The revived Dance Theatre of Harlem performs at Jacob’s Pillow, June 19 through 23.

If a repertory company starts its program with a performance of George Balanchine’s Agon, where can it possibly go from there? Higher? Don’t make me laugh. But whatever follows, you can get a jolt of almost electric pleasure when Dance Theatre of Harlem begins its performance in Jacob’s Pillow’s Ted Shawn Theater by presenting an immaculately danced, sensitively directed performance of the 1957 Balanchine-Stravinsky masterwork.

DTH’s week at the 81-year-old dance festival is a homecoming of sorts. Many of us got our first look at the company at the Pillow. It was the summer of 1970, and the year before, in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, ex-New York City Ballet principal dancer Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook had founded a ballet school in Harlem that reached out to black children. And not only a school, but a company. In that assembly of African American classical dancers on the Jacob’s Pillow stage was a beautiful, skinny girl with a modest afro who looked even younger than her 20 years.

That girl, Virginia Johson—whom you might remember best as the willowy heroine of DTH’s 1984 Creole Giselle, and/or as the founding editor-in-chief of Pointe Magazine—is now the artistic director of the company. In 2004, after years of artistic success and worldwide touring, DTH was disbanded; funding problems had led to a massive debt. The company reappeared this year with a smaller, racially diverse ensemble of 18. Its New York City season in April was celebrated as a resurrection. Laveen Naidu, another former company dancer—one with Harvard Business School creds—has served as Executive Director since DTH folded, and, with Johnson, masterminded the plan that re-launched the performing group.

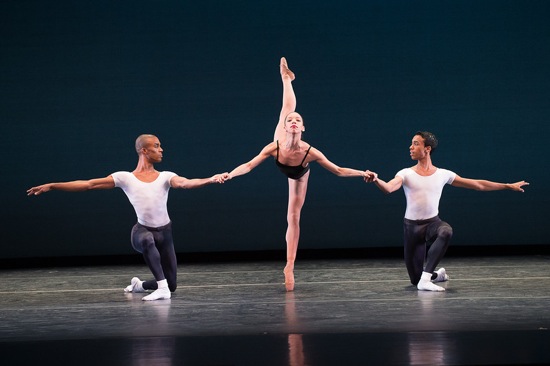

The second Pas de Trois from Balanchine’s Agon. L to R: Anthony Savoy, Chrystyn Fentroy, and Francis Lawrence. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Agon has particular resonance for the company. Balanchine created its reserved, but powerfully sensual duet for Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams, (The fact that one of these principal dancers in the New York City Ballet was white and the other black startled many in the 1957 audience.)

The Ted Shawn’s stage isn’t as big as the one at New York’s City Center, where Balanchine and Stravinsky premiered Agon. But do the dancers hold back or make the stage appear too small? Not until they have to maneuver to take their bows do you get even a hint that this is a smaller stage than the ones on which NYCB performs the ballet now. The spaciousness of Agon! Cool, crisp air surrounds it. And the dancers in their dark blue-gray and white practice clothes must combine large-scale gesture with stiletto precision. The four male athletes who open it with canonic moves stretch their limbs into space and swing themselves off balance to lunge out farther than you’d have thought reasonable. When eight women join them to complete the cast, legs flash in all directions like spears. Three squads of four? No problem. And Richard Tanner, who staged the ballet, evidently hasn’t allowed these dancers to forget that in ancient Greek, “agon” means a contest; their focus on one another and their intensity subtly underscore that atmosphere.

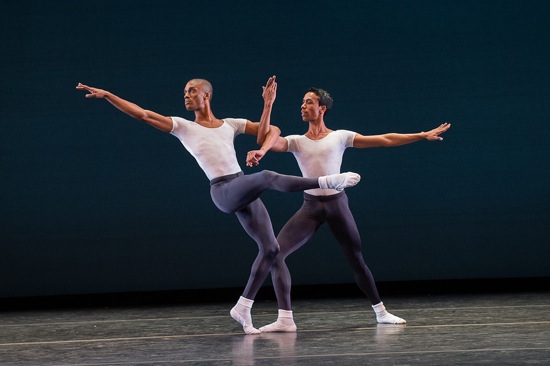

Anthony Savoy and Francis Lawrence in the duet from Agon‘s “Second Pas de Trois.” Photo: Christopher Duggan

Just as Stravinsky referred to Baroque court dance in his exquisitely orchestrated fusion of diatonic procedures with twelve-tone ones, so Balanchine intermittently created images of elegance and decorum, even as he twisted and pushed movements askew and enlarged the classical vocabulary. Ashley Murphy, Jenelle Figgins, and Taurean Green dance the first Pas de Trois with aplomb, and Francis Lawrence and Anthony Savoy perform the male duet in the second Pas de Trois with the scissoring vigor it requires. This lightning-fast “Bransle Simple” pits the two against each other in such a close canon that the second man to start always seems about to catch his opponent. Chrystyn Fentroy imbues the trio’s solo with a soft sureness, making the movements breathe.

The Pas de Deux is danced by Gabrielle Salvatto and Fredrick Davis—he warmly attentive, she supple, feline, and responsive within the sharply looped and angled maneuvers in the choreography. Here the term “agon” might be translated as struggle, yet any effort is downplayed. Stravinsky’s music makes you feel the hot stretch of the woman’s muscles as her partner courteously and skillfully assists her, molding her into uncanny positions that court dancers of yore encountered only in their erotic fantasies.

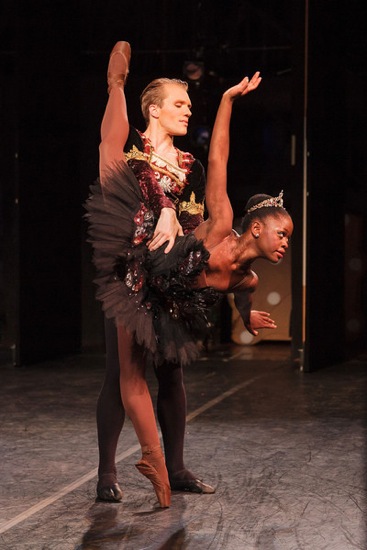

After that opener, DTH offers a look at the classicism that Balanchine and Stravinsky unsettled. There’s nothing off-balance in Tchaikovsky’s beautiful music for Swan Lake, and in Marius Petipa’s choreography pointework suggests stability, control, and power. The pas de deux from Act III was staged for DHT by Anna Marie Holmes via Nicholas Sergeyev, who learned Petipa’s ballets in Russia toward the end of the choreographer’s life. In this duet, the Swan Queen’s evil double must lure Prince Siegfried to his downfall, and when Michaela DePrince danced the role at the Pillow’s opening Gala, I thought that she was only trying to wow him with her rock-solid technique. But this vastly gifted dancer (born in Sierra Leone and raised in the U.S. from an early age) came alive during DTH’s first night. Now we see how a balance on one toe can become a flirtatious taunt, a kind of purr, and how the ballerina’s every move is aimed to deceive the prince into thinking her far sweeter than she is. No wonder DePrince’s partner (the excellent Samuel Wilson) keeps pressing his hands to his heart and sighing in pleasure.

Those 32 fouettées that Odile whips off in the coda? DePrince aces that demonstration of killer virtuosity, and—a fine touch—she occasionally decorates one of the many revolutions with a little birdlike flap of her arms, as if to say to the hero, “really, I’m just the sweet little enchanted swan you love; I’m only wearing black and diamonds because I couldn’t find my white tutu.” He falls for it big time.

Gabrielle Salvatto and Fredrick Davis of DTH in Alivin Ailey’s The Lark Ascending. Photo:

Christopher Duggan

Alvin Ailey’s 1972 The Lark Ascending marks one of his first embraces of lyricism and balleticism. Its swirling patterns provide a contrast to the other pieces on the program. DTH’s women perform it in pointe shoes, which works well enough, although it’s not a compelling element of the choreography; the dancers just step up onto a toe when it seems appropriate—say upon moving into an arabesque. Ailey set the work to Ralph Vaughan Williams’s lovely Romance for Violin and Orchestra, but it’s more as if he set it beside the music, heeding its overall mood but not the shape of its phrases. (It doesn’t help that the recording is played at such a volume —or was on opening night—that it loses some of its windswept romanticism.)

Thomas F. DeFrantz’s admirable book Dancing Revelations:Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture notes that the principal female dancer personifies the lark that takes flight—a symbol of the woman’s awakening to love; her partner is the hunter as well as the pursuing lover. Another couple (Green and Figgins) echoes their relationship, as do four other pairs, the woman in filmy, pastel dresses by Bea Feitler. I don’t quite catch that hunter-prey imagery in the sensitive staging by a former “lark,” the beautiful Eizabeth Roxas-Dobrish; maybe I never did.

Salvatto is as excellent in this as she is in Agon. Her joyful buoyancy in the choreography’s leaps and spins and fluid, ground-covering passages animates what seems like a very long, rambling solo that is strangely thin in terms of movement material. Davis is her ardent partner, and Green follows Figgins with equal devotion.

No one could accuse John Alleyne of making dances that have a loose weave. In Far But Close, Alleyne—who, for a number of years, was the artistic director of Canada’s Ballet BC—works the dancers through an intricate, rarely stopping body language that mingles ballet steps with knottier moves. When Jehbreal Jackson coils and uncoils his limbs, dipping to the floor, and rising in some kind of marvelously complicated conversation with his own body, you can understand why Stephanie Rae Williams stands watching him for so long. They are not the only splendid performers in Far But Close. Occasionally, Murphy and Da’ Von Doane stand shoulder-to-shoulder with them, telling us. . .what? That the four are friends? That the second two are the others’ alter egos? The a man and woman who periodically talk to each other in a recorded text by Daniel Beaty sometimes use Black English Vernacular, sometimes not; sometimes they speak in rhymed poetry, sometimes in blunt prose.

Oh that text! It intermittently interrupts Daniel Bernard Roumain’s very expressive music. The first line, “Pretty little black girl. . . ,” introduces a flirtatious pick-up on a subway, moves onto casual sex (don’t bring in “that love shit,” the woman says). But, along the way, love does enter, along with allusions to the man being in prison and questions like “Would you believe in love again?” There’s even a brief, hard-to-assimilate reference to the Middle Passage and bodies accustomed to being packed together.

Beaty’s words effectively set place and mood, but it’s heavy, complicated freight for the often very interesting dancing——to bear. And the choreography goes its own way, only occasionally and very obliquely relating to what we hear.

L to R: Francis Lawrence, Da’ Von Doan, Chrystyn Fentroy, and Dustin James in Robert Garland’s Return. Photo: Matthew Murphy

A program like this needs a closing number, and choreographer Robert Garland (who danced with DTH for 13 years) has couched his 1999 Return in what he calls “post-modern urban neoclassicism.” Translate that as “almost anything goes” and “be prepared: ballet dancers getting down.” The music is great: James Brown opens with “Popcorn,” and Aretha Franklin follows with “Baby, Baby, Baby;” he sings three songs, she two). Yes, it’s a party dance, with the whole company eventually on view (hello there, Ingrid Silva, Alexandra Jacob, Emiko Flanagan, Lindsey Pitts, Dustin James). But I’ll bet you never saw a bunch of strutting, hip-swinging women and cool guys segue into five-part counterpoint.

In the closing “Superbad,” led by Green (a Pillow alum), brief, ebullient solos and show-off stunts emerge from the crowd. Garland must have tailored it to DTH’s individuals. A mean back flip, Savoy!

From what I hear and intuit, the dancers have come a distance since DTH’s April performances in New York in terms of confidence and clarity. They have technique to burn; they can run with it. I hope Johnson builds a new repertory wisely—one with choreography that will challenge them in every way.

That Ms. Jowitt is some of the most eloquent, compelling writing about “Agon” that I have ever read, and I have read a lot of it. I would add that I have had a soft spot in my heart for DTH for decades, and for Virginia Johnson as well, a graceful editor at Pointe Magazine, a glorious Creole Giselle. DTH toured Portland many times in the Eighties and Nineties; the late Elena Carter relocated here in the early Eighties and was my daughter’s first ballet teacher; the late Lowell Smith taught at Jefferson High School, which is all by way of saying members of that company had an enormous impact on this community. Thank you for this lovely review.