Stephen Petronio Company at the Joyce Theater, April 30 through May 5, 2013

Dancers in Stephen Petronio’s Like Lazarus Did (LLD 4/30), Emily Stone center. Photo: David Rosenberg

Over a hundred black-clad members of the Young People’s Chorus of New York City form a V around the corner of the Joyce Theater—some on 19th Street, some on 8th Avenue; over a hundred pairs of eyes focus on composer Son Lux (aka Ryan Lott), who, shielded by a parasol, is playing guitar alongside trumpeter C.J. Camerieri and violinist Rob Moose. “Come out!” sing the kids in sweet harmony to a burgeoning crowd of spectators—most of whom have come to the Joyce to see Stephen Petronio’s world premiere, Like Lazarus Did (LLD 4/30). “Come out!” Their voices are quiet, but urgent.

Meanings float around above the pavement we share. “Come out” in order to proclaim you’re gay. Come out from the darkness into the light—whether that darkness is death, ignorance, or the womb. Emerge from the sepulcher, Jesus! You, too, Lazarus! Phoenix, rise up from those ashes! “Come out!” is also what I’ve been saying to the place in the grass where daffodils should be pushing up to confirm Spring.

It may not be entirely coincidental that we’re seeing this glorious new work of Petronio’s in the year that honors the 100th anniversary of the Stravinsky-Nijinsky ballet The Rite of Spring; although the Chosen Virgin danced herself to death, she was responsible for another kind of renascence: she made the crops grow.

Petronio wants us to experience LLD—at least in part—as an installation. We must enter the theater by climbing stairs and descending the left aisle to our seats along a pathway of light. In addition to handing out programs, ushers give us little cards that query in gothic letters, “Should I look among the living/ Should I look among the dead/ If I’m searching for you?” This is a pretty deep question. The choreographer lies supine at the edge of the stage; he’s dressed in a white shirt and black suit, but he’s barefoot. The red velvet front curtain, lit to jewel-like splendor by Ken Tabachnick, is draped up at the bottom and its hem sits just a foot or so above his head. High above the right side of the audience hangs the kind of stretcher used for lifting the injured or dead to a waiting helicopter. It appears to contain a mossy bed, on which its designer, artist Janine Antoni, lies motionless. Above her are suspended plaster replicas of dancerly legs, skeleton legs, heads, arms, and more. Who will rise? Who will die?

A large cadre of the young singers enters to fill the left side of the U-shaped balcony; the chorus’s founder-director, Francisco J. Nuñez, conducts them from the other end of the balcony, across the house. The rest of the chorus members fill both aisles, framing us, containing us. They echo words that Son Lux calls out, such as “I want to die like Lazarus did.” Meaning, perhaps, that expiring not long before Jesus walks in, needing a miracle, is a good way to go. Many of the words that infiltrate Son Lux’s eerily beautiful score (played by Camerieri, Moose, and the composer on piano, percussion, and electronics) were drawn from slave songs of the early 19th century, when the hope of resurrection made the labor easier to bear.

Refresh, revive, resuscitate, reincarnate, make new. These processes have clearly been on Petronio’s mind. For the opening scene of LLD, Petronio has recycled and refurbished the white costumes that Tara Subkoff designed for his 2003 Underland. He has also reconstructed solos made for other company dancers in years past and refurbished them for individuals in the current group. Compositional devices like accumulation and retrograde come into play; perhaps he first became expert at these during his years of dancing with Trisha Brown.

Not all of this is visible in the dance of course. In his program note, Petronio refers to “our dancing flux,” and anyone watching the maelstroms he creates on stage, doesn’t have time to think about the process behind the work. But although he’s a voluble choreographer, he’s not a facile one, and although his dancers are virtuosos, they dance like celebrants in a carefully designed rite, never holding a pose so you can admire its beauty and as apparently effortless as we imagine angels to be.

Petronio’s works have nothing in common with those of Isadora Duncan, but both choreographers seem to conceive of the body as a kind of holy machine, in touch with the earth’s processes. A powerful motor drives the whirling arms; slashing legs; mobile hips; and rippling, canting torsos. Amid the spins; the leaps; and the explosive, straight-up jumps that Petronio creates, you can divine a compulsion like the one Dylan Thomas hymns in his poem “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower.” You may find the choreography of LLD relentless, with the dancers as intrepid, complicit, untiring heroes, but there’s something exalted, white-hot about it.

The beginning of the dance asserts order. The singers in the aisles have left. So has Petronio. The three musicians have gathered in a corner; the conductor and the chorus members in the balcony are on their feet. Nine of the company’s ten members stand onstage, divided into three trios. You see every action in triplicate. Over and over, one person from each group dances toward the audience and then back to place, while those still at the back continue their interactions. The phrase seems to grow as the process continues; I begin to think each set of three is echoing what’s been established and adding something new. Counterpoint develops.

Joshua Green and Natalie Mackessy (center), Davalois Fearon (L), Barrington Hinds (background).

Photo: David Rosenberg

But soon Petronio develops an idea that’s particular to this dance. Intermittently, throughout it, people yield to weakness and collapse or lie down. Others catch them, cradle them, lift them, or pull them to their feet and into the ongoing tide of dancing. “These are my Father’s children,” sing the young voices. Joshua Green, Gino Grenek, and Joshua Tuason, who’ve been carefully laid out by three others, revive and leave as Emily Stone and Natalie Mackessy dance close together, each in her own way. Small Mackessy collapses onto tall Stone, just as Davalois Fearon makes her first entrance. (She, Barrington Hinds, Jaqlin Medlock, and Julian De Leon are the first to appear wearing minimal black costumes—sometimes veiled in brown—by H. Petal; intricately cut and strapped, they bare much of the performers’ mobile backs.) The smoke at the rear of the stage seems a little denser. “Allelujah!” call out the singers. A little later, to a thudding drum and cymbals, Nicholas Sciscione, Tuason, and Green treat Davalois as a colleague who needs lifting into the light.

L-R: Nicholas Sciscione, Joshua Tuason, and Joshua Green support Davalois Fearon. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The music collaborates wonderfully with this constant process of leaving and arriving, of succumbing and recovering. The disparate voices of piano, trumpet, and violin (along with Son Lux’s singing) herald what needs to be heralded, sigh or shiver when appropriate, and jangle amid stormy electronic weather. Heavy piano chords sound when the dancers enter hand in hand, like a chain gang of diverse individuals. When the four women dance in unison, we hear words from Sojourner Truth’s famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” And just as stillness occasionally vies with movement, silence pits the music.

There’s an enigmatic passage when Tuason stands alone, his back to the audience, in front of a white ribbon or rope that has descended from above. Lit from below, he undulates slowly, muscularly, gazing at it. Climbing doesn’t seem to be an option. And when that scene is over, the lighting turns rosy, and the others re-enter in new costumes that include red kilts for the men. A drum joins in. The dancers cluster and fall and pass through in groups. The sung words turn apocalyptic: “The moon will turn to mud. The world will be on fire. The stars will fall. . .”

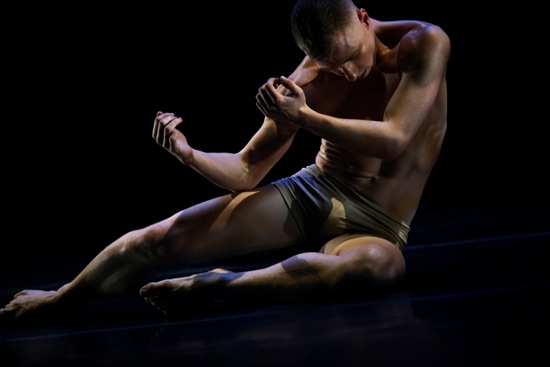

Nicholas Sciscione reborn in the final moments of Like Lazarus Did (LLD 4/30). Photo Julieta Cervantes

There have been solos before: Grenek writhing on the floor, Green smoothly pulling and twisting himself through invisible holes in the space around him. But the final solo, performed by Sciscione, sends an unambiguous message of rebirth. He’s wearing only flesh-colored briefs, turning in circles while lying on the floor, rolling, twisting, pushing his butt up the way babies do, struggling as if on a difficult, pre-ordained journey. The chorus now slides into counterpoint. The male voices sing a variant of the words on the card: “Should I look among the living? Should I look among the dead?” The women echo Son Lux in a lullaby: “Sweet dreams; shut your eyes and dream.” Finally Sciscione gets to his feet; he’s taking teetering, tiptoe steps toward the back of the stage as the lights go out.

Afterward, I climb up to the side of the balcony to get a better look at Antoni as she lies in her cradle. Until now, I’ve only been able to discern her motionless profile. Almost everyone has left the theater. Her eyelids are fluttering.