I have that on others' authority, too. Here, though is one scene, with the unisex snowflakes wearing icecream swirls for headdresses, which gives you some idea of the spirit of the dance.

.)

*[Musical references corrected.] To celebrate Valentine's Day I'm guessing, the New York City Ballet gave us Peter Martins's streamlined but otherwise full-length Swan Lake last week and now moves on to one of its inspirations: Balanchine's Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 (known for decades as Ballet Imperial, as it is still known in certain quarters). Balanchine heard the tragedy of Swan Lake in various Tchaikovsky works: in the "Diamonds" music, from Symphony No. 3, for Jewels (which ends the NYCB winter season, next week), and in Tchaikovsky's Suite No. 3, from which Balanchine created a ballet of the same name. But I'm most eager to see his ballet to the piano concerto because the terribly sad ending of Martins's Swan Lake alludes to the terribly sad middle of this Balanchine, where the--I was about to type mother, and there is something maternal about her--ballerina bends down to hug the lonely danseur before departing through a narrow gauntlet of women. I can't remember whether in the Balanchine she bourrees backwards as she does in the Martins--keeping her eyes as long as possible on him. I think not, but we'll see.

I strongly recommend the lovelorn All-Balanchine program this week: besides Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2, the equally emotionally illuminating--and trying--Liebeslieder Walzer.

Here is a chunk of my Friday review for the Financial Times on Martins's Swan Lake:

New York City Ballet is distinguished not simply by brief and plotless dances, but by how transparent they make the operations of art. Illuminating and intensifying experience, the ballets - by Balanchine in particular - are like magic tricks that are all magic and no trick.This season, however, Peter Martins' renditions of iconic story ballets dominate. The balletmaster- in-chief strips story of connective tissue and thus sense. Balanchine kaleidoscoped a story's layers into metaphor - poetry; Martins simply adds or subtracts elements.

Swan Lake, the season's final story offering before we return to plotless Balanchine and Robbins, brings home the difference, because Martins has built his four-act ballet around Balanchine's sublime two-act version. Rather than making him look worse, however, the proximity to genius makes Martins choreograph better. Swan Lake is his best story ballet.

Martins has good instincts but bad follow-through. His addition of a jester to the court scenes, for example, has promise: wherever protocol and hierarchy rule, there is room for a "licens'd Fool" to turn things on their heads. But this jester doesn't even mess with the steps. And what Martins gains by enhancing the lustiness of the national dances that preface evil Odile's seduction of the prince, he loses when he throws in a chaste shepherdess number and a plucky pas de quatre that seems to have flown in from fairyland.

In the Balanchine-indebted lakeside scenes, on the other hand, the steps mean many things at once, each of which deepens the drama. The swan corps shift places like a flock on the wing but also like waves on the eponymous lake of tears. As animals, these creatures live what they feel. In the Swan Queen's final moments with Prince Siegfried, they curl up...

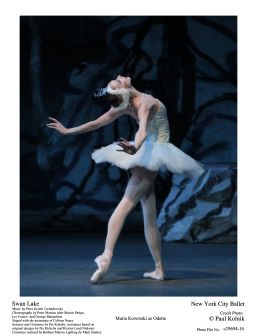

Isn't she lovely? Maria Kowroski, swan.

Photo by Paul Kolnik for the New York City Ballet.

For the whole review, click here.

I am in the minority--among ballet aficionados and critics, too, I think (though I haven't read all of the reviews)--in preferring Martins's Swan Lake to his Sleeping Beauty, which played earlier this season. This isn't to say there aren't big problems with the Swan Lake, only that it seems less dully docile, and has sublimity and tragedy where you need it: in the promise-making and parting scenes by the lake. That is, whatever problems with coherence this Swan Lake has, The Sleeping Beauty's are more egregious.

As is often the case when one is alone in an opinion, this general preference depresses me, because it suggests that those who are really devoted to ballet care less about the integrity of a work than that it hit various high notes and/or give their favorite dancers longer in the spotlight.

I could understand their point of view if we weren't talking the house of Balanchine, whose mission was to have the choreography be the star, which doesn't mean the dancers don't matter but only that they don't matter more than the dance; Martins's Sleeping Beauty doesn't allow the dance to matter much. So who cares that it includes all the iconic moments like some greatest hits album--the Rose Adagio, the variations of the fairies, the Vision Scene?

Many viewers and critics who have admired this or that dancer in Martins's production were appalled by ABT's Sleeping Beauty a few years ago, about which I have gone on and on. (I've also gone on about the Martins version already) And, sure, ABT's may have been a fiasco, but it was a mainly intelligent and brave fiasco--in which the choreographers largely understood the story and the characters (minus the storybook final act, which they so truncated as to make it hardly read), even if they hadn't entirely figured out how to turn it into good dancing and good theater. For example, they understood that the story depends on some suspense.

This is how friend and Foot contributor Paul Parish put it to me in an email recently when I was complaining that the Martins production was making me forget why The Sleeping Beauty has been such a big deal for a century.

Paul starts with the final wedding pas de deux in which the Prince rotates Aurora back and forth in attitude (the crook-legged position) so we can see her from all angles.

That attitude based on a little figurine of Mercury you can hold in your hand and rotate-- the statue itself is famous for how it continues to "compose" as you rotate it; there are three major faces and it is lovely in all the intervening ones -- has this way of reminding you of the larger mysteries of the blind side: what's going on that you're not thinking of, what's going on that you can't see, who's brooding resentfully that you've forgotten about altogether [for example, the evil Fairy Carabosse, left off the guest list for Aurora's christening party] and the way that at the peak of your bliss the enemy can be waiting to attack. The music is full of alarms -- all through, the most luxurious variation-music for the fairies has sudden outbursts of trumpets. But you should not get paranoid.

The ballet is really about faith and compassion. Many people say that there's no suspense: We know the outcome, she's not going to die. Well, they tell you things like this all the time: This operation is a piece of cake, you'll just go to sleep at 11 AM and you'll wake up at 1 with a knee that works again (or you name the procedure). Fact is, we don't know; the suspense is still there.

Isn't that a great explanation? Thank you, Paul!

So timing matters: you don't have suspense without the suspension of action. In Martins's Sleeping Beauty, one fairy is just completing her variation when the next barges in and waits in starting position for her turn. It's very distracting and makes you feel that the first should hurry up and finish. Couldn't we dwell for just a moment on each fairy's unique gift? After all, it's the combination of them that make Aurora beautiful straight through to her soul. And it makes the arrival of Carabosse the evil fairy more alarming.

And when Martins reduces the time for the hunting outing and the scary forest journey where Prince Desire hacks his way through the tangled Carabossian brush to get to Aurora's castle, the effect is to turn our hero into a spoiled brat. The prince gets whatever he wants as soon as he wants it. He doesn't feel like hanging out with his fellow aristocrats because he's in a lousy mood? Fine, they'll pack up their picnic baskets moments after they've settled down. He wants a princess to love? Not to worry, Lilac Fairy will deliver her so fast that we hardly register the kiss that brings her back to life after 100 years of slumber.

Why should I rejoice at their marriage when he's such a pig--and she's not so interesting either, as the gifts the fairies bestowed on her (serenity, courage, pluck, etc.) are a blur?

But critics and ballet forum posters didn't seem to mind any of this, engaging in the usual archaic ballet talk--about what each dancer brought to the pas. This is why it's refreshing to go to the ballet with people interested in other things. They immediately pick up on the holes in the story. I once took a friend to ABT's Swan Lake. After the first act, he said, Wait, that's the prince? The guy sitting in the corner? How are we supposed to care about him if he's sitting there the whole time? Exactly.

I think people worry that they'd be giving up the "classiness" of ballet if they admitted that coherence mattered. I think they should admit it matters.

PS. Apropos of ballet fans in odd places, I just got this email from my friend Andy Podell, a fantastic playwright. (He was in the Samuel French Off-Off-Broadway Short Play Festival this summer and blew the competition out of the water. I had begun to feel that the assignment, to put on such a short play, was impossible, and then his "Mom Was a Carney"--about a lovely lost soul hungry for donuts--came on and in a delicate and pillowy way dug to the heart of mother-loss sadness. In 20 minutes. Amazing. Anyway.... Andy writes):

Went to Jim Carroll's memorial next door at St. Mark's Church and it turns out that Carroll, oddly enough for a punk neo-Beat heroin addict, was a big ballet fan and was friends with and admired Edwin Denby. Ever read any of his dance criticism?

Yep, sure have. Besides being a dance critic--preeminent--he was also a poet, and had this to say about our beloved underground:

The subway flatters like the dope habit,

For a nickel extending peculiar space:

You dive from the street, holing like a rabbit,

Roar up a sewer with a millionaire's face.

To hear Denby himself read the whole of "The Subway" shortly before his death, at age 80, in 1983, click here.

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments