main: April 2010 Archives

Here's a little taste of the article from the Sun Sentinel:

Here's a little taste of the article from the Sun Sentinel:Several board members questioned why the district was cutting some elective programs but not cutting the salaries of those who administered the programs.You may note that the arts are electives. Other places describe them as non-core; still others call them extracurricular.

Some librarians as well as art, music and physical education teachers have been asked to cut their programs -- and salaries -- to 53.3 percent, working 20 hours a week and maintaining benefits, to save the programs.

I was recently told that the new New Jersey Commissioner of Education found it hard to believe that the arts are a core subject.

But wait, there's more: In preparation for the 50th Birthday of the New York State Council on the Arts, Governor David Paterson has proposed to a gigantic cut in the agency's budget:

An approximately 40% cut in local assistance funding, from $41.6mm to $25.2mm.

A 12% cut in the administrative budget, from $4.84 mm to $5.49mm.

Here's another way of looking at it:

.New York State¹s per capita spending on arts would drop from $2.48 to $0.77

Caracas, 13 de Abril, 2010

Having been so blown away by the rehearsal of the Simón Bolívar orchestra the previous Friday (see Part Three), and totally involved with planning these Young Composer classes, one might excuse me if attending the concert of the Mahler 7th Symphony this Tuesday evening would be somewhat of a let-down.

But no. Even though Richard Mannoia was totally ill and could not attend, even though I myself was exhausted, this turned out to be an evening to remember for the rest of my life.

First of all, you have to appreciate this: Attending one of these concerts at the Teresa Carreño Theater puts one in the middle of an unmistakable atmosphere of celebration, liberation, and national pride. As I'd said, the theater was recently liberated from its political-only bondage. Before even arriving at the gate, we are besieged with vendors hawking photographs, recordings, memorabilia of the Simón Bolívar orchestra, of El Sistema, and of course of Gustavo Dudamel, a national hero. Sound familiar? Hellooo: Like a rock concert, a Yankees or Red Sox game, an event which excites public passion.

The atmosphere tingles with expectation. Dani Bedoni, our incredible friend (words fail) apologizes that the seats are not the best. (They are the best, but never mind that.) The concert begins a bit late, and the audience starts up several times in impatient applause. It appears to me like an expression of eagerness, rather than annoyance, since, well, lots of things start late around here.

Finally, the orchestra streams onstage, all 100 of them, as actors in a great drama, beaming, heads lifted in pride. Applause greets them, and then the concertmaster, Alejandro Carreño (Yes, a descendant of Teresa Carreño, one of Venezuela's first great composers, but more of that later). At last, Gustavo Dudamel, to thunderous applause.

Now, I know this symphony well, having performed it with some of the great conductors over the years. Words are going to fail badly here, but suffice it to say that my overall sense of the core of it is of darkness, forcefully moving toward light and victory, but of many quick and inexplicable jolts of mood, heavily fraught with the history of the German struggle and Weltanschauung. How is it possible, then that this conductor, not yet 30, with a junior orchestra of kids, really, many of whom probably know little of the course of German culture or philosophy, literally bring Mahler to life right in front of my eyes, ears and soul? How is this possible?

I almost cannot sit in my seat. I am in tears the entire performance. I'm fleetingly aware that I'm glad no one is sitting directly behind me, I don't want to annoy anyone. But I am in a different world. My world, Mahler's world. This is why I became a musician. The technical accuracy, the joy, the grasp of the mood swings by Gustavo - never showy or in any excess, yet exquisitely planned, convincing utterly. The cellos straining mightily to express to us the depth of their sorrow and passion, The tenor tuba, alone in its eloquent orations, heroic, tragic, thougthful, youthful.

OK, the words do fail. But the music does not. It is conveyed to these people in its eagerness, its virtuosity, its honesty. The applause is long and thunderous. These are heroes, giving us pride, beyond national pride, the pride of having done something human and good.

On a more worldly, professional level, one may well ask how an orchestra such as one of the top El Sistema orchestras compares to the traditionally great orchestras of the world. An unfair question, really, but one that will be asked in any case. First of all, I am anything but an objective observer. The experience of great art and music is my life. I would never take anything away from the sheen and polish of the great symphony orchestras; the magnificent soloists and section leaders, the lush sounds of masterful playing of all the members, the depth and sweep of the repertoire: all this is the achievement of centuries. The greatest orchestras are incomparable--I know because I've played in one of them most of my adult life.

But nothing in this life stays the same. Here in Venezuela is being born a new spirit in the symphony orchestra. And well would we do to celebrate it. Members of the Berlin Philharmonic are streaming down here constantly to teach, yes, but also to learn. The same for the other great orchestras of the world--and now the New York Philharmonic. As we leave, Sir Simon Rattle arrives. Then Claudio Abbado. Yo-Yo Ma. Wynton Marsalis. The list is dazzling, exhaustive. Deborah Borda of the Los Angeles Philharmonic sensed the energy here early on, and famously woo'ed Gustavo up to the LA Philharmonic. I say: More power. We all benefit from innovation. Likewise, the great innovators of Music Education (now in capital letters!) from Eric Booth, Mark Churchill and Anne Fitzgibbon to Tom Cabaniss, Sarah Johnson, Jennifer Kessler, Ted Wiprud and so many others from the U.S. and Europe have either come down here multiple times, or sent representatives. Mark Churchill's Abreu Fellows are already becoming legendary.

14 de Abril

Speaking of innovation: Back to our Young Composers classes! We are making headway today: music is proliferating among our pioneering students. Both Dani and Diana are here, and along with Richard, Rosa and Pedro, we are circulating among our composers, working with voice, instruments, keyboards. It also occurs to me that we should be recording their drafts. Gabriél and David are clearly advanced in their thinking, yet are struggling with notation. Are they really hearing what they are writing? Apparently so, but are writing in a linear way, instead of vertically, as a score. Am i getting my point across? With two days left to go and over two dozen children to care for, this is daunting. I'd asked for a young professional student of mine, Micah Brashear, to join us, but it was decided that the staff was sufficient as it was. Now I wonder. There are so many things that simply cannot be predicted, here on all sides, that it is really amazing we've gotten this far. Everyone wants this to succeed, but what exactly is the measure of "success?"

The next few days will tell...

--Jon Deak

Click here for Part Seven

***************************************************************************************************************

Jon Deak, born in the sand dunes of Indiana of East European parents, is a Composer, Contrabassist, and Educational pioneer. Educated at Oberlin College, the Julliard School, the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (Rome) and the University of Illinois, he joined the New York Philharmonic and served as its Associate Principal Bassist for many years, while continuing his professional composing, and studying with Pierre Boulez and Leonard Bernstein. During this time he also introduced ground-breaking performance techniques for the Contrabass, and in his orchestral writing, working with major orchestras across the country.

From 1994 - 97 he served as Composer In Residence (sponsored by Meet the Composer) with the Colorado Symphony under Marin Alsop, which is where he initiated the public school program now called The Very Young Composers (VYC).

With support from the New York Philharmonic and others, the VYC has grown steadily, winning a national award for excellence in 2004. The program has been introduced in Shanghai, Tokyo, and now in Venezuela, besides serving hundreds of children in eleven New York area Public Schools and such places as New England and Eagle County, Colorado. The New York Philharmonic has premiered 42 works for children, fully orchestrated by the children themselves, mostly under the ages of 13, as well as hundreds of chamber works in the public schools and libraries.

***************************************************************************************************************

Daniela Bedoni, Guztavo Dudamel, and Jon Deak

Daniela Bedoni, Richard Mannoia, and Jon Deak with children from El Sistema

By Jon Deak

April 10, 2010

Hola Dani -

You had asked me a very good and pointed question: "If you say that the children can already compose, then what exactly do you give them in your classes?"

So, just to make things clear, I do want to give an answer to that. But first, we must recognize that all children are different, and that they have different needs to be addressed in order to speed them on their path to creativity. Still, there are basic needs and challenges that many of them share. And for that, we strive to provide them with the following: (Sorry if I write in English, it's quicker.)

1) We provide live instrument demonstrations that are interactive! We believe in the profound expressive fundamental nature of the instruments of the orchestra, the human voice, and folkloric instruments. To help them come alive, we try to give demonstrations whereby the student "interviews" the instrument, asking it questions, listening for the answer, and where possible, it is performed. Thus they develop a relationship to it, rather than being told how to write. At all times, we celebrate and respect the Young Composer's voice.

2) Rhythmic games and exercises. These are intended to draw out the rhythms that are within the child. This works well in social settings and class groupings. We build up a feeling of teamwork, as well as an awareness of rhythmic layering as a prelude to melodic layering; instruments and voices working together, building, fighting--whatever images naturally arise from the children. Dance rhythms are encouraged, as well as the student changing rhythms where he or she chooses. Nothing is set in stone.

3) General respect for the efforts and ideas of one another. As in the above, we encourage teamwork, mutual support, and respect for each other as Artists. There is no talking or distraction when one composer's sketch or experiment is being tried by the instruments, and most certainly at the concert, where we all applaud the successes of each other.

4) The Ear Fantasy, or the Sentiments of the Chords and Intervals. In most societies, we grow up listening to harmonic, even contrapuntal music. It is true, that in some societies, most notably China and India, children hear monophonically, and we respect that. That being said, we need to give children access to the harmonies that their ears are already hearing quite well, and in great detail.

In that regard, I've taken an idea from Leonard Bernstein: that it is important for the child to feel the sentiment of a chord or an interval, more than its technical name and rigid rules of use. So we give the children basic chords which they identify according to the individual feeling (which is almost always a bit different!). A major triad may sound: happy, clear, sunny, or even glaring and sickening. A diminished triad: spooky, scary, sad, or even scratchy, furry or purple. And so on. A melodic minor 7th: yearning. A series of minor 2nds: like a beehive, or an argument. Then, we ask the children to invent or discover their own chords. The class is repeatedly asked to remember which chord is which, as a kind of game/test. Kids catch on at very different rates, which matters little, and all are encouraged. It is so important that from the very start, they "own" the chords they use.

5) Basic score notation. One of the principles of VYC is that notation is a tool, not a requisite for a composer. After all, there are blind poets! What's important is the music in the child, not what they write on the page. So while we, in some classes, are able to demonstrate the basics of score notation, even then we insist that the pitches, rhythms, dynamics, articulations, timbres, tempi, are all checked by our teaching artists against what they hear the child is producing and if what they sing, hum, tap or play is different from what they've written, then we change the score, not the child's conception. We even generally insist that a given passage is demonstrated three times by the child, so that we're sure that what is written is really the truth. If we force them to write everything, then what we get are white-key quarter notes. In other words something very, very far from the truth of what the child is really composing.

6) Musical form. Again, we do not introduce Rondo, Sonata, Fugue, or even A-B-A form. We do not tamper with the flow of their ideas. We do encourage development, however, on the models of ordinary conversations--development of feelings, growth, decay, and sometimes we introduce images or encourage stories. In general, we have discovered that about half of all children relate music to story, and half write absolute music that is not connected to any story or text (non-programmatic). This is very important to respect and not so easy to discern initially.

There is one form which I've found to be liberating and encouraging for the child who cannot at first get past the "blank page," and that is Theme and Variations. We find that children intuitively understand this particular form and relate to it profoundly. They seem able to take a melody or rhythm and just "go to town" on it. I seldom encounter a kid who just plays the theme in eighth-notes, say, or merely changes articulation: they change the actual sentiment of the Tema, and that is rich, very rich indeed!

7) And lastly - for now, because I'm sure I'll think of other things in a few minutes, let me specify how we feel about "borrowing," or using bits of pop or classical tunes they've heard. Well, we all, all of us professional composers borrow in our works, (Igor Stravinsky said "good composers borrow; great composers steal.") And so of course, it will show up in the kids--even to the extent they try to "cheat" by attempting to convince us that something they copied is their own creation. Actually, I've never had much trouble with this, since I tell them it's okay! Go ahead and borrow, but please give credit to the original by writing it above the staff. It's fun. But, then, after a couple of measures, go off on your own, please, because who we want to hear is you. You are more interesting to us than someone we can hear on the TV or radio!

And on this subject, sometimes the most satisfying young composer is the child who doesn't believe that he or she is interesting, who has personal issues, is rebellious, or hates to participate in a group. Getting the core feeling out of this child, whether angry or alienated, is an truly amazing experience for all--one that can be completely unpredictable. That is one of the great joys of the Very Young Composers, and a joy that will sustain instrumental music well into the future

Caracas, April 13

Another day of wonders and the unpredictable.

Today, Diana Arismendi, head of El Taller de Escritura Creativa, the Center for Creative Writing, and a prominent Venezuelan composer, returns from Puerto Rico to help us organize our efforts. I need her to feel that our program of starting kids composing at a very early age will help her own efforts to bring composers more into prominence in the El Sistema curriculum, and in general, to further the national creative spirit.

Last night, Dani had asked me a very searching question: "If you say that these children already have it in them to compose, then exactly what is it that you give them?" An excellent question, deserving of a serious answer. So I write out to her a little essay in the form of numbered points. The Tools of Creativty by Jon Deak, April 10, 2010.pdf. (Don't worry, it's in English!)

Things are happening! We managed to get the main percussion "Profe" here to demonstrate all his instruments for the Young Composers. I told him that what we mainly wanted was for the kids to "interview" the instruments by asking questions of them and even playing them themselves. He seemed a bit surprised, but quite willing, and we all had a lot of fun listening to each other improvise short solos on the bongos, congas, woodblocks, guiro, toms, and many more. Some of the most shy kids had the very most interesting ideas. I wonder if these bursts of rhythmic swagger will translate in their own works. By the way, the Professor, Ivan Hernandez, along with every percussionist I ever see, says to say hello to Chris Lamb of the Philharmonic, along with Diana Arismendi and Alfredo Rugeles, the conductor. He must have made some impression here!

Back upstairs to go over interval and chord sentiment, recognition, getting them to become excited by the qualities of melodies with tiny intervals, perfect intervals, minor sevenths (space, yearning, canyon, anger) and types of dissonances. They seem to respond strongly to dissonances. All kids do, but this group seems much more inclined.

only about half of the students reliably hear the difference between a minor and a diminished chord. Am I doing something wrong here? They sing and solfege so well. There's just no way to predict the path of learning here. Somehow this is comforting and even exciting. We play a bit more rhythmic games, and they have great ability, yet does this translate into musical creativity?

Splitting up into small groups, we are able to focus more on individuals. Part of my process when students are at this stage, and especially with a large group like this, is to document the process by xeroxing, photocopying their sketches.Then Richard, Pedro and I can go over the results afterward and ask more informed questions next time. But we were told yesterday, the xerox machines were closed!! Today, ¡No se puede hacer impresiones! The orchestra has an urgent need and has commandeered all the machines! Believe me, after so many decades of working with professional orchestras across continents, I know better than to tangle with a librarian!

Notation, notation! Where's that blackboard? Why are there so many obstacles involved in creativity, most notably the mind itself? Richard is completely tied down in his group by José Gregorio (age nine), who is acting out again. Maybe we should hire babysitter? Diana is wonderful, yet struggling a bit with such an energetic group of small kids--ordinarily she teaches on the University level. I am convinced Mailyn (12) is trying to please me--she's too self-conscious to listen to herself.

Perhaps we can't do this after all. Perhaps we're kidding ourselves. And yet, look at the masterful work Luis is bringing to life. And Oscar. And from Irawo, between his acting out, we get bursts of wild, wonderful, expressive sounds in clumps and bunches. He gets excited, focused, follows a marvelous line, and then suddenly runs off, misbehaves, gets into a fight. But look at the wonderful viola line Daniela is developing, slowly moving to weave a texture with the other instruments. We look over her shoulder, and she hides her work. Girls in the corner with cellphones. Out, out! ¡Afuera, apagarlos! I wonder if non-composing musicians realize how messy creativity can be.

Fortunately, order comes of this chaos. Much good work and progress has been made today. I only hope they don't lose their manuscripts or forget them tomorrow, because we have no copies. We were told they would never have time nor the type of home situations where composing at night could take place. Yet they clearly are doing work and making progress between classes. Some of them have written three or four pieces!

Exhaustion.

Richard and I spend hours going over this progress, discussing techniques, talking with Diana, Dani and Pedro (23), who is beginning to show leadership and dedication. Richard is battling sickness bravely. He has been absolutely charming to everyone with his expert abilities, brightness, and gentle humor. But alas, he may have to go directly to bed, and miss this concert we've all been looking forward to.

My head is spinning.

-- Jon Deak

Click here for Part Six

**************************************************************************************************************

Jon Deak, born in the sand dunes of Indiana of East European parents, is a Composer, Contrabassist, and Educational pioneer. Educated at Oberlin College, the Julliard School, the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (Rome) and the University of Illinois, he joined the New York Philharmonic and served as its Associate Principal Bassist for many years, while continuing his professional composing, and studying with Pierre Boulez and Leonard Bernstein. During this time he also introduced ground-breaking performance techniques for the Contrabass, and in his orchestral writing, working with major orchestras across the country.

From 1994 - 97 he served as Composer In Residence (sponsored by Meet the Composer) with the Colorado Symphony under Marin Alsop, which is where he initiated the public school program now called The Very Young Composers (VYC).

With support from the New York Philharmonic and others, the VYC has grown steadily, winning a national award for excellence in 2004. The program has been introduced in Shanghai, Tokyo, and now in Venezuela, besides serving hundreds of children in eleven New York area Public Schools and such places as New England and Eagle County, Colorado. The New York Philharmonic has premiered 42 works for children, fully orchestrated by the children themselves, mostly under the ages of 13, as well as hundreds of chamber works in the public schools and libraries.

Daniela Bedoni, Guztavo Dudamel, and Jon Deak

Daniela Bedoni, Richard Mannoia, and Jon Deak with children from El Sistema

The first piece, the hijacking piece, which strikes me as a sort of way out there, Joe McCarthy world view where art education is being infiltrated by communists, is just the sort of thing that could end up in the hands of a right wing opposed to funding for the arts, including the NEA, NPR, PBS, CPB, etc. It goes so far as to attack Maxine Greene, making her appear like the second coming of Alger Hiss:

Greene Grants of up to $10,000 are awarded to teachers who "go beyond the standardized and the ordinary"; artists "whose works embody fresh social visions"; and individuals "who radically challenge or alter the public's imagination about social policy issues." The 2008 grantees included the Education for Liberation Network--whose 2007 conference, entitled "Free Minds, Free People: A Conference on Education for Liberation," bore the following slogan on its program cover: "If education is not given to the people, they will have to take it."

'Nuff said, but still, worth a fast read.

Okay, moving right along. What this did remind me of, was an issue I have wanted to address since last fall, being the very odd disconnect between those interested in arts and social justice, and the field of arts education.

At the Grantmakers in the Arts preconference last fall in Brooklyn, among the day-long sessions was a track for arts education and a track for arts and social justice.

When the facilitator for the afternoon arts education session, Eric Zachary, Annenberg Institute for School Reform, Director of Community Organizing and Engagement/New York City, learned that there was a separate track for arts and social justice, he appeared puzzled and asked: isn't this social justice? My answer: indeed, welcome to the arts field.

Okay, just in case you think I don't get the issue of arts and social justice, I think I have a decent handle on it. People are interested in this because arts have always had a role in this area, giving voice to issues, serving as a means of binding together a community, etc. And, for many, making deeper connections to social issues and the arts field appears to be a very direct way to connect arts, an often challenged field when it comes to community relevance, directly to grass roots issues and those working on the ground.

But hey folks, kids in urban centers being denied the rights by law and as human beings to a well rounded education that includes the arts is clearly a social justice issue, particularly when you consider how this all breaks along socio-economic and racial lines.

So, perhaps, when people are looking to connect the arts more to social justice, they might just look in their very own backyard so to speak, arts education, and ask what they can do to help.

And the really bad news is that this bill appears to be moving full steam ahead.

I am a big supporter of CTE. in fact, I am a member of the New York City Department of Education's Chancellors Advisory Council for Career and Technical Education. And my growing knowledge of CTE makes this legislative proposal read that much more tin-eared, or shall I say tone-deaf?

There may be those who feel that students in a CTE school, (CTE is what was once know as vocational/technical) do not need the arts. I mean why would an automobile mechanic, graphic designer, construction worker need to have a well-rounded education that includes the arts????

Funny I should ask.

The CTE of today has embraced an education that is at its core high quality and progressive. While graduates of such programs often move directly on to a career, often in trades, rather than college, leading educators in CTE know that these students need a well-rounded education same as students in traditional, or what were once called "academic" high schools. There are many who see elements of CTE school design and structure as the missing piece in non-CTE high schools, including the internships/externships, deep connections with professionals, ongoing practical professional development, real world experience, and more.

The notion that CTE students don't need the arts is completely backwards to a 21st century career and technical education. And, it is oddly similar to the notion that students in low performing schools don't need the arts or that there isn't time. It might be interesting to take a look at how CTE school demographics compare to traditional high schools in California...

Centrally, there are two issues with this terrible piece of legislation:

1. Are the arts just for those who go on to college, a dangerous approach by any measure?

2. This change in high school graduation policy will weaken one of the few quantifiable measurements concerning the provision of arts education at the K-12 level: the high school graduation requirement.

As a small observation, I also find this change interesting, as it is quite the bucket of cold water on the notion of the creative economy. For all the talk about this economy, a big one in the State of California, how is that the very same state may wipe out arts education in CTE high schools?

The California Alliance of the Arts has posted an item on this, including a link to send an email in protest.

There are a few other policy matters I will bring to your attention in the next week or so, for in particular they illuminate some of the ways the arts and arts education field has yet to get its own act together.

Here's a clip of the section of the bill in question:

AB 2446, as amended, Furutani. Graduation requirements.

Existing law prohibits a pupil from receiving a diploma of

graduation from high school unless he or she completes specified

requirements, including, but not limited to, completing one course in

visual or performing arts or foreign language.

This bill , commencing with the 2011- 12 school

year and until July 1, 2016, would add completion of a course

in career technical education, as defined, as an alternative to the

requirement that a pupil complete a course in visual or performing

arts or foreign language.

Vote: majority. Appropriation: no. Fiscal committee: no.

State-mandated local program: no.

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS:

SECTION 1. (a) The Legislature hereby finds and declares the

following:

(1) The foundational principle of the Education Code is that all

pupils shall have access to equitable educational opportunities and

resources.

(2) The future of the state is dependent upon minimizing, if not

entirely alleviating, the inequities in our public schools so that

all pupils will have more equitable opportunities to learn skills

needed for entry into the workforce, to pursue postsecondary

educational goals, and to contribute to the social cohesion of the

state.

(3) Current law specifies the courses a pupil must complete to

graduate from high school. However, too many pupils are dropping out

of high school or graduating without the necessary foundation to

succeed in the workplace or in postsecondary education.

(b) It is the intent of the Legislature that:

(1) By specifying the types of coursework that pupils must

complete in order to graduate, pupils will have world class skills

and the workforce of the state will be competitive in the global

economy.

(2) Pupils will be prepared to meet the academic and technical

skills challenges of the high school curriculum and that they will

take advantage of the range of course options available to them.

(3) In order to increase the rigor of the coursework and to ensure

that pupils are prepared to meet the demands of the 21st century,

the courses required for high school graduation must be aligned with

the standards and frameworks that are adopted by the state board.

SEC. 2. Section 51225.3 of the Education Code is amended to read:

51225.3. (a) A pupil shall complete all of the following while in

grades 9 to 12, inclusive, in order to receive a diploma of

graduation from high school:

(1) At least the following numbers of courses in the subjects

specified, each course having a duration of one year, unless

otherwise specified:

(A) Three courses in English.

(B) Two courses in mathematics.

(C) Two courses in science, including biological and physical

sciences.

(D) Three courses in social studies, including United States

history and geography; world history, culture, and geography; a

one-semester course in American government and civics; and a

one-semester course in economics.

(E) One course in visual or performing arts, foreign language, or

, commencing with the 2011-12 school year, career

technical education.

(i) For the purposes of satisfying the requirement specified in

this subparagraph, a course in American Sign Language shall be deemed

a course in foreign language.

(ii) For purposes of this subparagraph, "a course in career

technical education" means a course in a district-operated career

technical education program that is aligned to the

career technical model curriculum standards and framework adopted by

the state board .

(iii) This subparagraph does not require a school or school

district that currently does not offer career technical education

courses to start new career technical education programs for purposes

of this section.

(F) Two courses in physical education, unless the pupil has been

exempted pursuant to the provisions of this code.

(2) Other coursework requirements adopted by the governing board

of the school district.

(b) The governing board, with the active involvement of parents,

administrators, teachers, and pupils, shall adopt alternative means

for pupils to complete the prescribed course of study that may

include practical demonstration of skills and competencies,

supervised work experience or other outside school experience, career

technical education classes offered in high schools, courses offered

by regional occupational centers or programs, interdisciplinary

study, independent study, and credit earned at a postsecondary

institution. Requirements for graduation and specified alternative

modes for completing the prescribed course of study shall be made

available to pupils, parents, and the public.

(c) Notwithstanding any other provision of law, a school district

shall exempt a pupil in foster care from all coursework and other

requirements adopted by the governing board of the district that are

in addition to the statewide coursework requirements specified in

this section if the pupil, while he or she is in grade 11 or 12,

transfers into the district from another school district or between

high schools within the district, unless the district makes a finding

that the pupil is reasonably able to complete the additional

requirements in time to graduate from high school while he or she

remains eligible for foster care benefits pursuant to state law. A

school district shall notify a pupil in foster care who is granted an

exemption pursuant to this subdivision, and, as appropriate, the

person holding the right to make educational decisions for the pupil,

if any of the requirements that are waived will affect the pupil's

ability to gain admission to a postsecondary educational institution

and shall provide information about transfer opportunities available

through the California Community Colleges.

(d) This section shall become inoperative on July 1, 2016, and, as

of January 1, 2017, is repealed, unless a later enacted statute,

that becomes operative on or before January 1, 2017, deletes or

extends the dates on which it becomes inoperative and is repealed.

Caracas,

April 12-13, 2010

This will be the start of "The Week That Was!" for us and this wonderful, colorful band of children. If I didn't know through years of composing symphonic music that creativity can indeed be given a boost in restricted, unknown and time-intensive circumstances, I would say this could not be done, even attempted.

But Richard Mannoia and I, together with Dani Bedoni of El Sistema, are determined to accomplish two major goals this week: First, to provide these children with warmth and empowerment, and a chance to realize their own creativity. Second, in taking their artistic efforts truly seriously, to give El Sistema and the wider musical world even the slightest and most fleeting glimpse of what children's art (and therefore great art) might sound like in the future.

Children, show us the way!

That said, no one can assume that the way will be easy. What I so love about this project, is the fact that El Sistema, with its spectacular successes and established results worldwide, has nonetheless not forgotten its experimental roots! From its very top: from Maestro José Antonio Abreu, from Gustavo Dudamel, to all its administrators, staff and students, I feel an abiding sense of support, interest, and above all patience.

Monday, the 12th of April. We arrive a bit late, and the children, mostly from the Montalban district, are even later. They must endure a long bus ride after their days at school, and even Dani's organizational genius cannot change the famous and unpredictable traffic jams of Caracas. As prepared as we are, we are constantly altering plans, adapting, experimenting.

Even more children are here today!

They are energetic, eager and somewhat disoriented as well. It appears that they have done quite a bit of work over the weekend, contrary to our expectations. With this many children, even splitting them up into smaller groups, we are forced to rely on their notational skills to some extent. That they have notational skills at this age is a blessing and a curse. (Well, okay, a bit of a "problem"): "literacy" has in many cases caused them to channel their ideas into pre-defined paths. Even our constant encouragement to graphically express their free ideas, to think of their instruments as magically empowered, does not always get through. We are getting lots of white-key pitches and quarter-note rhythms. As before, the way around this is to get them to sing, tap, hum, dance what they've written, and to take that as the urtext, not what they self-edit in their notation. But this takes time.

Both Dani and a young composer named Pedro Bernardez have already arrived at a deep understanding of this creative process, take delight in it, are able to work somewhat independently with the kids, and this is truly a godsend. Rosa Contreras, a violinist-composer, is also very helpful. Still, the process takes time. How could it not? Is there enough time? Will the arrival of Diana Arismendi, the head composer here, facilitate the process?

We need so much! It's called, well: infrastructure: we need scribes, a working xerox machine, more classrooms, keyboards, time to work on an individual basis, composer/teachers, professional level musicians, (especially a percussionist today!), a blackboard of some sort, firm rehearsal times, proofreaders, and Diana Arismendi!

One exercise I introduce to the general class is a form that I feel liberates, rather than limits kids: theme and variations. At least we've had success with this form in the past. We never demonstrate the Mozart Ah Vous drai-je, Maman , variations on Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star, but rather merely mention the idea of "keeping something and changing something, especially the feeling," which seems to give them real freedom, yet a little island from which to start, as some are intimidated by the blank page.

But whose theme? So, we decide to vote. I ask for four volunteers to submit a theme of their own, and immediately get fifteen! A theme by Luis Pichardo eventually wins the final round, with several other strong contenders. A team spirit, rather than merely competitive infighting seems to pervade. Would that adults could be so mature.

Nine students express a desire to form a theme-and-variations work. Will they follow through on this? Well, what matters more is that they feel this gives them a place from which to start.

The children do like to make fun of my grammatical errors, which slows things down, but Dani is always there to help. I laugh often, and tell them that the important thing is not my speech but their music. We even have them demonstrate the rhythm of their speech and physical movements.

A big job, but a good class today.

At night, we attend a rehearsal of the Simón Bolívar Orchestra, again conducted by Gustavo, who leads them through the Cantata Criolla, written by the Venezuelan composer Antonio Estevez in 1957. Again, we are amazed by the ensemble, technical precision and especially the rhythmic surety. I look at the score and realize how severely most North American Orchestras would be challenged by it: long passages written in 15/16 - 2/8 - 17/16 - 3/8 time, and executed with unanimity and a convincing "groove" by entire sections. Can you imagine this with most orchestras?

And still, after the rehearsal, Gustavo again urges us in giving importance to the Young Composers' project, which we are now beginning to refer to as "JoCoVen," a local-type of acronym for "Jóvenes Compositores Venezolanos."

Just another day of marvels and hard work.

--Jon Deak

Click here for Part Five

***************************************************************************************************************

Jon Deak, born in the sand dunes of Indiana of East European parents, is a Composer, Contrabassist, and Educational pioneer. Educated at Oberlin College, the Julliard School, the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (Rome) and the University of Illinois, he joined the New York Philharmonic and served as its Associate Principal Bassist for many years, while continuing his professional composing, and studying with Pierre Boulez and Leonard Bernstein. During this time he also introduced ground-breaking performance techniques for the Contrabass, and in his orchestral writing, working with major orchestras across the country.

From 1994 - 97 he served as Composer In Residence (sponsored by Meet the Composer) with the Colorado Symphony under Marin Alsop, which is where he initiated the public school program now called The Very Young Composers (VYC).

With support from the New York Philharmonic and others, the VYC has grown steadily, winning a national award for excellence in 2004. The program has been introduced in Shanghai, Tokyo, and now in Venezuela, besides serving hundreds of children in eleven New York area Public Schools and such places as New England and Eagle County, Colorado. The New York Philharmonic has premiered 42 works for children, fully orchestrated by the children themselves, mostly under the ages of 13, as well as hundreds of chamber works in the public schools and libraries.

Daniela Bedoni, Guztavo Dudamel, and Jon Deak

Daniela Bedoni, Richard Mannoia, and Jon Deak with children from El Sistema

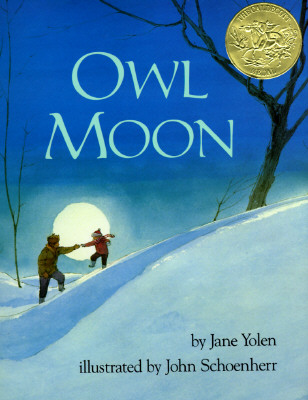

For my money, the Caldecott Award is a real measure of quality. Of course there are others like Newbery, Geisel, etc. And, with a five-year old daughter, I spend time a lot of time looking for such books. On one side of the spectrum you find the fast food nation of books for children--the Nickelodeon, Barbie-sort of books. JHave you ever tried to read the Scooby Doo books for children, with their often cheap, machine-like illustrations and inane stories, which oddly enough, my daughter happens to prefer. One should never underestimate the power of marketing! I digress...

For my money, the Caldecott Award is a real measure of quality. Of course there are others like Newbery, Geisel, etc. And, with a five-year old daughter, I spend time a lot of time looking for such books. On one side of the spectrum you find the fast food nation of books for children--the Nickelodeon, Barbie-sort of books. JHave you ever tried to read the Scooby Doo books for children, with their often cheap, machine-like illustrations and inane stories, which oddly enough, my daughter happens to prefer. One should never underestimate the power of marketing! I digress...The other side of the spectrum is occupied by Caldecott winners.

I first came across Owl Moon in an integrated arts education curriculum that Rob Horowitz was writing for a Baltimore Symphony school partnership program.

Here, Owl Moon became deconstructed and reconstructed. It was a lesson that I used and varied quite a bit when I led professional development sessions for teachers and artists. Owl Moon was the centerpiece.

A beautiful story, that just comes alive through Schoenherr's illustrations. The simple walk through the winter night becomes magical through the Yolen-Schoenherr collaboration.

What we used to do with it, it being Owl Moon, was basically use it as the anchor for an integrated arts lesson at the first grade level. To begin with, the teacher would read the story aloud and show the pictures, you know, classic-style.

Then, using instruments made by the class together with a teaching artists from the BSO, the class would construct a soundtrack to Owl Moon.

Owl Moon would then be read out loud by the class, along with the soundtrack.

Then, the classroom teacher would choreograph a dance to Owl Moon.

The story would be told with the dance to the soundtrack, sans text.

Then, the children would create their own illustrations with the art teacher.

Owl Moon would then be told by a pairing of the illustrations with the music.

Finally, it would all be combined, text, original illustrations and children's illustrations side-by-side, together with the dance.

A nice little lesson plan, making the most of existing skills and building new ones for the children, teachers, and teaching artist. All revolving around that most beautiful of books, Owl Moon.

It was an in-depth lesson that gave great dimension to the book through the integration of literacy, dance, music, instrument making, and visual art.

There are just so many variations of this particular lesson, that all in their own way, make the book come alive for the class. Every time I've looked at Owl Moon since those days, I think of that lesson.

So, to the great artist who illustrated Owl Moon, and so much more, I say thank you and Rest in Peace.

Caracas, April 9-10, 2010

The excitement builds. Also the nerves. Have you ever noticed how, when you travel to a completely new environment, all emotions are magnified? The joys are expansive, the fears are bottomless, each event rings clear, vibrates with color. I feel I should go to bed wearing dark sunglasses!

And yet, there is a penetration to truth and genuine learning, if only one can sort things out. After all, we're not talking here about hallucinations or drugs: These are real experiences.

So begins our second day of classes, Richard Mannoia and myself. Our quest, perhaps quixotic, is to bring a program of children's creativity, (our Very Young Composers) to the vast and vastly successful El Sistema. As Maestro Jose Antonio Abreu's program spreads throughout the world and revolutionizes music education, children and societies, so we wish to present ourselves as composers' advocates, and release the miraculous creativity that is in children everywhere. Patience. Patience and persistence. This is going to take awhile. It is thanks to the New York Philharmonic, the Halbreich Foundation, El Sistema's invitation, and countless supporters and friends that we are even here.

Waking up to a new day, preparing for class, I am contacted by Dani Bedoni. Would I like to come and observe Gustavo Dudamel rehearse the Simon Bolivar "B" Orchestra in the Mahler 7th Symphony? Of course I would! She has arranged for permission, but we must leave immediately. (She had mentioned this to me last night, but nothing was certain.)

Taking a last gulp of the marvelous Venezuelan coffee, I rush to the lobby, where we drive to the Teresa Carreño Theater. The theater had been commandeered by the Chavez government for its sole use until recently, when the immense popularity of El Sistema's music program was recognized, and is now open to them. Onstage, Gustavo is rehearsing. Hearing the first measures of the vast first movement, my eyes immediately widen, my jaw threatens to drop, and I am in a different world. Now, I had heard, very briefly, this orchestra in rehearsal in Carnegie Hall, and had worked with the Orquesta Juvenil de las Americas. The prowess of these young people was not unknown to me. And yet somehow hearing them this morning, not only the energy, brilliance and accuracy of ensemble and intonation were streaming out like fireworks, but it was clear that Gustavo was shaping the work in such a penetrating, passionate way, that you could tell an important musical statement was about to break forth. The control, the rhythmic drive, the ensemble, especially in the strings, was palpable.

Marvelous horn solos, viola, flute. . . and on and on.

Rather dazed, I wander out to stage-left during intermission, and talk to the violas and bass players. Gustavo is in the center of a presentation: He is receiving the Legion d'Honneur from the French government for his service to music. I'm feeling like a tiny flea on the wall, delighted and all, but how can I hope to be of any help to all this? I'm just glad to be here. And yet - Gustavo, true to his form, catches sight of me, interrupts his photo-op, rushes over to give us a hug (there are lots of hugs in Venezuela!) and speaks excitedly to me and Dani about the composing program.

Energized and elated by the performance, and yet feeling a weight of responsibility like, yow, we go to the afternoon's three-hour class. I hope these people don't expect their children in seven class days to come up with great masterpieces! I mean, I know all kids are miraculous, (look who you're talking to!) but this work does take time, after all.

So the second class begins quite favorably. There are now 24 children, three new faces, and more are due for the third class. We begin with greetings and a recap of the Ear Fantasy chord and interval description game. Then, who did the assignment for bass and clarinet? Fine, almost all the kids did! And good stuff, too. Even the shy kids were willing to share.

Even at this introductory stage, it comes clear that, since these kids are well-versed in solfege and reading music, that they are limiting themselves to what they can notate. In other words, they are writing from the head, not from the heart. I have mentioned this over and over already, had Dani and Pedro repeat it, but it's not an easy thing to put aside. Again, a few of them have copied out music that they are playing in their ensembles. We talk gently about this, yet firmly.

For me, the best part of the day is when Richard, again with his superb class technique and experience, helps us devise a rhythmic creative exercise as a break-out into small groups. We talk about dance rhythms, several kids even demonstrate a Joropo, Salsa, and other dances. Groups of five or six kids take about 15 minutes and devise their own take on rhythms to perform for the larger group. Each one has a special part, a contrubution. We are using hands, bodies, voices and small percussion instruments. the results are both fun and impressive. Will this translate into their own works? We will see. We cannot force, otherwise, it's them pleasing us, and therefore not their own music at all.

Finally, Pedro and Rosa demonstrate the violin and the Venezuelan cuatro, a small guitar with four strings. I would rather, as many of you know already, have had a truly interactive demo, since many of the kids play violin, but they did ask many questions and seemed involved. We of course encourage them to compose while using their instruments, and yet, to imagine that their instruments are magic and can do wondrous things. (That's one reason we like to use professionals or advanced performers for the actual concert, though we want them to play along, too.)

After class, Dani and Richard document the session, detailing each child's progress. FESNOJIV (Fundacion del Estado para el Sistema Nacional de las Orquestas Juveniles e Infantiles de Venezuela), does make it clear that it values learning objectives for each child. As Richard says, it is not enough just to keep kids busy, but is always looking for justifiable, rich learning experiences. This is impressive, and certainly one of the reasons for El Sistema's strength.

Saturday, April 10th

Regular after-school classes are not held on Saturday, and yet many of the children in the Montalban district attend morning classes in the local school.

Already reeling from the powerful experiences of the first two days of classes and the Simon Bolivar Orchestra rehearsal, I still was not totally prepared to witness El Sistema in its local habitats. True, we were treated mostly to prepared performances, but the process is becoming clearer and clearer (while still in the miraculous realm!)

We first observed the Orquesta Infantil "Caracas." This is an orchestra of 12-14 year-olds. Can you believe they were playing the Tchaikovsky 3rd symphony Finale, with all its complex articulations and technical writing--and with superb style? The accuracy of intonation is most evident in the strings, and yet Richard noticed that the seven or eight flutes were right on target pitch-wise. An amazing achievement at that age. One of the reasons is that they rehearse as an orchestra five, sometimes six days a week. This is unheard of with in America. I told these children we feel the whole world would be proud of them, and I meant it.

Next, we heard a chorus of some one hundred children, even younger. They were singing Venezuelan folk songs, "Se Enojo la Luna," "El Arco Iris," and others. Of course I love to hear them honoring their own culture. And even more, the clarity of the voices, again the intonation and rhythmic unity, the heartfelt expression--how can you listen to this and not be reduced to tears? This is getting embarrassing!

As if this weren't enough, we sat in on a string sectional rehearsal. Over and over, the bowings and articulations were repeated: four sixteenths up-bow, triplet scales down-up-up, again, again and again. And there they were: Mailyn, Oscar and Luis, my composition students, playing in the viola, cello and violin sections! Pride all around, and a lot of it emanating from Richard and me.

Next, a brass sectional working on Elgar's Pomp & Circumstance. Very young kids. Excellent technique, always involved, asking questions, the teacher gentle, yet in control.

Next, to a room of pre-schoolers. I would have taken their ages as 2 or 3, they were SO small, but when I asked them their ages, they held up 4 or 5 fingers. A teacher at the piano, smiling, clearly enjoying herself. Dalcroze influenced, most likely. El Sistema does nothing if not learn from the best techniques in the world, then adapting them to their own local genius.

And finally, a recorder class, or Flauto Dulce. Elementary school age kids. Here we could begin to see how the basics and the solfege are imparted. They sing, then play. Play, then sing. Yes, they used a theme from the movie Titanic, but we also enjoyed Niño Lindo, un aguinaldo popular Venezolano.

We could see all around us, the neighborhoods where these children live. We were in a children's safe haven amongst all of it. The parents were waiting outside the chain-link fence to pick up their children. "Not safe." Dani said, simply.

I shake my head in confusion and disbelief, and yet in deep perception of what is going on. At night, we party hard. We have a drink at Dani's family house, meet some wonderful new friends, and best of all, Dani & Gonzalo's three wonderful children whom I'd met back in New York. Finally, wild luau party down the block. Wow, were we wasted. On Sunday, Richard and I went off and took a Teleferico Tram up El Avila, which was a cultural marvel all in itself: A teeming local tourist trap. What a. . . what a. . . country this is!! I can't open my eyes wide enough to take it all in.

(Heh. Me, the big world traveler and wilderness mountaineer. Guess i haven't seen it all, yet.)

--Jon Deak

Click here for Part Four

**********************************************************************************************************

Jon Deak, born in the sand dunes of Indiana of East European parents, is a Composer, Contrabassist, and Educational pioneer. Educated at Oberlin College, the Julliard School, the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (Rome) and the University of Illinois, he joined the New York Philharmonic and served as its Associate Principal Bassist for many years, while continuing his professional composing, and studying with Pierre Boulez and Leonard Bernstein. During this time he also introduced ground-breaking performance techniques for the Contrabass, and in his orchestral writing, working with major orchestras across the country.

From 1994 - 97 he served as Composer In Residence (sponsored by Meet the Composer) with the Colorado Symphony under Marin Alsop, which is where he initiated the public school program now called The Very Young Composers (VYC).

With support from the New York Philharmonic and others, the VYC has grown steadily, winning a national award for excellence in 2004. The program has been introduced in Shanghai, Tokyo, and now in Venezuela, besides serving hundreds of children in eleven New York area Public Schools and such places as New England and Eagle County, Colorado. The New York Philharmonic has premiered 42 works for children, fully orchestrated by the children themselves, mostly under the ages of 13, as well as hundreds of chamber works in the public schools and libraries.

Daniela Bedoni, Guztavo Dudamel, and Jon Deak

Daniela Bedoni, Richard Mannoia, and Jon Deak with children from El Sistema

Caracas, April 8, 2010

We're here!

It seems impossible to describe all the events and feelings of just the first twenty-four hours of our trip to Venezuela, to experience and interact with El Sistema. I've been so long in awe of this program which is revolutionizing this country and the musical world in the best possible way--and now here we are, in its native habitat, so to speak, ready to dig in, learn, express and interact.

The fact that we are daring to interact with it in some small way has made me extremely nervous, as I've mentioned in my initial post. My trusty teaching artist, Richard Mannoia and I have prepared for this for many months, yet still there's no way to really know what we're in for.

My mood and spirit were immediately lifted by a four-year-old Venezuelan boy named Ikenna, whom I met in the flight lounge while waiting to change planes in Bogota'. I'd had on my lap the long Spanish dissertation on my composer contact, Diana Arismendi. As Ikenna and i struck up a conversation, I pulled out my little packet of colored pencils (yes, folks, I admit to carrying them around in my backpack), and he began to go to town on the cover page of my dissertation. His mother was horrified. I quickly assured her that, not only did he draw a portrait of his big sister, which told me of his feelings about her, but he "invented" an animal! A sea-going Hippopotamus with legs long enough to reach the bottom, so he could walk through the water. Needless to say, I gave him the pack of pencils, and hope he creates his portfolio. Maybe we'll hear about "Ikenna The Artist" someday. Who knows?

I tell you, every day it seems we get confirmation that we are in the right kind of work.

On arrival in Caracas, Richard and I were met and escorted by Dani Bedoni and staff from El Sistema. The ride from the airport alone told the story: Vast shanty-towns, Barrios, perched on the steep hills outside town, swarming for miles--contrasted with the glittering towers of Caracas's financial and political center. Political and revolutionary posters and graffiti everywhere.

But no time to reflect, tour or get acclimated. (Richard and I both contracted colds from the flight.) Right the next day our Very Young Composers classes begin. However, the unexpected is a part of life here, along with the efficient and the ambitious: I am told that instead of six to eight kids, we will be working with upwards of 30. And of varied ages from 8 to 14. I'm a bit thrown by this. (Dani says: El Sistema like to think big!) Also, Diana Arismendi, who is to be our composer/organizer, will not be here until next Tuesday, as she is giving a seminar in Puerto Rico.

However, we have Pedro and Rosa, two grad student composers to help us, and as always, Dani is there to organize, smooth and prepare. And the kids are bright-eyed, eager, and full of energy. Despite considerable study of Spanish in recent months, I find it hard to understand them when they speak quickly, and Dani and Pedro are very helpful in that regard. (I speak Italian, but it doesn't seem to help all that much.)

Richard and I had sent out a video on YouTube for the students to prepare for us, and part of that was an assignment: "Tell us about a dream you have, whether a sleeping one or a conscious one." Most of them chose the latter, and when they got up, we heard repeatedly: "My dream is of me standing in front of a big audience and playing the Violin. . . I dream of being a great composer. . . I dream of flying up with the birds, above the mountains. . ."

Another part of the assignment was to write something: "four sounds," or a melody, for clarinet and/or bass. Richard and I both demonstrated our instruments and I let many of them play some notes on my bass. The melodies or sounds that the children wrote were, as I expected, fascinating and original. However, it seemed as if many of them either hadn't written anything, or were shy to give us what they had. I suspected the latter. Also, several of them submitted pieces they were playing in orchestra, instead of their own.

Then some rhythmic games were played, passing around from student to student, and right away here I could see how brilliant Richard is at his work with kids. I followed with my "Ear Fantasy" game, in which chords (major, minor, diminished, etc) are played and identified by emotion rather than by name.

Fun! They seemed to be getting over some shyness.

All of them have quickly become favorite personalities of ours. Love 'em! Right away, one named Jose' Gregorio, a very small nine-yr -old, brimming with energy, got up on a chair and played my bass - the bass part to the Hallelujah Chorus! He did the entire thing by memory. His hands were so small that he couldn't stretch a whole-step, and it came out in D minor, if you can imagine that.

We gave them mostly individual assignments for the next day, to work on their music, and the three-hour class came to an end. It was clear that we would have to separate the older from the younger kids in some way, at least in breakout sessions, and also that the pitch and rhythms that I know must be in their bodies must be somehow encouraged to come out. (Just look at the way they move and swagger!) They are used to being disciplined and told what to do.

How to free up the creative consciousness without losing the incredible benefits of the discipline?

Of the many core values of El Sistema, is the primary goal of saving the child. So many of them are at-risk, impoverished children, from broken homes, and this program cares for them and gives them a supportive environment. I am told that abuse of children is not a major issue here. Perhaps this is why I don't right away see a lot of anger, as we often see in some of our schools. But it's too early to tell much, really.

We do know that once a child is "saved," that an amazing and successful effort is made to achieve musical excellence.

Gustavo Dudamel is in town, and tomorrow morning, we get to go and hear his rehearsal of the Mahler 7th in the Teresa Carreño Theater, which I remember playing in, years ago, with the New York Philharmonic. This will be the first time performing this piece both for him and for the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra ( the "B" orchestra--the younger of the two.)

This I gotta hear!

--Jon Deak

Click here for Part Three

**************************************************************************************************************

Jon Deak, born in the sand dunes of Indiana of East European parents, is a Composer, Contrabassist, and Educational pioneer. Educated at Oberlin College, the Julliard School, the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia (Rome) and the University of Illinois, he joined the New York Philharmonic and served as its Associate Principal Bassist for many years, while continuing his professional composing, and studying with Pierre Boulez and Leonard Bernstein. During this time he also introduced ground-breaking performance techniques for the Contrabass, and in his orchestral writing, working with major orchestras across the country.

From 1994 - 97 he served as Composer In Residence (sponsored by Meet the Composer) with the Colorado Symphony under Marin Alsop, which is where he initiated the public school program now called The Very Young Composers (VYC).

With support from the New York Philharmonic and others, the VYC has grown steadily, winning a national award for excellence in 2004. The program has been introduced in Shanghai, Tokyo, and now in Venezuela, besides serving hundreds of children in eleven New York area Public Schools and such places as New England and Eagle County, Colorado. The New York Philharmonic has premiered 42 works for children, fully orchestrated by the children themselves, mostly under the ages of 13, as well as hundreds of chamber works in the public schools and libraries.

Daniela Bedoni, Guztavo Dudamel, and Jon Deak

Daniela Bedoni, Richard Mannoia, and Jon Deak with children from El Sistema

When school systems and state departments of education fail to establish instructional standards that include required levels of minimum instruction and/or fail to enforce such required minimums, what you get is a system completely out of whack.

Here's a link to the article: Rich School; Poor School, by Kate Pastor.

Here's the invitation to PS321's upcoming benefit. A terrific school, a terrific principal, a terrific program, terrific teachers, and a terrific parent organization. If only every school could do this."We don't have silent auctions and all those things. That's just not our population," González says.

It's a very different story at the William Penn School (P.S.321), located in pricey Park Slope, Brooklyn. Its Parent-Teacher Association brings in approximately $500,000 in annual revenue, according to PTA Co-President Jill Mont. Its biggest fundraisers, a spring dance and an auction, collected between $75,000 and $80,000 apiece last year, and an annual appeal rakes in about $100,000--combining for about 60 times M.S.223's annual PA budget.

Let me start from the beginning. As most of you know, last Friday at the Arts Education Partnership (AEP) Forum held in DC, both Arne Duncan, Secretary of Education and Rocco Landesman, Chairman, National Endowment for the Arts gave speeches on arts education.

If you didn't know, humm, perhaps you've been traveling abroad?

I would like to focus this entry on Duncan. Although I will say that most people are pretty happy with Landesman's speech. For a first speech on this topic, very likely a first in his career, it was a very positive, sunny, and community-oriented speech. While I have to take issue with the speech failing to recognize the long-term challenges to providing equitable access to arts education, something that is foremost on the minds of anyone connected with urban school districts, I think it's fair to give Landesman a high grade for this, his first speech.

Moving right along to Secretary Duncan, I think he gets very high grades for just showing up. That's right: just showing up. And by showing up, I mean speaking to the issue of arts education across numerous public appearances, making his most senior staff accessible, and saying much of the right things, in general. This is new territory for the USDOE.

Let me be perfectly clear about this. Few secretaries of education over the past 30 years have even acknowledged the arts. Go back and look for similar speeches from Spellings, Paige, Riley, Alexander, Bennett, etc. You are going to be hard pressed to find much of anything.

On that basis, there's a lot to be happy about.

However, unlike Landesman, this was not Duncan's first time at the arts education speech rodeo. It's getting to the point where people are hungry to hear something more. So, I have taken the liberty of adding a couple of paragraph to Duncan's speech. The paragraphs fall under the category of what might have been. The section added by me, is in bold and italics.

If I have the time, I may just try and do a little mash-up of Duncan and Landesman's speeches, to see how it would swing in one speech combined.

http://www2.ed.gov/news/speeches/2010/04/04092010.html

The Well-Rounded Curriculum

Secretary Arne Duncan's Remarks at the Arts Education Partnership National Forum

| FOR RELEASE: April 9, 2010 |

If there is a message that I hope you will take away from today's conference it is this: The arts can no longer be treated as a frill. As First Lady Michelle Obama has said, "the arts are not just a nice thing to have or do if there is free time or if one can afford it... Paintings and poetry, music and design... they all define who we are as a people."

All of you know the history all too well. For decades, arts education has been treated as though it was the novice teacher at school, the last hired and first fired when times get tough. But President Obama, the First Lady, and I reject the notion that the arts, history, foreign languages, geography, and civics are ornamental offerings that can or should be cut from schools during a fiscal crunch. The truth is that, in the information age, a well-rounded curriculum is not a luxury but a necessity.

That is why I am excited to announce that we are instituting a new policy to help make my remarks today a reality across the United States. For too long the arts have been overwhelmed by other interests and issues, and we will no longer allow that to happen through any of our policies and programs at the USDOE.

Starting today, we will institute a policy that requires all funded programs at the USDOE to include a provision requiring that applicants and grantees certify that their programs will not negatively impact arts education. And what is more, we will ask them to indicate how programs in other areas will help to support arts education in each applicable school community.

For years we have required that certain programs are supplemental and do not supplant. Based on that precedent, we believe that this intervention can help to ensure that the curriculum will be expanded, not narrowed, and that arts education as part of a well rounded education will be advanced and expanded rather than diminished.

This provision will be incorporated into ESEA and across all programs going forward. I only wish that this had been done in time to be incorporated into the Race to the Top and i3 guidelines

I am not going to sugarcoat the tough choices that many districts are facing this year. State and local school budgets are absolutely strained across the country. Many of you are fighting lonely battles to preserve funding for arts education. There is no getting around that fact--and I applaud your commitment to fully educating America's children by engaging them in the arts.

At the same time, in challenge lies opportunity. As Rahm Emanuel has said, "you never want a serious crisis to go to waste." Now-- as we move forward with reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act--is the time to rethink and strengthen arts education.

And I ask you to help build the national case for the importance of a well-rounded curriculum--not just in the arts but in the humanities writ large.

The question of what constitutes an educated person has been taken up by the great thinkers in every society. Yet few of those leading lights have concluded that a well-educated person need only learn math, science, and read in their native tongue. As James Leach, the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities recently put it, a society that fails to study history, refuses to learn from literature, and denies the lessons of philosophy "imprisons [its] thoughts in the here and now." A well-educated student, in other words, is exposed to a well-rounded curriculum. It is the making of connections, conveyed by a rich core curriculum, which ultimately empowers students to develop convictions and reach their full academic and social potential.

The study of history and civics helps provide that sense of time beyond the here and now. The study of geography and culture helps build a sense of space and place. And the study of drama, dance, music, and visual arts helps students explore realities and ideas that cannot be summarized simply or even expressed in words or numbers.

That complexity forces students to grapple with and resolve questions that will not have a single, correct, fill-in-the-bubble solution.

In America, education has long served a special role: It has been the great equalizer. From Thomas Jefferson on, America's leaders have recognized that public education and the study of the liberal arts were essential to creating an informed citizenry that could vote and participate in civil society. In 1784, years before the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia and only weeks after the war with the British had ended, George Washington sat down to write a letter to a bookseller.

But Washington did not recount the recent triumph over the British. He asked for books instead, because, he wrote, "to encourage literature and the arts is a duty which every good citizen owes to his country."

In America, we do not reserve arts education for privileged students or the elite. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds, students who are English language learners, and students with disabilities often do not get the enrichment experiences of affluent students anywhere except at school. President Obama recalls that when he was a child "you always had an art teacher and a music teacher. Even in the poorest school districts, everyone had access to music and other arts."

Today, sadly, that is no longer the case. And that is one reason why I believe education is the civil rights issue of our generation--and why arts education remains so critical to leveling the playing field of opportunity. Robert Maynard Hutchins, the former president of the University of Chicago, put it well when he said that "the best education for the best is the best education for all."

I learned that lesson firsthand from my father, who was a psychology professor at the University of Chicago and a banjo player. He cared deeply about promoting student growth.

But he was even more committed to a dual mission for teachers--to not just educate students but to help prepare them for a lifetime of learning. You might say he was an amateur arts educator of sorts because he worked for many years as the faculty representative for the university's annual folk music festival.

Attending the folk festival every year growing up, my brother, sister, and I listened to the blues and bluegrass, African drummers and mariachi music, Chilean, Russian, and Ukrainian bands, Celtic music and gospel. We were exposed not just to music from across the globe, but, through music, the vastness and extraordinary diversity of the world itself.

I must confess that my father--at least in my case--failed to pass on his musical talents. Even so, I did flail away for several years on the drums in the middle school band. I learned some good lessons in the process--despite my forgettable performance.

The fact is that most students who take the arts are not going to be professional musicians, painters, dancers, or actors. Yet every student who plays in a band, acts in a play, dances in a company, or sings in the chorus can benefit from the experience in amazing ways.

Through the arts, students can learn teamwork and practice collaborative learning with their peers. They develop skills and judgment they didn't know they had--whether it is drumming in time or acquiring the knowledge to differentiate between Pavarotti and the tenor in the choir loft at the Sunday service.

No matter what the color of our skin or beliefs, "all of us can draw lessons from the works of history" says President Obama. "All of us can be moved by a symphony, all of us can be moved by a soprano's voice or a film's score." Art, that is, has a universal appeal because it speaks, as the President points out, to a shared yearning "for truth and for beauty, for connection and the simple pleasure of a good story."

Now, I spent much of last year on a Listening and Learning Tour that took me to more than 35 states. And I heard quite a few stories. I spoke with thousands of students, parents, and teachers.

And almost everywhere I went, I heard people express concern that the curriculum has narrowed, especially in schools that serve disproportionate numbers of disadvantaged students.

There is no doubt that math, reading, writing, and science are vital core components of a good education in today's global economy. But so is the study of history, foreign languages, civics, and the arts. And it is precisely because a broad and deep grounding in the arts and humanities is so vital that we must be perpetually vigilant that public schools, from pre-K through twelfth grade, do not narrow the curriculum.

The case for a well-rounded curriculum begins with a disappointing reality: Many schools today are falling far short of providing an engaging, content-rich curriculum. Instead, students are often saddled with boring textbooks, dummied-down to the lowest common denominator. It is no wonder that much of today's curriculum fails to spark student curiosity or stimulate a love of learning. As Ernest Boyer pointed out years ago, "Many kids drop out of school because no one ever noticed that they dropped in."

Yet we know from research that access to a challenging high school curriculum has a greater impact on whether a student will earn a four-year college degree than his or her high school test scores, class rank, or grades. And we know that low-income students are less likely to have access to these accelerated learning opportunities and college-level coursework than their peers.

One impact of the content-lite curriculum is that many Americans are appallingly ignorant of our nation's origins.

You will perhaps not be surprised to hear that a recent public opinion survey by the American Revolution Center found that more than 80 percent of Americans know Michael Jackson sang "Beat It" and "Billie Jean." By contrast, a majority of Americans believe the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, or the War of 1812 occurred before the Declaration of Independence.

Less than half of Americans today know that Valley Forge, the iconic site of George Washington's winter encampment with the Continental Army, is in Pennsylvania.

In the coming debate over ESEA reauthorization, I believe that arts education can help build the case for the importance of a well-rounded, content-rich curriculum in at least three ways.