foot in mouth: November 2007 Archives

The European philosopher-choreographer-king Maurice Bejart died on Thanksgiving (in case you live in a cave), and a week later the Alvin Ailey troupe premiered his "Firebird" at their gala. Which meant even at Newsday, where reviews have come to be frowned upon, a piece was in order.

What a hapless task! What was I going to do if I didn't like the dance--which seemed more than likely, given how I'd felt about pretty much every other Bejart ballet I'd seen? I believe in honoring the dead, and whatever you might think of Bejart's choreography he's always seemed as sweet and kind a man as an artist could be.

Well, I needn't have worried. "Firebird" is a lovely thing--dated in the nicest way, with such innocent and liberating homoeroticism. The Ailey dancers have done better by the choreographer than his own dancers ever did. I make a case for why.

The magnificent Clifton Brown as the Firebird. Photo by Paul Kolnik. (The other standout in the cast--and all night: Linda Celeste Sims, far right.)

The opening chords of Tchaikovsky's "Serenade in C" are a beginning and end in one. Like a prince descending the marble steps of the palace to be crowned king, the progression of chords moves with stately dignity--but not just downward. For every couple of steps down, there's one up, and even an abrupt pause to take in the full measure of the occasion. Tchaikovsky does not begin in medias res but at a chapter's end.

Balanchine's response is to make a whole ballet about finality--how conclusions are always foregone, like the tide that rolls in to roll out again.

The curtain rises on several columns of women in moonlit-blue leotards and ankle-length tulle. The women's right arms are raised toward the eerie light.

At New York City Ballet (pictured above) and San Francisco Ballet, the dancers turn their heads straight to the side and look so unflinchingly over their flexed hands at the night sun that you understand why they would soon turn away, framing a cheek with the back of a protective palm as if they'd just been slapped: a person cannot stare into the face of fate for long without it burning.

A couple of weeks ago in their first visit to New York in more than two decades, the Pennsylvania Ballet personalized that sublime power. The women gave their chins a coquettish tilt that belied the sober recognition and resistance of extended arm and flexed wrist. The women resembled Giselle playing "I love you," "I love you not," with her delicate heart. The trouble they were headed for wasn't inevitable, it arose from their hunger for danger and joy. And when the Pennsylvania corps turned their gaze away, they seemed coquettish again, as if they were hoping this suitor (whose name just happened to be Fate) would come calling.

He does, of course.

But in the New York City and San Francisco Ballets, the women are not maidens in waiting, they are, as Foot contributor Paul Parish has suggested in an earlier post, "waves dashing against rocks, currents surging through pilings." They don't wait around any more than any natural element would.

A woman, however, emerges from them, from the foam.

She has feelings about the course things take, and she is left to die. Or rather, as in "The Rite of Spring"--another Russian story about a destiny so inexorable it's linked to nature--she is chosen to die.

When Death's henchmen carry her away, she becomes their queen, on a throne made of the four men's palms. She turns the throne into a ship, arching her back to become its figurehead. The wisdom of this paradox--you sail the seas only by drowning in them--is what makes the ballet so intractably sad.

By personalizing not only fate but also its immanent form--nature--the Pennsylvania Ballet isn't being stupid, it's just setting "Serenade" closer than usual to its Romantic antecedents.

So the ballet becomes especially poignant in its conclusion. When the woman (Julie Diana on opening night) reaches her arm along the floor to the departing man and his companion, you feel her terror. When, carried to her death, she arches so far back, her face disappears from view, you're struck by her sacrifice.

But Pennsylvania's "Serenade" hasn't prepared us for this stirring ending. In the churning sea passages, the Pennsylvania corps moves too small--and the problem isn't entirely the modest dimensions of the City Center stage. The women don't expand even in the rocking passages--a sauté forward, then one back, like a boat on a stormy sea.

So by the end, we don't feel the shock of recognition. We haven't stumbled on a no exit we always knew was there--realized that the story would have to have ended this way because this is what life is like: neither loving nor hating us, simply knowing with a logic as deep as the sea and as cold as an arctic sun what it will do with us. The puzzle is too large for us to grasp the whole of.

Balanchine seemed to acknowledge as much when he said of "Serenade" in his "Complete Stories of the Great Ballets" (edited by Francis Mason),

Because Tchaikovsky's score has different qualities suggestive of different emotions and human situations, the apparently "pure" dance takes on a kind of plot. But this plot contains many stories.

With "Serenade," Balanchine didn't just want to tell a story, he wanted to stand far enough back to show us the terms of every story. Perhaps that's why the ballet--the first he made in America-- holds such a special place in his work. It describes how ballets such as "Square Dance," "Divertimento from 'Le Baiser de la Fee,'" "Emeralds," and "Mozartiana" can be vivacious, swift, and virtuosic, yet offer truths so difficult to accept that if you had known ahead of time, you might have stayed home.

u s u s u s

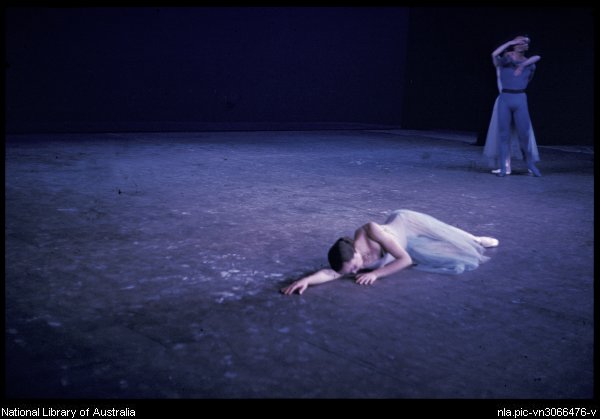

Photos: a.) A detail from the opening moment of the New York City Ballet production, by Paul Kolnik. b.) An archival photo of the Australian Ballet production by the late Walter Stringer.

Here's a short post on Pennsylvania Ballet's stupendous resident choreographer, Matthew Neenan, whose work was also presented for the company's City Center stay.

For more discussion of "Serenade" and particularly the role of the corps, go here and here with dance writer Brian Seibert, then regular Foot contributor Paul Parish dives in beautifully here, and I finish the discussion with this post. Enjoy!

Not to beat a dead horse--okay, to beat it--here's Jennifer Homans' review for the New Republic of the Nureyev bio that Foot in Mouth loves to hate. It's not that Homans agrees with ME-- that Nureyev was one of the greatest dancers--because she doesn't. It's that she both identifies the many problems with Julie Kavanagh's humongous and silly book, and proposes her own fascinating reading of Nureyev's life--why he might matter (something that escapes Kavanagh, even with a canvas of 700 pages).

Here are some enticing tidbits, in no particular order:

Nureyev was not always performing his sex life. Sometimes he was just dancing, and Kavanagh badly underestimates the capacity of art to be its own cause.

And

Nureyev's story was not at all the triumphant Cold War fable beloved of the media. On the contrary, it was testimony to the psychological and artistic scars inflicted by defection and exile--but also by freedom and fame. Defection set Nureyev free, but it destroyed his life and his dancing.

And

At unguarded moments Nureyev admitted that he was desperately lonely. He never fully mastered English, but neither did he spend much time with other Russian artists or emigres (he even shied from speaking his native tongue to Russian restaurant waiters, embarrassed by his provincial accent), preferring instead to forge ahead with a trail of adoring fans in tow. It was a linguistically and emotionally constricted life that contrasts painfully with the more open and personal relationships that he seems to have had in his Leningrad years. And if the Western press held Nureyev up as an exemplar of sexual and sartorial "liberation," they were in part missing the point: his profligacy was also tied to vengeance, fear, and what Ninette de Valois (a sturdy Irishwoman and founder of the Royal Ballet) called "the hysterical effect of freedom."

And

[I]t was not just that Nureyev made Fonteyn young again; they also stayed old together. As ballet in New York and London turned in more experimental directions, Fonteyn and Nureyev danced "the classics" over and again. Together they helped to make ballet a newly popular mass art, and they did it, paradoxically, by living in the past.

And, finally,

Kavanagh has done lots of research, although it should be said that much of it retraces [biographer Diane] Solway's well-laid path. (Kavanagh even reproduces one of Solway's chapter titles.) But she has done very little thinking. "Authorized" is no guarantee of insight, and Kavanagh's lengthy and effusive acknowledgments are far from reassuring: she has extensive debts, many of them to Nureyev's society-page devotees. ....[B]y focusing so hard on Nureyev's private life, Julie Kavanagh has not taken us any closer to the truth about why he mattered. Instead she reduces his art to the tedious and sordid details of his life. The people who "authorized" her book got what they asked for. The rest of us will wonder why we should care.

For the whole amazing article: here.

[Nureyev mania on Foot began with this commentary on the PBS documentary of his youthful days in Leningrad, moved on to outrage, as noted above, at the reviews of Julie Kavanagh's new mammoth biography that used the occasion to trash Nureyev, and relief at both this review and finally another that did more justice to the man than the bio itself.]

Well, actually, you can't.

It's one of the duties of the Ballet Master in Chief of big companies to create pieces d'occasion for the galas. (The French here is de rigueur, bien sur). Martins does his duty, but it seems to make him miserable.

His classical "trifles" have often looked straitjacketed, the contemporary work dogged, and the popular pieces a sop to the narcissism of the wealthy audience. (In his 2002 gala offering, "Thou Swell," which for some reason they're reviving this winter, a stage-wide overhead mirror was tilted toward us as if to say, "These elegant creatures onstage are you." So of course the dancers couldn't do much--they strutted around in their sumptuous coats, then took them off-- because that would have put the fantasy too far out of reach.)

"Grazioso," though, is glorious. Dedicated to the memory of New York City Ballet's beloved (and kinda crazy) cofounder Lincoln Kirstein, who would have been 100 this year, the piece is charming, breezy, engrossing.

The instrumental passages from Glinka's operas "Ruslan and Ludmilla" and "A Life for the Tsar" are more rhythmically nuanced than most music Martins chooses, and he responds to their plucky intricacy in full.

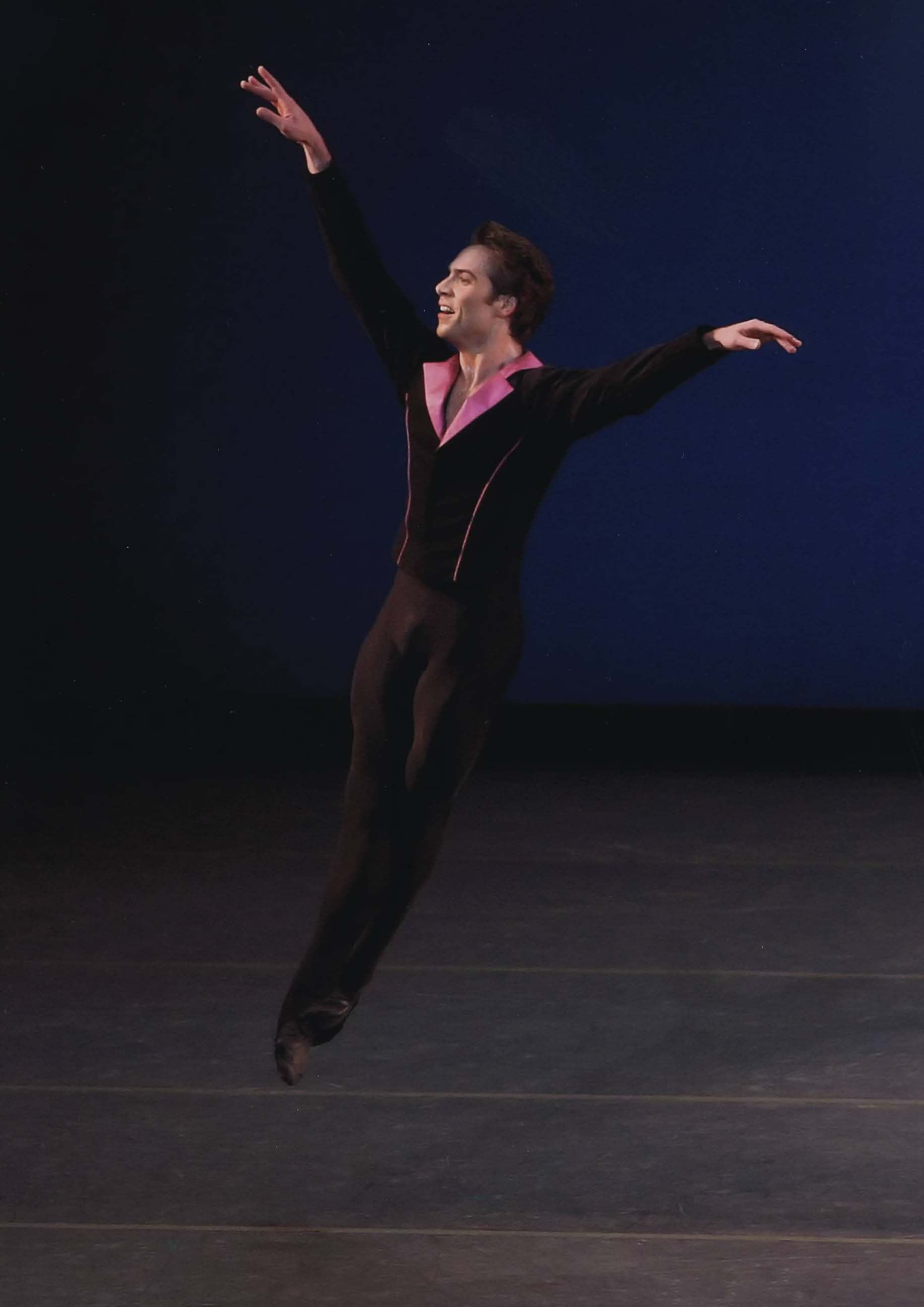

"Grazioso" abounds in the fluttery footwork one usually associates with women, or with fairy kings and their attendant sprites. It works beautifully on these men playing no one but themselves: Gonzalo Garcia (pictured), Andrew Veyette, and Daniel Ulbricht. (Photo credit: Paul Kolnik for the New York City Ballet.)

Martins also devises wonderful passages of partnering for Ashley Bouder. The always delightful ballerina may have three partners, but the effect is not cloying: the choreographer resists the contemporary habit of overpartnering this time. And though "Grazioso" looks back to the Rose Adagio from "The Sleeping Beauty," in which the debutante Aurora travels from suitor to suitor, there is little romantic subtext here. A good thing, as the association of ballet and romance is so rutted with cliché, it's become treacherous terrain.

Wending her way from one man to the next across the vast stage--how much space Martins gives her to luxuriate in!--Bouder promenades in different directions with each of them, with distinct interlacing of limbs for each pair. What lovely surprises, again and again.

"Grazioso" is not on New York City Ballet's winter schedule, so if it can't be substituted for "Thou Swell," maybe it will return in the spring? It would make a perfect spring dance.

NOTE: There are two other new posts today, here and here. Coming up, I hope (I really should learn not to make promises on a blog so dependent on reader response, and written in between things, because I'm always breaking them): a post on the Pennsylvania Ballet's Romantic with a capital R "Serenade" and on how great it is that they have Matthew Neenan as resident choreographer. Also, on the occasion of Performa 07, the second outing of the performance art biennial, a post on conceptual dance--how it works, or does it?

Happy Thanksgiving, even if that means spending the day watching bad movies and feeling pleased that you didn't have to leave the house. Don't let the family-industrial complex persuade you otherwise!

So remember how, starting back in May and continuing into June, then again in September (see the archives), we were lamenting that dance is not as popular as opera--and trying to figure out why and what to do about it?

In late September, reader Griffin suggested that dance do like the Met Opera and provide the movie theaters with high-definition simulcasts of sumptuous live shows.

And now they're doing it, they're doing it!!

The Canadians, of course.

A simulcast of the National Ballet of Canada's "Nutcracker" will run in 69 theaters from Vancouver to Montreal on December 22. Tickets: $10 for kids, $20 for adults. Lucky them.

Among the many wonderful responses to Monday's post about what choreographers might do to clarify their vision, dance critic Lori Ortiz of the Gay City News, the Performance Art Journal, Attitude, and other publications reminds us of the European practice of dramaturgy:

Hi everyone. I must pipe in to bring up one thing we are missing in our American dance, which is common in Europe: dramaturgy. Many here have never heard of a dramaturge, but I'm beginning to believe that dramaturgy gives European dance the polish and cohesiveness that distinguishes it. Case in point: "Oak Sacre" at Danspace Project (last week).

Apollinaire responds:

YES!! Though the word dramaturge may be offputting, the basic idea is great: an outside eye, and one specifically versed in drama.

I was urging a dramaturge or director for the big story ballets--an obvious place for extra dramatic consideration, if there ever was one-- almost a year ago. ABT's generally despised "The Sleeping Beauty," premiering this past May, employed just such a person and was much mocked for it, but some of my favorite touches--underdeveloped, sure, but there they were!--were the result of his guidance.

And did you see the Amsterdam-based troupe Emio Greco PC at the Joyce last year, Lori?

That company has two heads-- Greco and Pieter Scholten. Although Greco is trained in dance and Scholten in theater/directing, they've said it's hard to tell where one man's work begins and the other's ends.

That, of course, is the issue with a choreographer bringing in help: for it to do any good, the adviser has to be in deep sympathy with the choreographer and at the same time able to offer the distance that the artist himself doesn't have. Not easy to find such a match, but I'm not sure Americans are even looking.

Perhaps the structure of support makes it a more obvious model for Europeans: not only do they get more support (aka money), but companies tend to be allied with a theater, so the fact that dance is fundamentally a form of theater is always there before them.

In any case, Europeans seem much less attached to the idea of the Lone Artist beating against the tide (is that the shopworn metaphor I'm looking for?). Or maybe that's just the way it seems from here.

Thanks for writing, Lori.

Blogger Jolene of Saturday Matinee: Thoughts on Theater in the Bay Area has ignited a small storm of response with her relief that someone could clarify why a couple of ballets were duds: she thought the problem was her.

A whole lot of issues have come up, such as: What responsibility does a choreographer have to the audience? Do certain methods of composition lend themselves to obscurantism? Is choreography more guilty of muddiness than other arts? Is there something to be gained from an artist not worrying about how her work will be received?

The two reader responses were squirreled away in the comments corner, but now that I've received three--and three is company-- I've decided to make a post of them. You might want to read the original post first: here .

I hope more of you join in. I should note that the vast majority of reader responses on Foot are from people I don't know. (A couple of people I've come to know since.) So don't be shy--just civil.

From Christopher Pelham:

It's true that many dance artists have a method to their apparent madness that with some background we can decipher, that is, if we can can indeed get access to that background.

But then there are also a lot of choreographers, probably mostly younger and/or less experienced, whose steps only correspond to or are motivated by some arbitrary meaning or decision or idea that no audience will ever guess in a million years, an idea like, "I'll have my dancers raise their arms a lot because I saw someone do that recently and I kind of liked that..." or ... you get the idea.

I think a lot of dance by inexperienced or unestablished choreographers is wretched, but I do still wonder if maybe I'm just missing something.

But that just makes dance that is clear and purposeful and soulful all the more magical.

Apollinaire responds:

Hi, Christopher! Yeah, I agree that intentions and method can be really fuzzy, and that the choreographer has to meet us at least half way. In my experience, choreographers can get extremely self-righteous if they feel you didn't work hard enough to appreciate their genius, which makes me embarrassed for them. We don't owe it to any artist to like their work, though why would we show up if we didn't at least hope we would?

From Tonya Plank (aka Swan Lake Samba Girl):

Thank you thank you thank you, Christopher! I honestly feel that this is a huge problem with dance, that it is in large part why dance is failing. New choreographers don't seem to have any sense of audience. They seem to care only about themselves.

Christopher Wheeldon said he was primarily interested in his dancers' inner lives and experiences and who cares about audience. And then, shock, no one likes Morphoses' first program except people who already knew the dancers and had that to connect with.

All other artists -- novelists, playwrights, visual artists, filmmakers--at least try to make their point accessible on some level to the audience, at least give them clues as to what they are trying to say. From what I hear choreographers say, it is all about experimenting with their dancers, with movement. Then they get all upset because audiences aren't thrilled to sit there watching them experiment.

Ballet choreographer Jorma Elo said at Works & Process at the Guggenheim that he goes to his studio and works with his dancers and lets them grapple with movement, work the movement out. Most dancers are young and lack the artistry necessary to be the one in charge.

What is a choreographer? What do they see their job and their art as being about?

I find that I inherently trust a choreographer, such as Nacho Duato or William Forsythe, who has taken the time to write in his program notes what he is exploring, what he is trying to do in general terms, what he hopes to make an audience think about with his work. At least that shows me that they're outwardly oriented. That they're thinking of us and aren't simply self-absorbed.

Apollinaire responds: Thank you for writing, Tonya. Much food for thought.

I do think that dance, being both silent and inherently theatrical, has to offer us very clear guides to its unfolding--has to have a clear structure of intent. On the other hand, it's a tricky business for any artist to know if his intent is coming across.

Also, I would be wary of assuming that one method--such as experimenting with dancers--leads to obfuscation while another, such as a more dictatorial approach, does not. I think Forsythe, for example, develops the dances with his dancers. To get that to function well, you have to know how to direct them. Perhaps Wheeldon and Elo don't entirely know how to do that yet, but I wouldn't blame the method itself. In fact, for all we know, the source of the problem may have nothing to do with the method. We really can only judge what they've presented, as we don't entirely know their minds, no matter how much explaining they do.

Also, a lot of choreographers lay out their intent in program notes--and it clarifies nothing!! I guess this only goes to show that a choreographer not only has to know what she's doing but how to talk about it.

Finally, I think it's a real question how much an artist should think about the audience--and how she should think about us. To some extent, you don't want artists second-guessing themselves--trying to fashion their work after their expectations of its reception.

Anyway, it's all very befuddling, and I'm glad you've brought all this up.

From blogger Meg of Haul Your Paper Boats:

I don't think I agree that all other artists know that they need to respect their audience or readers.

Certainly there are writers who create their work with little or no thought to their readers for a variety of reasons: they believe they aren't writing for publication, they are trying to experiment with the conventions of storytelling, they are trying to use language in new and different ways, etc. And there are exceptionally difficult writers (particularly poets) who can leave their readers adrift in much the same way as choreographers leave their viewers adrift.

I think there are three major differences that make writers easier to discuss and understand. One is that it's a verbal medium, which makes it easier for us to discuss or write about. Another is that most of us have practice talking about things we have read. After all, it's something we were required to do in school. So we feel more prepared when we need to do so. The third is that more often then not, writers have editors going over their work. I'm very new to dance viewership, so I could be wrong, but it seems to me that choreographers have this sort of outside voice less often. Editors can serve as advocates for future readers by making sure that a work is cohesive, logical, and intelligible.

Moving away from writing to theatrical and visual arts, I think we can again find a lack of concern for the audience.

Certainly there are films or experimental plays that leave audiences befuddled or adrift. But again we have the presence of verbal as well as visual communication to help us.

Viewers of the visual arts are often just as confused as audiences of dance. And the artists generally provide just as little guidance. How many people say they just don't like or understand abstract art? Is the work of painters like Pollack, Rothko, or Twombly really any easier to understand than dance? Were these artists really more respectful of their viewers than many choreographers are of their audiences? I'm not so sure. And I think the same questions could also be applied to many 20th century musical compositions. Not so coincidentally, I think the fear of sounding like a fool is also present when talking about these art forms.

This is all a rather rambling way of saying that I don't think the problem under discussion here--communication with an audience--is actually exclusive to dance. Rather, it seems to me that there is often a divide between the artist and the people taking in the art. The divide may be larger and more problematic in some places than in others, but I don't think it's unique to dance.

That's just an elaboration of a problem as opposed to a suggested solution, though.

Apollinaire responds:

But what a great elaboration, Meg. Thanks so much for writing in.

Yes, every art has practitioners who either from incompetence or from a desire to push the form, don't look after their viewers/readers. The problem is: which is it? That's what I think we're grappling with here.

You help explain why Jolene might have hesitated to dismiss the seemingly experimental works of Elo and Millepied: she doesn't want to discourage the experimental impulse, as art depends on it to stay alive. On the other hand, she wants the real turtle soup, not the mock.

And I agree with you that it's harder to tell the one from the other in non-verbal, non-narrative forms: the comparison to visual art and non-vocal music, as opposed to novels or theater, is apt.

I also love your point that we learn how to interpret literature in school, but not how to think about music or visual art. However, I would argue that it's precisely the way literature is taught in school that makes it so hard for people to transition to non-narrative forms.

I spent several years teaching high school. The students mainly hated me, partially because I insisted that they stop treating literature as a puzzle to decode--the rose sym-BO-lizes love, the pearl, faith, blahblahblah. I wanted them to think about the effect the book had on them and how. Don't tell me what it means, I'd repeat, to their chagrin, tell me how. I wanted their learning to abet their natural wonder, not undermine it.

Anyway, the decoding method doesn't get you anywhere with dance. It really doesn't matter what the theme is, it matters how it develops. And nothing one learned in school will help with that.

Finally, yes!! Writers have editors, playwrights have the neverending workshop (which I wouldn't want to wish on anyone), filmmakers have cinematographers and editors and producers and so many auxiliary people, it's amazing that what comes out is ever coherent. And what do choreographers have? Their friends.

It's not that other choreographers can't help a person--a lot--but the difference is that one's peers have the same strengths and weakness of vision as the person who needs guidance, whereas an editor (ideally) really offers another perspective that doesn't compete. (That said, some of my favorite editors have been writers. They've just known how to switch hats.) Also, the choreographers don't have any obligation to take the feedback, which of course is a good thing: it would be terrible if they were dictated to. But it also allows them to mistake lazy habit for individual vision, etc.

I really don't know what the solution is, but I can't tell you how many dances I've seen that could have been brilliant with better editing; instead, they were just okay. It's so maddening, I've been tempted to offer my services in the offchance that we might all be spared that waste of spirit and talent and incredibly hard work.

UPDATE: More readers comment--and readers comment more!! Click here.

Ohad Naharin's "Three," performed by the Batsheva Dance Company at the BAM Opera House through Saturday, is what people like to call a "pure movement piece." It's an annoying expression in any case, as movement can never be wiped clean of history and metaphor (and why would you want it to be?), but it's especially off when applied to Naharin's gestural idiom.

Still, other pieces by Israel's preeminent choreographer, artistic director of Batsheva, have felt more issue-oriented. The barriers to Palestinian-Israeli peace dog every step in "Naharin's Virus," with its score by Arab-Israelis and a high black wall against which the dancers batter themselves and on top of which they shout useless invective. (BAM presented this dance in 2002.) And other pieces have been more dramatic. "Mamootot," presented by BAM at the Mark Morris studios a couple of years ago, bound us to the performers by a fragile umbilical cord of responsibility. The dance took place in the square, as it were, with the dancers repeating the sequences to each side. First you watched them without them seeing you and then you watched them come right at you. Enclosing them, our job was to absorb their ungainly beauty and their inwardness. At the end, they walked single file along the perimeter where we were seated and held a few of our hands too long while looking into our eyes. Would you return the gaze or look away? And how would you look at someone who brought you so close to the dance, to herself, maybe even to yourself?

With "Three," we are in our usual place--seated in an auditorium, where the performers can't see us. Our task is straightforward. As a talking head--literally-- on a video monitor during the first comic entre'acte puts it, we're to "Pay. Atten. Tion." For two sections out of three, you don't need to be told.

The movement is typical of Naharin lately. The limbs are crooked, the stomach isn't drawn up (as in ballet), the butt sticks out behind, and the hands gnarl into claws. The gestures veer toward the obscene, as if someone seemed to be scratching his balls when he was only picking lint off his trousers.

With gestures shooting out at earthy angles, the body is not a coordinated unit but made up of parts, each having its own say. What a lively, protuberant creature it is! (The 17 members of Naharin's Tel Aviv tribe are mesmerizing individuals without for the most part being showoffs.)

What's unusual for Naharin is the unison. It's as if he set up an experiment to test his language's limits: What happens if I confine movement so obviously individual to unison? And what happens to the unison when such freaky movement inhabits it?

The movement in the unison sections doesn't feel any less idiosyncratic, but it does seem more instinctive than willed. The dancers resemble a herd, a school of fish, a flock--animals moving from a collective and silent knowledge. And yet, the individual in the group doesn't seem to have to contain herself to move in sync with others. Unison becomes a lovely, miraculous feat here, one of those rare cases of having one's cake and eating it, too.

Glen Gould's rendition of Bach's Goldberg Variations proves a funny, apt choice for "Three's" first part, "Bellus" (or "Beautiful"). The eccentric pianist's emphasis on the knobbly moments in Bach's mathematical sublime brings out the uncouth angularity of Naharin's steps and even "Bellus's" structure, in which dancers walk on flatfootedly to dance together or alone.

Burbly, quiet Brian Eno works just as well for section two, "Humus" (Soil), for nine women. "Humus" is almost entirely in unison. Given the subdued character the mode possesses here, this section is the most quiet and serene, without ever being faceless or mystical or whatever association the hopeful fantasy of silent women carries.

The third section resorts to a musical collage of electronica, the Beach Boys, etc., plus tried-and-true Naharin choreographic formulas. For example, the dancers line up for some vogueing, each person presenting his "own thing."

Often with modern dance, I'm irritated that choreographers who have the opportunity to invent a whole movement palette (yippee!) make such pallid, shopworn choices. But Naharin takes avidly to his freedom. When the dancers are left to their own devices, though--or seem to be, anyway--they look less individual, not more. Unedited, "your own thing" turns out to be mainly someone else's: the unconscious both collective and spongelike, and a bit dull. Perhaps Naharin was exhausted by the time he got to part three. And no wonder: he has made a dance unlike any he's done before, and mesmerized us to boot.

Here is a 40-second video collage of the 70-minute "Three."

Photo credit: Richard Termine for the Brooklyn Academy of Music

Blogger Jolene of Saturday Matinee: Thoughts on Theater in the Bay Area writes in about my post last week on the Elo and Millepied ballets at American Ballet Theatre:

I completely agree with your interpretation of Elo's and Millepied's pieces. I just saw them this past Saturday at Berkeley and was a bit confused.

Do the choreographers really think that their pieces are going to be memorable or earthshaking? Did they push the boundaries of dance at all?

I felt that both choreographers didn't accomplish much with the pieces, although they weren't horrible either. They're just solid, "modern" ballet pieces. Filler, perhaps. Thanks for validating my point of view. I thought I was missing something.

Apollinaire responds: Thank you for writing, Jolene. I'm glad you liked the post. I'm also struck by the fact that you felt you needed your point of view validated.

I think one of the reasons people are afraid of dance--particularly contemporary work-- is they don't feel secure in their own reactions. Even the kinds of pointers you might get in a gallery--you know, that big binder with xeroxes of reviews from previous shows as well as an essay written for the occasion that puts the artist in historical perspective--aren't available.

And no one wants to play the rube--to come to some judgment that says more about his own ignorance than about the dance. So, you can't even enjoying being disgruntled. Which makes people not want to take a chance on something they might not like.

The website Dance Insider has just republished an interview from a few years ago with the boyfriends and girlfriends of a few professional dancers and choreographers. These guys are smart and have an inside track to what's happening onstage, and they still often feel that they've entered a conversation midstream.

The dance doesn't always give them a way in to its structure of meaning. And that's where dance, like music, makes most of its meaning--in its structure: how the piece transitions from section to section or step to step, how groups or individuals are used, how its language develops or not.

Part of the problem is us reviewers. I've been blabbering about this for a while, but here goes one more time! (From another angle, at least.) We tend to say what a dance means or what it does, but we don't always put the two together. We too rarely give readers some idea of how you go from steps to meaning, or even mood, in dance.

Of course, sometimes the dances don't mean anything to us. For example, until I'd seen the Ballet du Grand Theatre de Geneve, the noodling arms of Elo and Millepied seemed like nothing but stylistic affectations. Afterwards, I understood where they were coming from, even if I felt that the movement had been stripped of its sense--deracinated.

But when a writer does see the whole picture, she needs space to convey that understanding--to say how the dance is doing what it does or saying what it says as a way to arriving at what it is doing and saying. And ample column inches is something very few of us have.

Which is why blogging is nice. (If only it paid.)

Here is my Newsday review of the two world premieres at American Ballet Theatre this season, by Benjamin Millepied and Jorma Elo. I didn't like the ballets very much; neither did I hate them.

Writing in short form with little time doesn't lend itself to that mezzo-mezzo state of mind, a brain stewing after it's been stewed. I've noticed that my colleagues and I tend to list to one side or the other--say we liked a show more or less than we did. The challenge I set myself for this review was to stay right there in the middle: ambivalent. I got tangled up. It was all I could do to straighten myself out by deadline.

Sometimes with a review, there's a context for your reaction, which you don't have room to go into. In this case, it was the New York debut of the Ballet du Grande Theatre de Geneve at the Joyce, which I attended (with Tonya a.k.a .Swan Lake Samba Girl!) just after the ABT premieres. The dances--by Saburo Teshigawara, Andonis Foniadakis and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, choreographers based in Europe and not much seen here--made clear what was missing from Elo and Millepied.

As with many European companies with "ballet" lingering in their name, the Geneva Ballet isn't: the women aren't on pointe, there's no preponderance of partnering, and the vocabulary is not remotely balletic. Yet the pieces were true to their own odd selves.

The title of Teshigawara's dance, "Para-Dice," may be unnecessarily French--if it's a pun, could you please clue me in on the joke?--but the dance really does evoke a paradise.

When it started, with a line of women signaling with their arms, I thought, "Oh, no! Not more noodling arms!" (Elo and Millepied feature lots of noodling arms.) But the arms quickly became part of a whole: a quiet whole of imploding softness. One example: the women were dragged backwards very gently by the men at irregular intervals like a record you want to have skip because it repeats the most beautiful part.

Foniadakis' "Selon Desir" (According to Desire) could have been terrible. Dances about desire are often unctuous and self-proclaiming in a way that passion isn't. But this dance didn't layer on any such sheen.

It was rough and humble. All 15 dancers, men and women, were clad in silky, mid-thigh skirts and loose T-shirts--all different colors so the dancers resembled the multitude of voices in the St. Matthew Passion, the score. The dancers moved in big low steps and got thrown up in the air so forcefully, one person against another, that you could hear the smack of their bodies.

They kept rushing on stage. They danced even with their hair, thrashing their heads. But the dance wasn't mainly about being wild--you know, wild and groovy. Instead, like Mark Morris's "Gloria," it had a reverence for this oratorio of Jesus's ordeal and a desire to find a contemporary idiom for that passion.

"Selon Desir" goes on too long. Not just phrases but whole patterns begin to repeat, pulling you out of your overwhelmedness. With some cutting, though, the dance could be a masterpiece.

The Cherkaoui piece, "Loin" (Far), was why I'd gone. I'd seen pieces by the other two before and not been all that impressed. I was worried that, like so much European contemporary dance, the show would be portentous and empty, or cute and empty. Something and empty. But I'd heard about this wunderkind Cherkaoui and never seen anything by him.

The Cherkaoui was my least favorite. He threw in too many ideas, with the conceptual framework undercutting the dancing. The dancers intimated in their staged "confessions" that the dancing wasn't what mattered. What mattered was the cockroach-infested theaters they encountered on tour, or what mattered was their own incapacity to notice anything about the far-flung cultures they toured beyond those theater conditions. In any case, you began to feel foolish getting into the movement, and stopped. But at the very end, the dancing and the talking coalesced.

The rangiest dancer partnered two men at once. He twirled them from the end of his arms; they resembled protesters gone limp to avoid being charged with resisting arrest or men beaten unconscious or dead. In the end, he threw them on a pile made of all the other dancers and climbed on top.

"Loin" was a variation on the show's theme of a collapsing body. Each choreographer used that helpless torso in his own way, but never simply as a look. The choices they made were urgent.

That was how they were different from Elo and Millepied.

NOTE: If you are reading this on Sunday November 4 and you live in or around New York, treat yourself to Gillian Murphy as The Accused in Agnes de Mille's "Fall River Legend" this afternoon at City Center in ABT's last show of the fall season. Murphy gives an astounding dramatic performance in an amazing work of mid-century dance theatre. (It's about the repressed, of course, like Tudor's ballets, like Graham.)

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments