foot in mouth: April 2008 Archives

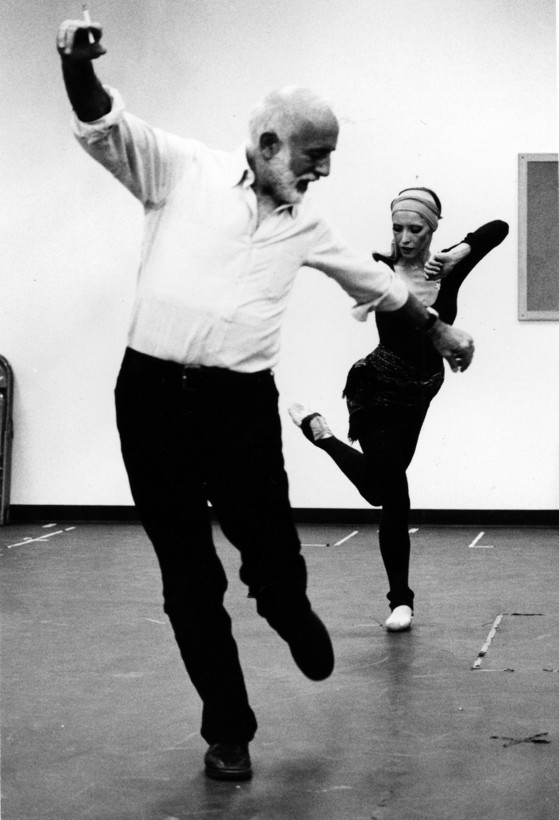

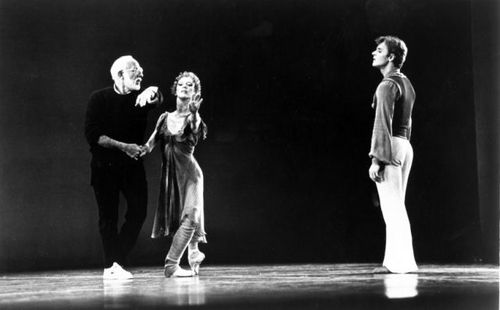

Natalia Makarova rehearsing "Other Dances" with Jerome Robbins for "Dance in America." The NYC Ballet fetes Robbins' work through June 29. (Photo by Brownie Harris for WNET/13, 1980.)

Here's my tiny story for Newsday on the huge Robbins Celebration at New York City Ballet, followed by Q&As with Baryshnikov and City Ballet principals Damian Woetzel and Wendy Whelan that didn't make the cut. (Imagine an enormous sidebar!) All of the dances discussed in the story and the Q&As are part of the festival, which begins Tuesday.

The black and white photos are by Brownie Harris for WNET, the colors by Paul Kolnik for New York City Ballet.

BY APOLLINAIRE SCHERR

Special to Newsday

"To make a decision, he was torturing everyone else and himself until the very last second," says Mikhail Baryshnikov of his friend Jerome Robbins. "Which means there was probably no better choreographer in the history of Broadway."

The quick-witted, neurotic New Yorker may be most famous for "West Side Story" and "Fiddler on the Roof," but he was wowing Broadway audiences--and producers--as early as 1944, at age 26, with "On the Town."

"Then he decides he wants to choreograph for women on pointe," explains Baryshnikov.

Enraptured by the New York City Ballet's debut performance in 1948, Robbins wrote its director, George Balanchine, "I'll come as anything you want. I can perform, I can choreograph."

"Come," was Balanchine's response. Robbins spent most of the rest of his life shuttling between Broadway and ballet.

On the tenth anniversary of his death, New York City Ballet celebrates Robbins with a whopping 33 ballets on 10 distinct programs through June.

Many of the dances--the social comedies "Fancy Free" and "The Concert," for example, and the sensual fantasy "Afternoon of a Faun"-- are plainly the product of a theater mind. For these, the choreographer focused on mood, says Damian Woetzel, whom Robbins--with his unerring eye for talent--plucked from the City Ballet school in 1984.

When Woetzel--whose two decades of unforced virtuosity end in a final burst of major Robbins roles this season-- learned the role of Riff in "West Side Story Suite," "Jerry thought I looked a little too ready to fight when the curtain comes up. He said, 'You're confident, so of course you're ready to fight, but you're not already fighting.' "

Even when the ballet had no story and dramatic intent wasn't an issue, Robbins demanded "the opposite of a jewelry-box dancer," explains City Ballet's extraordinary Wendy Whelan, who says she owes her "bit of authenticity" to the many hours spent in the studio with Robbins early in her career.

"In 'Brandenberg,' " the 1997 Bach epic, "you feel like a kid--scurrying and running and skipping and playing games," she says. And "Brahms/Handel," a collaboration with Twyla Tharp, "is a conversation between the two of them--and they really like each other. His lines are very clear, and hers are tweaked and curved. The dance weaves between them."

But in both ballets--in nearly every Robbins ballet--"it's about looking at each other, relating to each other, being down-to-earth," says Whelan.

"Jerry didn't want it to look like you were out there giving a show," Woetzel says. "And isn't that ironic--because he was such a great showman."

WHEN&WHERE New York City Ballet's Jerome Robbins Celebration runs through June 29 at the State Theater, Lincoln Center. Tickets $12 to $98. Call 212-870-5570 or visit nycballet.com.

Q&As

MIKHAIL BARYSHNIKOV, for whom Robbins choreographed "Other Dances" with fellow Russian émigré Natalia Makarova for a 1976 gala. When Baryshnikov went to City Ballet in 1978, Robbins made major roles for him in "The Four Seasons" and "Opus 19/The Dreamer." Later he created "A Suite of Dances" for Baryshnikov for the White Oak project. All of these works will be performed this season at City Ballet.

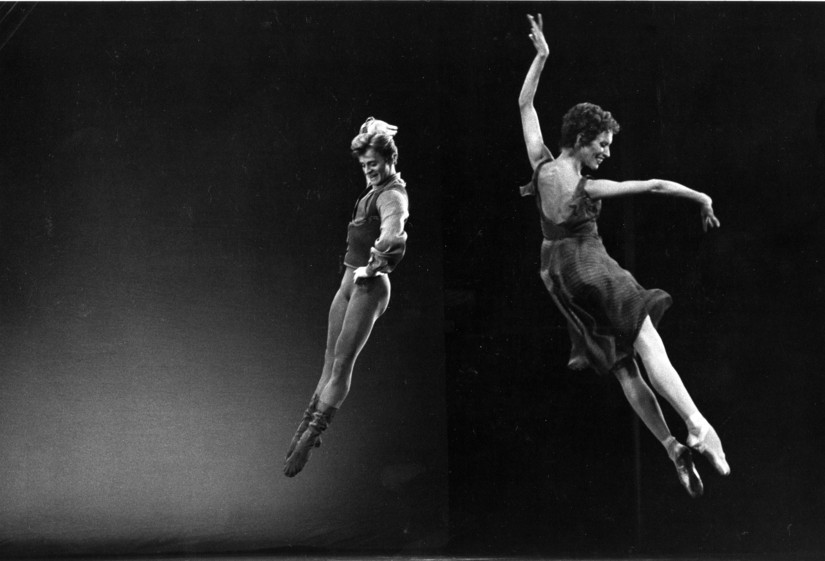

Baryshnikov doing his Slavic thing in "Other Dances" (Photo courtesy of WNET/13, by Brownie Harris. 1980)

How did you know Robbins?

We were friendly before we worked together. We had mutual friends and I was

very flattered that he came to see me dance at Ballet Theatre, and we had a few

dinners. And of course for the gala for the public library [where "Other Dances" premiered in 1976] Genia Doll [who paid for the dance] was a dancer in Ballets Russes and married to Leonide Massine, and had a salon in New York--her husband was a wealthy French man, and they had a house near Jerry's house in Long Island. And we spent a lot of time together either in her place on Fifth Avenue or in the Hamptons. I was really proud that I can be Jerry's friend. Totally starstruck.

Do you think he was starstruck over you?

I didn't give a damn what he cared about me! This guy choreographed "Fiddler on the Roof" and "West Side Story"!

Did you know about him in the Soviet Union?

I was 26 years old when I came here. I'd seen the movie of "West Side Story" and I saw New York City Ballet in 1972 in Leningrad. I knew not just of him, but his work already--in small doses, I must admit.

What was he like socially?

He was very funny, he was a very good storyteller.

Okay, "Other Dances."

The whole thing about "Other Dances" was he didn't want people confusing it with "Dances at a Gathering." "Other Dances" is not, "Yes, Virginia, another piano ballet on Chopin's music," you know what I mean. "Dances at a Gathering" was a community piece and very earthy and very gestural. And in its intent, when Eddie Villella [the originator of the boy in brown, the first dancer onstage] kneels and touches the ground, it's very emotional inside somehow. It is a slice of communal belonging. While "Other Dances" is a pas de deux and utterly Slavic, you know. Because of the fascination with Natasha's arms.

You're Slavic.

Yes, it's true, but it's very much about her. The people whom Jerry admired, he really, truly admired. He adored Natasha Makarova for the way she moved, the way she moved her arms--he was totally fascinated. At rehearsals, she was very flirty with him and very upfront, and he loved that. He loved to be tenderly abused.

She never had a very good memory

from rehearsal to rehearsal. She was kind of improvising all the time, and

Jerry loved that too, but he'd say, "Well, yesterday I saw you do

this." And she'd say, "Well, today is a different day, Jerry."

It was sort of a comedy routine with Natasha. It was sweet to see them play

like two kids.

And you just sat there and watched?

Yes, of course, and I'd be doubling for him. He was usually trying to do the steps full out. Sometimes I say, "Jerry, stop it. You'll kill yourself."

Jerry and Natasha have all the fun while Misha looks on.

What kind of a dancer was he?

He was a great character dancer, you could see it. And, remember, he was one of the best interpreters of Petrushka--the most fascinating and deep and tragic. People who worked with him at that time said so. [Robbins returned the compliment, saying of Baryshnikov's Petrushka at ABT, "[I] very gratefully gave him my invisible cape that

said on it The Petroushka."]

And in "Other Dances" he uses mazurka and the stamping and the arms absolutely from character dancing. In a way, "Dances at a Gathering" is a pure neoclassical piece, even though there's the epaulement and the Polish arms. Here, because we are both Russian and we did those steps from our childhood, it was utterly Slavic in nature. When I start to dance this with [New York City Ballet dancer] Patricia McBride she interpreted it as Jerry's dancer, she knew his choreography. It was a totally different sentiment; she was wonderful dancer, you know, but it was definitely a different color.

Do you think he was nostalgic about Russia/Poland--wished he had an Imperial background or was closer to his

own roots in Poland?

Of course, because he was a great character dancer, he admired, growing up, people like Leonide Massine, Irina Baronova--the old Russians--because they were part of history. Jerry just admired the spirit of those people.

I remember I talked to Boris Aronson, a famous designer--he designed my "Nutcracker"-- and he said about "Fiddler on the Roof," "The dance with the bottles on their heads, it's such a nonsense. Jews would never do that. And yet, how correct it is! How theatrically ingenious." That's the biggest compliment from an old timer like that.

You know when you're doing those mazurka head waggles [in the 1980 Dance in America film of "Other Dances"] and you're shaking your head like a madman--was that your idea?

No, no, no. On my end, I never improvised. It was Jerry. In fact there are some photographs of Jerry in rehearsal flicking his wrist and turning around. It was very much Jerry. I could see him, in rehearsals, wearing sneakers and the velvet jeans and that Slavic shirt--you know, without the collar. And that's where the costume came

from. He always got into this folk element with all his heart.

[About the dance's last section] I told him that when Balanchine came to Russia, a journalist said, "Oh, Mr. Balanchine, Tchaikovsky's Serenade--it's just impossible to imagine another piece of choreography to this music." And Balanchine said, "Nonsense. I could do two more ballets, and maybe even better than this one." I told Jerry this and he laughed. He never heard this story. He first choreographed my dance and then he decided to do another for Natasha to the same music. I don't know how much my story enlightened this decision, but it might have.

You've worked with a lot of choreographers; Robbins had a special reputation for being monstrous...

People who worked with him had these horror stories and at the same time fascination. But 99 percent of the time I had a great time. When he would come with his little dog Nick, I knew it would be a great rehearsal. When something troubled him, he would play with Nick and become Fun Jerry again. But when he got into that staring into the floor and very silent and very abrupt and very rude without understanding what he was saying, I left him alone. I just knew, Thank God I'm not the choreographer. Balanchine never had to remind company to pay attention; certain choreographers have to have a whip in their hand or a sharp tongue.

What is his legacy? What choreographers have taken from him?

His legacy is so abruptly divided between Broadway and ballet. I really think that inviting Robbins to be an associate choreographer Balanchine knew very well his Broadway work and the level of the talent, and especially Jerry's immense desire to work with him and admiration. Balanchine took him as an apprentice and trusted him. I think that was one of Balanchine's great qualities as a leader. But who took from Robbins? I don't know, I don't know, I really do not know. Jerry's a self-made

choreographer. He is an odd, odd bird in this sense.

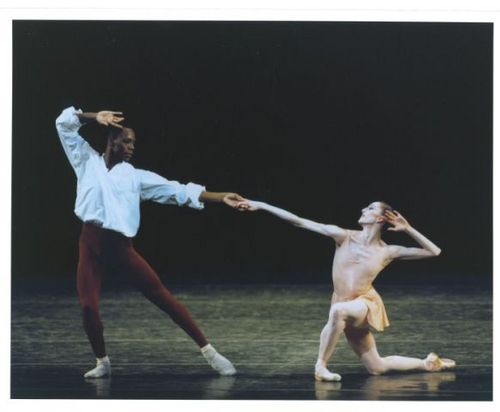

Albert Evans and Wendy Whelan in "Goldberg Variations." Photo, Paul Kolnik.

Albert Evans and Wendy Whelan in "Goldberg Variations." Photo, Paul Kolnik.

WENDY WHELAN, principal dancer, joined New York City Ballet as an apprentice in 1984 and was cast in Robbins and Tharp's "Brahms/Handel." She also originated a role in "Brandenberg," his final work.

As a young dancer, he was my Balanchine, I didn't have Balanchine, but I had Robbins. I feel very grateful and lucky for that. I was in the room with him every day for a good seven years, maybe a little more. Ten years almost.

What did you learn?

It was all about looking at each other, relating to each other, being natural.

I remember makeup and hair for his pieces he wanted to look more natural, more browns and earth tones. He wanted you to look real, like a human being.

And is that how it feels dancing it?

Yeah. Either a human being or a part of a social system. It wasn't like you're out of this world. You're either an insect or you're a person dying or you're a person studying or working--in a lot of his ballets you're wearing practice clothes--or you're relating in the spirit of each other, but it's never like you are Balanchine's Palais de Crystal jewel in the center. I never felt like that.

Did it feel more true?

For me, it was, first of all because I never knew Balanchine, so I never really knew my essence in his work. He wasn't there to accept me. With Robbins, I learned it was so important to him to be honest and true as yourself.

He finds people who have a strong individuality and who aren't afraid of exposing it. Because when you're in the studio with him, he wants you to open up to him. If you're shy, he's like, "I don't have time to waste. You either do it or you don't." He would push people to see their true colors and then he would go with that.

And you see that his best friends were really outspoken people, like Tanny LeClerq. She just said it like it was. And he appreciated it.

Tell me about the two pas de deux you've done in "Goldberg Variations."

First there's the crazy, Allegra Kent, acrobatic one [that Rachel Rutherford does now]. I adore that pas de deux. It goes to both extremes. It's a play on the bendy and sharp to the quick and sharp. And if he's going to put anything sexual in "Goldberg," it's in there. Yeah, throw a little sex into the second part.

And the third pas de deux [which Whelan did last season and will do again]?

I'm still figuring that one out. It's very epic, because it's so long. The tone is sad, and it ends very sadly. She goes over his back and reaches up, and she roolllllls down like a log from up high, facing the floor, and he lifts her off. It's unresolved. I think Jerry likes that, when there's not really an answer: a giant question mark in the middle. There's so many things in dance that you can't explain.

[About a duet in the Robbins-Tharp collaboration Brahms/Handel," a "West Side Story" for the classical set, with Robbins dancers in blue and Tharp dancers in green]

This might be my favorite section. It's very brief but it's kind of jiggy, which Jerry liked. His humor comes into his ballets a lot and it's a jiggy humor.

Was he a jiggy dancer?

Yeah, a little bit. There's a lot of stuff with hands on your hips just plieing to the music (dunk, da-dunk-dunk). It's just fun. That's part of the socialness of it. You're dancing with each other and there's some kind of deep-seated humor to it, and it just feels good to be dancing with your friend.

Kind of beautiful.

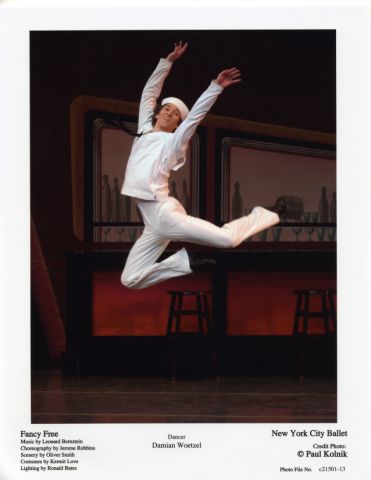

DAMIAN WOETZEL, beloved principal dancer with City Ballet, which he joined in 1985 and is leaving this season. This is the last chance to catch him in "Fancy Free" (above) or in "Dances at a Gathering," for example. His farewell performance is June 18.

"Fancy Free" was the first ballet I went to a rehearsal for. I was still in the school and Jerry had seen me dance and he told me to come watch him rehearse. I was 17 years old. The attention to detail within the choreography for each character is what stuck out. The corrections he gave weren't, You're doing the step wrong. It was how the step related to the character, and that was what was wrong. And he's famous for that in his Broadway life--through the dance came the drama-"Fancy Free" [Robbins' first ballet, from 1944] obviously previewed that.

When I got to do the ballet, I was doing the part he made on himself, and that gave me a little more insight into his thought patterns because they were in his body in a different way. He was so famous for his ability to demonstrate. The way he would do the [fans?] part in "The Concert," it was just beyond hysterical. He was so good at mime, for lack of a better word. As a dancer, to make that your own and imitate at the same time can be a life's work. But with Jerry's stuff, it's all so natural that it makes perfect sense. To use an example from "Fancy Free," the three sailors' every step is choreographed dramatically.

There's a tendency to overdo in an effort to succeed--in everything in life, probably--and Jerry's work succeeds by nuance and subtlety. I'm sure you've heard how he told dancers to mark in rehearsal and even on stage at moments, and that spoke to his desire to get beyond just energy. It demanded even more energy to do it that way, but it's a more sophisticated challenge.

Was there a difference between how he coached his situation ballets such as "Fancy Free" and his plotless dances like "Dances at a Gathering"?

There's a tremendous difference. He was adamant that there was no story in "Dances at a Gathering," for instance.

So what does he say about touching the ground at the beginning of "Dances at a Gathering"?

When we would do the touching of the floor, the mood was of temperature, of feeling the place itself. What did it mean? Ooh, he didn't talk about that. Definitely he would set the stage for the emotional setting. I think [that first section] was an archetype. It was a half-marked, half-danced remembrance of things past, and yet it's just a dance. And it ends with typical American nonchalance. It dwindles out, and that was very Jerry.

You know the story of Jerry seeing Eddie Villella in a shaft of light and that's where "Afternoon of a Faun" came out of? It's the unconscious conscious. The unstudied practice.

He has a sense of situation whether in "Faun" or "Fancy Free."

Yes, but those two are so wildly different in the way he gets into people's heads. "Faun" is a covert action, and "Fancy" is a might yawp. Those four bat-bat-bat-bat at the start of "Fancy"--can you imagine the arrival of Jerome Robbins [as one of the sailors in "Fancy Free" and as a choreographer]?

That is quite an arrival.

n

For more on the Robbins Festival this spring at New York City Ballet, I discuss Robbins' "Watermill" here and here his "Dybbuk" and here the problem with how the NYCB is dancing "The Goldberg Variations." Also: the Robbins influence on the extraordinary Bolshoi director-choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, particularly in this season's "Concerto DSCH" and the promising choreographer Benjamin Millepied, and a short notice of PBS's American Masters documentary on Robbins, airing February 18, 2009.

About a decade ago, the London-born choreographer Akram Khan and his Bangladeshi cousin were boarding a train from India to Bangladesh when police confiscated their passports and wouldn't return them until Khan's cousin slipped them some money. Then the cousins found a dead man in their carriage.

Khan moved to help the man's distraught wife, but his cousin told him to stay put. "They'll just blame you for the death," he said. "They need to blame someone, so they'll blame you." They'd recognize that Khan was a foreigner--he had insubordination in his eyes--and they'd throw him in prison and he'd never get out.

When Khan and the Moroccan-Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui sat down to plan a joint work in 2005, Cherkaoui asked Khan to tell him something he'd never told anyone before. Khan told this story. Now he and Cherkaoui tell it again at City Center this week.

Zero degrees--their harrowing dancing-talking duet--manages to be several things at once:

a confession; a meditation on confession (does it do any good?); and a powerful artifact of the crumbling end of these mendacious Bush years, when people are ravenous for public truth-telling and thoroughly disinclined to believe it.

Khan wants us to know about the police graft and the callous handling of the passenger's death, but he's also pointing the finger at himself for not stopping the bribe or helping with the passenger. To avoid a mise en abime of self-incrimination--guilt about even imagining it matters that one feels guilty--zero degrees does what most of us have been doing lately. It deploys the ironic confessional mode.

The train incident is recounted with all the idiosyncrasies of spontaneous speech--the stuttery sentences and the glorious ideograms that a dancer such as Khan, trained in the ancient, Indian storytelling form of kathak, paints in the air when he talks. But the men present the story together, in unison, like school boys. This confession is conspicuously staged.

What keeps zero degrees' irony from shading into the usual contemporary flippancy, though, is the way the dancing fleshes out the talking.

"The body doesn't lie," Martha Graham once said--and dancers have repeated it ever since. But everything lies. The only difference is that the body is a model confessor: it believes what it says as soon as it says it. Cherkaoui and Khan show us the virtue and vice in that faith.

The dancing begins with the men delicately interlacing their limbs. Gradually their movement becomes more rhythmic and violent, until Khan is bending Cherkaoui around like a Gumby doll and bouncing him like a ball. When it gets to be too much, they transfer their passions, their misery and anger, to their doubles--pale rubber sculptures that the acclaimed British sculptor Antony Gormley cast from their bodies. The dummies have been lying on the stage from the start.

It feels terribly sad, the men pummeling their weightless doubles, sitting on them, dragging them around. It's like a child hugging a doll when she has nothing else. The doll can only contain her feelings, it can't offer any of its own. These sculptures are to the dancers as zero degrees is to the incident on the train. The dance can testify to senseless death and political corruption, but it can't make them go away. It can't change the world.

Even more than the disturbing story itself, the helpless melancholy that arises from it is what makes zero degrees so timely and also so much wiser than its time.

Zero degrees runs this Friday and Sunday at City Center in New York.

Here's a very

short clip from the show. And here's another.

Photos above: 1. Akram Khan and Antony Gormley sculpture. 2. Khan and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Courtesy of New York City Center.

It's worth the trip, believe me. Founded and directed by former New York City Ballet star Edward Villella, the troupe's fluency--its capacity to energize the whole stage--is an essential quality of Balanchine, their mainstay, that sometimes gets tamped down. MCB will be performing three of his works at Tilles Center on Long Island.

It'll also be interesting to see what they do with Tharp's "In the Upper Room," which I, at least, have only seen American Ballet Theatre do.

Here's my Newsday profile on one of their loveliest ballerinas, Jennifer Kronenberg, plus Villella talking about the Long Island program. (Imagine a sidebar.)

April 20, 2008

"Arrive to go," the onetime New York City Ballet star Edward Villella likes to tell members of his swift and supple Miami City Ballet, which spins into Tilles Center next weekend. "Move!" he often exclaims during class and rehearsal.

Queens native Jennifer Kronenberg has never needed to be told. As a tot, the Miami City Ballet principal says, she "jumped around like a crazy girl" whenever ballet was on TV. Her grandmother suggested ballet class once a week. "No, no, no -- every day," responded Kronenberg. She soon got her wish.

Besides beauty, wit and an unforced musicality, Kronenberg has "a marvelously sympathetic quality onstage -- your heart just goes out to her," Villella says. And she's got range. "The wonder of Jennifer is she can do anything from 'Giselle' to Balanchine. Her ease of movement lends itself to so many areas, and that I don't see very often."

Kronenberg learned early that "part of being a good dancer is being a chameleon -- changing physically, theatrically and psychologically with each role," she says. She remembers Teresa Aubel, director of the performing arts academy Once Upon a Time in Richmond Hill, where she received the bulk of her early training, telling her, "You must do what the teacher wants. Everyone has something individual to teach."

Barbara Walzack -- with the New York City Ballet during its founding years -- instilled in Kronenberg the speed, placement of the body and musical sensitivity that she would need for Balanchine's School of American Ballet, where Villella discovered her. ("Miami City Ballet called," the school told her a few days after his visit. "They want to know your shoe size.") From the late Nicholas Orloff, once in various Ballets Russes, she learned "to feel free," she says. His classes always ended with flying leaps.

And since 1994, when she joined the Miami troupe as an apprentice, she has proved equally receptive to the individual lessons of its large repertory. She's been wittily urbane in Balanchine's "Rubies" (what she calls her "super exciting, super nerve-racking" first big role); mesmerizing and mysterious in his "La Somnambula"; and in his "Ballet Imperial," a woman so lovely in her majesty that her lover will probably never recover from her saying goodbye.

At Tilles, she confronts a whole other beast: "In the Upper Room" by Twyla Tharp, of "Movin' Out" fame. It completes a program of Balanchine works that includes "Raymonda Variations," "Sonatine" and "Tarantella."

"It's calisthenic exercises--karate, boxing, jogging, all kinds of things from the gym-- turned into pure jazz," Villella says. "The 'upper room' is where the mind goes when the body is fully physical."

One of only two dancers onstage at start and finish, Kronenberg embodies "the epitome of physical well-being," she says. "This dancer is strong and confident and getting her kicks out of driving harder and harder." Perhaps like Tharp herself. After working with the choreographer on the world premiere last month of "Night Spot," to an original Elvis Costello score, Kronenberg can attest that "she's intense. At the end of every rehearsal, she would say, 'Excellent. Tomorrow, do more.' She brought things out of dancers I'd never seen before."

As for the 40-minute "In the Upper Room," from 1986, "It was such a triumph the first time we made it through," says Kronenberg. It took weeks to build up to that point. "I never imagined I could feel that exhausted."

Villella has four of a kind

Edward Villella talks about the works that Miami City Ballet will perform at Tilles Center:

"Raymonda Variations." Balanchine embellished the 19th-century grand Russian manner, which he understood perfectly, with 20th-century speed and sophistication. He was responding less to the "Raymonda" story [about a vivacious young woman in need of a husband] than to its flavor.

"Sonatine." It's like a very fine piece of Limoges china. It's about the gentle regard between man and woman in French Romanticism. It's an homage to Woman, which of course was the Balanchine credo.

"Tarantella," made on Villella in 1964. When I joined the New York City Ballet and got to do "Prodigal Son," a critic asked, "Why are you giving a kid like that a role like this?" Balanchine said [Russian accent], "Because, you know, he looks like nice, little Jewish boy." I expect for "Tarantella" he thought "nice little Italian boy"!

"In the Upper Room." A good piece to end with, as there's not much you can do after it except beg for a cold beer!

WHEN&WHERE Miami City Ballet performs Friday and Saturday at Tilles Center on the C.W. Post Campus of Long Island University, Route 25A, Brookville. On Friday, Edward Villella will give a pre-performance talk at 7 p.m. $5 with tickets. Tickets $40 to $75. Call 516-299-3100 or visit tillescenter.org.

Copyright © 2008, Newsday Inc.

Forsythe's style looks different here than on his own company--not so in your face but also implacable, whiplash yet static--and maybe that's why I liked it so much.

The Kirov dancers are exceptional at switching styles, probably because they've been trained so solidly in a single school that they know what a style is. Still, they bring to Forsythe a softness and slipperiness--as if we've entered a world where the sound has been turned off--that probably returns the work too solidly to ballet for his own taste. It expresses a tenderness and curiosity toward this old idiom that I haven't seen much from him (and certainly not from all the Forsythe spin-offs). Maybe the difference is that these are earlier works, from 1985 to 1996, while the stuff that he's brought to BAM in the last several years has been more up-to-date. In any case, I was thoroughly engaged--delivered to the dances' world. It helps that we get a whole night devoted to Forsythe and that, unlike the classical ballets, these fit on the City Center stage.

Dancers I especially couldn't take my eyes off:

--Diana Vishneva in "Steptext," one woman among three men making a real-- uncontrived--story out of her outlandish figures.

--Olesia Novikova (black hair, very white, open face) bringing out the Balanchinean rhythm in Forsythe's homage to the master, "The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude." Novikova moves like a pebbled stream, with small but startling bumps in a constant flow. I think this is what people mean by Russian cantilena: however much rhythmic counterpoint the steps involve, you feel the rush of the whole passage rather than just the push and pull of discrete moments. It's like being inside a dream.

--Henna-haired Ektarina Kondaurova had that power too in the central inside-out adagio of "In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated."

Anyway, the Forsythe program only continues through tomorrow (Thursday). Then the company is on to Balanchine for its final three days at City Center, which should also not be missed.

UPDATE (4:30 pm, Wednesday): A friend writes,

Thank you. This is great. Can you explain why he kept the house lights up so long, with the doors open at the beginning? I found it so distracting (I was sitting in the back).No, I don't know, but, yes! it was distracting--I think the lights and the doors were probably deliberate, but I wonder about all the usher and late-patron talk.

You remind me of something major I forgot to mention: Forsythe's propensity to cut up the stage space and sink the suspension of disbelief. He likes to pull down the shades, as it were, either by lowering the pitch black scrim at the front lip of the stage or by having the dancers fall out of performance mode. (They walk into the wings like they're headed to the drinking fountain on the margins of a rehearsal room, or they stand in a loose first position, pressing their toes into the floor, before they begin the dancing, which, by contrast, never looks improvised.)

I think the point is less to break down the fourth wall, Brecht-style, though it has that effect too, than to do the live-performance equivalent of a handheld camera or a jump cut, which reminds you that someone is choosing these angles, this cut. Forsythe is showing that the edge of the performance isn't the edge of the stage but sometimes more and sometimes less: a permeable, malleable boundary. And that's how he thinks of ballet, too: the code isn't fixed but breakable and remakeable. Sometimes his stage maneuvers really work theatrically--as in the ending of "Approximate Sonata," when the scrim lowered, so only Elena Sheshina's calves were visible, before the lights blacked out, and you could imagine her dancing all night--working out the approximations of this sonata. And sometimes the maneuvers feel gimmicky. That's when I'm thinking, "But I've seen this already."

Many thanks for the question.

Eva writes: From what I've read, I believe the funny business with the houselights and the open doors (allowing ambient noise to enter the hallowed hall) are a deliberate part of the scheme. I found that--and more--to be a bit too contrived for my taste. And besides, if you trouble to warn people that they are going to be facing some unorthodox theatrical approaches, and they read that and settle back, thinking, "Okay, so this will be weird," don't you kind of undercut the effectiveness of the weirdness? Very, very few people seated near me appeared to be distracted or disturbed in any way by the lights and the intruding conversation. The strategy seems pointless to me and nearly childish and definitely tedious after a very short while. That said, the whole evening became, for me, an opportunity to savor the coltish dancing of Vishneva, who is a marvel.

Apollinaire responds: Eva, I love your irritation--it makes me want to cheer, especially after I gave such a sober (very likely pretentious!) explanation. And I definitely know what you mean about "nearly childish." Forsythe can be so charmlessly impudent. "Kammer/Kammer," at BAM a few years ago, started with one of his dancers heckling the audience, telling us all off for being bougie hipsters. It was like an EST session, where you pay to be abused; I was very tempted to heckle him back. Anyway, maybe because this was mild by comparison or because there was more to it than postmodern self-reflexive cleverness or because the Kirov dancers softened the attitudinizing and also were clearly happy to be dancing this stuff (especially Vishneva!), I felt willing to believe he was up to something beyond a taunt. I definitely know what you mean, though!

I'm so glad you liked Vishneva! Yeah, a marvel.

...in case you have yet to catch this phenomenal odissi ensemble on their U.S. tour, their performance at the Wang Theater of the Stony Brook University campus in Long Island on Sunday is your last chance.

BY APOLLINAIRE SCHERR

Special to Newsday

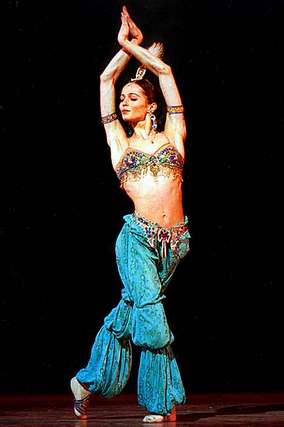

"Odissi is based on the s curve - the infinity curve," says artistic director Surupa Sen about the Indian classical dance form that Nrityagram Dance Ensemble brings to Stony Brook University next Sunday. "We never really finish a circle and we never make a straight line. Even our eyes won't look directly. There's always a little bit of an arc, which gives the movement a sensuality and a sculpturalness."

As it should. Hundreds of years old, Odissi grew out of the voluptuous poses of temple sculptures in northeastern India. "Odissi carries images of another lifetime," Sen says. "In a sense, our dance belongs to another world."

In another sense, though, it belongs very much to this one. In the past decade, the company of five women from a dance commune outside Bangalore has achieved renown across India, in Europe and the United States because it has succeeded where many contemporary groups have fallen flat. It has extended an ancient tradition without stretching it thin.

The contours of a Nrityagram show are conventional enough, beginning with an invocation to a Hindu deity and ending with a prayer. And the stories the dancers tell derive from ancient texts, as do the myriad evocative gestures with which they tell them. But Sen, the troupe's choreographer, also takes selective advantage of the Western dance arsenal: the jump and reach, and the poetic possibility of group set against solo.

It's common in Odissi to turn--with the upper body moving in mesmerizing figure eights a beat behind the hips--and to gallop. But because Odissi dancers often continue past middle age, the turns tend to be demure and the jumps low to the ground. Not here. Thanks to the latest body-conditioning techniques, Nrityagram dancers bound into the air with ferocious spirit and their chain of turns conjures a storm. When the steps grow calm again-- the body settling into that suggestive s -- the contrast is palpable.

Odissi is traditionally a solo form, with one person playing all the characters and traveling back and forth in time. Sen, however, has two dancers trading off in the roles, to profound effect. Take, for example, a dance in which a young woman catches sight of Krishna pining away for the goddess Radha and runs to tell Radha. "Our religion has always been celebration--mostly of love," Sen explains. But the additional dancer makes the relationship between the lovers no more important than that between the two women or between the storyteller and the listener, including us. Sen sweeps us in especially close.

Sen's innovations have caused some traditionalists to accuse her of transgressing classical dance's frame. "But I don't know what they mean," she says. She likens Indian classical dance to Sanskrit, which "is already like poetry, because it contains the roots of so many other languages." The root language that India's 2,000-year-old dance-theater bible, the Natya Shastra, lays out is meant to blossom into new images, she argues.

Life at Nrityagram -- the rural dance village established 18 years ago by ensemble founder Protima Gauri, who died in 1998 -- lends itself to this methodical approach. Brilliant senior dancer Bijayini Satpathy has "just discovered Google," she exclaims, for searching out Sanskrit stories for the dances, but otherwise the dancers' routine is decidedly low-tech.

Dance class, rehearsal, household chores, yoga and tending their individual garden plots: the workday starts at 5:30 a.m. and ends at 10 p.m. On weekends, the dancers sleep in, wash piles of sweaty practice clothes and teach the local children. Once upon a time, soloist Pavithra Reddy rode her bike to Nrityagram from the family farm nearby for these free classes.

There is little to keep them from their devotion -- no male dancers, for example, "carrying lots of chips on their shoulders because they don't want to be bossed around by a woman," says Sen.

Still, a person has to learn to make this humble lifestyle work for her. It took Sen years. "I've grown up mostly in cities," she says. "I didn't know one leaf from another when I first came to Nrityagram. This relationship that Protima wanted us to have with the land, I understood only after she died. It's the development of something from the seed."

WHEN&WHERE Nrityagram Dance Ensemble performs "Pratima: Reflection" Sunday April 13 at 6 p.m. at the Wang Theater at Stony Brook University. Tickets $10-$15; $25 for first three rows. Call 631-632-4400 or e-mail wangcenter@stonybrook.edu. (A workshop will be held Monday 1:30-3:30 p.m., free for ticket holders; $10 others.)

Copyright © 2008, Newsday Inc.

Photo by Stephanie Motta. Pictured first and second in this curvaceous line up are soloists Pavithra Reddy and Bijayini Satpathy.

I'm under the gun, so won't be able to report on the Kirov's fantastic Fokine program. But my friend Andy Podell, a playwright who loves the ballet, went this afternoon, and sent me this wonderful response when I asked via email how it was. I've put my interjections in brackets and italics. I saw a somewhat different cast earlier in the week. Here's Andy:

It was great. Very strange audience reaction. No applause for Gergiev. Tepid applause until Lopatkina's Dying Swan and then lots of adoration for Igor Kolb. [I think it was actually Igor Zelensky--according to my updated press release.]

I liked both Nadezhda Gonchar and her partner Yevgeny Ivanchenko in the Chopiniana pas de deux. I liked Gonchar's long expressive face and the effortless and gravity-defying way Ivanchenko lifted her.

They really worked well together--zero sexual chemistry, but that's not exactly what you need for Chopiniana. They were the highlight of the evening for me.Yulia Bolshakova was also fun to watch, but had kind of a clunky descent from her leaps. The corps was great but there were a couple of boo-boos, with one really big one towards the end.

One of the corps tripped and fell during one of the long stage crossings, and other members kind of scooped her up and carried her back into the movement. Then the curtain fell and rose, and for the second curtain call half the cast was revealed exiting from the stage and the drop curtain for the ballet had already been pulled up revealing scenery from Scheherazade shoved up against the wall.

Spectre of the Rose was a disappointment. No connection between Leonid Sarafanov and Gonchar. Sarafanov was beautiful to watch, but I can't believe that the ballet was that ugly to look at. Really stupid choice of day-glo rose for Sarafanov's outfit. The whole thing looked tacky and embalmed. Yuck.

Lopatkina's Dying Swan was over too quickly for me. It's an odd piece and would probably do better wedged in between a number of short pieces. It was given too much weight as the closer for a short second act. The program bill informed us that Lopatkina was the finest contemporary interpreter of the role, so we all had to applaud loudly.

But I did feel that there were some really shocking and radical things in the piece and Lopatkina's interpretation was excellent. I loved how it begins as a kind of romantic riff on Swan Lake, but then suddenly there's these really jagged and unsettling movements. The sharpness of the swan's death throes are a nice contrast to the music and the Petipa-influenced template. It's kind of a great piece--modernism emerging out of classical ballet. [wow, you're right!] Lopatkina used her bony bony body to great effect. The whole thing was too dimly lit for me to see what she was doing with her face. Too bad. I would have liked to have seen Vishneva perform it. Did you see her? [Not yet: Saturday matinee. I agree about Lopatkina: able to convey the dying very affectingly in a few, modernist strokes.]

Scheherazade was also a surprise for me. I'd never seen it and at first I thought it should be shut up with Spectre of the Rose in an archive. But then it started to really dazzle me. It's worth seeing just for Fokine's ensemble choreography. And the ensemble builds and builds. It's orgasmic. Speaking of orgasmic, Vishneva and Zelensky sizzled. They were both spectacular. He is big and hulking and studly, or at least he seems that way from the audience. But Vishneva created the sexual tension. She's remarkable. After seeing her in (was it Giselle?) I can't believe it's the same dancer. The entire center of her performance was her sinuous waist. She was bold and unapologetically erotic. The best moment of the ballet was when Zobeide bribes the Eunuch and opens the final door that will let out the Golden Slave. Zelensky's leaping entrance got the requisite applause, but Vishneva's dramatic pose while she waits for him was what made the entrance. I kept thinking the same thing throughout: she's partnering him, not the other way round.

Also thought about the two entrances of what were Nijinsky ballets. Both leaping entrances... both ejaculatory. But Spectre of the Rose failed to come to life at least in this production, while Scheherazade came through loud and clear and is still breathtakingly erotic.

A lot of fun!

Andy

Apollinaire responds: I saw Vishneva with Kolb, and she held the show together then too, even when she was reclining over near the wings, her lips parted like Marilyn Monroe. My favorite moment was when Zobeide kills herself. The turbaned master hands her the knife, not as a dare but to assure her he won't kill her, as he's just done to her lover, the Golden Slave. And she's sort of dazed by this opportunity--constant erotic heat will do that to you even if you don't have to decide whether to live or die. But then she points the knife at herself, pauses because it has made the decision for her and she's still catching up with it, then plunges it in. A much different suicide than for Juliet.

The Fokine program repeats Friday through Sunday but with Harald Lander's Etudes replacing Scheherazade. At City Center.

Photo of Diana Vishneva in Scheherazade (somewhat different costume, I think).

...in the Kirov's three-week season at City Center. As top shade in "La Bayadere" last night (led by doll-like Alina Somova), she moved with the wind at her back, like a prisoner of Dante's Inferno, the weight of memory and hope flying away from her. Until she appeared, most everything had been so studied.

Tonight, she leads in a tidbit from "Raymonda" (what's with these tidbits? Would have much preferred one long ballet). Later in the season, she dances Nikiya in the "Bayadere" 3rd Act, the lead in "Rubies" and a pas de deux from "Diana and Acteon," and some Forsythe.

This is the first I've seen of Novikova, so I don't really know how she'll do in other parts, but am excited to find out.

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments