foot in mouth: December 2009 Archives

I found Reggie Wilson and Andreya Ouamba's dance, at BAM last week, maddening and, perhaps unwittingly, kinda rude. Its nonsensical combination of casualness and overweaning symbolism put pressure on the audience to get the work to cohere while also making us feeling silly for trying. Putting the audience in a bind is always a bad idea, I think, unless it's done with such wit that you have to forgive it for making a fool of you. By now, it's also become a postmodern commonplace. Time to try something else.

Here's the bulk of my review (and please click for the rest). Then I will complain some more!

Some dances are so airtight that they give you no room to think or feel. Other dances - usually on the postmodern and pedestrian end of the spectrum - are so loose-knit that whatever floats into your mind is soon replaced by something else equally random. The Good Dance - a much-anticipated choreographic collaboration between Reggie Wilson, from Brooklyn by way of Milwaukee and, once upon a time, the Mississippi Delta, and the Congolese Andréya Ouamba, now based in Dakar, Senegal - suffers from the second, spacey problem.

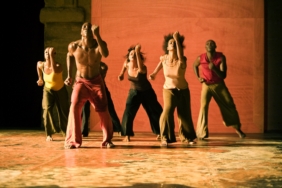

The Good Dance - dakar/brooklyn begins promisingly. Six of the work's nine captivating dancers line up - unsmiling, gazes level - as if for a mandatory class photo. Then they take turns introducing themselves in jagged solos that, with the help of Naoko Nagata's intriguingly patchwork outfits, bring out their individual idiosyncrasies. Tiny, pale Anna Schön's winging arms gather so much force that they nearly knock her on her back. Impish Fatou Cisse lands from her jumps as if stamping footprints in the mud.

Fatou Cisse. Photo: Antoine Tempe

But just as pattern and drama start to build - the ensemble skittering sideways with limbs sharply angled and brightening their flexed-footed jumps with an air of surprise - the lights come up, the afrobeat disco music dies, and Wilson walks on to lay down the show's concerns: the relationship between the choreographers' working methods; between the Congo and the Mississippi Delta, sites of both unimaginable suffering and immense cultural fruit; and between the Good Book of the western tradition and "the Good Dance" of African culture. Wilson delivers these enticing themes while clownishly balancing a water bottle on his head.

The water bottle shenanigans aren't, however, what convince me that The Good Dance will never get around to its subject. It's....

To find out what did convince me, click here.

So, about that overweaning symbolism combined with a casualness that resists symbol altogether, let's take those water bottles--hundreds of them, half-empty or half-full--in a dance that "investigates" the connection between the Congo river region and the Mississippi Delta. (God, I hate that academic investigate, which means not to look at the evidence and come to a conclusion, as in common usage, but to circle around and around the issues without feeling that arrival might be desirable). I think I get what the bottles are about: in place of free water (to wade in--as the gospel tune says-- or swim in or drink), we have contained water, paltry water, but also this shimmery, translucent object, which is an art object like this dance. You can see through it and it may leak out, but it isn't, doesn't want to be, the river itself. Okay, got it. And yet the dance needs to do more than present the bottles, play catch with them, rearrange them, and then forget about them. The piece needs to keep reinforcing what they might mean--perhaps our divorce from even the most essential aspects of life, one of which is our histories, and

Lately, people have wanted to make dances about what it's like to be haunted by something too tenuous for the body or even memory to hold onto. The topic favors writing, especially in a philosophical or theoretical vein. Dance has difficulty showing absence without either turning it into substance or making the dance itself seem not quite there. Which doesn't mean it isn't worth trying. Sometimes the best dances arise out of the most improbable prompts. You just need to address the difficulties without simply apologizing for them or passing them off on the audience.

About the other claim Wilson makes for the dance, that it is positing a Good Dance in place of the Good Book: it's a fine idea (as my father liked to say), that the logic or system of a dance or dance culture might have a moral base, but to invoke that moral edge by such puny means as one dancer knocking a bottle off another's head is to misunderstand poetic transference. When you use a part for the whole, the part has to feel momentous, or you diminish that whole--in this case, the Good Dance and by extension the Good Book.

Shall I complain some more? The music was a herky-jerky mix of traditional African drumming, gospel, blues, etc. The Good Dance doesn't dig in to the musical genres' likenesses and differences; it doesn't even pick tunes that would lend themselves to our doing so. It wouldn't have been so hard to take a tune and play out what happens to its beat as it crosses the Atlantic. For example, the heavy anchor that the blues, and much gospel, provides for its bass line the Congolese percussion either leaves out altogether or treats as a two-step, a dance step. It's so interesting, the solid downward slide of the blues versus the swift stream of African beats. And when there's guitar in African pop, its melody hovers above the bass line very sweetly like a cloud.

My favorite moment in the dance was co-choreographer Andreya Ouamba moving in his beautiful, rangey way in between the beats of--I think it was Aretha Franklin's "Precious Memories." And there, what all the talk couldn't tell us: one time signature moving inside another; Ouamba's light, swift, complexly accented beats inside the heavier, more staccato gospel.

I could have watched him all night. (I feel terrible that this is our introduction to him. Wilson has a track record here and will have other big chances, but Ouamba and his Dakar company, Premier Temps? Who knows.)

Okay, if you want to read the rest of the review now, you may.

The Good Dance is touring the West Coast, Arizona, Vermont and Connecticut in April; the choreographers have their work cut out for them.

Here, for your listening pleasure, a bit of Malian blues, which does in itself what Ouamba and the gospel he was dancing inside did together. Vieux Farka Toure's father, Ali Farka Toure, whose tune this is, was a big proponent of Pan-Africanism generally and specifically of the ongoing interplay between traditional African music and the American blues.

Here is my Alvin Ailey roundup of the season--after watching the three premieres and the 13 "best-of" tidbits and evening in honor of soon-to-retire Ailey artistic-director queen Judith Jamison.

I have the usual praise (for the dancers) and complaints (about the repertory) and then a plea all my own, which you will have to click for the whole article to glean. (Please click! I think my plan for the company is a good one!)

Here's the first part of the piece, published in the Financial Times this Saturday:

Judith Jamison's 20th anniversary as artistic director of Alvin Ailey is upon us, and no one will let us forget it. The company has reprised several of her works, offered a compilation of "best of" tidbits from pieces she has commissioned or revived during her tenure, and is visiting one city for every year of her reign on its upcoming US tour.

There's good reason now to pause exuberantly over Jamison's transformation of the troupe from popular yet shaky to world-renowned and rock-solid, with its budget quadrupled, its new Manhattan home eight storeys high and made of glass, stints before a television audience of millions, and sufficient funding for the national and worldwide tours that spread the Alvin gospel: Jamison is stepping down next year.

But at a point when "the name Alvin Ailey might as well be Coca-Cola", as the choreographer's schoolmate Carmen de Lavallade has ruefully put it, it's also worth asking what exactly this gospel consists of.

No one said at the subdued celebration for Jamison last Sunday night, which included short laudatory speeches and a slideshow in which she said "cheese" with President Obama, then Oprah Winfrey (the TV host got the louder applause). So I'll say it: the dancers. They embody - even improve upon - whatever they are handed. They combine astounding musical and muscular precision with a liquid softness down their spines and into their hips that keeps their virtuosity from becoming a shield to fend us off (though their mouths could use some relaxing). This season, the men - so elegantly long-limbed and sensually loose-hipped - have especially impressed. In fact, the company could end up like American Ballet Theatre if it's not careful, with choreographers rushing past the women to make ever more elaborate steps for the men.

A tilting diagonal of dancers, bedecked in costumiere Omotayo Wunmi Olaiya's variations on blue and white, in Ronald K. Brown's stupendous Dancing Spirit, by far the best of the Ailey premieres this year. (For those of you not in New York, I think it will be part of the upcoming U.S. tour.) Photo by Andrea Mohin via the New York Times.

Revelations is the other perennial good, though I wonder whether it has become like the Grand Canyon - such a national treasure that viewers see right past its craggy form. Ailey has heard in the spirituals that make up the score not only the joy of salvation but also the terror of sin. The speed with which the Sinner Men articulate their huge staccato steps and the statuesque solidity of the "Fix Me, Jesus" supplicant's final dovelike pose, for example, embody a welter of conflicting feelings: fear, aspiration, resolve. But audiences seem to read the dance's daylight conclusion in the bright Sunday sun after church into its midnight beginning. They make the dance easier to take.

The company needs to cultivate other great dances if only so Revelations, which has closed almost every show since its 1960 premiere, can be fully absorbed. Repertory is where the company's good news, and Jamison's miracle, ends. Ailey wanted dance to be "a popular form, wrenched from the hands of the elite", he explained in his autobiography, but by "popular" he meant Ellington, Mingus, Masekela, the blues and traditional gospel - not tiresome stereotypes, clichéd sentiments, threadbare steps and weak form. Even if he sometimes produced it himself, the man didn't want dreck.

This season's three premieres are typically uneven....

And for the whole thing, click here.

The company has a formula that works: great dancers, predictably "uplifting" dances, and then Revelations to keep its artistic cred intact. But why settle for being merely popular and sporadically great when you've got the goodwill of the world and could stand to stretch your audience--and be great through and through? I'm sure Mr. Ailey would have wanted that. Any self-respecting artist would.

Also, I don't mention Rennie Harris in the piece, but he's another choreographer, along with the mystery choreographer you will have to read the rest of the article to get the name of, whom Jamison hasn't done enough with. If you saw the ballet Harris made for Philadanco, Philadelphia Experiment, at the Joyce this spring you know what I mean. I'm salivating at the prospect of him doing something similar for Ailey.

Also, while I'm at it, I know the company has "American" in its name, but if they can do a European choreographer such as Bejart--the company performed his Firebird a couple of years ago--why not African choreographers? About six years ago, an outpouring of contemporary dance from southern and western Africa reached us, and I'm sure the artists are still working even if we're not getting to see them anymore. Maybe Ailey could commission a work from the Burkina Faso team of Salia and Seydou, if the choreographers are interested.

My Financial Times review of the choreographer's dance with Judith Sanchez Ruiz and a large white cube, going on right now! at the New Museum on the Bowery:

It is a truism that visual art favours dispassion, while theatre and dance, being live and peopled, stir up sentiment. But in Replica, by Jonah Bokaer - a luminous Cunningham dancer for eight years (beginning at the tender age of 18) and now a conceptually savvy choreographer - the pathos stems from a cube.The hour-long dance (repeating tonight and tomorrow at the New Museum and in Paris, Marseille and Moscow this spring) takes place on film and stage, sometimes at once. After Bokaer and Judith Sanchez Ruiz of the Trisha Brown company have stacked themselves on their sides like two undulating jigsaw pieces, a précis of the dance to come unfolds in grainy black-and-white film on a large, fissured white cube: set designer Daniel Arsham smashes a hole in a wall and the two lithe dancers crawl in, except the film runs backwards, so they seem to hatch from the hole and Arsham seems to be violently repairing it - a more hopeful tale. In real time, only the steps, not the drama, occasionally rewind, with Bokaer and Sanchez Ruiz dancing in bunched-up fashion like a mind plotting the route to a future it can imagine from a present it cannot.

Jonah Bokaer and Judith Sanchez Ruiz silhouetted against the fissured white cube. Photo by Michael Hart.

The choreography is a geometry of planes and angles. The movement emanates from highly articulate and independent joints - neck, shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, ankle. When Bokaer and Sanchez Ruiz dance close, they maintain this gawky precision. They don't move cheek to cheek so much as collarbone bumped against collarbone. They touch in places that spark no immediate associations: bony protuberance of hip, length of neck, just above the bulge of calf. "Does this count as tender?" you may wonder before remembering how rare it is for touch to be neutral.

But when the film returns.....

For the whole thing, click here.

P.S. Here's the whole of the last sentence, which was somewhat trimmed for space reasons (bold for trimmed part): "The meta-issues Replica plays with - art emerging from the white cube (of the art museum, nudge, nudge) into the black box of the theatre; dance busting out of its frame - seem inconsequential beside steps that are still singular but now also precious, like a love affair you'll never be able to make sense of to anyone except maybe yourself." I can't decide if I like it whole or if it's too much--too much explaining.

When a new director takes over a company that seems to have exhausted its reason for being, of course you hope he will lead it in a brave and bold new direction. That seems to be Eduardo Vilaro's plan, but he hasn't sufficiently taken the measure of his dancers nor made it possible for his elected choreographers to, so the results were decidedly mixed on Tuesday, opening night of the Joyce season, as I lay out in my Financial Times review:

This New York troupe doesn't really worry about the hispanico moniker. Founder Tina Ramirez, who retired last year after four decades as artistic director, required only that choreographers choose Latin music, which somehow led to Broadway razzle-dazzle as much as anything else. For his inaugural season, the 45-year-old Eduardo Vilaro - recently director of Chicago's Luna Negra Dance Theater - has commissioned work from Latino choreographers, then let them do what they will. The result is a brave mess.

Perhaps Ron De Jesus counted on the original score by Oscar Hernandez, Ruben Blades' regular arranger, to lead the way only to find his species of Latin jazz too light. "Triptico" begins as a sombre, smooth romance, with couples swirling around each other in deconstructed ballroom moves, before veering off into a romp, with each woman using her man as ballast to sail through the air like a kid cannonballing into a lake. "Triptico" may not cohere, but it does showcase the dancers' pleasing plushness and good cheer.

Jessica Batten slicing through the air with her rapier legs, supported by Waldemar Quiñones-Villanueva and Nicholas Villenueve. Photo by Rosalie O'Connor for Ballet Hispanico.

Belgian-Colombian Annabelle Lopez Ochoa has no trouble nailing down her theme, which as far as New Yorkers have seen is always the same: dank and doomy relationships......

For the whole thing, click here.

Vilaro doesn't seem to be moving in this direction, but it would be neat if in the future the choreographers were a musical bunch, besides being Latino. Tina Ramirez required her choreographers to use Latin music, but not to know what to do with it. So much Latin music is dance music, which is fantastic until you bury its rhythms under a 4/4 beat. Then it's excruciating.

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments