Douglas McLennan: December 2006 Archives

John: I wasn't at all suggesting there wasn't a place for the classics (when I was young I never appreciated all those disparaging remarks about "old chestnuts" as people used to call them. To me hearing them the first time, there was nothing old or tree-fruity about them). And I remember clearing the moment I decided I wanted to become a pianist - it was after a radio broadcast of Grieg's Piano Concerto. I sent out the very next day to order the score.

I was just suggesting that lack of artistic imagination is almost always the result when you set a low bar. And that while it might seem like going after non-arts fans might seem to be the richest vein to try to mine (it's such a big group), they're much harder to convert into supporters of your work. I fear that newspapers spend so much time trying to chase after people who don't want them that they neglect those they already have and that do care about them.

You say that most intelligent people you know read the daily paper. Unfortunately that's no longer the case in many cities. It's certainly not true here any more in Seattle. When I first started working at the Post-Intelligencer in 1988, everyone I knew read at least one of the two daily papers. By the time I left in 1999, that was no longer the case. The paper of choice here is the New York Times. Intelligent people disparage the local dailies. Not because of the traditional breaking news coverage - which both do a decent job of - but I think it's because there's too much dumb stuff in the mix. People like to feel like they're smart (no matter how smart or dumb they are) and I think that for smart people, the dumbed-down dailies are an affront.

I so often hear people complain there's nothing in the dailies here. That's not really true. If you want to find out what the big issues are, the dailies are still the only place you can keep up. And there's great reporting in both papers, almost every day. But the general level of dumbness makes people dismiss the entire package. The message isn't "this is for people who care and want to be informed." The message is "we're trying desperately to figure out what (particularly young) readers want and how we can lure them in."

You're right that a lot of arts coverage has moved to the web. The opinions there, are, for the most part, filled with more personality. There's starting to be some good reporting and commentary on the web, and I think that is definitely the future, given that traditional print seems to be abandoning arts journalism. Two excellent long-time established newspaper critics told me separately this year that they accepted buyouts at their newspapers because they felt the papers had left them. That is, the papers were no longer interested in what they were doing, and so they left to pursue more fertile ground.

I know that while you say you're retiring, that people like you don't really retire - they just move on to the next phase, and I'll be interested to see what that next phase is. I'd like to thank you for coming on the blog this week and talking about the book, the arts and arts journalism. And I'd also like to thank you for the years of pleasure you've given many of us as a cogent writer about culture. I hate sounding like a fan, but there you have it.

Doug:

I retain a certain affection for dumbed-down classics, since (even with childhood piano lessons) I was led into my love for classical music as a young teenager by Arthur Fiedler. Still, I agree with your notion that high-arts organizations should concentrate on serious arts for those who love them. But that does not mean sticking doggedly to the classics, even when well performed. Aesthetic conservatives are too willing to attack anything that deviates from the norm as dumbing down. Innovation -- in repertory, in performance styles, in concert and radio formats -- can be terrific. Or dumb. You just have to make the distinction for yourself.

There is also a difference between overpraising the local product in a boosterish, non-credible way and being supportive of an arts community to which you have devoted your life. Martin Bernheimer reacted viscerally against boosterism, feeling that only if fledging efforts were judged against the most rigorous standards could the strong survive. But I think of Deborah Jowitt, the longtime dance critic of the Village Voice. She tries to be supportive, and some people complain that in saying positive things about most everything (but not everything), she undercuts her crediblity. Yet if you read her regularly, you can peek between the lines. And her love for and knowledge of dance is so palpable, and her prose so elegant, that she fills an invaluable role.

Nice of you turn our conversation back to me, me, me. It's funny, your comment about "zingers". Phillip Lopate, in his review of "Outsider" this coming Sunday in the NYT Book Review, also notes my penchant for what he sees as overcute endings, even though his review is mostly smart and favorable (not necessarily the same thing). But that's just practicing journalism, in which the model of the lively lead and the ending that pops (the"kicker") is drilled into us from the outset of our careers. I do think a good kicker can sum up a review or turn the reader in a last-sevcond new direction in a nice way.

My main mentor as a critic was Dale Harris, the longtime ballet and opera critic (and college literature professor and art critic and foodie and on and on). Our lives ran parallel for a long time, until his death. He was a graduate student when I was an undergraduate at Harvard, and I took over his opera program on the college radio station when he needed to devote himself to his Ph.D. orals. He was teaching at Stanford when I was a graduate student at Berkeley, and we both wound up in New York. When I was preparing to take over his Harvard opera show, he demanded written practice scirpts which he scrupulously edited. I can't say my style or even all my values were Dale's. But his influence loomed large. So did Virgil Thomson's, even though we were very different people and he never worked direclyy with me as a mentor. Like most everyone, I loved his insights and his prose style. And when we collaborated on "The Virgil Thomson Reader," I found him pretty special, too, for all his waspishness toward others.

One last comment, circling back to the ideas of niche audiences and how the Internet can satisfy them better than dumbed-down general newspapers, and of specialist vs. generalist critics and the sense of lost community I feel in the arts and arts journalism today. I spent my life working in dominant instituttions: Andover, Harvard and Berkeley, the Oakland Tribune (big in Oakland even if the SF Chronicle dominated the Bay Area), the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times and Lincoln Center. I admired arts that could reach out and bind people into a community. People who didn't like popular music, or didn't like journalism, could complain that they reached the masses because they were dumbed down, or just dumb. But I clung the the notion of universal, shared values, for all the individual artsworks that appealed intensely to the few.

I love all kinds of art, from the most esoteric to the most accessible. But I cherish the ideal of an art that speaks to our deepest, most basic values. And I cherish the idea of a means of communication -- a newspaper -- that is still read by most literate people in a commuinity and can provide a basis for lively discussion, face to face or on the Internet. People complain about the undue power of the Times, and certainly London, which like New York a century ago supports several good competing papers, provides print journalism eqivalent to the Internet today, with a diversity of competing voices. We need both, the jangling dissonance and the harmony that can bring them all together. The Internet is a marvelous tool, one we have only begun to explore. Maybe something one day will arise online to provide a communal equivalent to the role of leading newspapers today. Mankind needs a sense of togetherness, and if print journalism goes the way of the dinosaur, which it well might, I hope something of similar magnitude and authority will rise in its place. Not the authority that is "right" where others are "wrong," or that silences contrary opinion. But something that we can all share. I've been a part of that over the years, and I'd grateful.

I'm grateful to you too, Doug. In Germany, at the end of any major interview in a newspaper or a magazine, the journalist says, ritualistically, "Thank you for your conversation." So I thank you. Thanks for inviting me to participate in this weeklong back-and-forth, even with downed trees and lost power and your hectic trip to Minneapolis and crashed computers and and the holiday season and my retirement and God know what else has derailed us. It's been fun, and I hope to carry it on in person with you for a long time to come.

John: So much agreement, and so much for the mean nasty blogosphere. For my part, I'd like to leave off with a rant about audience. I think one of the things that is killing American arts journalism is our (arts journalists) fogginess about who we think our audience is. Why is it considered more important to bring into the metaphorical tent non-readers who have previously expressed little or no interest in culture? Why is it smart to chase after people who show little inclination to want to engage with the arts, and whom, if they do check you out, are unlikely to return. Meanwhile, those who are paying attention find that the more they know, the less writing there is for them in the local paper.

There are arts organizations that behave this way too. They pander after what they think will get the most people to buy tickets. The artistic product? Hmnnn, not so much. So the product is (thought to be) populist. But luring audiences in by trying to convince them it won't hurt is a low-yield proposition. The audience churn rate is high, and every new production requires enormous work to replenish the theatre to make up for those who aren't returning. Ultimately, these are the arts organizations that fail to find a core audience and always seem to be struggling to stay alive.

I'm not, by the way, trying to make an argument about quality. It's more about who you decide should be your audience.

Arts journalists have to make that decision too. When they don't, readers make it for you. If you're not interesting, then no one much cares what you have to say. If you overpraise, your opinion is discounted, including, paradoxically, by the people you're writing about. I'm not saying abandon the audience who knows nothing about the arts but might be interested if you can hook them. But they should be the second, third, or fourth priority, and since they take a lot of work to cultivate, they should be the luxury add-on to our primary audience.

I'm not advocating for technical obscure insider journalism (though it can be really fun to read when it's done well). This is more a plea for making it interesting and engaging and intelligent; about demanding something of the reader in return. There ought to be some price of admission to this kinds of writing, and it ought to be worth it. I think arts journalists and publications devalue their work when they set the bar for admission too low. TV's 60 Minutes often tackles obscure topics. But they present them in engaging, intelligent ways, they don't dumb it down, and they make you care about the dirty meat packing plant or the crooked garage mechanic. End rant.

To a more pleasant topic (and I've been meaning to clip this in somewhere this week but haven't found the opening). Reading a selection of someone's collected work makes you look at them in a different way. There's something about seeing essays and reviews strung together that gives you insight to how they approach their work. First, I was curious how you decided which pieces to include. The reasons for some are obvious. Others I'm not so sure of, but you obviously put them in there for a reason.

I began reading you regularly when you were primarily a classical music critic. And though you expanded beyond music after that, it made me read your classical pieces (which don't, for the most part, start appearing until well into the book) in a different light. Seeing the classical pieces amidst all the other performers somehow gives them a different context.

The other big discovery in reading the book (and I'm kind of embarrassed to admit it) is your penchant for last line zingers. In so many reviews you take a open-minded descriptive stance that seems to be a reasonable, fair assessment. "Here's what it is, and here's what the artist seems to want to say," you posit. Then that last line comes along and it freezes the whole thing like a snapshot. One of my favorites is your 1974 review of Cleo Laine. You acknowledge she's built a following, describe what she did, then this in the final graf of a four-paragraph review:

"But for this listener, admiration stops a good deal short of affection. Miss Laine strikes me as a calculating singer, one whose highly perfected artifice continually blocks communicative feeling. To me she has all the personality of a carp. But then, obviously, I'm just a cold fish"

It's a brilliant bit that describes your sense of her perfectly. You often close your pieces in this way, as if the whole first section were merely a necessary set up to get to the real frank talk at the end, and I have to confess I hadn't taken sufficient notice of it before. I'm wondering if you set out to write this as a structure or device, or whether it just evolved naturally. Did you have someone early on - an editor, a friend - who helped you find your voice as a critic? I hear so many journalists today lamenting they never had an editor who took the time eo help make them better.

Doug:

I guess we are indeed winding down, since once again I agree with you almost completely about the problem with newspaper cultural covrerage. But why not -- you agreed almost completely with my last posting on that same subject. And of course the Times is part of the larger problem, too, tho insulated by its attention to culture, based in part on business calculation and in part on Sulzberger family values. You ask if my high-culture cred helped me get the pop-critic job in the early 70's. Sure. Today, I would think a little low-culture cred would be helpful to anyone aspiring to a high-cutlure job. And sure, corporate exploitation of boomer trangressive attitudes and music and iconography to sell products is all-pervasive, but it's at least as amusing as it is repellent.

The question of where criticism is headed on the Internet is trickier. It has certainly enabled niche critics to find niche audiences. There is great stuff to read out there, if you have the time and savvy to seek it out. Maybe critics will be more important than ever, given the thickets of imformation to hack through. But the question is indeed how to support them. You say cirtics are "leaving the profession," meaning paying newspaper jobs. But where are they going? Not to the Internet, yet, if they want a living wage. And as soon as the corporations figure out how to make real money from the Internet, through advertising or whatever, they may hire cirtics but they will again impose the same corporate oppression and compromises that prevail in print journalism today.

And I'm not so sure that the proliferation of niche audiences is a entirely a good thing. I'm from the 60's. We valued community back then. Whether the community is a stadium sports event or a Canegie Hall concert (or a Nazi rally, I suppose), there is something exciting about sharing your enthusiasm with the many. Maybe a virtual community can provide that charge, maybe not. But as the audience splinters into niches (remember "demographics," the record-industry buzzword of yore), any illusion of a truly national community (or world -- remember Michael Jackson's "Thriller") imperiled. In the 60's we all thought everyone listened to Bob Dylan and the Beatles; the voices of a generation, and all that. But it was more white college students. Maybe Sam Cooke or Stevie Wonder or Bob Marley was more universal, more of a catalyst for a community. The arts can fulfill individual needs and desires. But they can also bind us together. Does the Internet help us realize that ideal, or threaten it?

John: We're getting close to the end of our conversation, but there are still things I wanted to ask you. One, which you bring up in your last post is about how cultural coverage is pitched. I get that in a mass-culture world the way to get audiences is to try to appeal to a general reader. Unfortunately this has come to mean dumbing down rather than being smart and accessible.

But I think that the strategies that work in a mass culture model actually work against you in a world of niches. That is - as people can choose more and more specifically what they want, they're less willing to accept the blandly generic. Mass culture works because, while it might not totally satisfy all that many people, it's inoffensive enough that many people will accept it when their choices are limited.

The genius of newspapers back when was that they aggregated readers with specific interests. By offering lots of variety, newspapers collected many audiences, which in turn supported the main news-gathering activities.

Somewhere along the way though, the idea somehow became that every reader ought to be able to read every story. Pitching everything at an eighth grade reading level worked for a while. But if you print bland dumbed-down stories about culture, the readers who actually know something about culture are going to be the first to jump ship. Isn't that alienating the very readers you're trying to reach? The problem with that famous A1 NYT Brittney Spears story was not that it was Brittney Spears on A1 but that it was just plain dumb.

Probably every newspaper in America is rethinking how it covers culture as newspapers ride a long slow decline in print circulation. Sadly, the solution at the vast majority of papers is to parade a succession of bland pop-culture features guaranteed to turn off anyone who actually knows something about the topic. This also means that more traditional cultural coverage gets cut back and blanderized.

Good critics are leaving the profession at an alarming rate because the kind of product they're being asked to write isn't interesting to them. And sadly, the dumbing-down strategy isn't working to attract new readers, anyway.

Interest in culture has never been higher. Audiences have never been bigger. Yet outside of about a dozen major newspapers, cultural coverage has been cut back and bland increasingly rules. One of the few places where this isn't generally true is the Times, which has expanded the resources it devotes to covering culture. I realize the Times is in a class by itself as a national paper, but I also assume the paper wouldn't be taking culture seriously if there wasn't a good business reason too. is there something the Times knows about cultural coverage that others don't? Maybe related to that - you were the Times first pop music critic. Is it significant that the paper chose someone for the job who came with high-culture cred?

Lastly - one observation related to your comment about bland corporate culture. I've always found it weirdly fascinating by the way many of America's most established corporations advertise. They try to convince people that if you use their products you're being a rebel or individual or different, when in fact their fare is the most common, least individual and least rebellious. The spirit of the 60s has been corporatized and repackaged and co-opted as an ideal, turned into a Disney ride.

Digital distribution has given people almost infinite choice, and it turns out that they have very individual taste when they're given choices as per Chris Anderson's LongTail observations. Some are asking whether we need critics anymore, when everyone armed with an opinion can express it on the internet. I'm of the opinion that as choices become more overwhelming and information overload sets in, that critics are more valuable than ever. The question Dr. Rockwell, is how do we make a new system that can support them?

Doug: I agree with most everything you say in your last posting (to the annoyance of those, like editors, who value a good dust-up over reasoned dialogue). I do think editors at daily newspapers today prize lively writing and versatile newspaperly skills over expertise in a field of art; they are probably even suspicious of expertise, at least when flaunted. This has a lot to do with the perilous position newspapers find themselves in, and their preferred, business-model- and stock-analyst-driven solution of dumbing down the (arts) coverage and appealing at all costs to the young reader. I seriously doubt most of them know or care about any kind of culture, including popular culture. So instead of smart criticism of movies or rock they go for puffy features about whoever is topping the (manipulated) charts.

When I edited Arts & Leisure from 1998 to 2002, my idea was that while naturally no article should be so obscure or technical that it shut out all but the specialist reader, that there were still clear constituencies for certain kinds of articles. Ballet fans wanted to read about ballet, not necessarily modern or flamenco or opera or movies or rock. And so forth. Thus the idea was to pick writers (we could do that, A&L being largely a forum for freelancers) who loved and cared about their fields, let them keep their own voice (as opposed to bending them to Times style or an individual editor's notion of good writing) and make the weekly package the chorus of all those voices. Rather like artsjournal.com.

As for your question about changes, and social changes, in criticism over four decades: When I was young and trying to get into newspaper criticism, I just wanted a job. As a classical music critic, though I soon realized I loved writing about dance, too, and later rock & roll. Despite all my fancy education, I guess I'm not an intellectual in the sense that I need constantly to probe behind the reasons for how things are. I loved opera and music and dance, and wanted to go in there, hear/see the art and report on it back to the readers, aligning my reactions as closely and eloquently as possible to my perceptions of the actual performance and placing it all in (cultural historical, since that was my academic training) context. I was amused when Phillip Lopate, in his review of "Outsider" for the Dec. 24 Times Sunday Book Review, says I moved on from advocating violent revolution in my youth. I never advocated violent revolution; I was a transformation of inner consciousness kind of guy. I was describing a Living Theater performance in Berkeley and pointing out the incongruity of advocating violence to an audience that had just come from street fighting.

Debates about how you cover culture? Well, 40 years ago there wasn't the panic today in newspapers about threats from the Internet, loss of young readers, decline of advertising and such like. High culture (and movies) dominated the agenda, partly because that was the way it was always done and partly because the publisher was a rich guy who served on local boards and he and his friends expected the opera, the symphony and the art museums to be written about.

It took a while for rock criticism, which really only got going in the underground weeklies in the mid-60's, to penetrate the big newspapers. The Los Angeles Times, where I worked from 1970 to 72, was a pioneer with Robert Hilburn in 1970. None of the big newsweeklies covered rock. When I got to The New York Times in late 1972, rock was still farmed out to lowly regarded stringers. When I became chief rock critic in early 1974, I was still a stringer and still the juniorest classical critic. I came on staff in June of that year, as both a rock and classical critic/reporter. Curiously, in the mid-70's, there was a bubble when the Times rock critic (i.e., me) had enormous influence. The reason was that the rest of the mainstream press and weeklies distrusted the scruffy underground. But when The New York Times, in all its august mainstream majesty, endorsed, say, Bruce Springsteen, he got on the covers of Time and Newsweek the same day. Now, everyone has a rock critic, so the "power" of the Times rock critics, however smart they truly are, is less.

I grew up with the high arts (even though I listened to the Hit Parade in the early 50's and still own a first-edition 45 of "Hound Dog" and "Don't Be Cruel"). I regarded championing rock in the early 70's as a way of loosening up the high arts, of bringing them (and their audiences) more into congruence with reality, with the way music actually was in (North) America at that time. And the way most people who loved music actually enjoyed it, across genres.

Today, corporate culture has so infused rock on its upper commercial levels that blandness has blighted the field. That said, the level of invention in indie rock and world music and independent film (and even, occasionally, top-10 pop and studio features) is livelier than ever. So I am all for a more comprehensive coverage of the popular arts than used to prevail in the 60's. When Howell Raines was blundering into cultural coverage in his blessedly short reign at the NYT (thank God for Jason Blair), he kept talking about "restoring the balance" as he insisted on more and more pop coverage (when he had a hand in it, it was dictated from above and hopelessly unhip). I want to restore the balance, too, but in the other direction. Now my energies would be focused on the high arts, under siege not so much from pop culture as from know-nothing editors and publishers who think that is all they need pay attention to.

A footnote: My whines are directed mostly at the NYT. But of course that paper so dominates the field of cultural coverage in the United States -- in terms of quantity, not quality in any individual case -- that lessons drawn from it do not necessarily correlate to other newspapers around the country. But the same tendencies are everywhere, and need to be discussed and combated.

So, for young critics: Your passion for those arts HAS to remain paramount. Otherwise, you're just a hack. Do you need to adjust yourself more in the direction of chirpy features and personality profiles, as opposed to serious criticism. Probably, if you want a job. Although if you can hang on writing the kind of criticism you want in whatever forum you find, that may still be a ticket to a criticism job at a newspaper; editors have a way of tiring of their own and seeking fancier folk from the outside. Maybe they secretly realize that the very policies they impose stunt the growth of young critics.

I do think there a danger today that more and more young people who might once have aspired to be journalistic critics will gravitate instead to academia or arts management or even publicity. Maybe they'll subsidize culture on the side, by contributing to Internet blogs or forums or chat rooms. Those other, income-producing, arts-related jobs are not terrible ways to live a life. But criticism is still a pretty cool profession, if you can get a chance to do it. And be paid for it.

John: Two huge topics to jump into, both probably worth spending a whole week on by themselves. I'll wait on answering the first till later, since it's such a huge topic. But the second, about specialist critics vs. generalists is easier to take a bite out of.

I don't think being a musician makes one a better music critic or being an architect makes you a better critic of buildings. It helps inform your point of view and that can be useful. But it also might not. I always thought in music school that the teaching of music theory was strangely disconnected from music itself. Sure it might be interesting to understand the rules for resolving dominant 9ths, or be able to perform Schenkerian analysis on a Mozart symphony. But it doesn't necessarily translate into being able to hear more with more understanding or play with more musicality. Indeed, some of the biggest theory geeks I know are dreadfully unmusical; it's as though the balance between sound and structure has been upset. Learning theory is a tool that can inform. But it might not. Most good musicians I know worked out their own ways to understand music; for many, traditional music theory is completely extraneous.

With critics, knowing the technical structure of something can be useful, and if it allows you to write as a kind of "insider" who can explain how it works in an enlightening way, that's great. But if you get too focused on the details it can also make your perspective boringly narrow (a parallel, I think, that also applies in our earlier discussion about how whether knowing artists personally helps or hinders). But a critic does need an authentic base, and having a specialized background can certainly provide that. Unfortunately, lots of critics hide in that base too.

Being a "generalist" doesn't necessarily mean a critic knows less; it's more an indication of a different perspective. Unfortunately, I think the idea of the generalist critic has been greatly abused in American journalism to mean someone who doesn't know very much. There is a great tradition in American journalism that a reporter ought to be able to jump into any beat and swim with the fishes. It's a nice idea, but in practice, at in the arts, it more often results in dumb writing.

I think one of the big problems in the culture sections of many newspapers is editors with no particular knowledge, background or love of the arts. I like to think of culture as an ongoing conversation of ideas. If you walk into the conversation not caring (or knowing about) what's already been said, you're likely not going to have much to contribute.

To relate it to ArtsJournal: the key to doing the site, I think, is being able to know what stories are important or interesting and which aren't. That's not a definitive standard, of course. But you have to know why this story on page D11 in some obscure place is important and this other A1 story isn't. It's the need for a world view that makes a certain sense out of a messy landscape.

One of the big problems with the way arts are covered in this country, I think is that publications rarely think about what their world view is. Being a critic is a lot about making choices and declaring hierarchies. Too many publications make their choices in a haphazard way, and their coverage lacks perspective or point of view.

You are a generalist in the best sense of the word, I think, in that you have omnivorist tendencies and you assume a level of engagement. You write differently about dance because you have a background in opera. You write differently about classical music because you were reviewing the Stones and Judy Collins and Elvis. And no one who reads you over time can have any doubt about what informs your world view of culture. You are a critic with plenty of specialized knowledge; it's one of the things that made your writing on the European culture beat so interesting.

Perhaps your editor was just flattering you, but in another sense, I suspect (hope?) he was voting for a kind of generalism in the best way.

Before I send this back to you, a correction (or clarification, at least) and a question. When I said in my earlier post that there was no such thing as a conflict, I meant it in the transparent sense. That is, not that people don't have agendas - they do - but if as much effort was spent on making those agendas transparent as is now spent on giving the appearance of objectivity, the agendas ultimately wouldn't matter. No one expects Newt Gingrich to be objective when he writes an op-ed, but his point of view might still be worth considering. A writer with too much agenda gets heavily discounted I think, and I think readers still prefer someone who's fair rather than a partisan.

So let throw back your question to you. You started as a critic in a time of pretty dramatic social change back in the 60s. And I can imagine the debates that must have gone on around how you cover culture - particularly that loud scruffy hippie music (he writes affectionately). Now, 40 years later we're in another time of profound cultural change where traditional notions of journalism and audiences and critics are being reinvented. Are there any parallels that link the debates now with those then? And if you were a young critic today, would you change the way you approached your craft? Would you even go into criticism today?

Doug:

I think we're talking about different things with the word "rules." I meant that for each individual, critic or otherwise, there should be no rigid, exclusionary standards that determine our positions about most anything. With conflicts of interest and objectivity, I meant by no rules that to take an extreme position may be fun to write and fun to read, but does not correspond to the way things really are. Life is a common-sense compromise, a solid nourishment to which the wilder passions and polemical positions lend necessary spice.

You seem to be thinking of newspaper conflict-of-interest policies by the word rules. I agree they are often silly and prissy and pompous and contradictory. Though when I was interim classical music and dance critic for the Oakland Tribune in the first half of 1969 (Paul Hertelendy was on a six-month academic fellowship art Stanford), one of my first Sunday pieces argued that the Tribune should pay for critics' tickets, books and LP's. The mad purism of youth. The Tribune killed the column.

But I won't go so far as you do at the end of your most recent post, and argue that "there's no such thing as conflict." Entanglements, unknown or even known, do affect the critic and they do affect the reader. But hey, no rules: everyone has to work out a comfortable place along that continuum for himself. Or herself.

So Doug, I have two questions for you; answer both or one or neither.

The first is born of our shared involvement with the newly reborn National Arts Jounalism Program. Aside from writing criticism or assembling compilations of criticism, how would you best advocate for the imperiled cause of serious arts journalism? And not just the criticism of the higher arts, but serious criticism of all the arts, high and low, Western and world. Would you stress the ideal virtues of Art and the intelligent discussion thereof; or the economic impact of an arts community, including critics, on a city; or education? And to whom? To editors and publishers, in print or the Internet, to bloggers and the public, to North America or the world? What would you do? What should we do? Have a master plan or work piecemeal with funders? Start a journal? Make speeches (to whom?). Write a book? Deluge the Internet with pleas (to whom?).

My second question circles back to my book. In a recent conversation with an upper-level editor at The Times, he said his ideal critic was one who could perambulate around the Culture Dept. or even the paper, writing brightly for the (dreaded, by me) General Reader about classical music or rock or dance or film or sports or widgets, for all I know. Even though this echoes my own career -- I think he was tyring to flatter me -- it made me nervous.

You cited your experience as a musician and a pianist as defining your critical sensibility, nicely making the distinction between that and being a better critic. Of course, knowing the piano and its repertory doesn't help you much with clarinet repertory or the singing voice or the polemics about operatic stage production. To what extent do you think deep, lifelong expertise in one art, or one facet of one art, is the proper goal for the young critic? Or can one jump from art to art, as I have done, counting on one's native intelligence or accrued knowledge to substantiate your competence and hoping that your range of interests will enrich your attention to any one of them? Or do you think there are no rules (like I do!) and that there can be excellent specialist critics and excellent more broadly based critics? As long as the former know how to speak beyond their coterie and the latter know enough to be plausible, even stimulating, to specialist readers?

John: All well and good to say no rules. But we both know that doesn't hold. Indeed, with each plagiarism or conflict case that comes up, the rules at American newspapers get tighter and more reactionary. My favorite over-reach was the Miami Herald's bizarre firing of dance critic Octavio Roca a few years ago when it was discovered that he had plagiarized... wait for it... from himself. He had written about an artist a few years earlier somewhere else, then reused some of the descriptions again at the Herald. This is the kind of stupidity that makes people laugh at newspapers. Perhaps there were other issues at play in this case, but the stated reasons were absurd.

Likewise the ethics about who buys tickets to performances. The paternalistic ethics-addled Seattle Times insists that its critics should not be compromised by free tickets, and so requires its critics to buy every ticket, resulting sometimes in considerable gymnastics by the critics to get the proper paperwork in order.

I agree that junkets can be compromising. But again, if we made clear the biases and then did away with many of these rules, the transparency would be a tonic.

To return to the artist friendship issue, though. I sympathize with the shyness factor. I have felt the same, often. But then, some of the best interviews I have ever had have been when the encounter had turned into more of a conversation than a Q&A. A brief story: I once kidnapped Isaac Stern from the airport here in Seattle when the orchestra wouldn't grant me a time. I found out his flight, showed up at the gate (I was much younger and brasher then) and told him I was his transportation to his hotel. I led him outside to my little low-riding two-seater sports car (like I said, I was younger), and off we went.

I told him who I was, and when we got to his hotel he let me come up to his suite and we spent a terrific afternoon together talking about music and politics (he was interrupted every 20 minutes or so by the phone, as he was managing his empire, and the parts of the phone conversations that I could hear were as fascinating as anything.

When I finally left about four hours later, I had a very different sense of him than if we had just done a traditional interview. He was old and not playing, shall we say at his peak, but I came to understand a lot more about the man because the encounter was not the usual thing.

I've written about his elsewhere, but I like a lot the English approach to covering the arts. It's not unusual at all to see artists and arts administrators weigh in on issues or argue with the critics in print. One doesn't discount their opinions because they run a theatre or opera house. In America it is very unusual to see artists arguing on the pages of our newspapers.

So you say no rules. That's what we have on the internet right now. It does make the reader have to take more responsibility for vetting sources, but I think this is a good thing. I think audiences are much more sophisticated about parsing conflicts than they were 25 years ago. Most young people I know, rather than being oblivious to the manipulations of corporate America, seem aware of them and are appropriately skeptical. It doesn't mean they reject them; just that they're aware of them.

I guess for me it comes down to how it is you develop your aesthetic. I feel that I'm a better music critic because I sat in practice rooms for decades and went to Juilliard and had the experience of performing in lots of different situations. I have a relationship with music that's very personal and based on intimate association. I'm quite confident in my judgments about certain things. When I talk with pianists I feel like I have a pretty good understanding of the terrain they're walking. Does it make me a better critic? I'd say not. It's just the context that drives my opinions. Whether you trust my judgments or not depends on how well I've argued my point of view. That is, being a pianist doesn't give my opinion any greater weight. But it informs that opinion and helps me argue; whether I'm successful or not depends on how I express it.

To circle way back to the topic at hand: knowing or not knowing an artist doesn't in itself make you a better or lesser critic. But the experience of interacting with the artist can help give insight into work. That may or may not make your writing better; it really does depend on the critic. I think publications ought to have strict rules about disclosing relationships, but once expressed, I don't believe there's such a thing as a conflict.

Doug: Glad you're back in action. Are you back in your house? Is your bedroom still under siege? I must say, even without the Great Tree, your place looks beautiful. And look on the bright side (if there ever is a bright side in the skies of Seattle): now you'll have more sun in your back yard.

I like your stirring defense of insider criticism, though if you're so sure of your position, why did you stop reviewing your friend's orchestra, and why are you shy about naming his (her) name? Look: like everything in life, I've come to realize in my weasel-like old age (the fine line between accrued wisdom and bland compromise), rules suck. You yourself say you tread a middle ground, and so do I. Of course "objectivity" is easily debased into a phony balance in which every view, no matter how noble or repellent, must be countered with its opposite. But still, the ideal of a critic who can transcend friendships and entanglements and tell it like it is (like the critic feels it is) is not to be scorned. Maybe objectivity is not the highest goal, but fairness.

As you suggest with your conductor-friend, when you know someone, you may either pay them off with flattering reviews or, if you have a conflicted sense of honor, you maybe treat them more harshly. Either way, you aren't responding to their work but to some combination of their work and their person and your affection for both.

But like I say, no rules. As we age in the world of the arts, social contacts, maybe flowering into friendships, are inevitable You just have to try to do your best with them. Me, despite my belief in contexts and the cultural-historical positioning of the arts within society, I've never felt comfortable knowing artists (except for friends like Linda R. or Helene Grimaud) and have always felt uncomfortable backstage. I even felt uncomfortable as director of the Lincoln Center Festival going backstage and paying courtesy calls on artists I'd engaged before their performances.

Is the following story in my book? It's not at hand. Anyhow, when I was younger, one of my heroes was the Wagner tenor Wolfgang Windgassen. I spent the summer of 1965 in Friedelind Wagner's Master class at Bayreuth (there's an article about that experience in my book). I clung like a spider to the light grid above the Festspielhaus stage for 14 performances of "Tannhauser" with WW in the title role. I never felt inspired (or courageous) enough to go up to him and introduce myself and tell him I admired him. One time I was in a Bayreuth restaurant with friends right next to the table where he was eating with his friends, but no contact. I was shy, or embarrassed. Maybe I didn't' want to spoil my artistic image of him onstage by mixing it up with his real person. Who knows? When he sang Tristan in San Francisco in the early 70's, not long before his sudden death, I finally did manage to mumble my appreciation. It meant nothing to him and it made me feel awkward, but I still admired him then and admire his recordings now. For me, they're the real Windgassen.

Last night I went with Greil Marcus and Bob Christgau and our wives to see Lou Reed's concert performance of "Berlin." (Years ago Reed amusingly attacked Bob and me in a rant on his "Prisoner in Disguise" album.) Not too long ago I was at a dinner party with my wife Linda and him and Laurie Anderson. He spent the whole time talking about his difficulties finding a good contractor to fix up their loft. Maybe he was putting us all on. But it was no walk on the wild side, and that's the Lou Reed I prefer, the "real" Lou Reed.

You ask about how my four-year experience as an arts administrator affected me when I returned to journalism. Well, it certainly offered me insights into how the performing arts work that I would otherwise never have had. Since most of the time I was a presenter rather than a producer, the artists I engaged would come and go without necessarily forming lasting social bonds, though when I run into some of them today -- Kurt Masur, Anthony Russell Roberts of the Royal Ballet, Nicholas Payne formerly of the Royal Opera, Deborah Voigt, et al., we're friendly (if not friends). I'm still tight with my old LC Festival staff, all of whom I hired and nearly all of who are still in place. My biggest production was the 18-hour kunqu opera "The Peony Pavilion," and I remain close friends with its director, Chen Shi-zheng, and with Josephine Markovits of the Festival d'Automne a Paris, our principal co-producer.

But when I came back to the Times, I was an editor (Arts & Leisure), not a critic, and then I was a roving arts columnist, and finally a dance critic. I do have friends from years past in the dance world, Wendy Perron above all, whom I commissioned to do an evening-length work at the LC Festival. But she's now editor of Dance Magazine, so no conflict there. I go back a long way with Trisha Brown (with whom Wendy used to dance), and she and her husband Burt Barr live next door to us. That didn't stop me from reviewing her. I even covered Anna Halprin's "comeback" a few years ago in San Francisco; it's in the book.

But your larger point, that everyone has biases, aka tastes, and that to try to hide them is foolish, is certainly true. Overtly expressed tastes and passions lend a necessary flavor to criticism. I think "Outsider" makes perfectly clear some of the parameters of my own taste. But once again, my no-rules axiom and your middle ground make the most sense. And fairness remains paramount.

When the always amusing, always brilliant Richard Taruskin implies that the early-music movement is only a projection of the present onto the past, he is surely overstating his case. To abandon any effort to find out how things once were, how they looked and sounded and how their creators first heard them or wanted them to be heard, would be sad. That's why I admire the dance reconstructions of Millicent Hodson and Pierre Lacotte and Catherine Turocy. They may be guesswork, more or less, but they're amusing guesswork. We can no more easily toss aside a pursuit for historical "authenticity" as we can abandon the ideal of journalistic objectivity. They may be phantasms, but they're seductive ones.

Okay - we're back online. Power has been restored here in Seattle (I understand as many as 1 million people had electrical outages). The tree that met the acquaintance with the back of our house was the most impressive tree in our neighborhood. It was more than 100 years old and the trunk is wide enough to require two people linking hands to circle the base (if you were inclined to do such a thing). It is a crazy puzzle tree, with massive trunks going in all directions. It was always an unlikely bit of geometry, but it was magnificent. The arborist told me that it had been topped incorrectly about 70 years ago and that caused it to sprout dozens of new limbs and embark on its eccentric paths. The house looks to be mostly alright, amazingly.

John: I did see your note in the introduction the about inside relationships between critics and artists. And I particularly enjoyed the Linda Ronstadt piece in which you struggled with the idea. You're a fan of hers, didn't understand why many other critics didn't/don't share your enormous admiration, and were torn between your role as a critic and the fact that you had gotten to know her personally. You confessed in the essay your friendly relationship with her, wrote one last ringing argument as to why she's great, and then never wrote about her again in the Times.

I think this issue is a good example of a major weakness in American journalism. The ideal is supposed to be objectivity, and newspapers jump through all sorts of hoops to try to suggest they are. Nonsense. The idea of objectivity is a thoroughly discredited notion at this point, and American journalism's defense of it is ridiculous. Everyone has biases. Every institution is built on biases. Instead of pretending they're not, they should declare them and move on. Make clear your observation point, make the argument and your reporting is stronger, not weaker.

Instead, what we have in American journalism is a false construct in which we have to wedge every issue into a "both sides" continuum, even when it's clear sometimes that one side of an argument isn't credible. This elevates a kind of false debate and I think damages the way in which we're able to discuss serious issues in this country.

This faux objectivity is even more ridiculous when it comes to critics (though with much less serious consequences). Joe Horowitz argues that an interesting opinion is an interesting opinion and ought to be heard. But American journalism is paranoid about the appearance of conflict of interest, and so the range of opinions is narrowed considerably.

Still - I know critics who are friends with many of the artists they cover. And I know critics who studiously avoid any personal relationships with artists. I probably walk some middle ground. I have a conductor friend who claims that as soon as he started to get to know me, my reviews of his orchestra became more critical. I hope that's not true, because I did try to be honest in my reaction. But as soon as we really became friends I stopped reviewing his orchestra.

I think the current policy on this at most American newspapers is the worst of all worlds. Name me a critic and if I read them for more than a couple of weeks I can come up with a list of their biases. This isn't a bad thing. Look at Frank Rich's theatre reviews and it's unmistakable where his passions lie. That doesn't mean that the musicals he didn't like were awful, it just meant they didn't speak to him. If you were a New York producer while he was the Times critic putting on the kind of show you knew he wouldn't like, you knew he was going to attack.

An analogy in classical music might be the early music movement. The thousand-strings Baroque sound is dreadful to someone who likes the pared-down aesthetic. I can make arguments about the merits of both sounds, but I enjoy an impassioned argument for one side over another. Apply this to orchestras - if you don't like the sound of the New York Philharmonic because you just don't like the way it sounds relative to the Philadelphia Orchestra, then everything you have to say about the New York Phil is going to be colored by that.

Take it a step further and if you're not a Maazel fan, then probably nothing Maazel does is going to please you. If you're a Tilson-Thomas fan, then everything the man does will be processed through this bias. None of this is bad; a critic's experiences and taste and resulting prejudices are what make him interesting. Or not.

Okay, last step (and I know you already know I'm going there). Your friendship with Linda or Ann(a) gives you the possibility of having a perspective on their work that most critics don't have. Some will discount your assessments because of it, but I think if the relationships are declared, the potential benefits far outweigh the negatives. When applicants apply for a job or students for a school they get recommendations from people they know, people who can supply insight. Prospective employers/schools obviously find this valuable, even knowing the pre-existing relationship. Having sat on a few search committees, and can say that the perspective of someone you knows a candidate well is sometimes fae more valuable than an assessment by an "objective" source who doesn't really know the person well.

Readers are sophisticated enough to account for personal relationships if hey know about them. It's when they're unrevealed (as the current system promotes as a convention) that it's a problem. I wonder - did you find it difficult not to write about Linda afterwards (or other friends)? More broadly, did you find it diffiult to slip back into the journalism side after running the Lincoln Center Festival and forming different kinds of relationships on the other side of the curtain? Also, I'm interested in whether you found people talked to you differently while you were an administrator than they had when you were a critic.

Doug: I hope you got some sleep and are dug out, as it were.

As for audiences: I agree, sheep-like behavior masking a lack of conviction is bad however it's manifested, and if today it's manifested as automatic standing ovations, we're agin 'em.

As for my hippie roots: I was never a real hippie, whatever my parents thought. I was too busy studying (or not) for my Ph.D. orals, writing my dissertation, going to the opera and rock concerts, doing radio programs, seeking love (or its carnal equivalent) and dancing with Ann(a) Halprin, tho some of those latter activities shaded into hippiedom. I admired the 60's, I was swimming in the Berkeley variant of hippie culture, and so of course it had an impact on my sensibility --a profound impact. Which I make clear throughout "Outsider," capping it off with the final article. I was always more a sex-drugs-and-rock-&-roll hippie than the harder-edged political variant into which the Free Speech Movement morphed under the weight of Vietnam and which prevailed on the East Coast. Northern California -- in music and dance especially -- shaped my ideas about the arts more than the trappings of the hippie lifestyle, which even then I found a little suspicious. In particular, Ann's ideas about dance and Lou Harrison's music made their mark. And the sweeping optimism of so much of that time's rock. We all feel nostalgic about our youth, but the conjunction of the 60's and my own youth was pretty heady.

(See my introduction to a forthcoming University of California Press book about the San Franciso Tape Music Center and also, from what I've heard, Janice Ross's forthcoming book about Halprin.)

In looking over my selections for "Outsider" (and some will be thrilled, others daunted to learn that there's material there for another 10 or 20 books of equal length, not that the clamor from readers or publishers has as yet become deafening), I'm surprised by how much dance there is from my California days. Maybe I was stacking the deck since I am now (for another three weeks) a dance critic. Maybe I wanted to beef up my dance bona fides. But there ere other, better explanations. I was a classical music critic then, and classical critics were expected to do dance. But I took to dance: its tactility appealed as a source for writing, and I really loved a lot of it (and was dancing myself, in Ann's hippie-ish, naked way). In Los Angeles my boss, Martin Bernheimer, felt he should cover the big touring ballet premieres, but otherwise I had a pretty free rein. Conversely in music, I got mostly second-tier concerts, which seemed less interesting when it came time to pick what would be in "Outsider."

Changing the subject: In my introduction I try to explain why I called this compilation "Outsider," which has seemed odd at the outset to a number of readers, given my sequence of insider jobs at big-ticket institutions like the LA Times, the NYTimes and Lincoln Center. I offer various reasons, but I'm curious about your take on the last one. Have you given much thought to the question of how distanced a critic should be to those he/she reviews? Clearly there are advantages to being friends with artists, hearing them discuss their work from the inside, trying as hard as possible to dig deep into the assumptions and technicalities of a scene, trying to claim ownership of an artist by becoming his/her champion. My metaphor for that is Hanslick playing chamber music with Brahms. But there are also advantages to holding oneself aloof, to knowing as much as possible about the art and the artist but maintaining an "objective" (in quotes because of the inherent absurdity of that aspiration), outsider stance and trying to serve the art and the readers and your own aesthetic as well as the artists. Where do you come down on this distinction?

Doug: Geez, with all due respect to Art, I would think a tree, a storm, a roof, power and family safety might just for the moment trump this conversation. I'll respond to the rest of your 3 a.m. posting in a bit. Looking forward to your next message, but take care of priorities!

John: I had a response all but set to publish tonight when suddenly there was a huge crash and a 60-foot cedar from our neighbor's yard toppled down and smashed the back of our house. Unfortunately there's still about a third of this huge tree standing over our house, there's a major wind storm blowing, and the entire neighborhood is without power. Plus we've got flooding in the basement. Afraid that the rest of the tree will fall right on our bedroom, we have vacated to a nearby motel, where I am tapping this out in the bathroom on my laptop while the family sleeps. So where was I?

I myself was not attacking ovation inflation. I see nothing wrong with it, actually. I don't stand myself because I guess I'm just not that demonstrative, but I don't care if others are. I was just wondering if it signals anything about the modern audience that's different from ears past. You write that:

Audience timidity about strongly expressing opinions might seem contradictory with a disdain for standing ovations; sitting and applauding politely is hedging your bets; standing and cheering puts you out there, in some sense.

I'm not sure that I agree with that at all; in fact it may be the opposite. Standing and cheering might be the safer gambit in a group that's doing it. Look, I'm not advocating for full-on criticism, only that the engagement be real somehow.

You brought up the 60s, and I had meant to ask you about those early reviews of the hippie happenings in California and what effect you thought they had on your later writing. In a way, I was thinking as I read the book, your (sometimes bemused) accounts of these events and openness to them being whatever they wanted to be established a tone that carried on when you went on to write about pop and classical music in New York.

Okay - there was more in the first version of this post, but it's getting on to 3 AM and I'll pick it up tomorrow (er, later today)

Doug: The issue of audience sophistication and naivety is bound up with the democratization of the arts. The ideal, for those who believe the arts have been dumbed down by yahoo audiences (meaning rubes, not subscribers to that estimable e-mail etc. site), is of a Leo Straussian elite, guardians of the refined secrets of art surrounded and threatened by a roiling mass of dopes who can never be expected to appreciate the Finer Things. Who offer standing ovations as a Pavlovian response to most anything. And who wait for the authoritative voice of the critic before daring to offer any opinions of their own.

The trouble is, elites of taste and class and wealth are not the same. The Archbishop of Salzburg was an aristocrat, and he made Mozart's life miserable. On the other hand, Louis XIV was (in his less corpulent youth) a dancer who more or less invented ballet, and Frederick the Great, when he wasn't slaughtering innocents in his wars, played the flute and composed. Rich social climbers have always been a source of mockery: Monsieur Jourdain was rich, and hence of the elite in the same sense that Donald Trump is, yet he stands as a symbol of Philistinism.

I come out of the 1960's, as anyone who spends enough time with my book will see is embedded in its sequence of articles: hippie stuff at the beginning, a nostalgia for the 60's at the end, general subversiveness throughout. I was a rock critic in the 70's in part (the main part was loving the best rock music) because we believed back then in the democratization of the arts, that only a ruddy influx of populist energy would purge the higher arts of preciousness and academic self-absorption. Of course, that didn't so much mean a newly vigorous response to Mozart as a new kind of popular music worthy of the ruddy populists.

Of course, as I discuss in my introduction, it didn't work out in quite so sanguinely. There is terrific popular culture out there today, in music, films, television, video games, graphic novels and the like. But there is also a lot of crap, worse yet corporately dictated crap, originality having been bled out of the product to fulfill commercial formulas. They don't usually work, those formulas, but that doesn't stop the suits from trying.

In the meantime, for all the laments about the dearth of exciting composers, choreographers, conductors and soloists, and for all the periodic collapse of this orchestra or that ballet troupe, the high performing arts are booming. Yet the boom is more quantitative than qualitative. More and more people attend such events, but they persist in standing up like marionettes whenever they can.

In one sense, disdain for standing ovations seems a little snobbish. Rituals change. I can remember being surprised when the concertmaster came out before the conductor to garner applause before settling down to tuning the orchestra; it seemed a little vulgar. Now Americans, at least, stand. I heard a wonderful concert in Paris Monday night. The audience loved it but expressed its enthusiasm with prolonged applause and rhythmic clapping; not a soul stood, except to leave. But I'm not sure that means the Paris audience was more sophisticated than one in, say, Seattle or New York.

Audience timidity about strongly expressing opinions might seem contradictory with a disdain for standing ovations; sitting and applauding politely is hedging your bets; standing and cheering puts you out there, in some sense. Anyhow, the complaint is old hat, and has prompted all sorts of pundits high brow and middle brow (the dreaded Siegmund Spaeth, the laudable Leonard Bernstein) to undertake musical education for the masses. Whether people are shyer now about voicing their opinions than they used to be, I'm not sure. I keep trying to tell people that critics are part of a conversation, the same kind people have in avid groups disputing one another's opinions at intermissions of operas and concerts and dance performances.

As for you, Doug, you probably sit because you're still a critic at heart and critics are notoriously grumpy about evincing enthusiasm in public by anything so vulgar as applause, let along standing ovations. And maybe you occasionally do stand either because you want to see what's happening on stage or because impatient people sitting toward the center of your row are pushing past you to get to their cars and babysitters. Or maybe, very occasionally, you love something so enthusiastically that you can't sit still in your seat.

If, however, people feel freer to express themselves about pop culture, maybe that means they are intimidated by the classics (a solution: more education). Your theory about their being freer to express themselves because pop culture is everywhere, devalued by ubiquity, seems spurious to me. There is still classical music on the radio and the Internet, and CD's (despite the demise of Tower) are still easy to come by. Maybe people freely express their opinions because the popular arts, which generally involve brand new creation, are more exciting and impassioned than safely historicized classics have become.

Greg Sandow is not alone. Everyone I know in the institutional end of the performing arts is busily reaching out to the young, the disenfranchised and the poor. A good plan, though it may lead to an influx of the very yahoos who persist in standing to cheer. The best lure to the young or the poor is cheap tickets. Frank Castorf, an old leftie who runs the Volksbuehne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz (mostly for spoken drama) in the former East Berlin, would only accept his contract if the Berlin city fathers guaranteed him a subsidy that would allow him to peg his ticket prices at the exact same level as a movie. Last time I looked, his theater was packed.

Enough for now. Do you yourself feel a victim of lassitude about, say, classical music? Are there performances in Seattle that regularly thrill you? If not, maybe you need to broaden your tastes and accept popular art not as some easily dispensable product but as a source of real creativity. If so, maybe you should accord them a standing ovation.

John: Point taken - I'll try to focus this entry on more or less one idea. The other day I was a guest on a CBC radio show as part of a panel talking about "applause inflation." Of course it does seem that all anyone has to do anymore is walk on stage and get off without tripping over themselves to earn a standing O.

Some people are upset that audiences give it up too easily, that their standards have slipped, that what used to be reserved for special occasions is now demeaned by over-use. Now, I have to confess I'm one of the stubborn sitters and don't get to my feet very often, but I do feel sometimes that I have to bend to the group breeze and rise.

I do think that the fashion for standing after a performance has come to mean just that, a fashion that shows general appreciation. Can't we all just get along? But I wonder if this is some evidence that the way people relate to live performances has changed in recent years. The auto-stand isn't just happening in out-of-the-way places; you see it at Carnegie Hall, too.

I don't often hear many engaged conversations about a performance as people are leaving the hall (or intermission or afterward). And if you try to strike up a conversation with the average audience member (whoever that is), you tend to get generalized, safe impressions. It often seems oddly detached, safe.

It seems like more people are reluctant to express passionate specific opinions about the traditional performing arts. Yet, ask them about movies or pop music they listen to, and suddenly everyone's a critic; they become animated talking about why they "loved" this or "hated" that.

I think that it's because people consume music and movies in easy-to-get quantity. They have personal relationships with movies and TV and music because they can access it almost anytime, anywhere. And they feel secure in their ability to judge what is good and what is bad because of those relationships and they aren't afraid to express it.

People used to have this kind of passionate relationship with live performance, but I wonder if most (and even a lot of critics) are not confident enough anymore to stake out strong opinions. What does this mean? Is it easier to have a relationship with your MP3 player? Are people too intimidated to presume a strong reaction? It's certainly more predictable (safe) when you have control over it.

This growing public detachment about traditional art is a problem. I think younger people who are growing up with this amazing access to entertainment have different expectations about the artists they choose to engage with. It's a more interactive dynamic than the traditional I perform/you listen mode. Newspapers are grappling with this problem. Disney's grappling with it. Anyone who makes anything has to rethink how they're going to interact with people. I think many traditional "content producers" are clueless about this new dynamic. Critics too, for that matter (present company excepted, of course).

Doug:

By actual count there are 4,217 really good ideas in your five paragraphs. Well, maybe one or two less, but they're all piquant and deserve response. Here's a start:

Just as artists resent others laying their taste/biases/criteria on them, so might critics object when artists (or their enabling presenters, and I was one of those too) want the critics to genuflect before their own taste/etc.

Artists are entitled to make art any which way. Critics can respond any which way, though art is more important than criticism and thus that artists should in some sense lead the dialogue. A critic isn't much good if he/she (oy, political correctness) can't tell readers what it was they saw.

It would be nice to sync up the dialogue, to conduct on fully shared terms, but that would require length, conversations between artists and critics before and after the event, and that's neither practical nor necessarily ideal, if the critic is to maintain some kind of independent voice.

There are few rules in this game. Critics and artists and everyone else who loves the arts (audiences, presenters, funders, etc.) are part of a conversation. Critics in daily newspapers may have a louder voice than some others in that conversation, tho their amplitude has been helpfully diminished by the rise of the feistily independent (or sometimes downright bitchy and mean) voices on the Internet.

There are few rules in this issue of contextualization, either. I'm not sure I quite buy your distinction between me and Anna Kisselgoff; I think we both tried to draw conclusions from the dance itself as well as from the surrounding context, though your description of our basic tendencies seems right. I just wrote a review (in the Dec. 14 NY Times) about three dances in Europe based on operas. I suppose another critic would have dug deeper into the essence of the choreographic styles of Sopheline Cheam Shapiro's Cambodian dance "Magic Flute" or Johann Kresnik's "Ring" or John Neumeier's "Parzival." I put them in context, of their own careers and of the relationship between their dramaturgical scenarios and the operas. Another critic would have done it differently, or not sought out the grouping of these three performances in the first place.

Every decent critic has a voice, just as every decent artist must. My voice has been shaped in part by the particulars of my education and professional career. I was trained as a cultural historian. Part of my junebug-like jumping from art to art was a true reflection of the breadth of my tastes, and I've tried to portray that breadth in my "Outsider" compilation as a virtue, which I think it has been. Part of it was born of serendipitous accidents of a career -- the good luck to be in the right place when the Times needed a rock critic, the tempting offers out of the blue, like Lincoln Center or Arts & Leisure or dance -- and part of my changes were driven by failure (going to Paris as European cultural correspondent when I didn't get the chief classical music critic job in 1991). Joe Lelyveld, who denied me the classical job and sent me to Paris, has always said he did me a favor. Who knows? Two roads forking in the woods and such.

Anyhow, basta for now. Just out of curiosity: what are the stunts Beethoven pulled?

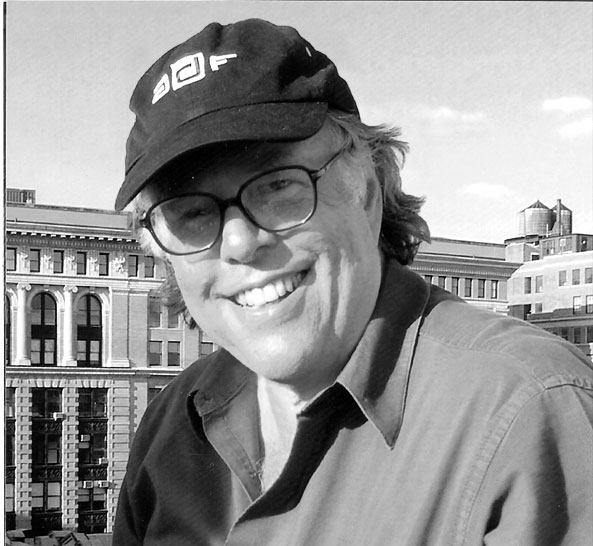

For the next week, critic John Rockwell will be joining me in a conversation on ArtsJournal. John started working at the New York Times as a critic in 1972, and is currently the paper's chief dance critic. He was also the paper's first pop music critic, wrote extensively about classical music, invented a "job" prowling the capitals of Europe and writing about what he found interesting, and edited the Sunday Arts & Leisure section. For a few years in the 90s away from the Times, he ran the Lincoln Center Festival. In a few weeks he'll be retiring from the Times. His latest book, Outsider, is a collection of his writings on culture since 1969.

John: A few years ago, the artistic director of a presenting group here in Seattle got pissed off by the reviews the dance groups he was bringing to town were getting. He (brashly) wrote an open letter to the press in which he excoriated the critics for trying to impose their sense of the history of the field onto the experimental pieces he was bringing.

His contention was that the vocabulary his people were working in had changed (the whole does-this-theatre-piece-even-look-like dance thing) and that it was unfair to try to contextualize it with a set of criteria he thought didn't apply anymore. While I was in sympathy with his judgment about the usefulness of the reviews he was getting, I thought he was off the mark in his analysis of the problem.

Nevertheless, it seems to me that the context and criteria problem is huge right now, and not just for critics. As it gets easier for artists to distribute their work, it becomes easier to attract niche audiences and build a constituency for your art. Consensus about what's good or not seems more and more difficult to achieve. And even the definition of what constitutes consensus now seems problematic.

It seems to me that insisting on absolute standards is a long discredited notion. Beethoven was a blasphemer for some of the stunts he pulled, yet the standards grew to celebrate him. Robert Wilson is a self-indulgent infuriating poseur to some, yet he finds collaborators among blue-chip artists and audiences among many with sophisticated tastes.

So I guess I'm wondering about this whole notion of quality and by whose definition of same. Your approach to writing about dance, for example, is very different from that of your predecessor at the Times, Anna Kisselgoff. Hers was a more technical focus, and she honed in on specific parts of the performance she thought put it in context; what I mean is that that context always seemed to be drawn from within the artform. You, on the other hand, tend to take a broader view, and often make your points about a performance drawing on some outside context. I know this has been controversial among many in the dance community. I think that all critics find their audience, but I suspect you both appeal to different audiences. Each of those audiences has different expectations. The field of criticism has changed enormously since you started back in the 60s (another period that was challenging notions of quality). Do you think we expect different things from critics today?

I'm going to stick for now to the mixed stories on the main page. I think it provides an easier scan of what's been updated, and anyone looking to see stories by topic can click on the topic link. Those links are across the top of the site, and they also link from the topic tag that runs with every story. Really easy.

The new rss feeds are almost ready and will be implemented sometime in the next day (and they'll offer full text of blurbs and are organizeable by topic). I'm still working on fixing broken links etc. I hope things will be mostly done by the weekend. Oh, and all that white space at the bottom of the site that some have been upset about? In the weeks and months to come, it will be filled with new features. It'll be worth the wait, I promise. Now on to something much more interesting and that has more to do with art.

Special Guest Blogger

For the next week, John Rockwell will be joining the blog for what we hope will be a wide-ranging conversation about the arts, arts journalism, and him. John has been a longtime critic for the New York Times, and he's leaving the paper ("retiring," he claims) at the end of this month. Coinciding with his departure from the Times, he's got a new book out - Outsider - which is a collection of pieces he's written since he was a cub critic in Oakland in the 60s. It's a fun and revealing read.

For the next week, John Rockwell will be joining the blog for what we hope will be a wide-ranging conversation about the arts, arts journalism, and him. John has been a longtime critic for the New York Times, and he's leaving the paper ("retiring," he claims) at the end of this month. Coinciding with his departure from the Times, he's got a new book out - Outsider - which is a collection of pieces he's written since he was a cub critic in Oakland in the 60s. It's a fun and revealing read.We haven't really worked out a form for this discussion, but it will start later today, after John gets off a plane from Europe. Hope you'll look in on us.

New News Format

The first thing you may notice is that the traditional AJ news section is no longer segregated by topic on the home page. Insted, each story posts in the order it was added, and carries a tag for the topic area. This will make it easier to see at a glance what new stories have been added since your last visit. And it returns to the original AJ format where the stories were jumbled. My original idea for AJ was to mix up the stories so readers could stumble over unexpected items. We also now have at the top of the site a "current top story" section. Previously, big stories were often hidden far down in the site in their topic section.

I realize that many of you come to ArtsJournal for only one category of story - music, or visual arts, or dance... If that's the way you want to continue to read the site, click on any of the topic links on the ribbon across the top of AJ and you'll see the stories collected by topic. And, for those of you who prefer to read just the headlines, there's a page where you can see all stories by headline only. If you miss a day, our "previous days" page displays the last five days of postings.

The new site doesn't offer permanent archives. This is because the search function is greatly improved. Search results take you directly to the blurb you're looking for rather than just the page where the search word was found.

Arts Video

We'll also feature a new arts video every day. Just click twice on the video window and it should play. We are only archiving the most recent ten days' worth of videos.

AJBlogs

We now have 18 arts blogs on ArtsJournal, and they get greater prominence in the new look. There's a running list of the most recent posts from all AJBlogs as well as a section that features some of the best postings from around the site. There's a new central blogs page listing blog posts. In the coming months AJBlog Central will be changing and expanding.

To Come

Not all of our rss feeds are built yet, so please be patient. There are also some links and features that aren't fully functional yet, but they will be fixed in the next few weeks. If you have comments, complaints or suggestions, please let me know.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City