Dewey 21C: July 2009 Archives

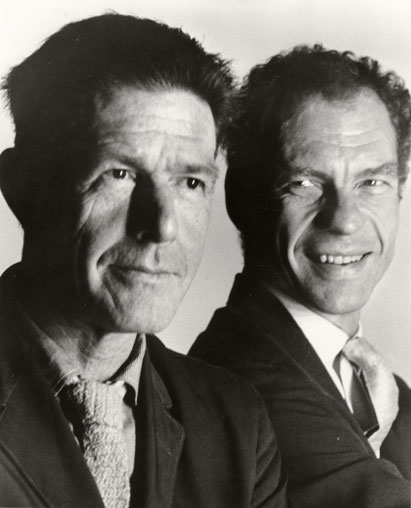

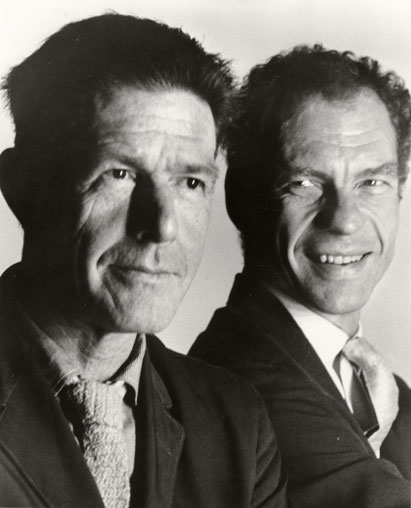

I wanted to end this very hot. humid, and WET New York summer week by recalling a swell dinner I had once with Merce Cunningham and Laura Kuhn, Director of The Cage Trust.

I won't recount what the obits and testaments said very well about Merce as a truly giant, emblematic figure of modern dance and creativity in American during the 20th and early 21st centuries. I have something to add to it.

When I worked at the American Music Center, I was fortunate to have gotten to know Merce a little bit. Some parties at his house, many performances, funding for the music in a number of his pieces through the AMC's Live Music for Dance Program, and in particular, through Laura Kuhn, who ran The Cage Trust (as in John Cage) was on the AMC Board of Directors.

We had gone through a very rough patch at the AMC, but managed to weather the storm and come out stronger. As a sort of reward for the hard work, Laura arranged for a dinner at Merce's apartment.

Coming primarily from the music side of things, I was equally as interested in hearing from Merce about John Cage, and the countless other great, great composers he worked with and hung out with in that "New York School." Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, David Tudor--gosh, there were so many connected to Merce's life and work.

I remember just so very well, and probably will never forget Merce bringing me over to John Cage's leather couch--positioned by a window. Merce said it was basically left where John Cage left it, where he loved to sit. It was in the little mind's eye picture of John that Merce painted for me.

We got to talking about technology. If you don't know, Merce did some quite remarkable work with technology over the past decade and a half. I had recently seen Biped a work that Merce partnered with two technologists: Paul Kaiser and Shelly Eshkar. Gavin Bryars composed the music.

You can see a clip from the work here. I thought it was an absolute stunning piece.

Even better! Here is an interactive feature from The New York Times, where Alastair Macaulay dissects a clip from Biped.

It's not really evident from my posts, I guess, that I am a technology nut. Okay, there was one post, but you probably missed it.

Back to the matter at hand...

So, Merce and I got to talking about technology and what seemed like a giant frontier in 1999/2000, which is around when that dinner took place.

I remember two things:

1. He was as nice, thoughtful, and respectful as could be. It was truly a lovely dinner and his gentle quality that night had a grace to it that I will never forget. He thanked me for my work at the American Music Center. Okay, that WAS a reward for the hard work!

2. He said something to me that I will also never, never forget. I think about it often, as it was and still is one of the most remarkable commentaries on arts in America that I have ever heard.

Okay, what did he say? When we were talking about technology, all sorts of ideas were popping, from Merce, of course, from Laura, and from me.

At one point Merce stopped, looked right at me, and said, "I have so many ideas, if I only had the funding."

Here I was with Merce Cunningham, who was lamenting not having the money to create. One of the greatest American artistic treasures of the 20th century, was in many ways just like the rest of us, wondering what he could really do if he had the money, to create, to experiment.

My thoughts in response were in hindsight policy-oriented. It felt to me that we were denying ourselves as a nation, by denying Merce Cunningham. It felt that we should as a matter of national policy, be fueling artists of this caliber.

Okay, it's not the first time I had run into it. I knew of the hard work that Steve Reich had to do to get any number of projects completed. I knew, of course, of the support that Betty Freedman had given to both of these artists, Cunningham and Reich, and countless others, including John Cage. Some were near broke when Betty kept their heads above water.

There has been a lot of talk about cultural policy in America, fueled by those who called for an arts czar.

Here's a bit of "national cultural policy" for ya: when great artists such as Cunningham emerge, fund them. Give them money to create, to experiment, to fail, to succeed; to dream the biggest dream they can. Give them money, straight out of the Federal Reserve. Hot off the printing presses.

We say that there are companies "too big to fail." In this case, there are artists too big, too great, to be working on an allowance.

They tell you not to sweat the "small stuff; it's all small stuff."

What I see here, is that among the many pressing needs for education in New York State, according to The New York Times editorial, arts education is on the map. And not only that, the Times called it right--it is a "widely seen lack of arts education..."

You tell me: is this small or large? One sentence in today's New York Times editorial on the selection of David Steiner as the new NYS Commissioner of Education:

"And as a former director of arts education at the National Endowment for the Arts, he is also well suited to deal with what is widely seen as a lack of arts education in the public schools."

What I see here, is that among the many pressing needs for education in New York State, according to The New York Times editorial, arts education is on the map. And not only that, the Times called it right--it is a "widely seen lack of arts education..."

I would like to think that such small things are indicators of some sort of rewriting of the map of public education in New York. Having more and better data on arts education in the New York City public schools (thanks to the NYCDOE), coupled with people and organizations willing to sustain the getting out of the word on need, is certainly helping the cause.

Is it the solution? Of course not, silly. It's one of the key pieces of the puzzle. Without a clear understanding of the need, and sustained work to build the number of people who both understand the need, value its importance, and have the tools and support to act upon such information and value, well, you don't stand much of a chance.

David Steiner, whom some of you will remember as the Director of Arts Education at the National Endowment for the Arts (he was Sarah Cunningham's predecessor), is set to be announced as the new Commissioner of Education in New York State. The Board of Regents is expected to announce this today.

Steiner is presently Dean of Hunter College's School of Education.

I cannot recall a K-12 education issue in New York City higher profile than that of the renewal of the 2002 School Governance Law, aka "Mayoral Control of the Schools."

Everyone concerned with K-12 education in New York City, as well many across the country have been watching this issue to see whether Mayor Michael Bloomberg would retain near absolute control of the schools when the law was up for renewal or whether change would be made, effectively diminishing his control of the schools.

For a good year and a half, hearing have been held, papers written, commissions convened, giant amounts of media space taken, and the highest profile political battle was waged. Last week, it appears to have drawn to a conclusion with a deal made between leaders of the NY State Senate and Mayor Bloomberg.

Among the amendments to the law on school governance will be the creation of an independent arts education council, to serve as a type of watchdog over the New York City public schools. This will be written into New York State Law. Of course, the Senate deal needs to be agreed to be the Assembly, which has its own bill, but most people believe the Senate deal will hold up.

It is a very, very big win for what in and of itself is a relatively small but important step forward.

I have been in arts education one way or the other since about 1982, when I was performing in public and private schools around New York City while getting my bachelor's and master's degrees at The Juilliard School.

I have always been told that, and witnessed, arts education as something that would forever be many rungs down the ladder when it came to educational priorities. The exceptions have been truly rare and almost never part of a planned and sustained sequence, mainly because there really was no real sustained work taking place on the policy and advocacy level. Advocacy and arts is and has been a very nascent and I would argue ham-fisted endeavor.

With something as big as mayoral control of the schools, I doubt many believed that arts education could have become a point of contention in the debate and negotiations between the State Senate, and one of the most powerful men in the world, who also happens to reportedly be the single largest donor to arts in America.

And, you must consider that the Mayor's position was that he would accept no compromise, meaning no changes to the law. And, believe me, this Mayor is loathe to compromise. He's one tough customer, as my dad used to say.

A few weeks ago, State Senator John Sampson was publicly sparring with Mayor Bloomberg over arts education as a key point of contention between Senate leadership and the Mayor. And any number of senators spoke loudly and advocated for the arts education amendment.

I heard it the radio; read it in the papers: arts education getting top billing.

It was what I was always told could not happen. Arts Education had leapt up to the top few issues within the most important K-12 policy debate in New York City and State over perhaps the past thirty years. An issue big enough for Arne Duncan, Secretary of Education to get involved with the type of local issue that such federal officials always avoid.

You're probably thinking that I am exaggerating. Or that I am an hysteric. I am not, I promise.

There are many who will say: "so what, the Council is meaningless. It has no real power and authority."

To that I answer that we shall see how the Council shapes up, and that one way or the other being able to move the arts into this high profile arena sets the stage for other legislation that will do more and better. Remember, this did not happen by chance. What made this possible was thoughful work in policy, the development of a web of relationships, good communications, and a clear interest and willingness on behalf of people who are not from the arts education ghetto, so to speak, where most of the talk of advocacy and policy has taken place during my professional life.

This type of work in policy and advocacy has to be built in stages. I will take this win, and look forward greatly to a number of other policy and advocacy initiatives in the pipeline as you read this.

There's been quite a bit of coverage concerning the acquisition of WQXR, one of the last commercial classical radio stations in America, by the local public radio station, WNYC. WQXR is being sold by The New York Times. It was for many years "The Radio Station of The New York Times."

I won't bother to go over the details as reported, but there is one thing that gives me great, great pause, that somehow or another has gone unreported.

According to everything I've read, it appears that WNYC's Evening Music is going to disappear.

Many years ago, I was once a fan, a big fan of WQXR. I grew up listening to it, along with WNCN and WNYC. New York had three great classical radio station, not to mention WKCR, the radio station of Columbia University. Not to digress, but if you want to hear truly great and inspired radio programming, WKCR has a twice yearly festival of Bach. That's all they play for something like a week. It's revelation.

I stopped listening to WQXR years ago, because it became one of the many classical stations that provides classical wallpaper music. The music is designed to fill up space in the background of restaurants, dentist offices, etc., with benign, short, classical music that works well while you are getting a post and crown done at the prosthodontist. Yes, there are a few live concerts that to me are the exceptions that prove the rule.

WNYC's evening music took on a new host about a year and a half ago: Terrance McKnight. The programming on his show makes sense to me, in how it blends genres, how it is allowed to play a wide range of music; a fair amount of it new, some of it pop, even while still being part of the umbrella of what is now known as "classical music" in America.

As corny is it sounds, Evening Music restored my faith in classical music on public radio.

Around the time I stopped listening to WQXR, it dawned upon me that much of the music they played was music that I had never heard, nor was interested in: obscure composers from 17th-19th centuries. But hey, let's not forget, I have two music degrees from Juilliard, and I hadn't heard of these people. Okay, call me elitist. But isn't elitism a good part of what classical music is all about?

While everyone is apparently happy about the rescue of WQXR, and a group of big named artists have banded together to help raise money to pay for the cost of all this, perhaps they should ask a few questions about what is played on WQXR, what is played on WNYC, and what exactly is going to be lost and gained?

It's just possible, that if these artists listen to WQXR for a just moment, that they won't be so happy with what appears to be the answer.

I won't bother to go over the details as reported, but there is one thing that gives me great, great pause, that somehow or another has gone unreported.

According to everything I've read, it appears that WNYC's Evening Music is going to disappear.

Many years ago, I was once a fan, a big fan of WQXR. I grew up listening to it, along with WNCN and WNYC. New York had three great classical radio station, not to mention WKCR, the radio station of Columbia University. Not to digress, but if you want to hear truly great and inspired radio programming, WKCR has a twice yearly festival of Bach. That's all they play for something like a week. It's revelation.

I stopped listening to WQXR years ago, because it became one of the many classical stations that provides classical wallpaper music. The music is designed to fill up space in the background of restaurants, dentist offices, etc., with benign, short, classical music that works well while you are getting a post and crown done at the prosthodontist. Yes, there are a few live concerts that to me are the exceptions that prove the rule.

WNYC's evening music took on a new host about a year and a half ago: Terrance McKnight. The programming on his show makes sense to me, in how it blends genres, how it is allowed to play a wide range of music; a fair amount of it new, some of it pop, even while still being part of the umbrella of what is now known as "classical music" in America.

As corny is it sounds, Evening Music restored my faith in classical music on public radio.

Around the time I stopped listening to WQXR, it dawned upon me that much of the music they played was music that I had never heard, nor was interested in: obscure composers from 17th-19th centuries. But hey, let's not forget, I have two music degrees from Juilliard, and I hadn't heard of these people. Okay, call me elitist. But isn't elitism a good part of what classical music is all about?

While everyone is apparently happy about the rescue of WQXR, and a group of big named artists have banded together to help raise money to pay for the cost of all this, perhaps they should ask a few questions about what is played on WQXR, what is played on WNYC, and what exactly is going to be lost and gained?

It's just possible, that if these artists listen to WQXR for a just moment, that they won't be so happy with what appears to be the answer.

Tomorrow will be the first anniversary of Dewey21c, and I will celebrate by eating some croissants (there's a killer place for croissants and macroons around the corner), I thought I would end my first year of Dewey21c, which would be something like the 144th published entry, with a story about arts education through the lens of Pierre Boulez and Christoph von Dohnanyi.

144 entries; 365 days. All arts education.

In the late mid 90's, I was working on an arts education plan for The Cleveland Orchestra. Then and still Director of Education, Joan Katz Napoli, and I went to meet with the orchestra's music director, Dohnanyi, and the orchestra's guest conductor, Boulez, in order to bring them into the conversations that were taking place across the orchestra's community to help design this plan. We met with each separately.

I had worked with a number of orchestras in developing similar plans, and while we were given significant access to board, staff, musicians, and people throughout the communities, we rarely met with the music directors, which I always thought was quite odd. In Baltimore, for example, we met with virtually everyone but David Zinman, the then music director. Naturally, I always thought this was an unfortunate loss and a commentary on the orchestra industry culture.

So, Cleveland really went that extra mile and not only arranged time with its music director, but with perhaps the most famous living conductor in the world (not to mention his role as a composer and musical citizen): Pierre Boulez.

These two sides of the same coin speak volumes about arts education then and today, as well as, naturally, the culture of orchestras and classical music.

Long story short: after all the lovely pleasantries with Dohnayni, this was a quick meal at his home, we made our pitch about deepening the orchestra's relationship with public schools in the Cleveland area. Dohnanyi was quick to reply. Essentially he said (yes, I am paraphrasing, from 12 year old notes!):

And, that was that, as they say.

Next up, a brief meeting with Boulez. Again, we make our pitch, wanting to seek his advice, learn from his experiences, yadda, yadda. Oddly enough, when I was in All-City High School Orchestra in the New York City public schools, Pierre Boulez conducted us in a side-by-side with the New York Philharmonic, and separately.

So, Boulez gave it a moment's thought, and out he came with a flash of arts education brilliance:

Essentially he said:

And that was that.

So, 140 posts later, that will be that for my first year.

144 entries; 365 days. All arts education.

In the late mid 90's, I was working on an arts education plan for The Cleveland Orchestra. Then and still Director of Education, Joan Katz Napoli, and I went to meet with the orchestra's music director, Dohnanyi, and the orchestra's guest conductor, Boulez, in order to bring them into the conversations that were taking place across the orchestra's community to help design this plan. We met with each separately.

I had worked with a number of orchestras in developing similar plans, and while we were given significant access to board, staff, musicians, and people throughout the communities, we rarely met with the music directors, which I always thought was quite odd. In Baltimore, for example, we met with virtually everyone but David Zinman, the then music director. Naturally, I always thought this was an unfortunate loss and a commentary on the orchestra industry culture.

So, Cleveland really went that extra mile and not only arranged time with its music director, but with perhaps the most famous living conductor in the world (not to mention his role as a composer and musical citizen): Pierre Boulez.

These two sides of the same coin speak volumes about arts education then and today, as well as, naturally, the culture of orchestras and classical music.

Long story short: after all the lovely pleasantries with Dohnayni, this was a quick meal at his home, we made our pitch about deepening the orchestra's relationship with public schools in the Cleveland area. Dohnanyi was quick to reply. Essentially he said (yes, I am paraphrasing, from 12 year old notes!):

"Why would we do this? I don't see how we could have a fruitful relationship with students who were not deeply involved and advanced in the study of classical music. There would be no common language. I could understand working with advanced high school students or conservatory students."

And, that was that, as they say.

Next up, a brief meeting with Boulez. Again, we make our pitch, wanting to seek his advice, learn from his experiences, yadda, yadda. Oddly enough, when I was in All-City High School Orchestra in the New York City public schools, Pierre Boulez conducted us in a side-by-side with the New York Philharmonic, and separately.

So, Boulez gave it a moment's thought, and out he came with a flash of arts education brilliance:

Essentially he said:

"In thinking about orchestras working with young people, you have to consider that symphonic music is based on memory and respect. Children don't care about such things, they are about spontaneity and creativity. In order to develop something worthwhile, you would have to bridge the gap between memory and respect, and spontaneity and creativity."

And that was that.

So, 140 posts later, that will be that for my first year.

The "arts czar" idea is still buzzing about. Of course, the actor Kal Penn was appointed to the White House Office of Public Engagement, and we will have Rocco Landesman heading up the NEA, and Jim Leach heading up the NEH. But certainly, that's a far cry from what a number of people were lobbying for, which was a cabinet level position in the executive branch, replete with its own brand new agency. What a great idea....not.

This week Michael Kaiser brought up the issue of a federal arts policy. The best thing he said about this was "what we really need is a debate over federal arts policy." Agreed. I would prefer to leave it there. Let's have a debate. Let's foster sustained opportunities to engage the nation in conversations around federal policy for arts. I hope that Mr. Kaiser, from his position at The Kennedy Center, and the expanding stage through his books, writings, consultancies, etc., will spearhead such an effort.

To get the ball rolling, I want to look one of Kaiser's assertions:

Of course, that depends on the results you are after and whether the objectives/goals/standards can be developed in a way that makes great sense, not just a good start, up against the giant, always moving target of education, of which arts education is or should be more of a part than arts and culture. Let me say that in a slightly different way: K-12 arts education should be more connected to the field of education, than to arts. And of course, along with that comes the need to connect to the policy churn of K-12 education overall. Which by definition means that arts education policy will have to remain highly flexible and nimble, including related programming, etc.

Naturally, this is nothing new, it's the history. When the NEA was about the integration of the arts, the field followed. When it became about artistic quality, the field followed. When Attendance Improvement Drop Out Prevention (AIDP) was big, the field followed. When School to Work was big, etc., etc. When Charter Schools became the rage, organizations started creating them, well, some are starting...

Call me crazy or obtuse, but hey, I like the fact that there was an opportunity to apply to the United States Department of Justice for a grant to develop a mentoring program. I like that the USDOE arts education program is very different from that of the National Endowment for the Arts. When I was at the American Music Center, I liked the opportunity to apply to the United States Department of Transportation for a grant (we didn't get it...)

To me, there is beauty and opportunity in somewhat divergent, but well-crafted guidelines coming from a variety of federal agencies that hew more to the variety of approaches in arts education that what I fear would be the case under a more "effective and efficient" or more coordinated effort. Each arts education organization already has a set of state standards to address. Moreover, there's a push now, that darn churn again, dammit, to create a national set of standards in every subject area.

If we're talking about coordinating the bully pulpit at the federal level, that's another story entirely, and a great idea. In many ways, I think that was the best of what Dana Gioia did during his tenure at the NEA. I would love to see that bully pulpit expanded. I think that was what "Q" as his friends like to call him, was after with lobbying for an arts czar.

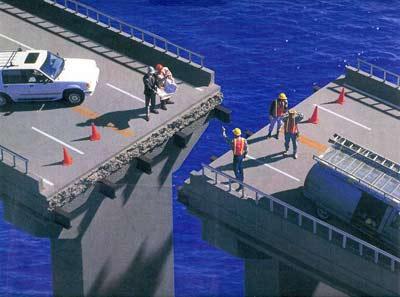

I do find it funny, that the term of art (quasi pun intended), is the "arts czar." Just like the "Car Czar." Usually those governmental czar appointments are to correct something, look at the Car Czar. Or, look at the "Pay Czar," connected to TARP. Do the arts need a czar?

While in Russia it may be au courant to lionize the days of the czar, is that what we really want? It didn't work out very well for my family back in Odessa, except, I guess, that they finally left for America, or were forced to leave.

As for whether the efficient and effective results can be had in the larger field of arts and culture, well beyond arts education, where things are even more kaleidoscopic, that's for another entry.

This week Michael Kaiser brought up the issue of a federal arts policy. The best thing he said about this was "what we really need is a debate over federal arts policy." Agreed. I would prefer to leave it there. Let's have a debate. Let's foster sustained opportunities to engage the nation in conversations around federal policy for arts. I hope that Mr. Kaiser, from his position at The Kennedy Center, and the expanding stage through his books, writings, consultancies, etc., will spearhead such an effort.

To get the ball rolling, I want to look one of Kaiser's assertions:

At first blush it sounds good, I know. Who wouldn't want effective and efficient results? And coordinating arts education programming, as well as spending across federal agencies, sounds like a great idea too, doesn't it? Or does it?"Those of us in the arts are grateful for the many opportunities presented for federal support. The problem is that there is literally no coordination between these agencies on their arts spending, nor is there any central governing philosophy or policy.

For example, grants for arts education are given by several agencies yet there is no effort to coordinate the educational programming of the arts organizations receiving federal funds. This cannot yield the most effective or efficient results.

For example, grants for arts education are given by several agencies yet there is no effort to coordinate the educational programming of the arts organizations receiving federal funds. This cannot yield the most effective or efficient results."

Of course, that depends on the results you are after and whether the objectives/goals/standards can be developed in a way that makes great sense, not just a good start, up against the giant, always moving target of education, of which arts education is or should be more of a part than arts and culture. Let me say that in a slightly different way: K-12 arts education should be more connected to the field of education, than to arts. And of course, along with that comes the need to connect to the policy churn of K-12 education overall. Which by definition means that arts education policy will have to remain highly flexible and nimble, including related programming, etc.

Naturally, this is nothing new, it's the history. When the NEA was about the integration of the arts, the field followed. When it became about artistic quality, the field followed. When Attendance Improvement Drop Out Prevention (AIDP) was big, the field followed. When School to Work was big, etc., etc. When Charter Schools became the rage, organizations started creating them, well, some are starting...

Call me crazy or obtuse, but hey, I like the fact that there was an opportunity to apply to the United States Department of Justice for a grant to develop a mentoring program. I like that the USDOE arts education program is very different from that of the National Endowment for the Arts. When I was at the American Music Center, I liked the opportunity to apply to the United States Department of Transportation for a grant (we didn't get it...)

To me, there is beauty and opportunity in somewhat divergent, but well-crafted guidelines coming from a variety of federal agencies that hew more to the variety of approaches in arts education that what I fear would be the case under a more "effective and efficient" or more coordinated effort. Each arts education organization already has a set of state standards to address. Moreover, there's a push now, that darn churn again, dammit, to create a national set of standards in every subject area.

If we're talking about coordinating the bully pulpit at the federal level, that's another story entirely, and a great idea. In many ways, I think that was the best of what Dana Gioia did during his tenure at the NEA. I would love to see that bully pulpit expanded. I think that was what "Q" as his friends like to call him, was after with lobbying for an arts czar.

I do find it funny, that the term of art (quasi pun intended), is the "arts czar." Just like the "Car Czar." Usually those governmental czar appointments are to correct something, look at the Car Czar. Or, look at the "Pay Czar," connected to TARP. Do the arts need a czar?

While in Russia it may be au courant to lionize the days of the czar, is that what we really want? It didn't work out very well for my family back in Odessa, except, I guess, that they finally left for America, or were forced to leave.

As for whether the efficient and effective results can be had in the larger field of arts and culture, well beyond arts education, where things are even more kaleidoscopic, that's for another entry.

Here is a story from WNYC.org, which is based upon its Brian Lehrer program yesterday, where John Sampson, the democratic leader of the gridlocked New York State Senate explained the changes he wanted to make to the law governing the New York City Public Schools.

If you're not from New York, here's a brief recap: the law that gives the Mayor of New York near complete control of the public schools expired on June 30th. There is a bill in one of the two State houses that has been passed, which basically leaves the mayor's control intact, and everyone is waiting on the gridlocked Senate, the other house, to resolve the question of which party is in power, so it can presumably debate the bill and vote, which would ultimately send something to Governor Paterson for his signature.

Senator Sampson has introduced his own school governance legislation, and yesterday on WNYC, he was asked what changes he wanted to make and why.

Here's a quote as reported on the WNYC website:

Click here to listen to the program in full.

If you're not from New York, here's a brief recap: the law that gives the Mayor of New York near complete control of the public schools expired on June 30th. There is a bill in one of the two State houses that has been passed, which basically leaves the mayor's control intact, and everyone is waiting on the gridlocked Senate, the other house, to resolve the question of which party is in power, so it can presumably debate the bill and vote, which would ultimately send something to Governor Paterson for his signature.

Senator Sampson has introduced his own school governance legislation, and yesterday on WNYC, he was asked what changes he wanted to make and why.

Here's a quote as reported on the WNYC website:

REPORTER: Sampson says he and his colleagues want more funding for arts education, more training for parents, to get them involved in their child's education, and more accountability. Mayor Bloomberg brushed aside those suggestions.Click here to read the article.

BLOOMBERG: I have no idea what he's talking about. I think that's the nicest way to phrase it. We are trying very hard to have a great arts program. I want the teachers and the principals to run the schools, not the parents.

Click here to listen to the program in full.

We must hold ourselves -- our parents, our students, our elected officials, our school administrators -- accountable on arts education.

Some of you may have read about the gridlock taking place presently up in Albany, the New York State Capitol. Basically, the State Senate is locked in place over the question of which party is going to be in power. And, there are some big-time bills that have been tabled as a result of this gridlock, including the bill on School Governance in the New York City Public Schools, aka "Mayoral Control."

Senator Jose M. Serrano published an Op-Ed piece in today's edition of the Gotham Gazette, which is an important local source for news of government in New York State. It's published by Citizen's Union, a good government organization.

Senator Serrano gets it, arts education being the "it." And, he's willing to work to make it happen.

It's touching, and inspiring to see his leadership on this issue, and his willingness to partner with others.His father, US Congressman Jose E. Serrano, has been strong on this issue too.

Give this piece a read, please, I can assure you, he means what he says and it is without a doubt an honest expression of what he believes in and is working towards.

Click here to read Saving Arts Education from Politics, by Senator Jose M.Serrano.

The issue of arts education brings us to the basic question of what type of society we wish to build.

Creativity is the opposite of conformity and is nurtured by a supportive, positive environment that allows students to engage in creative play and honest communication; a place where their fears and vulnerabilities are, at least, acknowledged and not ridiculed.

On this last workday before the July 4th holiday weekend, I would like to share with you a piece by Linda Starkweather, who teaches theater at Eastridge High School's School of Performing Arts in Irondequoit, New York.

Linda's article appeared in New York Teacher, the magazine from my good friends and colleagues at the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT), which is the state-wide teachers' union in New York.

It's a touching article, from someone in the trenches.

Click here to read POV: The Challenge of Teaching Art in the Public School System

Here's an excerpt:

Most teachers have heard, and indignantly bristle, at the mean-spirited phrase, Those who can do, do. Those who can't do, teach. But the dilemma facing public schools -- with the realization that the arts might be important, if not essential, in cultivating the imagination and creativity of our children in order to reverse the blind progress of a culture gone mad with greed and individual success -- is that they need artists to teach the arts. And artists, by their very nature, do not respond to institutionalized fear as motivation. The world has become a place of terror and uncertainty, fueled by institutions that have learned the secret of controlling their members quite effectively by using fear. Although our government has the monopoly on this strategy, most institutions are operating within that same paradigm.

I am really happy to be able to bring you an interview with two really swell colleagues of mine: Stephen Yaffe and Don Glass, who have teamed up on Making Room At The Table: A Needs Assessment of Arts Education for Special Needs Students in New York City Public Schools. Stephen is the principal investigator and Don has authored the introduction. I have had the great pleasure of working with Stephen, as he is the evaluator on the Teacher Artist Training Institute at CAE. I have known Don since he was a research associate at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform.

Stephen and Don were kind enough to take some time from their busy schedules to participate in this interview for Dewey21C.

DG: Richard, thanks for providing this opportunity to share the findings of this study. Stephen Yaffe approached VSA arts with the idea to conduct a needs assessment on the status of arts education for students with disabilities in New York City. We saw it as a way to invest in an important study that could inform the work of our local affiliate and like-minded arts organizations, as well as provide us with an example for conducting needs assessments in our affiliate network. I worked with Stephen through-out the process, but I'll let him provide the key findings since he was the Principal Investigator.

SY: Thank you, Don. This needs assessment was conducted to ascertain primary obstacles to and opportunities for providing quality arts education to students with special needs in New York City public schools. The chief purpose was to help practitioners and policy makers - in the school and arts communities in New York City - to gain a deeper understanding of the field and its complexities, as well as provoke reflection and action. Professional development (PD) for teaching artists (TA) working with this population was considered at length. The majority of teaching artists who participated in a focus group and interviews called their primary means of training "trial by fire". Over two-thirds of a broader survey of teaching artists also cited "trial by fire" as their initial experience in learning to work with students with special needs. 33% of the survey respondents said that they have never received professional development regarding these students. The other 66% who had undergone such training, did so as noted below:

click here to view table.pdf

To say this another way, in thirteen key professional development areas, slightly more than 40% of teaching artist respondents currently working with students with special needs in New York City public school classrooms - self-contained and/or inclusion - have received professional development in one domain - "special needs classifications", and anywhere from 33% down to 11% have received training in the other twelve.

This is in the process of changing. More and more art organizations are recognizing the need to provide training to their TA's in working with populations with special needs. In fact, 78.6% of arts administrator survey respondents said their organizations offer such PD. However, the majority of arts administrators interviewed and who participated in the focus group also spoke of the need to go further in their professional development efforts.

RK: Did you find anything that surprised you?

SY: Absolutely. The biggest surprise was in discovering many contributions that inadvertently undermined the arts education opportunities for students with special needs, and that such contributions were sometimes made by those most supportive of the arts. An example of an inadvertent consequence is the practice of "clumping" classes for arts residencies. There are two major forms of clumping: (1) two or more self-contained classes are combined; or (2) a self-contained class and a general education class are combined.

While arts organization administrators by and large felt the practice was not a good one, most did not want to jeopardize school partnerships by turning down a request to combine classes. Schools also wanted to get the most bang for their buck in residencies and were unable to justify spending the same amount of money on a class of, say, twelve students as on a class more than twice that size. As you know, self-contained special education class sizes can be considerably smaller than general education ones for sound educational reasons.

For some populations, notably those on the Autism spectrum, practices like class clumping can bring new and unfamiliar circumstances to young people who require consistency, routine, and ease-in-transition. For others, especially those with severe behavioral issues, combining classes could prove volatile. In the end, the students, nor the arts organizations are served well. Clumping inadvertently diminishes the quality of arts education by forcing an instructional environment that is known to be pedagogically unviable for and unsuitable to students with special needs.

RK: What did the assessment indicate about teaching artists, classroom teachers, and certified arts specialists?

SY: As I mentioned earlier, there is a greater need for professional development as more students are being diagnosed as special needs, and more students with special needs are being moved into increasingly inclusive settings. Consequently more classroom teachers, arts specialists, and TA's are working with this population. These educators recognize the need to build capacity and knowledge and identified their professional development needs in response to this study:

Arts Specialists:

• Adaptive curriculum planning, especially for inclusive settings

• Adaptation of the NYC Blueprint for students with special needs

• Special needs classifications

• Documentation/Evidence gathering and how to best use it to teach others - especially classroom teachers, administrators and parents - the value of arts in education

Classroom Teachers:

• Special needs classifications

• Disability-specific instructional approaches

• How to better work with para-professionals

• Arts assessment

• Curriculum design

Teaching Artists:

• Understanding special needs classifications

• Targeting achievable outcomes and planning/implementing appropriate curriculum

• Differentiating instruction

• More professional development in general

RK: What are some new structures, resources, approaches, etc., that you would like to see developed?

SY: Ongoing Exchange and Dialogue: However much professional development is called for, designed and offered; however much pertinent and valuable resources are brought together and made available; however much suggestions made in the study are implemented, the value of open conversation, sharing, and reflection among peers and across stakeholder groups in building and deepening knowledge, understanding, and capacity cannot be overstated.

Providing venues for such dialogue can greatly contribute to increasing the quality of arts education offered to students with special needs in New York City public schools. The study calls for a new kind of inclusion - in building knowledge and capacity, preparing, implementing, structuring, partnering. Throughout the needs assessment, I was struck by how what one constituency did not know another did or could help profoundly with and - not surprisingly - how much people working in this field want to help others.

Professional Development for Para-professionals: Arts specialists, classroom teachers, teaching artists, school and arts administrators often spoke of the value of having para-professionals assisting in classrooms:

• The ability to work in small groups

• The ability to provide more individualized instruction as needed

• The ability to draw off the often-deep knowledge that some para-professionals have of students.

However, the quantity and quality of para-professional assistance was often called into question. This was largely due to lack of their experience and knowledge regarding arts education. Offering para-professionals professional development in arts education for students with special needs that includes a mentoring component is a strong and viable entry point. It is also a timely one.

The NYC Department of Education and the New York State Education Department recently increased the required number of college credits newly hired, full-time para-professionals must earn by the end of their third year of service. This is generally seen as part of an effort to professionalize the position of paraprofessional. If PD for arts education could be provided for course credit, all the better.

Looking at Student Work: One way of further connecting teaching artists, arts specialists, and classroom teachers- and possibly, of linking their collaborations with whole school effort - is providing opportunities to collaboratively examine samples of student work. Looking at student work can play a key role in deepening knowledge about student learning and the role of the arts in special education. Engagement with the arts can reveal abilities and, sometimes, hitherto unknown capacities. For example, highly non-verbal students have been known to break into spontaneous speech during improvisation, or to sing fluidly to music. This is valuable information not just for classroom teachers and arts specialists, but for speech therapists. Similarly, physical and occupational therapists may benefit from watching motor activities of students engaged in dance, creative movement and/or visual arts.

Of course, to do this requires building the capacity of these constituencies in looking at the art work of special needs students. This presents an entry point for those organizations who might offer such training and an important opportunity for the field of arts in special education. Providing such professional development could well draw jointly upon the resources and expertise of NYC DOE and outside cultural organizations.

RK: What else would you like to add?

SY: The field of arts in special education is tremendously rich, greater than any one of its stakeholder perspectives or needs, greater than all of its stakeholder parts. If it is to meaningfully move forward and deepen the quality of arts education for special needs learners, there must be room at the table for all these voices. It is necessary for these groups to engage in ongoing dialogue, to seriously address the field's differences from general education arts education, to follow the lead of its own needs and requirements, and to understand it has much to offer teaching and learning - not only in special education, but to education in general.

DG: I want to thank Stephen for sharing the key findings of the needs assessment study, and note that when Stephen is not conducting needs assessments, he is an instructional coach for our Communities of Practice and Teaching Artist Fellowship programs. As a coach, he facilitates discussions around examining student work and fostering inclusive arts instruction. In other words, he provides teaching artists with feedback on how to include more students, remove barriers to the curriculum, and improve their arts instruction for a range of students, which by the way, are some of the general professional development needs and entry points identified in the study.

RK: What else are you both working on?

SY: I'm also evaluating numerous arts education programs, and am the co-chair of The Arts in Special Education Consortium, a NYC-based organization dedicated to bringing together stakeholders in the field to share ideas, build capacity, understanding and sense of value.

DG: VSA arts is exploring the relationships between inclusive arts teaching and learning and Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Ideas, tools, and processes that we have introduced in our conferences, professional development institutes, and online professional learning communities, are now supporting teaching artists in our program and affiliate networks to understand and apply the Universal Design for Learning guidelines to their arts residencies (i.e., providing multiple, flexible options for representing content, engaging students, and demonstrating knowledge and skills). Over the next year, VSA arts will be sharing various examples and case studies of what inclusive arts teaching and learning looks like in practice. Most of our rich examples have come from our professional learning community teams. We hope to add a team from our NYC or New York State affiliate next year to contribute to our inquiry into inclusive arts education!

Click Here to View Presentation of Report--Making Room At The Table.pdf

About Stephen Yaffe and Don Glass

Stephen Yaffe, is an arts and education consultant. He has evaluated

numerous school/arts partnerships - special and general education - as well as conducted many needs assessments, including those of the New York State Council on the Arts Arts-in-Education program, the Pittsburgh Fund for Arts Education and many New York City arts organizations.

His professional development work has been praised by the Director of Education Programs for the Corporation of Public Broadcasting as being, "brave, visionary, smart". He is currently the VSA Teaching Artists Fellows coach, mentoring a select group of teaching artists working in Iowa, Michigan, Nebraska, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Ghana.

Don Glass, Ph.D, is the Director of Outcomes and Evaluation at

VSA arts in Washington, DC. His work uses evaluation

strategies as ongoing teacher professional development and

capacity-building for partnerships programs with arts and cultural

organizations and public schools. His work at VSA arts focuses on

building evaluation capacity to gather, use, and share valuable

knowledge about inclusive arts teaching and learning.

DC. His work uses evaluation

strategies as ongoing teacher professional development and

capacity-building for partnerships programs with arts and cultural

organizations and public schools. His work at VSA arts focuses on

building evaluation capacity to gather, use, and share valuable

knowledge about inclusive arts teaching and learning.

His professional development work has been praised by the Director of Education Programs for the Corporation of Public Broadcasting as being, "brave, visionary, smart". He is currently the VSA Teaching Artists Fellows coach, mentoring a select group of teaching artists working in Iowa, Michigan, Nebraska, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Ghana.

Don Glass, Ph.D, is the Director of Outcomes and Evaluation at

VSA arts in Washington,

DC. His work uses evaluation

strategies as ongoing teacher professional development and

capacity-building for partnerships programs with arts and cultural

organizations and public schools. His work at VSA arts focuses on

building evaluation capacity to gather, use, and share valuable

knowledge about inclusive arts teaching and learning.

DC. His work uses evaluation

strategies as ongoing teacher professional development and

capacity-building for partnerships programs with arts and cultural

organizations and public schools. His work at VSA arts focuses on

building evaluation capacity to gather, use, and share valuable

knowledge about inclusive arts teaching and learning.