Dewey 21C: December 2009 Archives

So, what does this all look like?

Here is the proposal summary:

NYS Race to the Top Summary

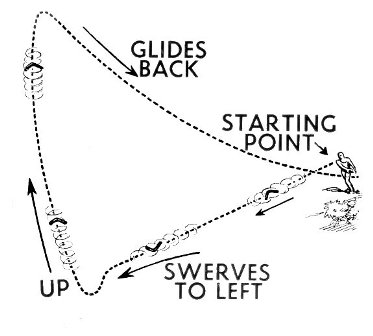

1. The school district leader says that the overall school budget is increasing each year, and not to worry. And yes, it's true: more money was allocated to education in the city budget.

2. The existence of generally supportive school district officials and government leads to increased arts budgets and administrative capacity within the district arts office.

3. Overall, things seem to be improving.

Looking at these three real occurrences, it's easy to see how building work in arts education advocacy would become a back burner issue.

Essentially people are saying or thinking: things are improving, going in the right direction, advocacy would be a waste of time and, in fact, it may only be seen as a hostile or arrogant approach, not to mention a waste of money.

Let's look at another set of circumstances.

The economy is in decline. School budgets are tumbling along with everything else.

So, what do you hear?

Advocacy would be a waste of time, in fact, would be seen as being out of touch with the harsh reality that everyone is facing. And, what will it get you in the end, except being viewed as being hostile and unproductive.

"Work with us," is what the powers that be say. (Can anyone guess what "work with us" really means?) Email guesses are encouraged...

So, where does it leave you if you shouldn't advocate when times are good nor when times are bad?

A sinkhole perhaps?

Or, the tumbling economy created demand for advocacy, but the work takes time and can't be effective long-term when put together overnight.

Where does that leave you?

A sinkhole perhaps?

So, exactly what is the counter-intuition, you may be asking?

You build the necessary advocacy capacities during the good times.

That's it.

Plus, you have to advocate all of the time.

Third, it's a bit hard to accept that standing firm for what you believe in is going to ruffle some feathers. Those who really know this work view the feather ruffling as evidence of success. There's a tad of counter-intuition there as well.

And finally, I leave you with a thought, one that I will come back to:

The kids that get the most arts (and other necessary support and care) in the home most likely get it at school as well.

The kids that get the least arts (and other necessary support and care) in the home most likely get the least in school.

The director is the artist Andrea Dorfman. The music is by Tanya Davis.

Click away, it's a sweet and appealing video, and even if you don't like the style of music, I dare you, double dare you, to say you don't like the message.

To read Jane's previous entries, all you have to do is search using the little box to the right and voila! --RK

*********************************************************************************************************

I have said for many years that some of the best professional development occurs when experienced classroom teachers and visiting artists sit down together to figure out how to make authentic and profitable connections between an arts course of study and the general curriculum. Back in the days (sixties to early seventies) I was asked to create what the Feds called an innovative and exemplary artists as resources program for the then Lincoln Center Student Program (the precursor of the current Lincoln Center Institute). Over the years, we identified, developed, coached and monitored close to several hundred professional artist musicians, composers, dancers and actors whose job it was to collaborate with classroom teachers in the preparation of students for a whole panoply of Lincoln Center performances both at the Center and in school classrooms and auditoriums.

The challenge then remains the same today: how do you build understanding and ultimately good practice that will encourage student learning in and through the arts between artists, most of whom have little knowledge of pedagogy, child development and the regularities of schooling and classroom teachers, most of whom have little knowledge of the performing (in this case) arts, their history, and the artistic process. The answer has been very slowly, and not very well, with a few stunning exceptions when arts specialists join the discussion and the team, when classroom teachers have an arts background, or when artists have public school teaching experience.

Most of the professional development for artists continues to be conducted by other artists, with an occasional nod to classroom teachers and school-based arts educators. The problem with this approach has been apparent for years: we expect to build "effective" classroom partnerships by dealing mostly with only 50 percent of the team - the artist. This usually results in the artist displacing the classroom teacher or arts educator who retreats to the sidelines, afraid and unequipped to figure out ways to collaborate. Very few artists of the hundreds I have known and worked with can work at the top of their game under these conditions, so connections tend to go un-made and learning in both the arts and other subjects suffers. There are many ways to change the lopsided paradigm, most of them productive if time-consuming and expensive. I was reminded the other day of one of the strategies we used regularly "back in the day" which I now share with you.

An artist new to a year-long residency was struggling with school regularities, classroom management and appropriate methods of reaching and teaching certain principles and skills to the students. When we brought two of the experienced teachers in the program together with the artist who was eager for the discussion, the entire dynamic of the conversation and the focus of the discussion changed, immediately. The artist posed a question or two about classroom practice, and the classroom teachers responded abundantly, articulately and with stunning clarity. The balance of power (yes, power) had shifted, for the moment, from the artist (who is deferred to in most residencies I see these days) to the two teachers who gave us specific classroom example after example of what might be done, how, when and under what circumstances. The artist took copious notes jotting down the pearls of wisdom, raising an occasional question, and finally coming up with a tentative plan to move the work and the program in clearer and now more consensus-built direction. The discussion had ranged from management, to method, to content, to structure and goals and ways of bringing the arts and the other subjects into unforced alignment.

At the end of almost ninety minutes (the teachers were "covered" with subs), we all broke into applause and bravos. We agreed it was probably one of the best P.D. sessions we've witnessed and been a part of in years. And, it cost practically nothing extra. It is likely that this "mere" hour and a half will change the course of the work for the rest of the school year, especially if we stick to our practice of meeting as a full team every month or so.

Moral of the story: In a classroom partnership leadership needs to be evenly distributed and this includes balancing teachers teaching artists and artists teaching teachers, to the enormous benefit of their students (and their parents, when you can include them in the process.)

Jane Remer

December 10, 2009

***********************************************************************************************************

JANE REMER'S CLIFFNOTES We are at another rocky precipice in our history that threatens the survival of the arts in our social fabric and our school systems. The timing and magnitude of the challenges have prompted me to speak out about some of the most persistent issues in the arts education field during the last forty-plus years. My credo is simple: The arts are a moral imperative. They are fundamental to the cognitive, affective, physical, and intellectual development of all our children and youth. They belong on a par with the 3 R's, science, and social studies in all of our elementary and secondary schools. These schools will grow to treasure good quality instruction that develops curious, informed, resilient young citizens to participate fully in a democratic society that is in constant flux. I have chosen the title Cliff Notes for this forum. It serves as metaphor and double entendre: first, as short takes on long-standing and complicated issues, and second, as a verbal image of the perpetually perilous state of the arts as an essential part of general public education. I plan to focus on possible solutions and hope to stimulate thoughtful dialogue on-line or locally.

************************************************************************************************************

Jane

Remer has worked nationally for over forty years as an author,

educator, researcher, foundation director and consultant. She was an

Associate Director of the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund's Arts in

Education Program and has taught at Teachers College, Columbia

University and New York University. Ms. Remer works directly in and

with the public schools and cultural organizations, spending

significant time on curriculum, instruction and collaborative action

research with administrators, teachers , students and artists. She

directs the Capezio/Ballet Makers Dance Foundation, and her

publications include Changing Schools Through the Arts and Beyond

Enrichment: Building Arts Partnerships with Schools and Your Community.

She is currently writing Beyond Survival: Reflections On The Challenge

to the Arts As General Education. A graduate of Oberlin College, she

attended Yale Law School and earned a masters in education from Yale

Graduate School.

Jane

Remer has worked nationally for over forty years as an author,

educator, researcher, foundation director and consultant. She was an

Associate Director of the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund's Arts in

Education Program and has taught at Teachers College, Columbia

University and New York University. Ms. Remer works directly in and

with the public schools and cultural organizations, spending

significant time on curriculum, instruction and collaborative action

research with administrators, teachers , students and artists. She

directs the Capezio/Ballet Makers Dance Foundation, and her

publications include Changing Schools Through the Arts and Beyond

Enrichment: Building Arts Partnerships with Schools and Your Community.

She is currently writing Beyond Survival: Reflections On The Challenge

to the Arts As General Education. A graduate of Oberlin College, she

attended Yale Law School and earned a masters in education from Yale

Graduate School.*************************************************************************************************************

The document itself must be applauded for all the work that went into it. In this difficult economy, the mere existence of this report must be given its due.

The point of this blog entry is to push the NYCDOE to dig deeper, for the sake of our students and their families.

If you want to read the really good news, here's the press release. It's a work of art in the very rosy picture it portrays. Of course, that rosy picture is at the core of what disturbs many people I know outside of the NYCDOE. It just doesn't completely add up. One colleague said to me right after the presentation that he felt very confused. Another said that it was counter-observational. Another recognized some of the data issues outright and said that it was a rather artful piece of politics. Hence the cognitive dissonance.

Okay, if you read the press release, as I said, you can get the good news. And yes, there is some good news in the report, but, one cannot gloss over the not-so-good news.

Here's some of what you won't read in the release:

1. The report says nothing about equity. There are no demographics on income, race, etc. For a school district that looks at this data in other areas as part of their focus on ending the achievement gap, the divide between what is looked at in the arts and what is looked at in ELA, math, and graduation rates is rather remarkable.

2. The data on middle schools calls into question the reliability of some of the report's findings. People are scratching their heads trying to understand how more than three years of reductions in the number of certified arts teachers at the middle grades, combined with two years of deep declines in spending on services of cultural organizations and spending in supplies, instruments, etc., can possibly result in a 17% increase in the number of schools that are providing all of their students with the minimum state requirements in arts education. And, bear in mind that credit for these requirements can only be satisfied by a certified arts teacher.

3. The declines in funding to arts education and cultural organizations are both steady and alarming. The trend, the lion's share of which began before the economic crisis and any real cuts to school budgets, has many people wondering what future these organizations have in working with NYC public schools.

4. The report presents rather positive data on the hiring of arts teachers at the elementary levels, and overall, an increase in the head count of arts teachers by 79. This is also one of those data points that makes you wonder. Certainly, if we could see a breakdown of the number of teachers lost to attrition, the number of teachers who were excessed and placed in the ATR pool, and the number of teachers in the Rubber Rooms, we would have a more complete sense of exactly what is happening with the number of certified arts teachers in the system.

5. The report notes that overall spending on the arts went from $311 per student to $316 per student. Presumably this increase was due in large part to the cost escalation of teacher and administrator compensation. $316 per student? This data point is provided in order to refute the calls to restore Project ARTS.

Let's look a bit more closely at this. What the NYCDOE is saying, basically, is that Project ARTS which averaged around $65 per student, as a required minimum level of spending, is now dwarfed by the big bold figure of $316 per student. This substantiates their claim that Project ARTS is meaningless. Sound right, don't you think?

Well, first of all, this is really comparing apples to oranges. The number they are providing is some sort of average of all costs associated to arts education divided among all students. But what is the real number per student per school? What about schools with practically nothing versus schools like LaGuardia or Art and Design? What was this aggregate number during the years of Project ARTS? How much has it gone up or down in terms of real spending, while separating out the increases to teacher and administrator salaries. There are many aspects of this that need to be looked at further before opening the bottle of champagne to celebrate the demise of Project ARTS.

5. There is a lost opportunity by not comparing this report to the School Progress Reports and Quality Reviews. How are those schools that received A's doing in arts education? This would tell us a great deal about exactly how much Arts Count, the arts accountability initiative of the NYCDOE, really counts.

6. The report has the very same Achilles heel that you see in other such reports. It relies too heavily on what was offered as opposed to real rates of participation. A school may offer art, but what percentage of students actually participate?

One way or the other, I applaud the hard work of the talented and dedicated OASP staffers and urge everyone involved to take this effort to the next important level.

Here are a few data points you may find interesting:

• At the elementary school level schools budgeted $2.5 million (73 percent) less for arts supplies, materials, instruments, etc. than 2006-07 (the first year the report was issued); budgeting to hire the services of arts and cultural organizations has declined $3.7 million (33 percent).

• At the middle school level schools budgeted $2.7 million (80 percent) less for arts supplies, materials, instruments, etc. than 2006-07; budgeting to hire the services of arts and cultural organizations has declined $2.9 million (53 percent).

• At the high school level schools budgeted $1.8 million (50 percent) less for arts supplies, materials, instruments, etc than 2006-07; budgeting for the services of arts and cultural organizations has declined $1.1 million (35 percent).

Finally, a comparison of the high school data provided in the last three Annual Arts in Schools Reports shows that there have been steep declines in the percentage of students that have taken three or more credits in the arts, from 46 percent in 2006-07 to 32 percent in 2007-08 to a low of 28 percent in 2008-09. This is particularly interesting as it raises a number of questions about a disconnect between the creation of the Chancellor's Endorsed Diploma for advanced arts study at high school and the decline in the number of students qualifying for this diploma.

There was an interesting piece on the Partnership for 21st Century Learning in last week's Ed Week. In fact, this story is still on the home page of Ed Week. As more and more of the arts education field signs on to P21, it's worth giving this a good read.

Whether P21 can successfully convince skeptics of its good intentions remains an open question. Concerns about a lack of specificity in its materials are no longer the sole province of core-content advocates like Ms. Munson, but also now include educators in the career and technical education arena.Last summer on the Core Knowledge Foundation blog, my dear friend Diane Ravitch posted an absolutely brilliant entry called The Partnership for 19th Century Skills. It occurred to me when I read the recent Ed Week piece that I hadn't shared Diane's piece with you.

It is a must read, for its brilliant wit and perfection as a critique.

Here's a the meat of the blog:

This partnership will advocate for such skills, values, and understandings as:

- The love of learning

- The pursuit of knowledge

- The ability to think for oneself (individualism)

- The ability to stand alone against the crowd (courage)

- The ability to work persistently at a difficult task until it is finished (industriousness, self-discipline)

- The ability to think through the consequences of one's actions on others (respect for others)

- The ability to consider the consequences of one's actions on one's well-being (self-respect)

- The recognition of higher ends than self-interest (honor)

- The ability to comport oneself appropriately in all situations (dignity)

- The recognition that civilized society requires certain kinds of behavior by individuals and groups (good manners, civility)

- The willingness to ask questions when puzzled (curiosity)

- The readiness to dream about other worlds, other ways of doing things (imagination)

- The ability to believe that one can improve one's life and the lives of others (optimism)

- The ability to believe in principles larger than one's own self-interest (idealism)

- The ability to speak well and write grammatically, using standard English.

''I'm convinced when students are engaged in the arts, graduation rates go up, dropout rates go down,'' Duncan said.One thing we do know about graduation rates and arts education in New York City public schools, is that the schools that offer more arts have higher rates of graduation. It's in this report.

And, according to The New York Times, Duncan indicated that the re-authorization of NCLB would recognize what parents, teachers and students have all noticed: "a narrowing of the curriculum."

It's all here in CAPITAL CULTURE: Obama Drops Cautious Arts Policy.

Okay, now that Duncan is sure about arts leading to higher graduation rates and he also stands firm on high stakes testing leading to a loss of arts education, maybe, just maybe he might revise the Race to the Top guidelines for the second round to support arts education in the way the first round is supporting STEM subjects.

I call that first round: "the missed opportunity."

Let's just imagine what might be possible had the guidelines for RttT provided any sort of opening for arts education. It would have been a game changer. That's what the USDOE is capable of right now, with all that money that will flow to state departments of education and school districts. By simply carving out a part of the RttT guidelines for arts ed, it could have changed policy/practice in the most remarkable way.

I'm not claiming my second education has been exemplary or advanced. I'm describing it because I have only become aware of it retrospectively, and society pays too much attention to the first education and not enough to the second.

I like David Brooks. Okay, I have to admit it, I like him even more since reading this column that many have missed because it appeared during the T-Day break.

David Brooks on arts education? Really? "But I read him regularly and haven't seen anything of the sort," is what you may be thinking.

Bait and switch? Not exactly.

The Other Education, was published on Thanksgiving Day. It appears, that Brooks has something more to be thankful for than a turkey dinner, and that is Bruce Springsteen.

We don't usually think of this second education. For reasons having to do with the peculiarities of our civilization, we pay a great deal of attention to our scholastic educations, which are formal and supervised, and we devote much less public thought to our emotional educations, which are unsupervised and haphazard. This is odd, since our emotional educations are much more important to our long-term happiness and the quality of our lives.Through Springsteen, David Brooks embarked on a new education.

What mattered most, as with any artist, were the assumptions behind the stories. His tales take place in a distinct universe, a distinct map of reality. In Springsteen's universe, life's "losers" always retain their dignity. Their choices have immense moral consequences, and are seen on an epic and anthemic scale.Fair enough, the article isn't exactly about arts education, but then again, it surely is. It speaks to why arts education is important. It also speaks to some of the things that an integrated approach to arts education can provide, but is often a bit tricky to measure.

As for Springsteen, I have to admit that I came around to his music just a bit on the late side. When his career really started taking off, I was busy at Juilliard obsessing over Bach, Mahler, and finding the right leather case for my trombone. In recent years, I have grown to view him as one of the greatest artists of our time--for his music, for his love of musicians and the artistic community, and for his commitment to placing his work smack dab within the social and political issues of our time. Want to talk about cultural relevance, as my friend Amanda Ameer sometimes does, well, look no further than to The Boss to understand what that phrase means.

Arts education needs to be incentivized through dedicated funding. Because the NYC public school system is not meeting even the most minimal standard requirements for arts education, the arts should be treated as a "protected class" of studies. When it comes to arts education, we need all of our schools to be winners. It is critical that the DoE create a dedicated funding line with budget allocations for schools to prevent more declines in arts education and capitalize on the benefits of arts education for children.

--Ernest Logan, President, The Council of Supervisors and Administrators

It is generally accepted that principals don't like categorical funding. However, there are exceptions to every rule, and the Council of Supervisors and Administrators (CSA), which is the union that represents principals, assistant principals, and other administrators in the New York City public schools recognizes that categorical funding for arts education is indeed one of those rare and important exceptions.

The categorical funding for the arts in the New York City public schools was called Project ARTS. Essentially, it worked three ways: it could be used to offset up to 50% of the cost of a new certified arts teacher; it could be used to pay for arts supplies; and it could be used to pay for the services of cultural organizations. Prior to its elimination, it was set at about $65 per student and it could only be used by a school for those three purposes. The funding that went to pay for cultural organizations was generally matched by private donations at a rate of three dollars to every one. It was commonly understood that Project ARTS spearheaded the hiring of well over a thousand arts teachers in the NYCDOE. Here are two briefing documents CAE created on this issue in 2007: Project ARTS Briefing Paper.doc; Project ARTS-a brief history.doc

In 2007, it was eliminated. Basically, the reason given was that it didn't work very well. We were told that it tended to ensure low quality arts education and that it also tended to cause principals to spend less on arts then they would without Project ARTS.

A year later, we were told that the reason it was eliminated had nothing to do with how it worked, for it worked fine. Instead, it was eliminated because the NYCDOE had plans to "empower" the principals to create and spend their budgets as they see fit. "We don''t earmark funds for reading and math."

One thing's for sure, with there having been no formal evaluations of Project ARTS by the NYCDOE, the basis for the decision was not driven by data.

At the time Project Arts was eliminated, we received many, many calls from school principals saying that it was a bad idea. Principals had used Project ARTS strategically: it helped them protect arts spending during a period of increasingly high stakes testing in ELA and math; it brought in extra dollars from private donations; and it helped them stretch to hire arts teachers by offsetting the cost of the new teachers with restricted dollars. This statement by the CSA affirms what we already knew.

In all fairness, the NYCDOE considers Project ARTS to still be in effect. You see, there is still a budget line for Project ARTS, but it's no longer dedicated to anything. For new principals who have entered the system since 2007, they don't even know what the term Project ARTS means. The NYCDOE also believes that there the elimination of Project ARTS has been a success by just about every measure.

Many people disagree.

Okay, for the moment, that's probably enough for you to know. And believe me, for everything I've mentioned in this long and somewhat convoluted blog entry, I am leaving out two or three vital things, including information about the campaign to restore dedicated funding.

The real news here is that CSA submitted testimony at a recent New York City Council hearing on arts education that dedicated funding for the arts should be restored.

This was a bold and important statement that branded the CSA as a powerful advocate on behalf of arts education in the New York City public schools. They recognize what many know to be true: that with the ways that the educational system is structured today, the deck is stacked against a subject like arts education, and that it needs something to help protect, sustain, and incentivize it in order to ensure that every child receives a high quality education that includes the arts. The great irony here is that something like Project Arts, when combined with some of the recent quality initiatives of the NYCDOE would make for a truly powerful and necessary combination that could really move arts education forward, particularly with this tough economy.

Here is the testimony. I hope you will download it, because in my view, it signifies a historic moment in arts education advocacy, made possible by the great leadership and vision of CSA.

With budget decisions now made at the school level, the mid-year budget cuts and deeper cuts planned for next year will back most school leaders against the wall once again: they are likely to feel forced to scale back arts programs even further in order to focus on mandated subjects, particularly reading and math. Considering the elimination of Project ARTS and the additional looming cuts to school budgets, we may be looking at a perfect storm brewing for arts education.

While CSA believes that Principals need a large measure of autonomy over the way they run their schools, we believe that the DoE must restore mandated funding for arts education for all NYC schools, in much the same way as it was mandated in the Project ARTS initiative.

One of the things I like to do with this blog is to bring to your attention things you might have missed. Here's one for ya:

Tips for the Admissions Test...for Kindergarten is a piece from last week's New York Times that looks at just how out of control the testing craze has become. But wait, there's more, as in more tests a comin'.

Here's a little taste of the article:

Private schools warn that they will look negatively on children they suspect of being prepped for the tests they use to select students, like the Educational Records Bureau exam, or E.R.B., even though parents and admissions officers say it quietly takes place. (Bright Kids, for example, also offers E.R.B. tutoring.)

"It's unethical," said Dr. Elisabeth Krents, director of admissions at the Dalton School on the Upper East Side. "It completely negates the reason for giving the test, which is to provide a snapshot of their aptitudes, and it doesn't correlate with their future success in school."

No similar message, however, has come from the public schools. In fact, the city distributes 16 Olsat practice questions to "level the playing field," said Anna Commitante, the head of gifted and talented programs for the city's Department of Education.

And there were a slew of Letters to the Editor. Here's a good one from Edward Miller, Founding Partner of the Alliance for Childhood:

Both the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test and the Bracken School Readiness Assessment are deceptively named. Neither one reliably measures young children's knowledge, ability, talent or readiness for school. Using these tests -- or any standardized test -- to sort children into groups of "gifted" and, presumably, "not gifted" is educational malpractice.

New York should follow the lead of North Carolina, which prohibits the use of public funds for standardized testing of children before third grade.

Edward Miller

New York, Nov. 21, 2009