Dewey 21C: August 2009 Archives

This is one very fine read. Plus, it won't take you too long. If you have any interest in reading a piece that dissects a recent positive piece of research on a high profile program training principals in New York City, this what you want to click through to.

More than anything, this gives you a good idea of the gulf between news reporting and analysis. (Wasn't that what got us into the Irag war?)

So, read this first: On GothamSchools.org, Aaron Pallas takes a close look at the recent report by NYU on The Leadership Academy: Bungled by Design. Yes, it is the same link in the first paragraph.

Then this: Ed Week's coverage of the report.

Then this: New York Times coverage of the report.

Then this: New York Post coverage of the report.

Finally, I can't end this post without commenting on the limits of assessing the Aspiring Principals Program primarily on the basis of the state test scores achieved by students (for the elementary/middle schools). The fact that such test scores are often available--although never for students below grade 3!--and are at the center of the city's accountability system does not justify the decision to exclude virtually every other measure of principal performance that might be relevant.

When I think of Ted Kennedy, I think of a line of Democrats that reach way back to FDR. The wealthy elites who are brought up to serve the public and for my money, demonstrate a commitment to a progressive agenda that is centered in social justice. Were they perfect, of course not. From FDR to Teddy Kennedy. Was Teddy the end of the line?

I was watching some of Ted Kennedy's speeches this morning. The one I didn't see was the one I remember most of all: his eulogy of his brother Robert. It was a powerful, iconic moment in American history.

If you look and listen during these days of remembrance and tribute, there is something different in his passion and compassion than you find in almost all of the elected representatives: a light in the eyes, a fierce fight for his agenda and values. There is a song in his voice too, a song that I hadn't heard from anyone else for a long, long time, at least until Barack Obama appeared on the national stage.

Even though they should, many people do not know how how much of NCLB was Teddy Kennedy. When George W. Bush said that he would reach across the aisles to work with the democrats, NCLB was perhaps the most significant evidence of his making good on that pledge.

NCLB is roundly rejected within the arts education community, and in many, many other quarters. What is lost on many of the opponents of NCLB is that it is favored by more people than a group of conservatives. NCLB has had some pretty strong support within low economic urban schools communities, where the local school districts have often failed to provide a sound, basic education. The focus on performance, for many of the parents in these schools, was perhaps the first time in a long time they saw standards and achievement being pushed, measured, and tied to consequences. That focus has meant something to a lot of people.

This is often lost in the din of those who want NCLB ended or significantly overhauled.

Now don't get me wrong: I am not defending NCLB, but rather trying to provide a fair statement as to the side that supports it and why.

While President Obama was highly critical of NCLB on the campaign trail, many people believe that the administration is closely tied to its fundamental premise and will seek to improve it rather shut it down. Politically, that may be a wise move. Without diverting this blog to being about how to improve NCLB, I will simply say for the moment that significantly improving NCLB is much more than tweaking its engine, as there are many, many complicated pieces that would have to be put in place across all fifty states to make a better engine work.

We should get a better sense soon of how this will all shape up.

All of this bring me to a feature on NEA Chair Rocco Landesman in today''s Washington Post:

While I have no bone to pick with the goals of NCLB, which is why I think Teddy Kennedy was so much a part of creating and defending it, it is unquestionably a matter of implementation rather than goals.

That being said, it will be very interesting to see how much leeway Landesman is given to press education policy. Will he be reigned in or be the firebrand? Will he become, in effect, the arts czar that many people lobbied for??

I was watching some of Ted Kennedy's speeches this morning. The one I didn't see was the one I remember most of all: his eulogy of his brother Robert. It was a powerful, iconic moment in American history.

If you look and listen during these days of remembrance and tribute, there is something different in his passion and compassion than you find in almost all of the elected representatives: a light in the eyes, a fierce fight for his agenda and values. There is a song in his voice too, a song that I hadn't heard from anyone else for a long, long time, at least until Barack Obama appeared on the national stage.

Even though they should, many people do not know how how much of NCLB was Teddy Kennedy. When George W. Bush said that he would reach across the aisles to work with the democrats, NCLB was perhaps the most significant evidence of his making good on that pledge.

NCLB is roundly rejected within the arts education community, and in many, many other quarters. What is lost on many of the opponents of NCLB is that it is favored by more people than a group of conservatives. NCLB has had some pretty strong support within low economic urban schools communities, where the local school districts have often failed to provide a sound, basic education. The focus on performance, for many of the parents in these schools, was perhaps the first time in a long time they saw standards and achievement being pushed, measured, and tied to consequences. That focus has meant something to a lot of people.

This is often lost in the din of those who want NCLB ended or significantly overhauled.

Now don't get me wrong: I am not defending NCLB, but rather trying to provide a fair statement as to the side that supports it and why.

While President Obama was highly critical of NCLB on the campaign trail, many people believe that the administration is closely tied to its fundamental premise and will seek to improve it rather shut it down. Politically, that may be a wise move. Without diverting this blog to being about how to improve NCLB, I will simply say for the moment that significantly improving NCLB is much more than tweaking its engine, as there are many, many complicated pieces that would have to be put in place across all fifty states to make a better engine work.

We should get a better sense soon of how this will all shape up.

All of this bring me to a feature on NEA Chair Rocco Landesman in today''s Washington Post:

As for schools, they should encourage young people to soar, not just study for a test. He sneers at the goals of No Child Left Behind, which seem to have little use for arts education. "All the tests don't take into account personal creativity. There is something very American about individualism," he said.After the Bush years, where for the most part the message across the administration was very uniform, and the Bloomberg years in New York City, where the message is completely uniform, it's interesting to see the NEA Chair sneering at the goals of NCLB.

While I have no bone to pick with the goals of NCLB, which is why I think Teddy Kennedy was so much a part of creating and defending it, it is unquestionably a matter of implementation rather than goals.

That being said, it will be very interesting to see how much leeway Landesman is given to press education policy. Will he be reigned in or be the firebrand? Will he become, in effect, the arts czar that many people lobbied for??

This little topic is a tough one. Think about it: according to number of different reports, the NY State ELA tests, which drives just so very much of the educational industrial complex, can be passed by guessing. When arts education is being pushed off the table, out of the school day, etc., look to how the curriculum is narrowed due to the dominance of these tests.

The Daily News covered this story last week:

Would that mean even more resources would be drawn to standardized tests?

Or, perhaps it might be a good teachable moment to think a bit more deeply about what drill and kill is and isn't providing our students.

The Daily News covered this story last week:

The number of correct answers needed to score a Level 2 to get promoted has sunk so low that a student can guess on the multiple choice section and leave the rest of the test blank.GothamSchools.org also covered this last week:

Independent statistician Frederick Smith examined the way free-response questions were graded and found that virtually every student received enough points on that section to then pass the test by guessing randomly on the multiple-choice questions.On her blog for the Huffington Post, Diane Ravitch tied these pieces together and took aim at Arne Duncan and the Obama administration.

Another part of the problem is that the states have been quietly but decisively lowering their expectations and passing students who know little or nothing.What isn't being discussed quite yet, is how it could be that so much money, time, and emphasis is being placed on tests that can be passed just by guessing? With testing, teaching to the test, test prep, supplemental services, and more, all tied together with the only simple measurements readily available to elected officials, well, what happens if the tests are made more difficult?

Would that mean even more resources would be drawn to standardized tests?

Or, perhaps it might be a good teachable moment to think a bit more deeply about what drill and kill is and isn't providing our students.

It's interesting to see the fairly predictable responses to Arne Duncan's letter and web conference, where he articulated support for arts education on behalf of the USDOE and the White House.

There is and should be a fair amount of gratitude across the field when a US Secretary of Education affirms the importance of the arts, even if the affirmation may at first blush appear to be more talk than walk.

And in light of his comments about the central importance of parents to ensuring arts education, well, it was indeed newsworthy.

I think the USDOE is in a bit of a bind. I have come to pretty much believe that Duncan supports the arts. Same for our President. That being said, they have focused their efforts on school "reform" that is heavily weighted towards levers that have little to do with subject matter, save what is measured by ELA/ math standardized tests and graduation rates. In terms of major themes, the USDOE is about data, charter school development, merit pay, etc. Outside of that, there isn't much room to focus on content areas.

Yes there are both the model development and the professional development grant programs, as well NAEP and the Fast Track Survey. In particular, I am a big fan of the grant programs, which are great, really great, believe me, the organization I work for is a current grant recipient. But, when you look at where the real weight of the USDOE is leaning, it's not in this area.

Nevertheless, the rhetorical does have meaning. The bully pulpit does help remind educators of the importance of the arts. Symbolism counts. To a point.

Will a principal take time from test prep because we brandished Arne Duncan's letter reminding them that the arts are a core subject in what we used to call NCLB, but is actually the Elementary and Secondary Education Act?

Probably not, but that's a bit of what is already being proposed by advocates.

If the arts or any other subject for that matter is to be a part of these public themes coming out of the USDOE, it's going to be up to us to find the way in. And yes, that includes the Race to the Top Fund. Who will be able to construct an appropriate arts education project within their state's RTTF application? The state education departments aren't going to do it for us, we have to do it, find a way to bring them on board. Duncan has said as much, a couple of times.

In all fairness, what I am describing is in many ways the very state of arts education in the US. It is up to us to find the openings, to make new alliances, to bring the arts into policy and practice that loom large in education, but have often overlooked and misunderstood arts education.

So, there is it. The Secretary says the right things, but essentially leaves it to us to make his words come true. Perhaps that is the way it should be.

There is and should be a fair amount of gratitude across the field when a US Secretary of Education affirms the importance of the arts, even if the affirmation may at first blush appear to be more talk than walk.

And in light of his comments about the central importance of parents to ensuring arts education, well, it was indeed newsworthy.

I think the USDOE is in a bit of a bind. I have come to pretty much believe that Duncan supports the arts. Same for our President. That being said, they have focused their efforts on school "reform" that is heavily weighted towards levers that have little to do with subject matter, save what is measured by ELA/ math standardized tests and graduation rates. In terms of major themes, the USDOE is about data, charter school development, merit pay, etc. Outside of that, there isn't much room to focus on content areas.

Yes there are both the model development and the professional development grant programs, as well NAEP and the Fast Track Survey. In particular, I am a big fan of the grant programs, which are great, really great, believe me, the organization I work for is a current grant recipient. But, when you look at where the real weight of the USDOE is leaning, it's not in this area.

Nevertheless, the rhetorical does have meaning. The bully pulpit does help remind educators of the importance of the arts. Symbolism counts. To a point.

Will a principal take time from test prep because we brandished Arne Duncan's letter reminding them that the arts are a core subject in what we used to call NCLB, but is actually the Elementary and Secondary Education Act?

Probably not, but that's a bit of what is already being proposed by advocates.

If the arts or any other subject for that matter is to be a part of these public themes coming out of the USDOE, it's going to be up to us to find the way in. And yes, that includes the Race to the Top Fund. Who will be able to construct an appropriate arts education project within their state's RTTF application? The state education departments aren't going to do it for us, we have to do it, find a way to bring them on board. Duncan has said as much, a couple of times.

In all fairness, what I am describing is in many ways the very state of arts education in the US. It is up to us to find the openings, to make new alliances, to bring the arts into policy and practice that loom large in education, but have often overlooked and misunderstood arts education.

So, there is it. The Secretary says the right things, but essentially leaves it to us to make his words come true. Perhaps that is the way it should be.

I know, I know, the full transcript and audio is coming.

In the meantime, here are a few quotes. But before that, here's my headline:

US Education Secretary Affirms the Importance of Parents in Ensuring Arts Education

Here are the highlights:

Thanks to Nicole Mitzel at CAE for the quick transcription of these highlights.

In the meantime, here are a few quotes. But before that, here's my headline:

US Education Secretary Affirms the Importance of Parents in Ensuring Arts Education

Here are the highlights:

1."The elementary and secondary education act defines arts education as a core subject."

2. "The 2008 NAEP assessment of music and visual arts...reminded all of us that the arts are a part of a complete education and require kids to use creative and problem solving skills."

3."Arts education plays an essential part in children's education. It enriches their learning experience and builds skills that they can apply across the curriculum. The arts can play a significant role in programs that extend the school day and the school year."

4."As we think about NCLB reauthorization...I really want to think about how we can create incentives for folks not to narrow the curriculum, and continue to give a complete, comprehensive set of activities and experiences for children."

5."Parents really have to push for this and demand it. And our job as educators is to listen to what parents and students are telling us."

6. "I'd push...three things: better recognizing and rewarding success and excellence and sharing those best practices, supporting the really creative and collaborative partnerships that create these opportunities for students, and really encouraging and empowering parents to make sure that this is the norm rather than the exception."

Thanks to Nicole Mitzel at CAE for the quick transcription of these highlights.

Too Often the Music Dies in City Schools, is a recent article in the Detroit Free Press.

While it's a story we all know too well, cuts to arts education programs, it's worth the read. In particular it looks at the issue through the lens of jazz players who have come out of Detroit Public Schools.

Makes you wish for a music education bailout...

"This year, 14 music teachers retired, and the district replaced none of them."

While it's a story we all know too well, cuts to arts education programs, it's worth the read. In particular it looks at the issue through the lens of jazz players who have come out of Detroit Public Schools.

Makes you wish for a music education bailout...

"This year, 14 music teachers retired, and the district replaced none of them."

If you haven't heard by now, Arne Duncan, US Secretary of Education is having a conference call with just about everyone in the United States interested in arts education. Of course you have to register.

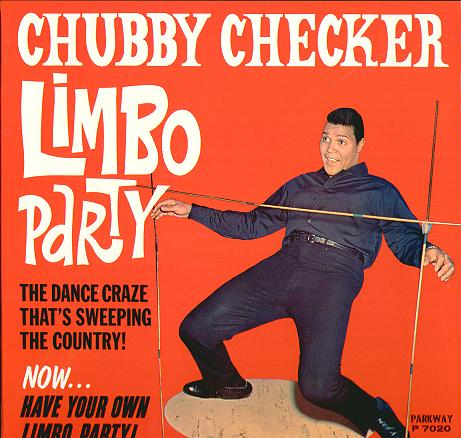

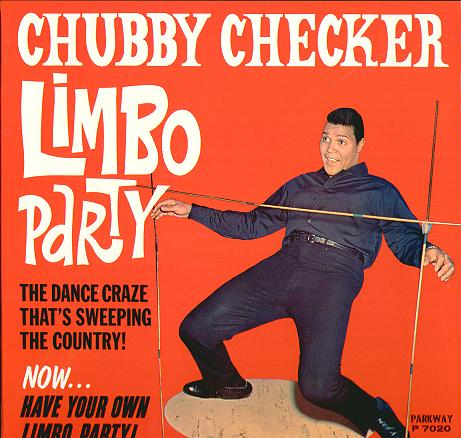

It's like a giant arts ed party line. For those old enough to know what a party line was...

If I were asking a question in the conference call, my question would be:

Mr. Secretary, thank you so much for creating this historic conference call, for recognizing the importance of arts education as a core subject, and for the extraordinary articulation by a US Education Secretary of the importance of arts education to education leaders across the nation.

I would like to hear more from you about how you believe arts education will flourish in light of your desire to see teachers evaluated on student performance on test scores, particularly when such performance is mostly limited to standardized test scores in reading and math.

What's your question for Arne Duncan???

Dated August 2009, here's a open letter to "School and Education Community Leaders."

Arts Education Letter_Secretary Duncan.pdf

Arts Education Letter_Secretary Duncan.pdf

On August 18th, at 1pm EDT, Secretary Duncan will participate in a conference call hosted by the NAMM Foundation and the Support Music Coalition. Click here to register for the call:

I am sure by now that you've come across this, as it has already been posted to all sorts of blogs and appeared in the news. But hey, this is August, the dog days of summer, so maybe you've missed it.

It is perhaps one of the most original takes on the arts in America, making the case for the arts as service to the nation, thereby establishing a relevance above and beyond what is ordinarily expressed.

I would sure love to know more about this, such as: did she write it herself? Did Ella Baff help her just a bit? I hope that we will hear more from Ms. Maddow on this subject.

It is perhaps one of the most original takes on the arts in America, making the case for the arts as service to the nation, thereby establishing a relevance above and beyond what is ordinarily expressed.

I would sure love to know more about this, such as: did she write it herself? Did Ella Baff help her just a bit? I hope that we will hear more from Ms. Maddow on this subject.

"Sometimes we choose to serve our country in uniform, in war. Sometimes in elected office. And those are the ways of serving our country that I think we are trained to easily call heroic. It's also a service to your country, I think, to teach poetry in the prisons, to be an incredibly dedicated student of dance, to fight for funding music and arts education in the schools. A country without an expectation of minimal artistic literacy, without a basic structure by which the artists among us can be awakened and given the choice of following their talents and a way to get to be great at what they do, is a country that is not actually as great as it could be. And a country without the capacity to nurture artistic greatness is not being a great country. It is a service to our country, and sometimes it is heroic service to our country, to fight for the United States of America to have the capacity to nurture artistic greatness." -- MSNBC's Rachel Maddow, speaking at Jacob's Pillow

Or is it?

Okay, I was intentionally provocative in my title. Not just in using the term "regulate," but in using the declarative form rather than the interrogative.

Should we start regulating teaching artists? Do you like that better?

In the past two weeks I have had two different conversations with members of the New York State Board of Regents involving the matter of teaching artists and certification. Add to that a lunch last Friday where a few of us bounced this issue around. A few months before that a major foundation raised the issue with me.

The first time I encountered this particular topic within arts education, was in 1994, when I was part of the consulting team charged with developing the arts education proposal for the Annenberg Foundation, that eventually led to the creation of The Center for Arts Education.

Fifteen years later, the whole area remains a wild west.

The general lay of the land includes the following:

1. Many feel the quality of work by teaching artists varies greatly (duh, like everything else), and beyond the natural variances, is due in large part to the ways in which teaching artists are recruited, trained, booked, and supported.

2. Some organizations train their teaching artists; others don't. And in between, there are countless variations on the approach to training, including duration, formal versus informal, use of practicum model, use of master teachers, ongoing support, curriculum, and more.

3. The role of the teaching artist is so varied. There are teaching artists working in ensemble, working solo, working in residencies of greatly varying duration. There are teaching artists functioning as de facto arts teachers; teaching artists doing auditorium programs, and more. There are teaching artists who essentially freelance on the rosters of multiple organizations, a handful of teaching artists fully and exclusively employed by organizations (with benefits), and others, a growing faction, who function as sole proprietors, essentially booking themselves directly with schools.

4. As the field of education has become increasingly complex and crowded, particularly in terms of data/testing, and special needs, many believe the field of teaching artists have fallen behind. Moreover, many feel that the field was always weak in regards to basic teaching skills that would be expected of anyone entering a classroom on a formal and professional basis.

5. The role of the teaching artist overlaps with community interests and programs beyond the school walls. More and more teaching artists are involved with work in the community, from family engagement, to work in social justice, and more.

6. Unlike teachers, there is no certification process. Moreover, there is no real regulation other than that of the market, which many people believe doesn't work very well from a quality perspective. Yes, some organizations self-regulate, as in assess the work of their artists and drop those off their rosters who are not up to the task. But there is no formal regulation across a geographic area that I know of.

Oddly enough, even with the enormous certification structures out there for teachers in America, there is major league disenchantment with those certification processes, regulation, etc., and many people are pushing for a growth in alternative certification. It's a big part of all the sturm and drang associated with teacher quality, Teach for America, etc.

So, what do people want?

Many organizations want to be left alone, to continue their own way of providing what they believe are high quality teaching artists. In many ways, this is purely a market-based approach.

Many people who are policy and systems oriented want to see some sort of regulation adopted. This could be a type of certification program, required for new teaching artists and grandfathered in for existing. That's one way to do it, probably the most politically expedient. Another would be to have some process to evaluate and certify everyone. It could be done through the various state departments of education, or even through local school districts.

Some people are more interested in taking stock of where we are today. How are the new training/certification programs such as the one emerging in Philadelphia going to work out? How is it structured? What are the various training programs across the country? What are the similarities and differences? What is truly unique that we could all learn from?

What exactly do schools want to see and what do teaching artists themselves articulate as their needs in training, skills, and knowledge?

How do people envision the complications of regulating teaching artists that are already practicing? Should they be paid to train? Is it on a volunteer basis? A pilot basis?

Can you develop the capacities of the schools to really drive this issue, for the schools could ultimately establish quality market forces. For example, if schools wanted to know that the teaching artists being offered to them by their partner organizations had skills in classroom management or development trends, well then, the organizations would certainly respond to that demand, through training and assessment.

I think that this is a great moment for us to take a topological view and create a map that would help us understand where we are today and where we should go. Otherwise, well, 15 years from now it might just be 1994 all over again.

And now for my sort of disclaimer: yes, I was a teaching artist, for about 15 years. Yes, I was deeply involved in the training of teaching artists, for a good six or seven years, although I do very little of it today. Yes, the organization I work for is involved in the training of teaching artists, as well as other work with teaching artists.

Okay, I was intentionally provocative in my title. Not just in using the term "regulate," but in using the declarative form rather than the interrogative.

Should we start regulating teaching artists? Do you like that better?

In the past two weeks I have had two different conversations with members of the New York State Board of Regents involving the matter of teaching artists and certification. Add to that a lunch last Friday where a few of us bounced this issue around. A few months before that a major foundation raised the issue with me.

The first time I encountered this particular topic within arts education, was in 1994, when I was part of the consulting team charged with developing the arts education proposal for the Annenberg Foundation, that eventually led to the creation of The Center for Arts Education.

Fifteen years later, the whole area remains a wild west.

The general lay of the land includes the following:

1. Many feel the quality of work by teaching artists varies greatly (duh, like everything else), and beyond the natural variances, is due in large part to the ways in which teaching artists are recruited, trained, booked, and supported.

2. Some organizations train their teaching artists; others don't. And in between, there are countless variations on the approach to training, including duration, formal versus informal, use of practicum model, use of master teachers, ongoing support, curriculum, and more.

3. The role of the teaching artist is so varied. There are teaching artists working in ensemble, working solo, working in residencies of greatly varying duration. There are teaching artists functioning as de facto arts teachers; teaching artists doing auditorium programs, and more. There are teaching artists who essentially freelance on the rosters of multiple organizations, a handful of teaching artists fully and exclusively employed by organizations (with benefits), and others, a growing faction, who function as sole proprietors, essentially booking themselves directly with schools.

4. As the field of education has become increasingly complex and crowded, particularly in terms of data/testing, and special needs, many believe the field of teaching artists have fallen behind. Moreover, many feel that the field was always weak in regards to basic teaching skills that would be expected of anyone entering a classroom on a formal and professional basis.

5. The role of the teaching artist overlaps with community interests and programs beyond the school walls. More and more teaching artists are involved with work in the community, from family engagement, to work in social justice, and more.

6. Unlike teachers, there is no certification process. Moreover, there is no real regulation other than that of the market, which many people believe doesn't work very well from a quality perspective. Yes, some organizations self-regulate, as in assess the work of their artists and drop those off their rosters who are not up to the task. But there is no formal regulation across a geographic area that I know of.

Oddly enough, even with the enormous certification structures out there for teachers in America, there is major league disenchantment with those certification processes, regulation, etc., and many people are pushing for a growth in alternative certification. It's a big part of all the sturm and drang associated with teacher quality, Teach for America, etc.

So, what do people want?

Many organizations want to be left alone, to continue their own way of providing what they believe are high quality teaching artists. In many ways, this is purely a market-based approach.

Many people who are policy and systems oriented want to see some sort of regulation adopted. This could be a type of certification program, required for new teaching artists and grandfathered in for existing. That's one way to do it, probably the most politically expedient. Another would be to have some process to evaluate and certify everyone. It could be done through the various state departments of education, or even through local school districts.

Some people are more interested in taking stock of where we are today. How are the new training/certification programs such as the one emerging in Philadelphia going to work out? How is it structured? What are the various training programs across the country? What are the similarities and differences? What is truly unique that we could all learn from?

What exactly do schools want to see and what do teaching artists themselves articulate as their needs in training, skills, and knowledge?

How do people envision the complications of regulating teaching artists that are already practicing? Should they be paid to train? Is it on a volunteer basis? A pilot basis?

Can you develop the capacities of the schools to really drive this issue, for the schools could ultimately establish quality market forces. For example, if schools wanted to know that the teaching artists being offered to them by their partner organizations had skills in classroom management or development trends, well then, the organizations would certainly respond to that demand, through training and assessment.

I think that this is a great moment for us to take a topological view and create a map that would help us understand where we are today and where we should go. Otherwise, well, 15 years from now it might just be 1994 all over again.

And now for my sort of disclaimer: yes, I was a teaching artist, for about 15 years. Yes, I was deeply involved in the training of teaching artists, for a good six or seven years, although I do very little of it today. Yes, the organization I work for is involved in the training of teaching artists, as well as other work with teaching artists.