foot in mouth: July 2009 Archives

The first time I saw the company, with him still dancing strong, I was 14, it was 1978, and there, at Zellerbach in Berkeley --Sounddance. I leaned so far forward in my seat--drawn into the vortex of the dance--that I fell on the floor.

On paper, in description, Cunningham's kind of dance wasn't what I thought would move me. I was a repressedly moony teenager--the kind of girl who reads Sons and Lovers and can't understand why Paul prefers translucent Clara to the gloomy, entangling succulent, Miriam. But it did move me, more than almost anything else--and has done for 30 years. That's the sign of genius--to make a person alive to something that wasn't even in her. He changed me.

Every time I've shown up, I've wondered, Will the spell have worn off? Will the dance become what I've always anticipated it would be: cerebral and faraway? And every time, there it startlingly is.

Click for Alastair Macaulay's fascinating obit (did you know Cunningham started at Cornish as a theater major?) and here for a lovely video tribute (with clips from a few dances).

The New Yorker is also offering a bounty of archived articles and reviews--by Joan Acocella, Calvin Tomkins, Alma Guillermoprieto--on its website, some of which are available to anyone and some of which you need a subscription for. If you have a print subscription, they tell me, you can sign up for the electronica free here.

UPDATE: Guillermoprieto posts a short, very poignant remembrance of a Cunningham birthday party, with organic cake on paper plates, in his shabby loft.

First, a few facts: New York City Ballet's Peter Martins is making about $629,000 a year

while 11 corps members are cut.

The original Bloomberg article from which the Times quotes listed other exorbitant salaries--music director Faycal Karoui, around $300,000; general manager Ken Tabachnick, about the same; etc.--but this only proves that the writer knows nothing about the arts or is afraid to admit what he knows, because the company isn't the general manager's or the music director's baby the way it presumably is its balletmaster's, so of course they have to be paid competitively. The article also mentions the 2008 income of outgoing dancer Damian

Woetzel, a 23-year-veteran of the company: $278,000, of which $66,000

was exit pay. Also, irrelevant: A ballet dancer's career is over at about age 40, and if it's at all possible

to give her a cushion to prepare for a second act, it should be done.

Martins isn't in that situation.

As the Baryshnikov example makes clear, Martins is basically paying himself--with the NYCB board's approval. And what's the worry on the part of the board? That if he isn't paid like a king, he's going to work for the competition? See? Comparisons to directors outside the arts don't work. But if Martins is in fact thinking about it that way-- if the money's what's keeping him--let him go. These are bad values for a ballet company to be burdened with.

So I debated whether to link to my latest review for The Financial Times--on the Emanuel Gat company, at the Lincoln Center Festival--because I may have bungled it (not for lack of trying, believe me). But perhaps you could click on the link and NOT read the review (dance never gets enough clicks)--and maybe, once explained, the bungles will make an instructive story--you know, for all of you hoping to make your fortunes as dance writers.

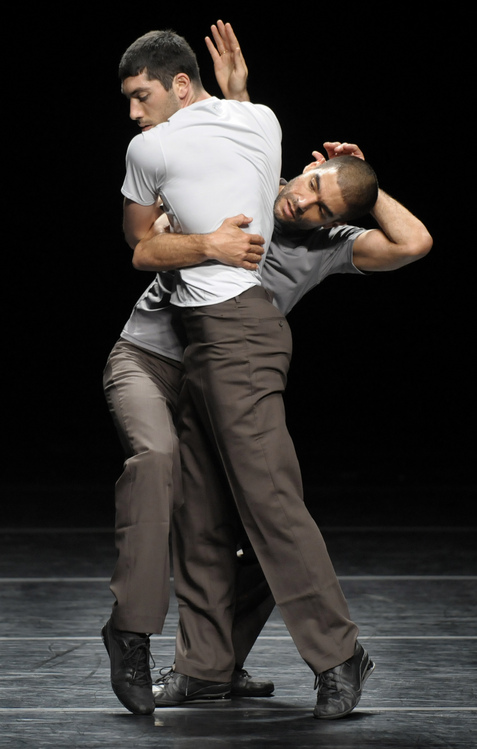

The glorious Assaf (in white T-shirt) and Gat. Photo by Sara D. Davis courtesy of ADF/2009

The piece was hard to write because I had a big idea and couldn't decide how much of it to get into in a 400-word review. A review is not exegesis--not what we did in college--except insofar as the dance's "about" reveals the experience of watching it. And yet so often it does. In fact, I'm not sure how you can decide what a work of art is worth if you don't have in mind what it's doing and meaning. In this case, though, it was only by a series of analogies that I understood what it (the first dance on the program, at least: Winter Variations) stirred in me. Gat presents something invisible--two people thinking together--in visible form in order to mirror the difficulty and magic of that mental communion. I'm not sure I gestured toward that chain of equivalencies, which made the dance feel deep and far away, without getting entangled in it.

Next time...

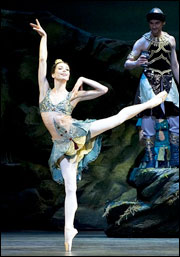

For Los Angelenos trying to decide which American Ballet Theatre cast next week: the thing about Macmillan's ballet, like the play, is that it's the pair that counts. Half a pair of lovers amounts to none at all--and these two are fantastic together.

Photo by Rosalie O'Connor

Hallberg is a swift stream of impulse and warmth; Murphy is one of the only ballerinas today exploring a domain of femininity that I recognize, that feels familiar more than mythic, and all the more beautiful for it. Male dancers have been changing character--not just steps--for the last few decades, but women have incrementally lost character--and then been told (by critics if not coaches) to look to precedent. Murphy's characters and the musicality and silent-star animation by which she conceives them do something new. For example, when she first meets Romeo, she looks at him with so direct a gaze--so unpracticed in the art of coquetry, unburdened by the commonplaces of love--it borders on impudent. And when, not much later, she's overtaken by feeling, it's like a blush rising through her whole torso through the crown of her head. You can feel the heat rising. Often with Romeos and Juliets, one feels that they love better than we ever could. Murphy makes the love exceptional but also recognizable and thus we love her more--and are more wretched at her death.

Her Juliet allows Hallberg to be more interesting too--softer, more exposed at heart, without ever being effete or princely. (My friend Carlene said, "I don't think I've ever seen a romantic male dancer," and I know what she means: men are so often playing the courtier that it's not always clear if you're watching the expression of the character's heart or merely good manners.) These two often dance together, but this is their most symbiotic relationship, as it should be, given the story.

They play the lovers young, which might have been cloying but instead felt as if the romantic gauze that usually wraps the ballet were stripped away so we could peer straight back (if we happen to be beyond youth ourselves--there were a lot of enrapt children in the matinee audience) to when huge things were happening around and inside us and we had to invent out of nothing the resources to respond.

Carlene and I cried at the end, and when the curtain fell, this audience full of mothers and their tween daughters (in gloriously mixed ensembles, such as one girl in owlish glasses, t-shirt, sparkly ballerina skirt, and sneakers. Yay!) rushed to the front to applaud. If I were a parent, this is the pair I'd bring my child to.

I review her debut as Sylvia for the Financial Times.

In the cave with ogre Jared Matthews. (He might have bit into the part with more appetite: would have helped Vishneva's comic turn.) Photo by Gene Schiavone for ABT.

It's really a delightful ballet--the delicious Delibes score as mercurial as the deus ex machina plot, sliding from trumpeting horns for huntress Sylvia and her cadre to lyric love passages to sensuous harem music to the buzzy sound of the villagers to the plucky violins for the ultimately princesslike Sylvia at her nuptials. It clearly influenced Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty (and some of the Candyland divertissements in the Nutcracker). In 1877, shortly after completing Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky wrote a friend,

Listened to the Leo Delibes' ballet Sylvia. In fact, I actually listened, because it is the first ballet where the music constitutes not only the main but the only interest. What charm, what elegance, what richness of melody, rhythm, harmony. I was ashamed. If I had known this music early then, of course, I would not have written Swan Lake.

Good thing he didn't. Anyway, Ashton responds acutely to Delibes, and his steps are so interesting in their back and forth balances (thinking of love perhaps, he treats the body as a pendulum: the dancer stays on balance by way of counterbalances), which Vishneva brings out.

I know Ashton felt burdened by all the ensemble choreography he had to foment, but what he came up with is ingenious and exhilarating: for example, the staglike movements for the huntresses (resembling the creatures they hunt); the pinwheel arms and stalwart feet for the columns of villagers and gods (all mixed up together) in the final act; and the odd "marking" entrechats of the villagers' circle and line dances--it's such a peculiar and ingenious way to suggest folk dance, which is often marked so that old and young can keep it up for a long time.

I don't talk about all this in the review because the news this year was that Vishneva was taking on the role. I do mention that the steps are less visible--less well articulated--than in past years. But they're still good enough to make the ballet worthwhile, particularly if you've never seen it.

Vishneva does it again tonight, then Paloma Herrera tomorrow matinee, and that's it for Sylvia this year. People have liked Herrera in this role, though the one time I saw her she seemed only intermittently engaged--flickering in and out of focus. But that's the thing about Herrera: you never know when she's going to be thoroughly involved. (Actually, you kinda know: generally, it's Balanchine and contemporary works.)

My friend, playwright Andy Podell went to see the ballet for the first time and writes with enviable insight [my interpolations in brackets like this]:

Great review. I basically agree, but it's the first time I saw Sylvia and I was pretty much in heaven. The first act and the entrance of Vishneva and the Delibes music made me shiver. Also the ending of the first act is beautiful... lovely... I loved the way Eros points the direction to Aminta after returning his life.

It's a very pagan ballet. The opening sequence is the erotic play of the elements of water and trees or wind [and fauns, swinging each other around and then settling in a little love bundle with the naiads (or perhaps it was the dryads)]. Later the two sheep are kind of intruding into the Classical world to keep us reminded that love has its animal level (even though they're a pretty cutsey-poo duo) [in case the bronze sculpture of Eros, carried overhead with great comic solemnity, doesn't!] So the ballet has a coherence to me, but it's a kind of masque drama--The Triumph of Eros--and Sylvia and Aminta are really just another duo like Pluto and Persephone. There's no arc of character, as you said.

I really liked the two slaves in the harem sequence. I don't know what their names were [Arron Scott and Grant DeLong] but they were fantastic clowns--really subtle and sexy clowns. It tickled me how the heavy was this Muslim/Turk/terrorist who kidnaps the girl from the Western civilization.

d

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments