The opening chords of Tchaikovsky’s “Serenade in C” are a beginning and end in one. Like a prince descending the marble steps of the palace to be crowned king, the progression of chords moves with stately dignity–but not just downward. For every couple of steps down, there’s one up, and even an abrupt pause to take in the full measure of the occasion. Tchaikovsky does not begin in medias res but at a chapter’s end.

Balanchine’s response is to make a whole ballet about finality–how conclusions are always foregone, like the tide that rolls in to roll out again.

The curtain rises on several columns of women in moonlit-blue leotards and ankle-length tulle. The women’s right arms are raised toward the eerie light.

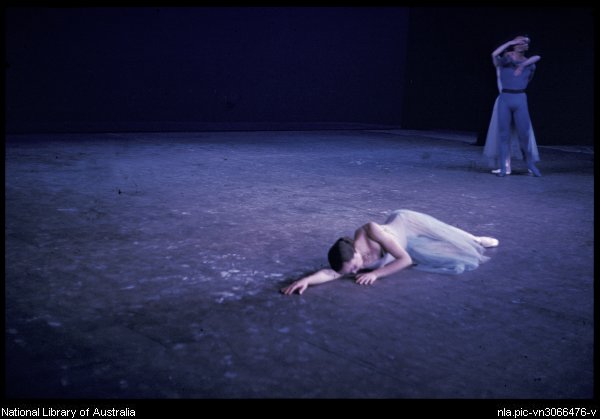

At New York City Ballet (pictured above) and San Francisco Ballet, the dancers turn their heads straight to the side and look so unflinchingly over their flexed hands at the night sun that you understand why they would soon turn away, framing a cheek with the back of a protective palm as if they’d just been slapped: a person cannot stare into the face of fate for long without it burning.

A couple of weeks ago in their first visit to New York in more than two decades, the Pennsylvania Ballet personalized that sublime power. The women gave their chins a coquettish tilt that belied the sober recognition and resistance of extended arm and flexed wrist. The women resembled Giselle playing “I love you,” “I love you not,” with her delicate heart. The trouble they were headed for wasn’t inevitable, it arose from their hunger for danger and joy. And when the Pennsylvania corps turned their gaze away, they seemed coquettish again, as if they were hoping this suitor (whose name just happened to be Fate) would come calling.

He does, of course.

But in the New York City and San Francisco Ballets, the women are not maidens in waiting, they are, as Foot contributor Paul Parish has suggested in an earlier post, “waves dashing against rocks, currents surging through pilings.” They don’t wait around any more than any natural element would.

A woman, however, emerges from them, from the foam.

She has feelings about the course things take, and she is left to die. Or rather, as in “The Rite of Spring”–another Russian story about a destiny so inexorable it’s linked to nature–she is chosen to die.

When Death’s henchmen carry her away, she becomes their queen, on a throne made of the four men’s palms. She turns the throne into a ship, arching her back to become its figurehead. The wisdom of this paradox–you sail the seas only by drowning in them–is what makes the ballet so intractably sad.

By personalizing not only fate but also its immanent form–nature–the Pennsylvania Ballet isn’t being stupid, it’s just setting “Serenade” closer than usual to its Romantic antecedents.

So the ballet becomes especially poignant in its conclusion. When the woman (Julie Diana on opening night) reaches her arm along the floor to the departing man and his companion, you feel her terror. When, carried to her death, she arches so far back, her face disappears from view, you’re struck by her sacrifice.

But Pennsylvania’s “Serenade” hasn’t prepared us for this stirring ending. In the churning sea passages, the Pennsylvania corps moves too small–and the problem isn’t entirely the modest dimensions of the City Center stage. The women don’t expand even in the rocking passages–a sauté forward, then one back, like a boat on a stormy sea.

So by the end, we don’t feel the shock of recognition. We haven’t stumbled on a no exit we always knew was there–realized that the story would have to have ended this way because this is what life is like: neither loving nor hating us, simply knowing with a logic as deep as the sea and as cold as an arctic sun what it will do with us. The puzzle is too large for us to grasp the whole of.

Balanchine seemed to acknowledge as much when he said of “Serenade” in his “Complete Stories of the Great Ballets” (edited by Francis Mason),

Because Tchaikovsky’s score has different qualities suggestive of different emotions and human situations, the apparently “pure” dance takes on a kind of plot. But this plot contains many stories.

With “Serenade,” Balanchine didn’t just want to tell a story, he wanted to stand far enough back to show us the terms of every story. Perhaps that’s why the ballet–the first he made in America– holds such a special place in his work. It describes how ballets such as “Square Dance,” “Divertimento from ‘Le Baiser de la Fee,'” “Emeralds,” and “Mozartiana” can be vivacious, swift, and virtuosic, yet offer truths so difficult to accept that if you had known ahead of time, you might have stayed home.

u s u s u s

Photos: a.) A detail from the opening moment of the New York City Ballet production, by Paul Kolnik. b.) An archival photo of the Australian Ballet production by the late Walter Stringer.

Here’s a short post on Pennsylvania Ballet’s stupendous resident choreographer, Matthew Neenan, whose work was also presented for the company’s City Center stay.

For more discussion of “Serenade” and particularly the role of the corps, go here and here with dance writer Brian Seibert, then regular Foot contributor Paul Parish dives in beautifully here, and I finish the discussion with this post. Enjoy!