Richard Kessler: October 2009 Archives

Mayoral Candidates Debate Arts Education in First Ever Arts Ed Questionnaire

Thompson Levels Harsh Criticism of Bloomberg Education Policy;

Bloomberg Emphasizes Progress and "A Lot of Work to Do"

NEW YORK, NY - October 29, 2009 --The Center for Arts Education today released the responses of mayoral candidates Bill Thompson and Michael Bloomberg to the first-ever NYC mayoral arts education questionnaire.

Mayor Bloomberg's responses emphasized the Department of Education's progress in installing measurement and training tools to help guide the city's efforts to ensure all students receive a quality arts education, while saying there was still "a lot of work to do" on that front.

Thompson leveled harsh criticism on Mayor Bloomberg's education policies. Vowing to "reverse Mike Bloomberg's misguided policies with a renewed commitment to providing quality arts programs to all our children," Thompson derided "Mayor Bloomberg and the DOE's failure to make arts education a priority" and called the City Department of Education's record on arts education "absolutely shameful."

"We must fix the curriculum so that we're not just teaching to the test but teaching the whole child," wrote Thompson. "With all its focus on improving scores, the DOE has lost sight of the true objective: improving schools by improving learning," he said.

Richard Kessler, executive director of CAE, said, "it's heartening to see that these candidates understand the importance of arts education in a child's learning and development. And it's vital that Mayoral candidates articulate a vision on issues that are so fundamental to educating the city's 1.1 million school children."

Thompson supported the following policy initiatives to address the lack of arts education in many city public schools:

The restoration of per capita dedicated funding for arts education at all city schools;

New York City Department of Education led remediation efforts or other interventions for schools found to be out of compliance with state arts education requirements;

- Inclusion of a wider array of factors, such as data from the Annual Arts in Schools Report, school compliance with state education requirements, and other in the school Progress Reports;

- Creation of a citywide task force to examine access to arts education offerings in city public schools.

Bloomberg noted several initiatives that have been implemented during his tenure or may be implemented in the future, including:

- The introduction of "Arts Count" - a series of metrics to measure and report on arts education in the public schools;

- The prospect for enabling small schools in the same building to share arts space spaces and teachers;

- Giving principals greater control of the budgets for their own school;

- Providing leadership training in the arts;

- A new Arts Education Reflection Tool to begin reporting on the quality of arts education.

The candidates' completed questionnaire responses are posted online at:

www.caenyc.org/mayoral-candidate-survey

Doug Israel, Director of Research and Policy for CAE, said, "We need to reinvigorate education with robust course offerings and teaching that grabs students' attention and makes them sit up in their seats. The arts provide an essential part of the school day and we believe it's critical to make improving the quality of arts instruction in the New York public schools an even greater priority during the next four years."

Responses from candidates for the office of New York City Public Advocate are also posted online all.

http://www.cae-nyc.org/public-advocate-survey

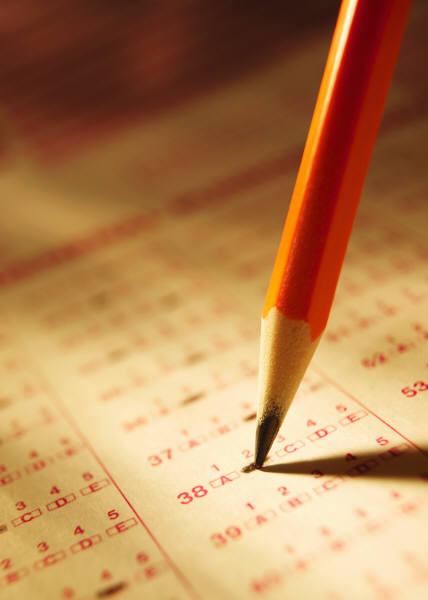

It is near impossible to be awarded one of these highly competitive grants unless you have a quasi-experimental research design as part of the overall project design. Essentially what makes it a quasi-experimental design is that it lacks a randomized control. It does have a control group (otherwise it would be a non-experimental design), and the common lens of research across all of these USDOE AEMDD grants is standardized test scores in ELA and math.

The USDOE is particularly interested in the question of how the project or let's use the term "treatment" will affect the ELA and math test scores for those students who participate versus students of similar demographics that do not.

Today more than ever, using the state ELA and math tests raises a very complicated question that you might not have dealt with or considered a few years ago. It is provoked by the test scores having risen dramatically across New York State over the past couple of years, in nearly every school district regardless of the approach of the individual district.

So, you've got scores catapulting across the State of New York, no matter what the treatment, reform, intervention, and here we are trying to measure our program using these very same test scores.

Yes, of course, the research will still report out on the differences between students in the program and those who are not. So, what's the big deal you might ask?

But wait, consider this: the gold standard of ELA and math assessment, the NAEP scores, are at odds with these increases. And there's even more, including a fair number of people in education who are either reporting or suspecting an increase in cheating, or scores being changed by educators as an outgrowth of the increasing stakes associated with these tests.

Do you see a problem?

No? Yes? Maybe?

All this has led many to question the validity of these tests. The Chancellor of the New York State Board of Regents, Merryl Tisch, recently addressed this issue by saying that the tests would be revised to make them less predictable.

So, you might have thought this post would be the usual jeremiad against standardized testing leading to a narrowing of the curriculum. Nope, this is an altogether different twist, essentially centered in fundamental questions about the validity of research components that are based on these test scores.

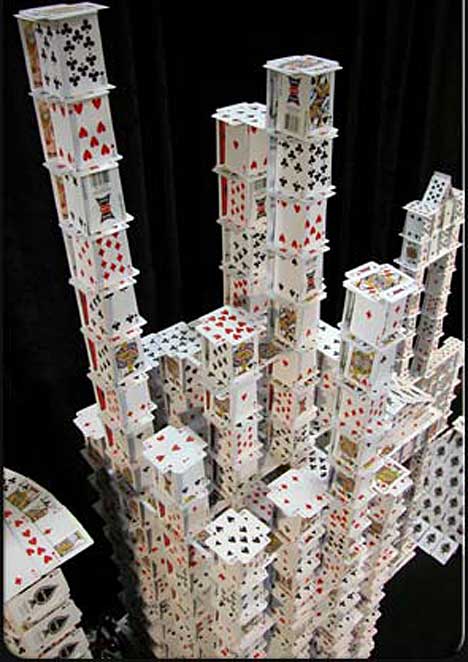

Now, to be fair, we are looking at a host of other issues, both qualitative and quantitative. But, when considerable questions are being raised about the standardized tests themselves, it positions whatever research you might be doing on the effects of your program on ELA and math tests to prospectively be an even bigger house of cards than ever before.

So, for the time being, if a principal doesn't want to support arts education, there's not much that's going to happen to change that. They really have no supervisors in a traditional sense. Most people view this as double-edged sword.

Some people think the narrowing of the curriculum is a myth. I think the most credible take on it is that the narrowing had already occurred before NCLB and that NCLB's effect on narrowing is most evident at low performing schools. That is indeed what the GAO found in a recent study.

One way or the other, the education-industrial-complex is built on standardized testing in math and ELA.

Okay, here's one example of curriculum narrowing. It's a story about a New York City fourth grader with solid test scores who has been barred from taking an after school dance class in order to focus on test prep.

With no one to go to except the schools chancellor, these parents chose to take this public. They didn't have a lot of options.

As they often say when your team loses: read it and weep.

Queens Child Devastated: She Wants to Dance But Put in Test Prep Instead, NY Daily News

Kelly did well on her report card from PS 207 last year, scoring Level 4 on the state math exam.

She passed the reading test with a Level 3, which her teacher's comment characterized as "Meeting grade standards."

Department of Education spokesman William Havemann characterized the younger Kelly as scoring "a low level 3" on reading and said the school was "ensuring that all students have the extra help they need."

There will be obituaries everywhere, as well as tributes. He footprint was all that.

I never had the privilege of meeting Mr. Sizer, but have read and been inspired by his work and vision, a vision that always seemed to reflect the complexity of what was at hand. And today, in so many ways, remains a counter-balance to the technical solution variant of school reform so evident all around us.

At the Center for Arts Education, Sizer's thinking was evidently behind so much of the first decade of work in school partnerships. This was work, in my humble opinion, that reshaped and reframed the entire notion of school partnerships with arts organizations (and post secondary institutions).

The work was based upon the needs and interests of local schools, and was not determined by one curriculum, framework, or blueprint--no matter how well liked or politically connected the document was. Guiding principles were established to provide some coherence, but in the end, the school community and its partners determined much of what they would do and where they would go.

This was all fueled by The Annenberg Foundation, which also fueled the Annenberg Institute for School Reform. While much of the school reform world likes to trash the Annenberg Challenge as one colossal failure, they don't often bother to look at the work of the three Annenberg Challenge organizations devoted to arts education. It's as if it doesn't really count. In many respects, that is a metaphor for the very place of arts education in schools then and now, and a good guide as to where we need to drive to as a field and hopefully one day, a movement.

Sizer was heading up the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, and naturally, his work and principles had an effect on the thinking of my very fine friend and colleague at CAE during this time: Hollis Headrick, Greg McCaslin, and Russell Granet, among others. Whether by explicit design or lurking in the background, the connection to Sizer is difficult to deny.

My takeaway about Sizer is that he was ultimately about the art and craft of education, and that was and will remain, refreshing, instructive, and central.

I have thought a great deal about quality of conversation. It is something I have been wanting to blog about. It is something I want to capture better, as a way of measuring, understanding, and communicating. What I mean specifically is how I am often deeply moved by the ways in which the quality of the conversation illuminates the development of understanding, shared language, individual and collective capacities, learning, programmatic objectives, skills, and so much more. It would be fair to say that it's the polar opposite of the standardized test.

And it makes me think, so very much, of the work of Ted Sizer.

I leave you with a a group of quotes:

It is an inescapable reality that students learn at different rates in different ways.That creates the need for a schedule of sensitivity that not only teachers close to the particular student can devise - not some theory-driven, central office, computer-managed schedule.

'We parade adolescents before snippets of time. Any one teacher will usually see more than 10 students and often more than a 100 a day. Such a system denies teachers the chance to know many students well, to learn how a particular student's mind works.

Only by examining the existing compromises in schools, however painful that may be, and moving beyond them, can one form more thoughtful schools. And only in thoughtful schools can thoughtful students be hatched. And this requires thoughtful leaders.

Schools are complicated places. Attitudes - those of teachers, students and others - must change as well as the structures of the schools in which they work. This takes time, political protection and patience.

When the students forget the explicit contents of today's lesson - and we know that they will - what is left? Anything? What happens after they forget the difference between atomic number and atomic mass? What is left after they forget the difference between the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? After they forget the rhyme and scheme and meter of a Shakespearean Sonnet or between sin, cos and tan?

Respect for students starts with respect for teachers, for them as individuals, for their work, and for their workplace.

I thought the most recent entry was fascinating, and would urge you to read it. This entry looks at school reform through the lens of teacher satisfaction and school culture. It was clearly provoked by a recent report released by Public Agenda that surveyed teachers nationally. The big headline here is:

Two out of five of America's 4 million K-12 teachers appear disheartened and disappointed about their jobs, while others express a variety of reasons for contentment with teaching and their current school environments, new research by Public Agenda and Learning Point Associates shows.Okay, back to the Ed in the Apple blog. First, I am not offering this to take sides for or against Joel Klein. Instead I am offering this up for what it says about how positive school culture manifests itself in how teachers organize within a school, as well as the statements about how positive school culture translates to a quality education.

These two consecutive paragraphs are particularly interesting:

School culture is the behind-the-scenes context that reflects the values, beliefs, norms, traditions, and rituals that build up over time as people in a school work together. It influences not only the actions of the school population, but also its motivations and spirit (Peterson, 1999).That last paragraph was a great glimpse into something you won't come across in run of the mill education policy fare. Why is it important to someone in arts education? Well, it tells you so very much about what's behind the school culture that you are working with. And for those of us that hope to have a positive influence on that culture, the more we understand, the better off we will be.

One of the ironies is that union activism and collegial school cultures are an inverse function. A highly effective school with a totally collaborative culture has a school secretary as the chapter leader, whose sole role is to post union notices on the bulletin board. Another school that uses lead teachers instead of assistant principals, a school in which teachers design and run the professional development, elects a chapter leader with little actual function. Schools with vibrant active chapters are frequently schools with toxic school cultures.

So, I hope you will click through to the Ed in the Apple blog titled The Intractable Power of School Cultures: Why Teachers Resist Chancellors and School Culture Determines Quality Education.

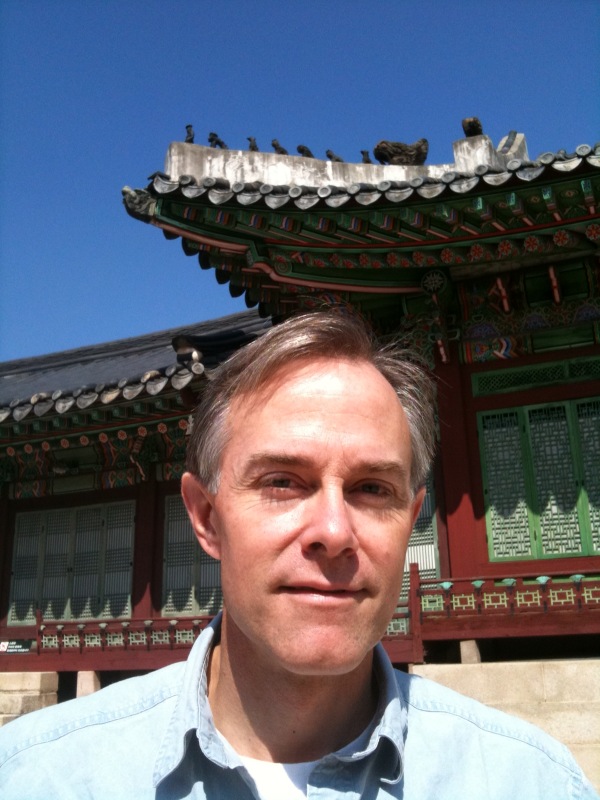

This is another wonderful entry from Ted, in what has become his arts education travelogue on tour overseas. Kids will be kids, wherever they may be. RK

***********************************************************************************************************

10.13.09

Are kids more alike or more different among widely different cultures? How much does the culture within which children grow up determine their learning style?

Based on several years experience with music education projects in Japan, China, Korea, and of course in the United States (both New York City and Vail, Colorado) I could easily argue either "more alike" or "more different."

Music composed by ten- to twelve-year olds through the New York Philharmonic's Very Young Composers program suggests remarkable similarity among kids in New York, Vail, China, and Japan. In a relatively short period of time, they accept the freedom thrust upon them and become engaged in developing sounds invented out of their imaginations. This is a potentially profound finding. At the same time, and nearly as striking, is the regional sound one can detect in the compositions. Thanks to the transparency of our process - Teaching Artists acting as mentor/scribes are scrupulous about not making or urging any compositional choices - one can readily hear the difference between, for instance, largely homophonic Chinese pieces and harmonically-based American pieces. Recently completed Japanese pieces are more subtle in their accent as they cover such a wide variety of styles and individual voices, yet it is there.

Also suggesting similarity is the reaction of groups of students to interactive concerts given by the Teaching Artists Ensemble of the New York Philharmonic in New York, Japan, and Korea. Younger kids all raise their hands having little to say; older kids may have lots to say, but never raise their hands. The same everywhere, and the same age-appropriate signs of engagement.

Arguing for greater difference among students in different cultures is the individual child's sense of ownership in a piece of music he or she has composed. Child composers in the United States can tend toward the ham state; in Japan, peer pressure against standing out makes some students intensely shy and can even lead them to deny having composed their pieces. Chinese student composers seemed to strike a gracious middle ground of pride in their works as contributions to a complete concert.

We have also been struck by the ability of Japanese students to remain silent in the face of a direct question or suggestion. For them it is better to be silent than to be wrong. American children rarely display such determined self-restraint!

On the other hand, the respect shown to teachers and all adults that we expect to see in Asian classes turns out to vary at least as much by the school as it does by the nation. In this area, the culture of the school seems to count for more than the broader culture.

I remain with considered "maybes" and "it depends" to the question of kids' difference or similarity. Cross-cultural work raises so many issues it can be difficult to determine even which ones are real. Again and again, I find it is the adults - the educators, musicians, and administrators - who predict issues that seem to evaporate on contact, who interpret results so differently from us (Is a smile not a smile? Is a melody not a melody?), who insist on the impossibility of methods that prove to work pretty much the same everywhere. Perhaps what we are seeing is that cultural differences work their magic over time: that elementary- and middle-school-age children are more open to different ways of thinking and learning than their older compatriots. And very likely we are also gathering evidence of how little we understand about that smile and that melody, both we of the Philharmonic and the adults with whom we work.

Theodore Wiprud

Director of Education, New York Philharmonic

************************************************************************************************************

Theodore Wiprud has directed the Education Department of the New York Philharmonic since October 2004. The Philharmonic's education programs include the historic Young People's Concerts, the new Very Young People's Concerts, one of the largest in-school program of any US orchestra, adult education programs, and many special projects.

Mr. Wiprud has also created innovative programs as director of education and community engagement at the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra; served as associate director of The Commission Project, and assisted the Orchestra of St. Luke's on its education programs. He has worked as a teaching artist and resident composer in a number of New York City schools. From 1990 to 1997, Mr. Wiprud directed national grantmaking programs at Meet The Composer. During the 1980's, he taught and directed the music department at Walnut Hill School, a pre-professional arts boarding school near Boston.

Mr. Wiprud is also known as a composer and an innovative concert producer, until recently programming a variety of chamber series for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. His own music for orchestra, chamber ensembles, and voice is published by Allemar Music.

Mr. Wiprud earned his A.B. in Biochemistry at Harvard, and his M.Mus. in Theory and Composition at Boston University, and studied at Cambridge University as a Visiting Scholar.

September 2008

I thought a lot about all those years I had regularly read his column in The New York Times. All those years I watched him on Nightline, and countless other news programs. And of course, it got me to thinking, and thinking hard about how fortunate we are indeed, that he had staked out his claim as a leader in arts education when he became Board Chair of The Dana Foundation.

I knew the Foundation just a little bit before Bill Safire became chair. It had done great work, but nothing to speak of in arts education. I had heard about Safire becoming chair, and then I recall learning from my friend Jane Polin that Dana was going to take up arts education. I asked Jane how that came to pass? I remember her saying that it was Bill Safire's doing, and she just smiled. I had long thought that the key to equitable access to quality arts learning for all children would come from bridges built to those outside the field as traditionally defined. Bill Safire and arts education? Well, how about that!

There are, of course, a lot of foundations supporting arts education. Not enough, mind you, but still, a fair number across the country. It says a lot that under Safire's leadership, and by extension his empowering of people like Barbara Rich and Janet Eilber, that the Foundation was not only to undertake unique work, as in the case of brain research and arts education, but work that is sorely needed and of the very highest quality. While some may think that approach is the norm, believe me, unique, needed, and quality, are not always things that go hand-in-hand in philanthropy.

I heard Safire speak at two different Dana Foundation conferences, and had the chance to talk with him a little bit, just to thank him. It was my brief moment of fandom. Did I get his autograph? I got the impression that he would have shooed me away had I asked. Looking back on that moment, I should have asked.

He spoke matter-of-factly about the importance of arts education and his personal interest in Dana's approach to this issue as a foundation. At the most recent conference last spring on Arts Education and Neuroscience, he was clearly more interested in hearing from the scientists than he was in trumpeting himself or the Foundation.

Beyond its groundbreaking work in arts education and brain research, The Dana Foundation has helped advance the field of teaching artistry, in particular through the funding of work that is enhancing quality, developing deeper practice, and building community. It strikes me that their approach to this work is from a practitioner's perspective.

A change in leadership at any organization is always a cause for concern. I hope that everyone will take the time to write to The Dana Foundation, to thank them for their work, and to strongly encourage them to continue the legacy in arts education established so beautifully by Bill Safire.

For those of you who wonder whether such a thing is appropriate, go ahead and drop whatever issue of propriety you might be mulling over, and just do it!

So, what was I really feeling when I heard that Safire had died, just as I had experienced with the similarly sudden passing of Carlin? I felt that I knew them, that they had a place in my life. I also wondered, who would teach us? In the case of Carlin, who would tell us how idiotic we were?

With Safire, it's very much the same, except his touch, quite a bit kinder, ultimately displayed the touch of a teacher. I tend to think of him as an everyday intellectual or perhaps better put, an everyman intellectual. Perhaps this is why he was such a fine advocate for arts education.

What could be better than to leave this entry with an excerpt from the Chairman's Letter from The Dana Foundation's 2008 Annual Report:

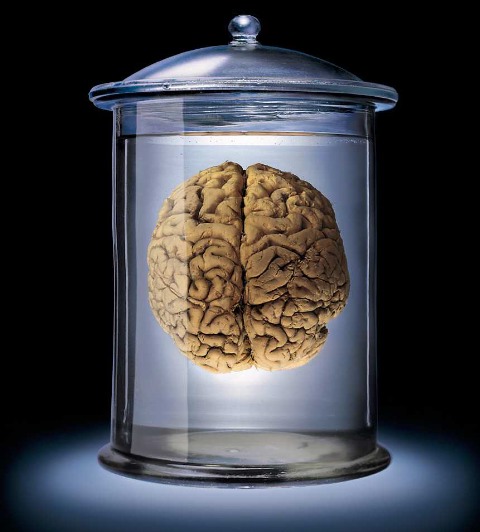

Learning, Arts, and the Brain

Since the industrialist and legislator Charles A. Dana launched his foundation nearly sixty years ago, education has been an active area of its support. At first, construction of auditoriums at colleges was our primary contribution. This was followed by grants from providing fellowships and scholarships to helping disadvantaged students meet the daunting challenge of college calculus. In the past eight years, we have focused on a field of great need: the revitalization of the teaching of the performing arts in our public schools. Whenever local school budgets tighten--in good times and in today's harder times--one of the first activities to be curtailed has been children's education in music, dance, and drama. That's a big mistake, not just because study of the arts attracts young people to remain in school, and not just because an appreciation of our cultural heritage enriches their lives during and long after school. We see other reasons as well: arts study encourages creativity, the precursor to economic productivity; it stimulates the imagination, opening new vistas for scholastic achievement and interesting careers.

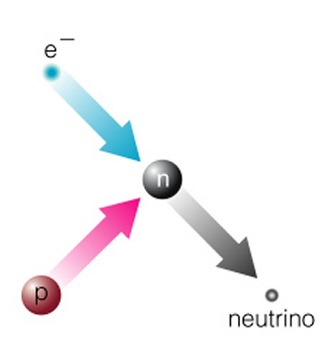

Five years ago, a light bulb went on in our heads: Since we were so deeply involved in spreading the gospel of brain science, might there not be a way to determine whether there is a connection between the study of the arts and the development of the brain's ability to learn? To perceive through the senses, to store memory in areas like the hippocampus, to quickly retrieve that information through the neural circuits--aren't those arts-related functions of the organ inside the skull? And could it be shown that the study of the arts has a direct effect on the ability to concentrate, to focus, so as more easily to learn math, science, and the humanities?

Wishful thinking, said skeptics who preferred more easily measureable academic subjects. Art for art's sake, said some purist critics who disdained any "practical" benefit from studying and performing in their fields. And yet some cognitive neuroscientists, newly equipped with technology to see what was going on in the living and learning human brain, wondered: Why did so many musicians excel at math? Why did children who eagerly performed dance and welcomed its difficult training shine in the seemingly unrelated world of spatial relationships? Why did so many actors have such good memories?

Under the guiding hand of "the father of cognitive neuroscience", Michael Gazzaniga, Ph.D., of the University of California, Santa Barbara, Dana put up $2 million to undertake a three-year study, drawing on the top cognitive talent in the faculties of seven leading universities taking a serious look at the subject so central to cognition and to early education. Their March 2008 report, titled "Learning, Arts, and the Brain" (available in full on our Web site, along with media commentary), was careful not to use the word "causation"--not enough evidence yet to make such a sweeping claim--but found "tight correlation" between facility in an art form and achievement in other domains. "In children, there appear to be specific links between the practice of music and skills in geometrical representation," and in grown-ups, "Adult self-reported interest in aesthetics is related to a temperamental factor of openness, which in turn is influenced by dopamine-related genes." The scientists of the Dana Consortium on Arts and Cognition concluded: "An interest in a performing art leads to a high state of motivation that produces the sustained attention necessary to improve performance and the training of attention that leads to improvement in other domains of cognition."

In June 2008, Dana awarded a grant to a member of the consortium, Harvard's Elizabeth Spelke, Ph.D., to follow up the music-geometry connection with a larger sample, and to investigate whether a musical tone is represented as space in the brain.

Throughout our study and its aftermath, we were hopeful that other educators and neuroscientists would join us in moving this important field of study ahead. Sure enough, in the fall of 2008 the Johns Hopkins University School of Education asked us to join its Neuro-Education Initiative to plan a conference on "Learning, Arts and the Brain." That was the title of the Dana Consortium's report; in a fair exchange, we plan to adopt the Hopkins use of the neologism neuro-education. (An aside: As a combining prefix, neuro- is hot, now including neuro-economics; I thought I had coined the term neuroethics in 2001, but it turns out that the Harvard Medical School psychiatrist Dr. Anneliese Pontius used it in a published paper on child-rearing in 1993. Ah, well.)

The Hopkins gathering is now set for May 6, 2009, at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore. Its purpose, in their words, is "to discuss what is known about arts and cognition, explore research priorities and opportunities, and develop methods of effective communication of findings to educators and stakeholders." Guy McKhann, M.D., professor of neurology and neuroscience at Hopkins and Dana's senior scientific consultant, and I will be among the speakers, along with Dr. Spelke and two other members of our original Consortium: Michael Posner, Ph.D., of the University of Oregon and Brian Wandell, Ph.D., of Stanford. Dana support in addition to Dr. McKhann will include Barbara Rich, Ed.D., head of our News and Internet Office, and Janet Eilber, our director of Arts Education. Dana Press reporters directed by Jane Nevins and Nicky Penttila will cover the proceedings on our Website and in our publications Brainwork, Brain in the News, and Arts Education in the News.

The next day, in nearby Washington D.C., a "Learning, Arts, and the Brain Summit and Roundtable" will take place, part of a two-day Learning & the Brain conference. For the past five years, we have worked with the dedicated educators of Learning & the Brain on these semi-annual gatherings, which often draw up to 1,000 teachers, administrators and scientists; Dana Alliance members, and Dana staff and consultants often participate in their panels.

There's nothing like a group of fired up, crazy-passionate moms to get something done, and when it comes to our kids' education in particular, there's no shortage of work to be done. Mom Congress, a Parenting initiative with Georgetown University -- our education provider -- is here to help you make the changes you want in your local schools, and for kids nationwide.Well, this month the Mom Congress takes a look at K-12 Arts Education in an article titled Why Art Makes Kids Smarter, by Nancy Kalish.

They also have put together four organization links they are calling their Arts in Action Toolkit.

"...Gonzalez (MS 223 principal) goes against current practice and eliminates periods of math, English language arts, and other subjects on a rotating basis to make room for 12-week blocks of visual arts, drama, dance, and both instrumental and digital music. "The academics haven't suffered," says Gonzalez. "Instead, the whole school has improved."

I love this entry. Can an ordinary 10-year-old compose music? Read on! RK

***********************************************************************************************************

10.11.09

Yesterday, the New York Philharmonic premiered eight new pieces in one concert at Suntory Hall. As though that's not news enough, the pieces were composed by ten- and eleven-year-old Tokyo schoolchildren: not prodigies, just ordinary kids with some imagination and a willingness to work hard. Musicians, audience, conductor - everyone was astonished and delighted.

These pieces go way beyond cute - in fact, the "c" word is a slur to Jon Deak, the composer and Philharmonic bassist who created Very Young Composers. VYC is a radical approach to working with kids that enables just about anyone to compose music for orchestra. These eight pieces have depth; they are authentic to eight different kids' imaginations and lives; and as Magnus Lindberg, the Philharmonic's composer-in-residence said, they are all exactly the right length: their two-minute forms are exactly right to their contents - something professional composers often struggle to attain.

The suite of new works by Very Young Composers of Tokyo was intended as something of a provocation, demonstrating in this most rule-bound, sensei-respecting society that adults have much to learn from the imaginations of children. Very Young Composers is the most extreme student-centered learning imaginable. The music all comes from the children, who as composers become senseis to this great orchestra and its music director. The process does not so much teach them to compose, as to discover their own potential. The thrill of hearing their ideas come to life, through diligent work, creates in each child a need, a hunger for musical technique so that the can take the next steps themselves. It is still early in this venture, which Jon Deak began in the US ten years ago by asking the innocent question, what is children's music? We don't know how many of the 500+ kids who have composed for the Philharmonic will become composers or musicians or brain surgeons. But it will be interesting to find out.

One of the most interesting things about VYC in Japan has been the difficult position it creates for the child composers themselves.

First, their parents signed them up a year ago in a time-honored drive to provide the best opportunities for their children. We started with eight, expecting some to drop out. None did. Credit the mothers, because it turns out that being singled out is not a good thing in a Japanese school or social set. Children here are teased and bullied not for being nerds but for being different in any way. So when the Teaching Artists Ensemble played six of these pieces at Nanzan Elementary School with those six composers in the audience, their names could not be mentioned, and the composers made themselves very small as their pieces were played. In some settings, the kids and the school prefer us to talk about the pieces as a group project - whereas in reality, the eight children all composed their pieces individually in their entirety, including harmony and form, most of them playing them on piano or another instrument for transcription by our Teaching Artists.

The kids' ambivalence about taking credit has fed suspicions among Japanese musicians that the children could not have composed these pieces themselves. We have heard for a year about Japanese kids not being creative because of the culture they grow up in. It's been suggested that Japanese kids just say "yes" to every option presented to them - but if that were our method, we would finish these pieces in an afternoon, not in a ten-month process. The fact is, these eight kids were as creative, as free, as confident in using the big sound of the orchestra, as any of the kids in New York have been. It's been a fascinating experiment and the results are as clear as day.

I have no way of predicting what impact the VYC Provocation will have on Japanese musicians, schools, or society. Ten years of VYC premieres in New York are just beginning to infiltrate people's thinking about children and creativity, and changing Japanese ways of thinking is not the mission of the New York Philharmonic. But those who hear these pieces glimpse as if through a window that opens for two minutes at a time the depth of a child's mind and the limitless possibility of enlightened, Socratic mentoring. As well, one gets a thrilling sense of the future of music, if even a few kids go on to explore these sounds and forms as professionals.

Very Young Composers of Tokyo at work with New York Philharmonic Teaching Artists David Wallace and Richard Carrick

N.B., Photos of the Young People's Concert with the Very Young Composers of Tokyo will soon be up at nyphil.org - click on the Virtual Tour link

***********************************************************************************************************

Theodore Wiprud

Director of Education, New York Philharmonic

Theodore Wiprud has directed the Education Department of the New York Philharmonic since October 2004. The Philharmonic's education programs include the historic Young People's Concerts, the new Very Young People's Concerts, one of the largest in-school program of any US orchestra, adult education programs, and many special projects.

Mr. Wiprud has also created innovative programs as director of education and community engagement at the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra; served as associate director of The Commission Project, and assisted the Orchestra of St. Luke's on its education programs. He has worked as a teaching artist and resident composer in a number of New York City schools. From 1990 to 1997, Mr. Wiprud directed national grantmaking programs at Meet The Composer. During the 1980's, he taught and directed the music department at Walnut Hill School, a pre-professional arts boarding school near Boston.

Mr. Wiprud is also known as a composer and an innovative concert producer, until recently programming a variety of chamber series for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. His own music for orchestra, chamber ensembles, and voice is published by Allemar Music.

Mr. Wiprud earned his A.B. in Biochemistry at Harvard, and his M.Mus. in Theory and Composition at Boston University, and studied at Cambridge University as a Visiting Scholar.

September 2008

************************************************************************************************************

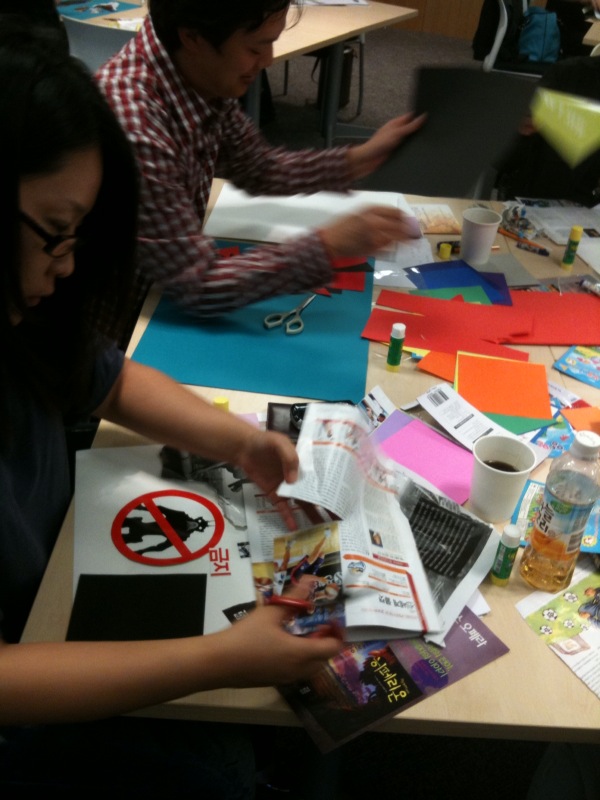

Dewey 21C 10.8.09

Korea, land of Teaching Artists! Seriously: the South Korean government launched a new agency - Korea Arts and Cultural Education Service, or KACES - three years ago with a mandate to increase economic output by strengthening creativity among Korean youth and adults. KACES has ramped up incredibly fast, now fielding 3,500 Teaching Artists - yes, three thousand, five hundred Teaching Artists - in a dozen different disciplines, from Western and Korean classical musics to writing to animation. They are working in over 50% of schools in the nation. Plus social service centers, homes for the elderly, hospitals, refugee centers, and prisons. They are adding three more disciplines next March. This is an agency with huge ambition and in my experience, dedicated, visionary, highly professional staff.

A government mandate complete with an agency - quite the opposite of the US approach to arts education, Teaching Artistry in particular, based on insurgency from parents, artists, and cultural organizations.

For three days, New York Philharmonic Teaching Artists David Wallace and Jihea Hong Park (no harm bringing a TA who speaks the language) and I did workshops and performances for Korean musicians, educators, Teaching Artists, arts administrators, and even some kids and parents. What did we find out?

KACES TA Hyun Ju Choi described her process of teaching kids traditional Korean drumming. No rote learning of ancient tradition here. Students make up words to traditional rhythms and play games with traditional singing styles (we as an audience caught on pretty fast and had fun in the process). Ms. Choi's approach is strikingly student-centered, and the result so far is a group of kids who performed for us with great enjoyment in their music-making. If they are not yet playing with the greatest precision, they are taking on old traditions that had fallen out of fashion with the arrival of Western classical music, and they have their whole lives ahead should they want to become traditional musicians.

This impression only confirmed what we were finding all along - that somehow, the experiential approach to learning that's at the heart of progressive Western thought has a large following in Korea. When we did an involved aesthetic education workshop for KACES music TAs and administrators, they were put off by our non-musical first half. (We started with a visual arts workshop, taking them out of their musical comfort zone just as we do with Philharmonic TAs.) But when we moved into musical territory, inviting them to create variations on a John Dowland song as preparation for hearing Benjamin Britten's Lachrymae, they were thrilled, and I think in the end they saw how the visual art workshop had been a set-up for the set-up. We have lots of new correspondents eager to find how to learn these techniques.

That's partly because training is a big challenge when dealing with so vast a system. Right now each TA gets 20 hours of training per year, in one shot, and then is pretty much on his or her own. The Philharmonic luxury of monthly trainings and semi-annual retreats staggered them. Sure enough, this is a priority area KACES is working on. But mandates for growth and for reaching more constituencies is a given with government, and the arts education professionals are struggling to keep up.

Still, when KACES does catch up with itself - with a clearer philosophy rooted in Korean needs and resources rather than on international models; with a clearer profile to its style of teaching; with a system of recruiting and training Teaching Artists to match its ambitions - Korea will be the Venezuela and KACES will be the El Sistema of Teaching Artistry. And what might the US become, if we can learn to go to scale anything like the way they have? Imagine 50% of US schools partnering with Teaching Artists! The early chapters of Teaching Artistry, the incubation and experimentation and definition, may be drawing to a close in ways we never imagined.

A final note for today: when David and Jihea engaged an audience of children, parents, and teachers in Incheon with their brilliant concert leading to authentic, personal appreciation of Britten's Lachrymae, the most avid participants were the adults. I find a very appealing openness in many Koreans, and a direct honesty in their response. Arts leaders in Korea are thinking of Teaching Artistry in a broad way, for audience development as much as community engagement. This may prove another area where we are soon importing Korean strategies.

Korean Teaching Artists in an aesthetic education

workshop

Korean Teaching Artists in an aesthetic education

workshop

Gallery of Teaching Artists' collages expressing reactions to injustice or pain - preparation for engaging with Benjamin Britten's mediations on a Dowland song on the same subject

David Wallace improvising variations on the Dowland song devised on the spot by

children in Incheon

Theodore Wiprud

Director of Education, New York Philharmonic

Theodore Wiprud has directed the Education Department of the New York Philharmonic since October 2004. The Philharmonic's education programs include the historic Young People's Concerts, the new Very Young People's Concerts, one of the largest in-school program of any US orchestra, adult education programs, and many special projects.

Mr. Wiprud has also created innovative programs as director of education and community engagement at the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra; served as associate director of The Commission Project, and assisted the Orchestra of St. Luke's on its education programs. He has worked as a teaching artist and resident composer in a number of New York City schools. From 1990 to 1997, Mr. Wiprud directed national grantmaking programs at Meet The Composer. During the 1980's, he taught and directed the music department at Walnut Hill School, a pre-professional arts boarding school near Boston.

Mr. Wiprud is also known as a composer and an innovative concert producer, until recently programming a variety of chamber series for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. His own music for orchestra, chamber ensembles, and voice is published by Allemar Music.

Mr. Wiprud earned his A.B. in Biochemistry at Harvard, and his M.Mus. in Theory and Composition at Boston University, and studied at Cambridge University as a Visiting Scholar.

September 2008

Some will find ways to establish a network of new schools or develop models that turn around low performing schools. Others will find new ways to use technology. Others might explore how to engage children in the arts to help them improve. We want the best ideas to move us forward. We will be investing in great work to scale up existing programs that have already shown success, can validate ones that need to establish evidence of their success or to develop new ideas to determine their potential.Click here to go directly to the announcement., including fact sheets, Powerpoint presentations, transcript of presentation, and more.

Individual school districts or groups of districts can apply for the i3 grants, and entrepreneurial nonprofits can join with school districts to submit applications. Colleges and universities, companies and other stakeholders can be supporters of the projects.

Applicants must demonstrate their previous success in closing achievement gaps, improving student progress toward proficiency, increasing graduation rates, or recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers and principals.

Grant recipients will be required to match federal funds with public or private dollars (20% matching requirement. Successful applicants will need to demonstrate how their programs will be sustainable after their federal grants are completed.Under the proposed priorities, grants would be awarded in three categories:

- Scale-up Grants: The largest possible grant category is focused on programs and practices with the potential to reach hundreds of thousands of students. Applicants must have a strong base of evidence that their program has had a significant effect on improving student achievement.

- Validation Grants: Existing, promising programs that have good evidence of their impact and are ready to improve their evidence base while expanding in their own and other communities.

- Development Grants: The smallest grant level designed to support new and high-potential practices whose impact should be studied further.

As in Race to the Top, there will be a 30 day period for collecting public comments prior to the release of the final guidelines.

I believe that this will be the single most competitive grant program in the history of the United States. That's right, no hyperbole. Think about it, even if only a subset of school districts are eligible, you have thousands of school districts (local education agencies), thousands of non profits when you include all the charter operators, higher education, etc. Grants will be at either the $5mm level for "development," $30 mm for "validation," or $50 mm for "scale-up."

While the matching requirements will reduce the field of applicants significantly, you're still looking at something quite fantastic.

More to follow.

It is understandable. If someone is only going to post once or rarely, that is certainly the usual starting point. Let's call it the arts education cheerleader blog. Give me an A; give me an R; give me a T....

Reading these blogs got me to thinking. What if few of these rationales proved to be true? What if we had no wagon to hitch to, such as 21st Century Skills, or improved SAT scores, or increased motivation?? What if it most of it proved to be illusory?

What if all we had was limited to something that didn't improve graduation rates, and excluded things that are not extrapolations of one sort or another?

In a field that is still looking for that silver bullet of research, proving some sort of transference that will establish arts education as a central part of K-12 education forever, what would happen if most of the things we hitch our wagon to or posit were untrue?

I guess you could say that this might just be the back-to-basics question for K-12 arts education. What do we know to be true and universal? What do we think? What do we hope? What do we know to be specious?

I will probably receive some off-line emails saying that these are very good questions indeed, but shouldn't just leave it at that. They will tell me to go ahead and answer the questions.

Sorry. I prefer to leave it all as a good set of questions for a sunny early October morning.

Maybe you might like to take a stab at an answer...

I have to say, I love this stream of pieces that is being generated by Dana. This piece, What Dance Can Teach Us About Learning? "highlights the importance of including physical learning in the classroom, to stimulate creativity, increase motivation and bolster social intelligence."

The AON experiments provide glimpses into a brain system that is exquisitely tuned to learn and to understand physical knowledge. Such insights from cognitive neuroscience help to identify learning principles important to education policy and practices; they form the very basis of the new (and growing) academic field of neuroeducation. Our society places great emphasis on academic success within a narrow set of areas (math, reading or higher IQ). This makes it tempting to apply a narrow translational framework whereby the value of dance, music and other physical arts depends only on the degree to which these pursuits make a student more successful in the desirable academic areas.

As a follow-up to Jane Remer's finely-honed blog on Dewey21c (Arts Advocacy is a Double-Edged Sword), I thought it might be helpful to post a bit of a rundown on the various types of advocacy. While the term "advocacy" may be bounced around in a singular manner, it is after all an umbrella term describing many different types of activities.

As a follow-up to Jane Remer's finely-honed blog on Dewey21c (Arts Advocacy is a Double-Edged Sword), I thought it might be helpful to post a bit of a rundown on the various types of advocacy. While the term "advocacy" may be bounced around in a singular manner, it is after all an umbrella term describing many different types of activities. Before I get to that, I do think it's important to note that the nature of arts education advocacy is changing rapidly. If you look at the work of Arts for All in Los Angeles, you're going to see some very interesting and hopefully promising organizing and training activities. Big Thought is also engaging a broad community is new ways. My own organization, The Center for Arts Education, has quite a bit going on in this arena, including parent training, campaigns, coalition-building, legislative advocacy, and more.

I would argue that arts education "advocacy" has been slow to develop, and that most of it is in the category of random acts of advocacy (as exemplified by arts lobby days on the hill and with state and local governments). It has tended to be more about a budget line to an individual organization than actual policy or constituency building. While this is a bit less the case on the federal level, it's certainly true on the local level. Don't they say that all politics is local?

Yes, the issue of message is still a tough one, as Jane points out so very, very well. However, the making of common cause with those not directly from the arts education field is really starting to move forward.

Here is a nice representation of the various types of advocacy, thanks to the W. K. Kellogg Foundation:

Types of Advocacy Including Lobbying

Types of Advocacy Including Lobbying

Advocacy

Advocacy encompasses a broad range of

activities that involve identifying, embracing, and promoting a cause.

It is an effort to shape public perception to effect change that may or

may not require changes in the law. Advocacy is about using effective

tools to create social change. Lobbying is only one of these activities.

The following activities do not involve lobbying:

• Public Education

A

nonprofit develops a public information campaign to raise awareness of

the rise in childhood obesity. In this campaign they recommend a

variety of approaches to reverse this trend.

• Issue Research

A nonprofit regularly creates

and distributes briefs describing policy barriers to improving

end-of-life care to its state's legislative committees on health,

insurance, and aging.

• Policy Education

At the request of a

congressional committee investigating how to move children out of

foster care into adoptive families more quickly, several nonprofit

organizations from various states describe their innovative foster care

reform models to help policymakers make a more informed decision as

they grapple with policy decisions on this topic.

• Voter and Candidate Education

A nonprofit

sends a questionnaire about their priority issue to all the mayoral

candidates in a local election and published the received responses

(unedited) in their newsletter or the local paper.

• Organizing and Mobilizing

A grantee nonprofit

organized a series of community meetings, public hearings, interviews

with target group members, scientific surveys, and events that drew

hundreds of child welfare system stakeholders together over a period of

months to "vision" a comprehensive strategy to reform child welfare

system policies and practices in its state.

• Judicial Advocacy

The NAACP files a class action suit to compel a state to integrate public schools.

• Executive (Administrative) Advocacy

A

nonprofit representing patients and loved ones struggling with

Alzheimer's disease consulted with state health department officials to

help rewrite eligibility rules to ensure better access to subsidized

assisted living facilities. Legislation is not discussed.

A nonprofit promoting school-based health centers met with representatives from its state's Medicaid office to recommend an innovative way to structure a Medicaid waiver that will increase funding to all centers in its state.

A nonprofit urges the general public to send comments to the Department of Health and Human Services on a proposed federal rulemaking that is open for public comment.

When these kinds of advocacy (above) take positions on specific pieces of legislation, particularly pending legislation, they become lobbying. For example, if the Alzheimer's association mentioned immediately above, took a position on pending legislation and asked for health department officials' support for their position, they would be lobbying.

Lobbying

Definitions

- "Lobbying" is virtually any advocacy activity aimed at influencing a "legislator's" vote on specific legislation.

- "Legislator" refers to

--Members of Congress or their staff

--State legislators or their staff

--Local legislative representatives (e.g., on county boards and city councils)

--The public, in case of a ballot measure

--Members of an organization (if asked to take action on legislation) - "Legislation" is defined as action by a legislative body including the introduction, amendment, enactment, defeat or repeal of Acts, bills, resolutions, appropriations, and budgets. Also included are the U.S. Senate confirmations of executive and judicial branch nominees and proposed treaties that need U.S. Senate approval.

Direct Lobbying

Direct lobbying occurs when a

nonprofit organization attempts to influence specific legislation by

stating a position to a "legislator" or other government employee who

participates in the formulation of legislation.

- Leaders from a nonprofit offer unsolicited testimony before the

local city council meeting just before it was to vote on a proposed ban

on soda in school vending machines.

- A nonprofit sends a letter to the chair of the appropriation

committee opposing certain budget cuts and proposing other budget

increases.

- There are four statutory exceptions:

Nonpartisan analysis, study or research - may have a point of view but must provide a full and fair exposition of the underlying facts to enable reader to form an independent opinion or conclusion on the subject and be widely disseminated and not limited to people on one side of an issue.

Request for technical advice or assistance - a written request from a legislative body that is available to all members of the requesting body.

Self-defense - communication on an action which could impact an organization's existence, powers, duties, tax-exempt status or the deductibility of contributions to the organization.

Discussion of broad, social, economic, and similar problems - discussion on general topics which may be the subject of specific legislation but must not refer to specific legislation or directly encourage action.

Grass Roots Lobbying

Grass roots lobbying occurs when a nonprofit organization urges the general public to take action on specific legislation.

For example, MADD organizes a massive "call or write your governor and senate president campaign" to urge toughening a state drunk-driving law.

Key indicators of Grass Roots Lobbying:

- Relates to specific legislation

- Reflects a point of view on the legislation's merits

- Encourages the general public to contact legislators

Lobbying is Legal and Important

The term "lobbying" carries negative connotations for many people because it may raise the specter of violating federal law and losing tax-exempt status, or because it is often associated with scandals involving paid lobbyists representing corporate interests. Nonetheless, lobbying by nonprofit organizations exempt under 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Code is a legal and acceptable activity that is often essential to creating good public policy and stronger, more democratic communities.

*************************************************************************************************************

As I have said for years, the arts education community is not a true "field," as it is riddled with great diversity of philosophy, purpose, method, content and ways of accountability. Arguing or advocating for financial and other support can be a tricky business because different "camps" make different claims, and it is often difficult to know what "outcomes" arts groups are campaigning for. As I see it, there are three major (often overlapping) positions when it comes to persuading, begging and bragging for financial support and recognition:

• The Human Intelligence and Development approach - Teaching and Learning, "we believe the arts are essential to every child's cognitive, affective, social and physical growth and belong in the core of the curriculum alongside math, literacy, science, and social studies," folk,

• The Moral Imperative approach - Enrichment and Exposure, "we believe every child deserves regular exposure to all the arts to enrich the quality of their lives and the culture of their communities, ... and to build future audiences," folk, and

• The Utilitarian Cake and Eat It approach - "Arts Integration, "we believe the arts are important vehicles and provide pathways for learning other subjects, skills, and concepts and should be woven into the curriculum to help teach math, literature, science, etc. folk. (Note: this definition is often tempered in writing with the caveat that the art form will receive equal treatment and attention, but in classroom actuality, time runs out and the study, skills and understanding of the art forms are more often than not forgotten or neglected.)

We may argue that these three "camps" are best seen as slices of a pie, or perhaps a Venn Diagram in which the four major art forms and some of the learning and other outcomes are the constants; everything else hugs to its "camp," but I fear that picture is too simplistic. The possible variations of slicing and dicing are almost endless, and do not address or help solve the advocacy conundrum.

The issues are (1) whether there is or ought to be a consistent platform or position that would satisfy all camps and at the same time make a powerful argument for supporting the arts as education, and (2) which arguments are the most powerful. And the answer is, as always, it depends. If you are arguing for the arts as education of the human intelligence and development, your pitch is often about teaching and learning; the moral imperative tends to appeal strongly to the ethically and artistically inclined and weaker with the accountability crew, the policy makers and bottom line business people. The utilitarian approach appeals to all Americans who recognize the arts connection to other subjects as a pragmatic wedge in the schoolhouse door and a fair compromise between the teaching and learning and moral imperative approaches. Given the diversity of our community, I doubt there is a platform or set of arguments that would satisfy "the field." Moving on, then, to issues around which we can perhaps coalesce.

What has always and still troubles me is that the arts community that makes such a significant and relatively expensive contribution to the education community is its own and almost only champion. We still haven't figured out how to make aggressive allies and stalwart champions out of a critical mass of the schools and educators who are our regular partners or to whom we provide services. We have not learned how to convey the enormity of the contribution we make to teaching and learning, to the human psyche and ethical senses, or to the connection and illumination of other subjects and disciplines.

We tend to use apologetic phrases such as "we work with the willing" and "pockets of excellence" when defending our relatively small impact on general education. Things haven't really changed that much since the sixties when we started our brands of arts education except that back then we really did have vibrant allies and champions in the U.S. Office of Education and the national elementary and secondary educational community, and the Humanities Endowment, to mention only a few. I attribute that support largely to the fact that we were part of a compensatory educational push in a broad social agenda for a Great Society which these days, the Obama administration only vaguely touches on.

We tend to settle for crumbs and call it progress, or leverage. We celebrate a token arts education "month" (just like a token Black History month), we make all the noise we can to draw attention to our work (successfully, but at best for a New York minute). We storm federal, state and local legislators' offices with boasts and brags about isolated arts "services" and activities that in no way transmit the context, breadth and depth of our most serious, imaginative and even "scholarly" work, the idea of commitment over time, and stories of powerful instructional and collegial relationships built between classroom teachers, arts specialists and professional artists in their extended work with students and their parents.

As I wrote at length in Beyond Enrichment over a decade ago, it strikes me as foolhardy to claim and bray about a kaleidoscope of often unrelated activities that will simply serve to underscore and perpetuate our reputation of superficial, even trivial entertainers "so nice to have, but not necessary." When we provide no indication of on-going planning, professional development, teaching and learning and sustained assessment, the seriousness of some of the arts providers work is lost in the carnival-like atmosphere.

Arts education deserves better advocacy than that. If we keep missing the boats that broadcast how hard we work as respectful, humble and committed partners to teach for deep understanding and extended learning in and through the arts, not isolated activities taught by those who come and go making no permanent dent in the school culture, we have only ourselves to blame if we are ultimately ignored both by the schools and the policy makers. Let us get together to turn our swords into plowshares.

Jane Remer October 1, 2009

************************************************************************************************************

JANE REMER'S CLIFFNOTES We are at another rocky precipice in our history that threatens the survival of the arts in our social fabric and our school systems. The timing and magnitude of the challenges have prompted me to speak out about some of the most persistent issues in the arts education field during the last forty-plus years. My credo is simple: The arts are a moral imperative. They are fundamental to the cognitive, affective, physical, and intellectual development of all our children and youth. They belong on a par with the 3 R's, science, and social studies in all of our elementary and secondary schools. These schools will grow to treasure good quality instruction that develops curious, informed, resilient young citizens to participate fully in a democratic society that is in constant flux. I have chosen the title Cliff Notes for this forum. It serves as metaphor and double entendre: first, as short takes on long-standing and complicated issues, and second, as a verbal image of the perpetually perilous state of the arts as an essential part of general public education. I plan to focus on possible solutions and hope to stimulate thoughtful dialogue on-line or locally.

************************************************************************************************************

Jane

Remer has worked nationally for over forty years as an author,

educator, researcher, foundation director and consultant. She was an

Associate Director of the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund's Arts in

Education Program and has taught at Teachers College, Columbia

University and New York University. Ms. Remer works directly in and

with the public schools and cultural organizations, spending

significant time on curriculum, instruction and collaborative action

research with administrators, teachers , students and artists. She

directs the Capezio/Ballet Makers Dance Foundation, and her

publications include Changing Schools Through the Arts and Beyond

Enrichment: Building Arts Partnerships with Schools and Your Community.

She is currently writing Beyond Survival: Reflections On The Challenge

to the Arts As General Education. A graduate of Oberlin College, she

attended Yale Law School and earned a masters in education from Yale

Graduate School.

Jane

Remer has worked nationally for over forty years as an author,

educator, researcher, foundation director and consultant. She was an

Associate Director of the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund's Arts in

Education Program and has taught at Teachers College, Columbia

University and New York University. Ms. Remer works directly in and

with the public schools and cultural organizations, spending

significant time on curriculum, instruction and collaborative action

research with administrators, teachers , students and artists. She

directs the Capezio/Ballet Makers Dance Foundation, and her

publications include Changing Schools Through the Arts and Beyond

Enrichment: Building Arts Partnerships with Schools and Your Community.

She is currently writing Beyond Survival: Reflections On The Challenge

to the Arts As General Education. A graduate of Oberlin College, she

attended Yale Law School and earned a masters in education from Yale

Graduate School.*************************************************************************************************************

Within the Western educational system, the Teaching Artist attempts the most complete realization of student-centered learning. To borrow from Eric Booth, the word "education" has the Latin root "ducare" - to lead or draw, with the prefix "e-", out. The fundamental stance of the Teaching Artist is that every learner has inherent capacities that can be brought out by encounters with art. The encounter evokes a desire to know more, experience more, create more, that ignites learning.

If this is a difficult ideal to project in the United States, where high-stakes testing usurps more and more of the school day and teachers' attention, imagine trying to communicate the concept of "e-ducare" to exam-centric Asian systems. For over a millennium, students' futures in China, Japan, and Korea have hinged on their performance on state exams. The exam system reinforces a cultural reverence for the elder, the teacher, who provides all the knowledge a student needs to progress through the exams and on to a career. When Western classical music, with its emphasis on precise performance of detailed tasks, came to the Far East, it flourished in the exam system. Japanese and Korean musicians have already been renowned for several generations. Now China is training literally millions of violinists to very high standards. Many of the most recent hires at the New York Philharmonic - including the crucial principal oboe - have been born and trained in China. Why should Asian conservatories begin now to develop musicians' engagement skills?

Teaching Artists of the New York Philharmonic have just completed a week of projects in three locations in Japan. Although this is the fourth year of such work, we continue to be struck by how different responses can be from those we encounter in New York - and how much the same. In Niigata, as I described in the last post, we found a university education faculty looking for new ways to tap children's creativity as a learning tool. Students, in uniforms, were highly ordered as the marched into the gym for our interactive concert - which could be a good or a bad sign for engagement. But they came alive in response to the Teaching Artists' enthusiasm and scaffolded presentation of ideas and activities (Junior high students, as in the US, though showing signs of engagement, were reluctant unto death about raising their hands, in contrast to their younger counterparts.) In the Minato ward of Tokyo, we returned to a progressive school called Nanzan Elementary. Here the students were too unfocused to participate fully, and teachers did little to restrain their chatter. The ensemble was playing music by six students at Nanzan - can you imagine how American students would capitalize on the opportunity for attention? Here, we were asked not to announce their names, and even so, the composers cringed, shrank from sight. (Come to think of it, I have had performances, as a composer, that made me feel that way - but I'm sure the performance level was not the issue here!) Nanzan seems to take an almost Western concern for students' feelings, enabling them to opt out of important experiences. Uniform, Japanese education is not.

In Komae, an outlying ward of Tokyo, we presented a highly successful family concert. Children of all ages were much more apt to participate - to sing along when requested, to learn and clap rhythms, to volunteer ideas for composing on the spot, to take a shot at drumming on compound buckets - when with their families, than with their classes. The lesson again: once you let kids know it is OK, indeed encouraged, for them to volunteer thoughts, to try things they haven't yet mastered, they can dive in and have fun pretty much like their Western counterparts.

Arts administrators who attended a seminar we gave on Teaching Artistry yesterday took copious notes and nodded vigorously (a confusing tendency among Japanese, not by any means indicating consent). Those who spoke with me afterward were thrilled by the possibility of making deeper connections with their communities, which seems increasingly to be their mandate. Whether arts presenters will develop an infrastructure for Teaching Artists remains to be seen.

The response of professional musicians, as reported by our partner and host, Kazumichi Sunada of Life With Music Project, tends to be depressingly similar to that in the US: musicians who need to play for kids must not be good enough to play for adults. Any who heard the Teaching Artists Ensemble perform would have been surprised - I know I have never heard a better Brahms Piano Quartet in g minor, and these musicians can improvise, too. Meanwhile, Riichi Uemura and Mizuka Motoki, who joined the ensemble as apprentices, describe a life-altering shift of perspective. Riichi had already given up a life as a professional quartet player in Italy - cushy but disconnected from audiences - to return home and find ways to engage.

Educators in Japan respond that they are too hemmed in by the national curriculum, with its focus on exam preparation, to turn class time over to soft activities that promote different kinds of learning. Perhaps they are right: perhaps putting students in charge of their own learning for even a few class periods could undermine years of acculturation and jeopardize their futures. After all, it's hard to argue with the success of Japanese education, especially coming from the US.

So, while a fringe of Japanese educators and musicians call for change and look to student-centered, arts-inspired models from the United States, the direction of schooling back home is toward a more Asian model of high-stakes testing. As in so many things, Teaching Artistry falls between a number of stools, a fringe activity working toward a shifting center both here and in Asia. Perhaps because it is still relatively new, and because it is so differently practiced in different places, Teaching Artistry remains poorly understood and difficult to convey. Until one has seen an interactive concert by the Teaching Artists Ensemble of the New York Philharmonic, or heard music composed by a ten-year old, one cannot begin to grasp the power of what we are about. When asked to encapsulate what a Teaching Artist is, rather than resort to theories of learning, I have come to use two words: musical activist. That certainly applies to the Teaching Artists on our faculty, who, God help them, actually hope to change the world.

Teaching Artists Ensemble of the New York Philharmonic: Janey Choi, violin;

guest artist Mizuka Motoki, clarinet;

Teaching Artists Ensemble of the New York Philharmonic: Janey Choi, violin;

guest artist Mizuka Motoki, clarinet;  Junior high music students with Philharmonic Teaching Artists, post-concert

Junior high music students with Philharmonic Teaching Artists, post-concert

Junior high students filing in for a Teaching Artists Ensemble concert in

Nagaoka

Junior high students filing in for a Teaching Artists Ensemble concert in

Nagaoka****************************************************************************************************************

Theodore Wiprud

Director of Education, New York Philharmonic

Theodore Wiprud has directed the Education Department of the New York Philharmonic since October 2004. The Philharmonic's education programs include the historic Young People's Concerts, the new Very Young People's Concerts, one of the largest in-school program of any US orchestra, adult education programs, and many special projects.

Mr. Wiprud has also created innovative programs as director of education and community engagement at the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra; served as associate director of The Commission Project, and assisted the Orchestra of St. Luke's on its education programs. He has worked as a teaching artist and resident composer in a number of New York City schools. From 1990 to 1997, Mr. Wiprud directed national grantmaking programs at Meet The Composer. During the 1980's, he taught and directed the music department at Walnut Hill School, a pre-professional arts boarding school near Boston.

Mr. Wiprud is also known as a composer and an innovative concert producer, until recently programming a variety of chamber series for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. His own music for orchestra, chamber ensembles, and voice is published by Allemar Music.

Mr. Wiprud earned his A.B. in Biochemistry at Harvard, and his M.Mus. in Theory and Composition at Boston University, and studied at Cambridge University as a Visiting Scholar.

September 2008

Blogroll

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog