foot in mouth: November 2008 Archives

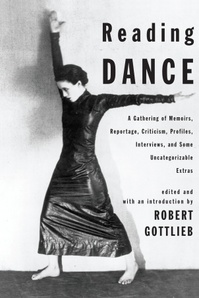

If you've been reading Foot this week, you know I was dismayed to find that the "Dance" that "Reading Dance" offered wasn't as comprehensive or as timely as an anthology of this size--1,300-odd pages--would warrant.

But on second thought (says our lady of second thoughts), if you just disregard the title and reorganize the contents, there turns out to be a good book inside the dubious one.

The good book has largely to do with ballet's efflorescence from the '40s through the '70s--mainly in New York, secondarily in London--and the Russian antecedents to that renaissance, from Petipa through Diaghilev.

For me, the heart of that good book is the Balanchine material, possibly because it's where Gottlieb's deepest knowledge lies, where he can go beyond the usual suspects.

Some favorite items:

--Suzanne Farrell talking to David Daniel in the late '70s about dancing with Balanchine

--Diana Adams talking to David Daniel about her surprise and misgivings upon first encountering Suzanne when she was still Roberta Sue, and about what she was like subsequently onstage, in rehearsal, and in class. The pairing of these two interviews, both from Ballet Review, is fantastic.

--Antoinette Sibley on "Swan Lake." I was going to quote a bit from it, but after 20 minutes trying to relocate the piece, I give up.

Which brings me to another problem: the organization. Gottlieb has created sections more by writing genre than by writing subject. So, the interviews are in one place while the reviews of ballets that the interview subjects danced in are somewhere else. Generally people who want to read about, say, the Royal Ballet don't care if it's an essay or a commentary, they want to read everything they can find.

To have a subject scattered hither and yon is maddening.

Of course, how you organize it depends on who you think is going to read it. And Gottlieb seems to think he is aiming at dance beginners. I don't think he actually is. If you haven't ever seen "Swan Lake," Sibley describing her pleasure dancing Odile--the lust-power of the courtesan it evokes for her--won't be particularly though-provoking because you won't have any Odiles in mind. If you've never been thrilled by Suzanne Farrell arcing backwards in the adagio of "Symphony in C," her description of how she creates that effect and why she has kept it won't mean very much. If publisher Pantheon had gone the multimedia route and included a DVD with video excerpts of Farrell (there is a good deal of Farrell on film) and others, laypeople might be more attracted to the book.

But in its current incarnation--not for beginners and not for people under a certain age--I wonder about the inclusion of excerpts from easy-to-find books, such as Alexandra Danilova's autobiography, Lincoln Kirstein's essay collections, Edwin Denby, Arlene Croce. I may not be exactly typical, but I think I've read about a third of the offerings in their original form. On the other hand, if the scope had been narrowed, then Gottlieb could have offered Croce on Farrell in "Symphony in C," Denby on the first "Symphony in C," and it would have been great to flip to them after the Farrell interview.

Alright, that's all I'll say on the book. See for yourselves.

What a bright soul.

I didn't know Clive Barnes, but we smiled--he with his lovely wife, Valerie--whenever we encountered each other on the aisle, and I always read his reviews in the New York Post and his columns in Dance Magazine with delight.

He was old without ever being an old fart. Curious, never immune to enthusiasm, but no pollyanna either, he gave me faith that even a review of a couple of paragraphs could be worth the effort. Here's one of those paragraphs, about Christopher Wheeldon's "Within the Golden Hour" for the San Francisco Ballet:

The whole impression is of beautiful creatures at artless play. The choreography is brilliant but unforced, with the dancing so spontaneous that they seem like co-conspirators rather than simple performers. It's a delightful work, revealing Wheeldon at his best.

Written just weeks ago, when Barnes must have been in terrible pain.

And about Damian Woetzel at his farewell performance for New York City Ballet this spring:

Woetzel was simply magnificent, both as the cheeky World War II sailor on shore leave, then as the penitent prodigal seeking his father's forgiving embrace. He takes his leave at the peak of his form -- that perfect crossover mark between physical possibilities and artistic maturity.

Clive Barnes seemed always at the peak of his form.

He'll be much missed.

It was a labor of love: there would be no other reason to spend a decade sifting through thousands of pages of previously published work for this massive "gathering of memoirs, reportage, criticism, profiles, interviews, and some uncategorizable extras," as the subtitle puts it, in charming 18th century fashion. I was excited to discover the 1360-page tome in the slush pile at the women's magazine where I copyedit, and drag it back to my lair for a good look. But it only took the table of contents to change happy anticipation into despondency.

Gottlieb is one of the few people associated with dance who have the credentials to get such a primer into print--not because of his dance writing (dance never carries that much weight), though he did write a lovely biography of Balanchine, but because he has been the editor of Knopf and The New Yorker, so people in the publishing industry trust him.

Maybe they shouldn't have.

You can offer an anthology mainly looking to the past, but the whole project becomes an exercise in nostalgia, a mausoleum, if you don't create some bridge to the future. "Reading Dance" doesn't. There is Astaire but no Savion Glover--and nothing about the Astaire to get you to Glover. There's Tudor but no Forsythe, not to mention Wheeldon (though there is Boris Eifman--why? Just because it's fun to hate?). The ballet dancers basically stop with the generation of Gelsey Kirkland and Baryshnikov--there's no one with the contemporary sensibility of Wendy Whelan, Diana Vishneva, or Gillian Murphy. The modern dance is focused on Graham, Taylor, Cunningham, with a smattering of Judson-era noodlers, and ends with Morris. It's as if the last few decades never happened.

Gottlieb may feel that indeed nothing noteworthy has happened since Reagan, but then he should have taken the advice of unlike-minded friends (if he has any: from the looks of the acknowledgements and contributors, perhaps not). He should have been leery of a generation's narcissism.

And he should have been braver: there's not one risky subject in the book.

I wouldn't have been so disappointed had the title prepared me--if instead of "Reading Dance," the book had been called something more modest and more accurate, like, "Reading Dances I Have Loved and Looked to," with the subtitle modified to "A gathering of memoirs, reportage, criticism, profiles, interviews, and some uncategorizable extras by the Boomers, the dead, and a few in between."

But see for yourself--"Reading Dance" is now in bookstores.

And let me know what you think.

UPDATE: If you disregard the title and the ambition of the book, and reorganize the contents, you will find a valuable history inside. I explain here.

In dance, and even moreso in the subset of ballet, we don't possess such a supply of geniuses that we can afford to demote any of them to the merely good, or even to era-specific genius. So between the video testimonies that Baryshnikov, Agnes de Mille, and director Kevin McKenzie proffered to the soothsaying powers of Antony Tudor at American Ballet Theatre's celebration in his honor a couple of Fridays ago, I felt a dread coming on.

The centennial commemoration at City Center began with "Continuo," which Tudor made in 1977 for his students at Juilliard, where he taught for decades. The piece is unusually cheery and plotless for him--in its standout moment, women dive like dolphins (rather than the usual fish) into men's arms, who take their momentum, and their bodies, and run with them. Still, it reminded me of what an inarticulate oddity of steps Tudor can conjure: arms and legs bent as if made of wood, deliberately modest turnout, a paucity of plié--in short, a stubborn refusal to embrace the elasticity, expansiveness, and uplift of ballet.

Tudor siphoned steps through dramatic

imperative. The legs are quasi turned out because the story is inward--about

hearts that can't be exposed without being lost (along with heads). Joints are

stiff because the force of the characters' romantic and libidinous feeling

catches in their crooks. Plus, there's the lure of symbolism: Tudor wanted

steps to read symbolically; he wanted gesture to inch toward archetype. Along

with mid-century dramatists Martha Graham, Eugene O'Neill, and Tennessee

Williams, the British émigré brought epic proportion to the particular.

Tudor's rhythms,

however, are dancey: a rush and suspend, rush and suspend, like waves that

reach a peak without ever cresting. The artfulness of Tudor's musicality has

the paradoxical effect of reinforcing rather than undercutting the ballets'

psychological realism. The rhythm is perfect for the conundrum that the

choreographer regularly returns to: feeling so bottled up, it's like a pillar

of fire.

Now that the

dances have outlived him, though, the rush-and-suspend rhythm has evened out

and the unwieldiness of the steps threatens to overwhelm their sense. That's

what happened at the centennial, anyway, with "Continuo" and Xiomara

Reyes and Gennadi Saveliev's dully dutiful bedroom scene from "Romeo and

Juliet." It's what prompted my dread. Once the physical awkwardness seeps

into our sense of the drama, Tudor's ballets come to seem quaint.

The most

frequent nominee for the musty-dusty award is "Pillar of Fire," about

three Edwardian-age sisters--a coltish flirt, all flyaway ribbons and waltzes;

Hagar, a starkly miserable virgin intent on self-immolation; and the stern,

washed-out eldest--and what happens when the middle sister "lets herself

go." Since repression no longer exists, not even among those who advocate

it (see: Bristol and the evangelical Right), it's not surprising that

"Pillar" would sink to period-piece status.

That it hasn't--that

it certainly didn't on this occasion--redeems Tudor for me, more even than

ABT's admirable performances of "Lilac Garden." (Generally touted as

his greatest ballet, "Lilac Garden" traffics in sentiments more

wedded to its outdated plot than "Pillar's" are, it seems to me.)

Murphy has cornered the market on repressed heroines. Last year, she brought out the comico-tragic gruesomeness of Lizzy Borden in Agnes de Mille's "Fall River Legend" (another ballet that critics regularly designate for storage). And she's been a persuasive Hagar for several seasons now. But on Halloween, she topped herself.

Because ballerinas are rewarded for their

vanity, they often get stuck at pretty. That's never been a problem for the

very lovely Murphy. She gives herself over to a role even to the point of

spiritual ugliness, or obtuseness, at least. (Earlier in her career, it was

more often comic ridiculousness: one of the few reasons to attend ABT's

"Raymonda" was to watch Murphy play a girl who's being courted right

and left, by good prince and bad, when all she really wants is to frolic with

her girlfriends.)

Her Hagar isn't someone we know better than Hagar herself does. We are not thinking, If only she could see how pretty and likeable she is. We suffer her cramped, explosive self along with her. She doesn't let us pity ourselves in the guise of her. ("I too am good enough, and smart enough, and people would like me--if they weren't such fools!") She is not "a girl with a bad self-image and a longing for acceptance," as Danceviewtimes' Gay Morris has asserted. (With a ballet like that, who needs self-help books?) This Hagar has given up on acceptance before the story even begins.

She is obstinate in her suffering. She

wears it like a crown of thorns, with the blood pouring down her face all day

and dripping onto the carpet. We've all encountered the type--in jobs, usually,

because if you could avoid this kind of person, you would. She is the most

visible of invisibles--glowing with the knowledge that she will have been

abandoned.

That's her tense: will have been.

She skips over the dubious present to live in a future perfect she knows will

be wretched. It's as good as done already. You feel bad that you don't like her, then resent her for that, too. Soon you have descended into a mise en abime of guilt and self-loathing. (Some feelings are contagious.) You wish she'd do something vile finally so you could off-load some of this evil feeling back onto her.

Marcelo Gomes as the Young Man from the House Opposite and Gillian Murphy as Hagar. (Photo by Andrea Mohin for the New York Times)

Hagar does, of course: she sleeps with the Young Man from the [Whore]House Opposite (no question, Tudor's names are quaint), and she gets pregnant, which is where the drama would lose us if Murphy hadn't so powerfully established the nature of the person we're embroiled in. The act's shamefulness may be outdated, but not the character of the shame. When Murphy's Hagar turns to the questionable young man, she is wanting nothing so humanizing as acceptance or love. Rather, her desire is made of the same elemental force as her shame. In that regard, she is like her deflowerer. It doesn't matter who does the deed, it only matters that he do it: liberate her.

He doesn't, really--because she already knows he won't. Murphy causes us to ache at both Hagar's restraint and the stiff force of her abandon. Critics often talk about Murphy's technique as if it had nothing to do with her dramatic power. But here, for example, she gives the steps the precision and force they need and simultaneously lets you feel what she has withheld--that there is a pillar of fire burning her up from within. The equilibrium Murphy establishes is wrenching--and true to Tudor.

What my colleague Christopher Caines says about "Lilac Garden" in Robert Gottlieb's new anthology, "Reading Dance," applies, with some modification, to "Pillar of Fire" too:

[The dance is] about things that don't happen.... It is a sign of Tudor's peculiar genius, his originality, and his wild courage that the ballet is built around a void.

In "Pillar of Fire" a lot does happen--our heroine gets knocked up, humiliated, then betrothed--but the characters' stillness, not their movement, defines them. Gomes's amoral Young Man maintains an oily equanimity without a single extraneous move: he takes whomever he wants without any resistance, in himself or them. Hallberg's Friend is like a cool stream jetting into a churned up river. He belongs in this town among these people--he is made of the same stuff--but what he has made of that stuff is unlike them. Whenever he appears, there's a suddenness and surprise to his arrival. And when he holds Hagar, he doesn't waver--Tudor distinguishes his steadfastness from her stiffness or the Young Man's easy brutality, though all are species of containment. And finally, Hagar is a maelstrom of the unrealized and the already realized. Until the Friend demands that she accept his help and solace, there is for her no present in which to rest.

I've seen "Pillar of Fire"

several times, but on Halloween I forgot the ending--that the Friend would come

to Hagar's rescue. When the lights lowered for a set change, I thought the

ballet was over, and I felt relieved. If Hagar had been smaller in her inchoate

desire and more likeable--less dumbly mute and stalwart in her terror, less

epically doomed--it would have been easier to feel bad over her abandonment by

the bordello man and the town. And I would have felt less. As it was, my

feelings for her weren't at first so different from the townspeople's. I didn't

entirely want to be drawn in to her struggle. So when I was, it was akin to the

sex Hagar has: it involved too much force. When the lights came back on and the

ballet resumed, I thought, Please end. Hagar's self-consuming strength

is the particular provenance of women--even now, when we can sleep with whomever

we want whenever we want.

The "Pillar of Fire" that Murphy ignited is less about an innocent early-20th-century woman being condemned and redeemed than about a life as heavy as stone rolling inexorably downward. Unless there's an obstacle in its way--a tree, a Friend--it will keep rolling until it hits bottom.

That story has no sell-by date.

our new First Family.

our new First Family. I'd been calculating and recalculating the electoral votes since the beginning of October--you know, switching a NH for a CO, a Michigan for a Pennsylvania, etc., etc.,--and maybe by Monday, I'd arrived at a glimmer of hope: perhaps he could pull off 280 electoral votes. (Please, please.) But after the election of Bush for a second term--after it had turned out the President had lied about WMDs (not that even the lie was reason to invade) and Abu Ghraib had been exposed--I lost all faith.

And I thought the country was too racist to elect a black man.

God, what a joy to be found out wrong.

And did you notice, in Obama's victory speech, how he invoked Martin Luther King Jr.'s Moses on the Mountain speech, his last speech, as if Obama understood he was going to carry on from where King left off?

Here's King:

We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

And here's Obama:

The road ahead will be long. Our climb will be steep. We may not get there in one year or even one term, but America--I have never been more hopeful than I am tonight that we will get there. I promise you--we as a people will get there.

Choked me up.

Finally.

[Here's a video recording of the last minute of King's prophetic speech. And here's Obama's echo and tribute, in the first 30 seconds, here.]

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments