Dewey 21C: February 2011 Archives

Art, gym, music and library programs would be particularly hard hit, losing 15% of their teachers.

Of course, this would be a hard pill to swallow, even more so considering the public pledge by the mayor and NYCDOE to ensure that the arts do not receive disproportionate cuts.

You can read more about this here: Ed Department Layoff List Cuts Some Schools' Faculty By Half; Union Calls Projections Fear-Mongering, Rachel Monahan, February 28th, New York Daily News

As this trend continues to evolve and grow, the spiritual qualities of America which was once, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, the "last best hope of mankind" will have been extinguished, while along with the intellectual and cultural environment, the physical environment will continue to decline. In order to see the consequences of this "educational reform" movement let's examine what a large proportion of our young learners are not being adequately taught as "test prep" increasingly crowds out the opportunity for giving them a comprehensive and sound education.

Tweet

Fair enough.

Tweet That being said, still, I was quite struck by the fact that the negotiations between Detroit Symphony management and the musicians had as a sticking point the issue of making work in the community, including schools, a more formal part of what defines an official service.

Here's an excerpt from the Detroit Symphony musicians website:

There are many misconceptions out there about education and community outreach as it relates to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. We, the musicians, have always done community outreach and education in many forms, both individually and with the DSO. Since the current management team has been here, we have done less and less. That is not our choice. We are not in any way opposed to community outreach.

If you have been following our own self-produced concerts, you have seen that we have been out in the community since September. Our thirteen concerts have been performed to large audiences in churches and schools throughout the Detroit metro area. As performers, we have been within a few feet of our audience and it has been as thrilling for us as it has been for them. Also we have talked with many, many supporters of classical music. We have been actively engaged with teachers, students and the community members about what they want from the DSO. And we believe that instead of imposing our own ideas or executives' ideas about what should take place, our neighbors and supporters across the region know best about their needs. We respect their desires and urge the executives at the DSO to join us in providing real community outreach by making the full orchestra available as a vehicle for reaching and teaching a wider audience as well as the next generation of students becoming world-class musicians.

We'd like to extend an invitation to DSO management, concerned board members, and any other donors to our concert at Groves High School on February 16th at 7 pm. This concert is the culmination of just one of our education and community outreach efforts made by the musicians of the DSO. This event promises to be a most inspiring experience for performers and audience alike. Please join us as we present one vision of a highly effective, future DSO Education and Community Outreach program.

So, here's an orchestra on the brink, in a city on the brink. And the question of whether or not a service could be a performance in the community/schools, and who determines the validity of the service, is something being argued about.

And at the very same time we have NEA Chair Rocco Landesman encouraging the arts field to do more education as a matter of survival, while Kennedy Center President, Michael Kaiser, tells the field that our problems are due to a lack of artistic vision, courage, and quality.

Okay, as in most things, there a bit that's right and a bit that's wrong in all of this.

But, you've gotta admit, it's quite the whiplash.

The issues with the Detroit Symphony led me to recall a my work as an arts education consultant in the mid-90s. We had among our client list a sizable number of symphony orchestras from the Big Five to many smaller orchestras.

My story focuses on one in particular, for the sake of a productive blog entry, let's call this orchestra, Orchestra Baby Boomer (OBB) (I would have chosen Orchestra X, but there is such an entity, I believe, based in Texas).

I had worked with OBB to develop a new comprehensive arts education program, including in-depth partnerships with a group of local public schools, a sequential and substantial curriculum intended to dovetail with existing curricula in other subjects, a wide range of resources provided to all classrooms, visits from the music director and other artistic leaders, concerts at OBB's concert venue, concerts by the full OBB at the school, professional development for teachers, a sizable assessment program, and classroom residencies by OBB artists, all of whom were receiving training by us to help them integrate with the program goals/structure, while helping to advance their overall skills as teaching artists.

In many ways, the program was a sort of Rolls Royce, and it was particularly noteworthy for the fact that all of the artistic leadership was participating directly. None of the let's reserve the education work for the assistant conductor sort of stuff.

Now, as a bit of context setting, I would like to point out that I knew a fair number of the New York Philharmonic musicians who performed for the venerated Young People's Concerts with Leonard Bernstein.

While many people view those programs as a sort of golden age for arts education and orchestras--televised orchestra education programs on commercial television, led by a dynamic music director with a gift for commitment and gift for communicating to children and youth--t would be fair to say that the musicians I knew from the New York Phil viewed children's concerts as something second rate. There was a sort of natural disdain unmistakable when they said: "We have to play a kiddie concert this afternoon."

Okay, back to Orchestra Baby Boomer.

Among the musicians I helped to prepare for the series of classroom visits by OBB artists, were two French horn players. I thought that our work together went very well, and I had the chance a month or two later to observe them in action in a classroom.

I thought these two players did a terrific job. They were well prepared, communicated extremely well with the students and each other, engaged the teachers, were clearly connected to what was happening before their visit and cognizant of what was to follow. Most important, the kids were clearly engaged, and well, I thought to myself that this was about as positive a classroom environment for teaching artists as I had ever encountered.

The kids were fully prepared, already knowing much of the basics about music and orchestra literacy, including the instruments, the composers being performed, who the players were, who the music director was, and much more. The kids had prepared some of their own materials including the instruments they created and music they had brought in for their own sound museum.

It made me think back to some of my early days as a teaching artists where I often encountered the exact opposite, which created a series of formidable challenges requiring you to explain so very much in order to establish some sort of basic shared context.

So, to make a long story short, I thought these two players were very lucky indeed. And you know what, I was feeling pretty darn good about it all.

And then came the time to talk with the players afterward, for us to share our feedback with each other.

And then, bang, it happened: the principal horn of Orchestra Baby Boomer said to me, "why do the big guns have to do this work?"

Utterly confused (think Beavis), I replied: "excuse me?"

He repeated what he had just said, and added, essentially, that he didn't see why he, as principal horn, had to perform in a classroom, and that while he didn't mind the children's concerts at the concert hall, this was basically beneath him.

I was stunned. Not the least of which because of all the seemingly positive work I had just witnessed.

Ultimately, what was being said was that the value system of this artist only recognized work from the main stage, and that anything off the main stage didn't have value--the main stage meaning a formal concert from a stage with a traditional setup for the audience.

The thing that I found most difficult to swallow about all of this was that the kids in that classroom were deeply engaged, all of them, as well as the teacher. But that didn't matter. What mattered was the setting.

To be honest, I didn't see much point in arguing. What the artist wanted most from me was to argue his case with managment, the case that the big guns should not have to do such work; that ultimately, it was beneath them.

Am I criticizing the Detroit Symphony musicians for what on the surface appears to be a resistance to service conversion? Service conversion basically means that a service required by the orchestra as part of its contract with the musicians would be extended to include education/community concerts/residencies, etc., and that such activities could substitute for formal concerts and rehearsal. In other words traditional services. I realize that's a rather simplified statement, that leaves out the nuances of how many services can be converted, etc., but still, that is what's at the heart of it.

So, am I criticizing it? Not necessarily. I understand it, both as a negotiating issue and in a cultural/historical context. There are those who see each change like this as part of a death by a thousand cuts. In this case it's the death of what has come to define a top tier orchestra in America.

While I will reserve any criticism for what is a very difficult situation in Detroit, I will offer instead my sadness for the continuing divide between education and the arts, and of course, for the cancellation of the remainder of the Detroit Symphony's season.

Most of the time I write about the divide it in terms of arts education failing to find its footing in the larger world of public K-12 education. This time it's different, it's arts education failing to find its footing within the field of the arts, and for that I am saddened.

The measure moving through the House includes a more than 16 percent cut to the Education Department's discretionary budget for the current fiscal year, including scrapping more than a dozen K-12 programs and slicing others once considered untouchable, such as Pell Grants to help low-and moderate-income students pay for college.

And what does anyone think will happen to the relatively small arts education grant program at the USDOE??

I strongly urge you to read Paul Krugman's piece in today's New York Times: Willie Sutton Wept

The whole budget debate, then, is a sham. House Republicans, in particular, are literally stealing food from the mouths of babes -- nutritional aid to pregnant women and very young children is one of the items on their cutting block -- so they can pose, falsely, as deficit hawks.

What would a serious approach to our fiscal problems involve? I can summarize it in seven words: health care, health care, health care, revenue.

What's next? Look for the elimination of the Education Department. That proposal is just around the corner.

On the face of it, yes, it's true: the NEA, NEH, CPB, PBS, etc., are all on a big hit list for zeroing out by any number of conservatives.

But, is it the reemergence of the culture wars? I am not so sure.

If you look at that hit list compiled by the Republican Study Committee, what you see is something much larger than a culture war. Legal Services Corporation? Gone. Amtrak? Gone. Ready to Learn TV program support? Gone. Mohair support? Gone. (Okay, while I love my mohair sweaters, I will give them that one.) Beach Replenishment? Gone.

Gone. Gone. Gone.

Here's the list.

In all fairness to the Study Committee, I don't think they're singling out the arts. I think it's something much more profound, essentially using the current economic crisis, caused to a large degree by unpaid for tax cuts, the two longest wars in US history, a lack of enforced regulations and deregulation of the financial sector, a giant unpaid increase to medicare (prescription drug benefit), and more, as an perfect excuse to roll back The New Deal.

Think of the Hoover era, and there's the goal. The GOP fought FDR tooth and nail on everything he did, and for anyone who has ever thought that particular battle was ancient history, think again.

Just as the Army was ordered by Hoover to police the Bonus Marchers, and we know how well that worked out, you've got the new governor of Wisconsin threatening to call out the Wisconsin National Guard.

It seems to me, that the list is really just a starting point.

The "Second Bill of Rights," here's the key excerpt, as proposed in 1944 by a very weary President Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people--whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth--is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights--among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty.

As our nation has grown in size and stature, however--as our industrial economy expanded--these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.

We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. Necessitous men are not free men. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all--regardless of station, race, or creed.

Among these are:

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

Americas own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for all our citizens.

For unless there is security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world.

Which arts should we invest in? All of them! While almost all arts correlated with increased success as a scientist or inventor in our study, lifelong involvement in dance, composing music, photography, woodwork, metal work, mechanics, electronics and recreational computer programming were particularly associated with development of creative capital.

Click here to read End of Art in School Means End of A Legacy, from the Toledo Examiner.

There was a radio interview with one of the Board of Education members and when they were asked when the child will be introduced to music the person said "...they can learn in church..."

And of course, the Common Core Standards has received a great deal of attention. It's here to stay for quite a while.

That being said...

The other day, as we were working on a grant proposal for the New York State Council on the Arts, we had an interesting discussion concerning the recently revised NYSCA guidelines:

All projects should relate to one or more of the statewide Standards for Arts Education and/or the new Common Core StandardsIt's the very first time that we've encountered the ELA and Math Common Core Standards, or any non-arts standards allowed as replacement standards for state arts learning standards that are still in effect.

Now, some of you, in states like Arizona, Kansas, South Carolina, Texas, and Washington, might say: who cares, at least you still have a state arts council. Fair enough. (I know, they're just threatening elimination in most of these states.)

But still, you have to admit it's quite the new development in the world of learning standards, don't you think: ELA and Math standards allowed as a replacement for arts standards.

Is it a harbinger of things to come or a notable exception??

As a follow-up to Chloe Veltman's recent piece on how youth choirs are flourishing despite cuts in arts education, Schulten asks the students to respond to:

Does your school offer classes in music, drama, dance or the visual arts? What experiences have you had with arts classes yourself, whether in or outside of school? How important do you think arts education is for students in general? Why?Here are a couple of excerpts from the responses:

My favorite class in all of my high school career was probably my music theory class in junior year. The class was a blissful break from the typical structure of the typical math and science class. It taught me, not only as a musician, but as a student, to be a more creative and resourceful human being.

Important? Absolutely! In fact I wrote an entire paper for my Argument Class on the subject that might be interesting for ya'll. http://www.creativetutors.com/b2evo/blog1.php/2010/09/06/why-teach-the-arts

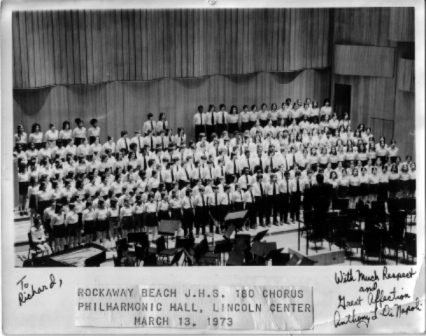

And, in the category of bigger is always better, here's a picture of my 200 plus member Junior High School Chorus. Take that, Glee!

It's a very important read, as it tackles the emerging mythology on how China goes about educating its students:

Is it true that "China and India started educating their children earlier and longer, with greater emphasis on math and science?"

No, China has actually started to reduce study time for their children, with less emphasis on math and science

I am not familiar with education in India so I will stick to China and I assume President Obama meant education in schools, not education at home. Unless he meant 50 years ago, the statement is completely false. The school starting age in China has remained the same at age six since the 1980s when China's first Compulsory Education Law was passed in 1986. Since the 1990s, China has launched a series of education reforms aimed at reducing school hours and decreasing emphasis on mathematics.

Here's another tease, just to make sure you click on through:

I know that many of the Dewey21C readers were probably thinking that the recent reports on how the US performs on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) would augur an even greater feeding of the educational industrial complex build on standardized testing in ELA and math.Is it true that Race to the Top is the most meaningful reform of public education in a generation?

Again, it depends. It depends on how one defines "meaningful." If defined as the scale of impact without questioning whether the impact is beneficial or not, it may be true but considering the actual consequences, Race to the Top is neither meaningful nor flexible. It does not focus on "what's best for our kids" nor spark "creativity and imagination of our people."

While I cannot say that fear is unfounded, it certainly helps to read Yong Zhao's blog...

So, it was cause for me to repost a blog entry about the composer Steve Reich. Okay, I was waiting for an excuse...

Enjoy!

_____________________________________________________________________________

Last week I was talking with a middle school principal in one of CAE's programs. A partnership school network planning meeting was concluding and we got to talking about quality. At first, I thought he was asking about quality arts instruction, as in "how do you support and measure it?" It's the sort of question you want principals to ask. Very quickly the conversation went to a deeper, more interesting, and entirely affirming place: "how can you tell quality in art?"

It's the mother lode. It's the conversation in education you point towards, hope for, far beyond the technicalities of a school principal administering an arts education program.

We got to talking about the age old issue of works that have passed the test of time, graduating to that of masterpiece, as opposed to newer works often by living artists, that are rejected outright or overlooked by those who are guided by the magical canon of masterworks.

We talked for a while about the length of time it took for Mahler's works to enter the mainstream, ultimately becoming accepted by audiences as masterpieces. These works, written at the turn of the 20th century, took a good 70 years or more to enter the classical canon. For most of these years, Mahler was relatively obscure.

We talked about Bach all but disappearing until Mendelssohn resurrected his works (Mahler pun intended) among classical music enthusiasts of the 19th century.

We talked about the people who still question Jackson Pollock. We talked about Buster Keaton, and the many years his body of works languished, until James Agee's 1949 Life Magazine piece put Buster's genius back on track with the American public.

It all got me to thinking about how I learned to love Steve Reich.

The vast majority of Western music has a similar architecture or design. It's there in a Strauss opera, as well as a great song by Gershwin or even a phrase of Woody Guthrie. The music of Steve Reich does not make use of that architecture. Its influence comes from Africa. It has a steady pulse, and phrases that appear to be repeating themselves, over and over. Reich describes it as 'pulsitile." In fact, these repeating phrases contain small, almost imperceptible changes that alter the music subtly over time. I would argue that if you can hear these changes, than you really aren't taking the music in.

Steve Reich on "pulsitile": Well, thirty years ago I had just returned to New York City from San Francisco. Basically, John Cage was the most important thing in town; Morton Feldman was active; The younger people were James Tenney and Phil Corner and Malcolm Goldstein, and Charles Wuorinen. At that time, the American composers were either under the "downtown" influence of John Cage or the "uptown" influence of Boulez, Stockhausen, Berio and company. But the sad fact is that musically, everybody was under the influence of music that was not "pulsitile," [not with a regular beat]. You can't tap your foot to either Boulez or John Cage, nor could you know where you were tonally. The idea of cadence, any sense of tonal center, melody in any sense of the word -- including even some Schoenberg -- was pretty hard to put your ear on. So I felt sort of out of it and very much alone.

Are you still with me? Okay, here's the deal: Reich's music does not employ the narrative that is prototypical to most Western music. If you're looking for the building of phrase, harmony, rhythm to an emotional peak, well, you won't find it in Reich's music. If you're listening for that Western narrative, you are SOL. You will find something else which asks you to receive the music in a different way.

In the mid-eighties, one of my dearest friends, freelance trumpeter Terry Szor, gave me a cassette of Music for Eighteen Musicians. He told me: "it changed my life." It's the turn of a phrase I have heard spoken about Reich's music so very, very often. So, I tried it on for size; I hated it.

I was listening for that Western narrative. In arts education, artists and teacher often work with the parallels between the architecture of sentences and paragraphs in literature (English Language Arts) and music. Naturally, settings of literary works to music, such as Schubert lieder, reinforce this relationship. That being said, if you were to compare Reich's music, or Coltrane's Interstellar Space or Sun Ship to such literary works, you might not know where to start. I chose these examples because Reich was influenced by the later, "experimental" works of John Coltrane, which are rarely mentioned against Coltrane's more traditional works, such as the beloved Blue Train or My Favorite Things.

God, this is a long blog....I hope you'll read it!

So, here I was listening with my Western ears, getting supremely bored (Coltrane pun intended), increasingly annoyed, and I quickly bailed, wondering what exactly was wrong with my friend Terry. Years later, after I finally learned to love Steve Reich, I played a recording of Drumming for another close friend, who got mad, I mean really mad, and instructed me in no uncertain terms to turn it off, immediately! At first I thought she was kidding, and laughed. It was not well received, to say the least.

The first time I recall really learning to love Reich's music was at a dance performance. There was something about following the dance, the visual aspect, that allowed me to take the music in, in an entirely different way. I wasn't listening for a certain progression, a certain phrase, a certain architecture--all the things I had been trained to listen for in music, but instead I felt the music, received it--allowed it to wash over me. Watching the dance made it possible. It was as if a switch was flipped: the override switch to shut off my Western trained musical mind.

This letting go of my intellectual ear, my thinking ear, perhaps better put, led me to a place where the music created a feeling that I could only describe as euphoric and trance-like, if, and only if I really gave in to it. Time and space sort of stopped, and I connected with the genius of Steve Reich. I learned to love Steve Reich.

It's what makes this question of quality difficult to answer in the simple way that an educator might like. Not to mention the question of assessing knowledge. Can't we create a rubric for this? The rubric of genius! How could it be that I moved along a continuum of experience and learning to evolve from someone who wanted Reich's music stopped, to someone who experienced a physical euphoria while listening to the work, wishing the music would never stop?

And, this isn't limited to Reich. To this day, I hear from the people who tell me that John Cage's genius is for his "ideas," not his music. Oh really?

I want to tie this back to education. Arts education, as well as education in general. The complexity of this matter, the kaleidoscope of quality, in so many ways speaks to the complexity of teaching and learning, and of course, how we evaluate, test, measure, and establish systems of accountability.

Is Andy Warhol genius or charlatan? Is Reich a genius or a bee buzzing your tower? Can standardized testing ever be an effective measure for understanding a complex world of teaching, learning, and human development? Perhaps when that task force or administrator gives us our rubric of genius we will know for sure. And for those who think I am kidding, believe me, that rubric is being worked on somewhere, someplace.

_____________________________________________________________________________

For those interested:

here's a link to me interviewing Reich in 1998.

And here's a link to Reich interviewing me (really!)

Sounds good.

For the portion of K-12 arts education that is connected to the arts and cultural sector (as opposed to school faculty, a distinction that underscores the complicated nature of arts ed), the overall calculus to the market forces is simple: schools purchase arts education services and the organizations raise funds to offset the cost of the services not covered by the fees from the schools. As the historic cuts to state budgets decimate education funding, prompting many to believe we are in a "reset moment," contracted services will decline even further. Add to this, the declines in fundraising reported across the entire non-profit sector. Yes, some of the foundation funding will start to increase, as a result in the growth of the stock market. But not so fast; I am sorry to predict that foundation giving will not return to pre-2008 levels for the arts and arts education, as the tremendous growth in charter schools and other variants of school reform will cause a diversification in foundation, individual, and corporate giving. To be fair, many of my colleagues and friends tell me that particular prognostication is overstated and not based in data.

If you want to get a sense of how profound some of the state cuts will be, click on through to Ed Week's coverage of what's happening in Texas, and even if you can't read the entire article as a non-subscriber, the tease is more than enough.

We're living in a time a extraordinary flux, and the greater field of the arts is feeling it in appropriately extraordinary ways. Whether it be the economy, technology, business models, tastes, generational shifts, most everyone recognizes the change and many are struggling to keep pace, while hoping to take advantage of it.

I believe the field of education may be even more dynamic right now, and as next year brings state budget cuts to education the likes of which we haven't seen since the 70s, there will be a super fuel added to the change that will present one of the greatest opportunity-challenges in a very long time.

If we're to commit further to advancing arts education, at the very least we should do it the right way and make sure it is for the benefit of the kids (and ultimately society), and hope that it just might have some sort of ripple effect in arts participation some years down the line.

Years back, when I was regularly involved in helping artists prepare for work in K-12 schools and the community, I often said that if they would be sensitive to how children were responding to the arts they were bringing to the classroom, that they would learn a great deal about how people respond to art on a fundamental level.

It was part encouragement for the teaching artist and part a tip on how to become more tuned to the arts and human experience. Ultimately, I believe that work with K-12 students will make for a better artist.

And, I have always been interested in the issue of new work for young people. It was something I wanted to develop during my days at The American Music Center--a commissioning program for new music and young people, but alas...

Belinda Reynolds, a terrific composer and member of the arts community in the Bay Area, has written a splendid piece about composing for young people that was recently published on my very favorite new music website, NewMusicBox.org.

I think there's a lot to think about in what Belinda has presented and here's just a tease, I hope you will click on through and give this one a good read:

Why is there still an oversight in composing for children? Does it have to do with our training as composers? Most of us were never taught how to compose music for an elementary technical level. In my own experience, not once did any of my beloved teachers discuss the issues surrounding writing for young players. I had the privilege of going to two top schools: one a university, one a conservatory. I was shown all the possibilities of what instruments can do. I was exposed to writing for incredible players. But, never was I introduced to writing for less skilled musicians. I was never encouraged to compose for any level lower than that of the professional player. It was simply overlooked.