Robert Swinston (front) and Germaul Barnes in The Men Dancers: From the Horse’s Mouth (dress rehearsal). Photo: Taylor Crichton

Eighty years ago, when Ted Shawn assembled the all-male company that toured the U.S. with him during the 1930s, he aimed to eradicate the notion that dancing was for sissies (the polite, if bullying term for boys whose masculinity was in doubt). Almost all of those who joined Shawn’s Men Dancers were graduates of Springfield College’s Physical Education Department, and he toughened them further in those Depression years by having them hammer, hew, and dig to make the Massachusetts farm known as Jacob’s Pillow into their headquarters. Judging by newspaper reviews of the group’s tours, Shawn’s messianic fervor and the guys’ displays of well-muscled torsos and athletic zest achieved his goal.

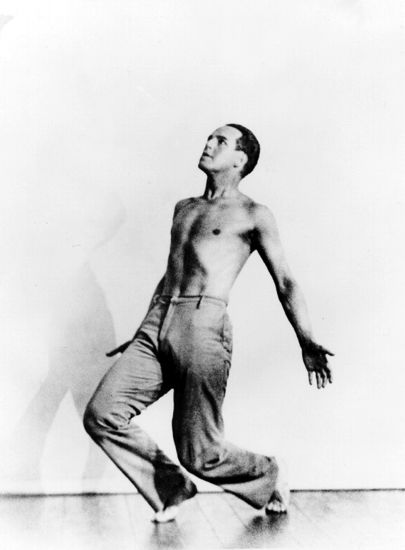

Black-and-white films show them leaping about an outdoor wooden platform; they were good at bursting into the air and walloping it with their arms—without the finesse that would have perhaps branded them as effeminate, but with an orderliness that could be identified as soldierly. Shawn sneaked in lyricism and talked about ancient Greek athletes. Most of the men were drafted during World II, and afterward, few of them returned to dance. For the others, their performing life had been rewarding during rough economic times, but they packed it away along with the rest of their boyhood.

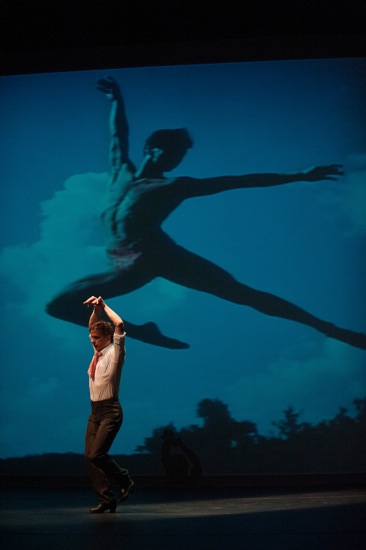

A clip of Shawn’s Kinetic Molpai appears on the wall of the Pillow’s Doris Duke Studio Theater to open The Men Dancers: From the Horse’s Mouth, an all-male version of the structured improvisation that Tina Croll and James Cunningham have been presenting with various motley casts since 1998. Anyone watching the show in Becket, Massachusetts (July 11-14) might have wondered what Shawn and his hale young men moving in exalted unison would have thought of the 25 dancers who performed From the Horse’s Mouth in honor of the Pillow’s 80th anniversary. (Glimpse Shawn’s men at http://www.danceinteractive.jacobspillow.org/dance/ted-shawns-men-dancers.)

These performers (I saw the opening-night cast) are tall, short, slender, beefy, young, mature, nimble, slghtly stiff. They speak ballet, tap, flamenco, jazz, modern dance, and Bharata Natyam. They are Broadway stars, choreographers, teachers, and artistic directors of companies. A few have had long careers; some are just getting started on theirs. They represent a rainbow of races.

Standard gender images are up for grabs. Emanuel Abruzzo performs an elegant solo on pointe and later returns in shirt and trousers for more down-to-earth stuff. Some who’re gay let us know that (Chad Michael Hall gets an enthusiastic hand when he announces that he and his partner are planning their wedding). During intermittent diagonal processions, they parade in favorite costumes (like Arthur Aviles’s circular-skirted red velvet dress or Germaul Barnes’s jockstrap of tiny white shells plus a gorgeous glittery train and) or dream ones. And they perform bathed in Carol Mullins’s fine lighting, in front of occasional slide shows of the many, many male dancers who have graced the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival over the years. What do the onstage men have in common? Dancing is their life. Gus Solomons jr (no youngster and recovering from a back operation) currently walks with a cane. So what? Onstage, he’s a king.

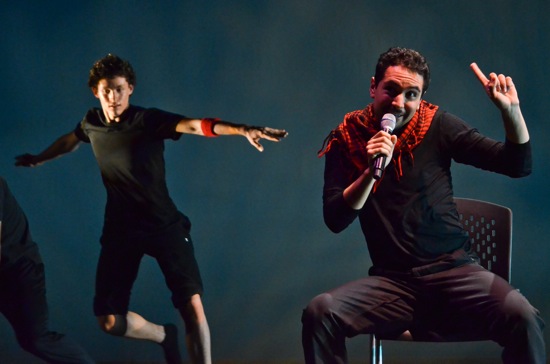

The structure of From The Horse’s Mouth promotes kinship and offers unexpected delights. Idiosyncratically outfitted in black with touches of red, each performer tells a short story; each one composes a 16-count movement phrase in place and varies it according to instructions he draws from a pile of cards; each creates a traveling phrase and follows the path mapped out on a card from another pile. These three activities, in rotation, all happen at the same time. A fourth person is free to improvise in response to what he observes the others doing. This may sound rigid, but as a veteran of mixed-gender renditions of the piece, I know that a relieving bit of elasticity respects some participants’ limitations and lets others run moderately wild.

Their stories are inspiring, sobering, hilarious, deeply affecting. Many of the performers tell of an incident that started them off on their careers. They mention mentors. Cartier Williams had to free himself from a demonic one. Arthur Mitchell, founder of Dance Theater of Harlem, reminisces about a more generous one: George Balanchine (while in slides and film clips, the splendid young Mitchell dances his roles with the New York City Ballet). Trent Kowalik, 17, relives the long audition process that led him to being one of the boy leads in both the London and New York productions of Billy Elliott. Lar Lubovich recalls auditioning to get into Juilliard, while behind him, the very young Lar performs, in grainy black-and-white, the very solo (his own composition) that impressed the judges.

(L to R) Chad Michael Hall, Arthur Mitchell, and Arthur Aviles. Behind them: Mitchell and Suzanne Farrell in Balanchine’s Agon. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Hari Krishnan, director of Toronto’s inDance, provides a witty talking-demonstrating explication of the many evictions he endured from apartments as the result of his foot-stamping Bharata Natyam practice. John Heginbotham interpolates recipe instructions into his very funny account of the day when 2011’s Hurricane Irene forced the cancelling of the Mark Morris Dance Group’s final Jacob’s Pillow performance (the dancers divided into two teams and had a wildly imaginative cook-off, which ended with them running drunkenly and nakedly out to dance in the rain). Aviles sings, in a mélange of Spanish and English, his indescribable merger of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” and the preparation of a favorite Latino treat.

I’m sure that by the last performance—even with newcomers (such as Charles Askegard, former New York City Ballet principal dancer, and master tap artist Jason Samuels Smith) feeding in—the backstage and onstage camaraderie among the men resulted in ever more daring interactions. But on opening night, it was grand to see, for example, Steven Melendez, who’d been doing elegant ballet port de bras, mesh with Hall into a duet of slow lifts and supports. Or lanky Kowalik trying to copy the tough, tight, jerky hip action of Yusaku Komori. Or Heginbotham echoing Bruno Argenta’s Spanish arm gestures. Todd Allen and Cunningham embrace; Heginbotham cuts in politely, as if at a ballroom event, and hugs Cunningham. Dancers with little in common except for their commitment to dancing respect, investigate, and enjoy one another’s moves.

Bruno Argenta shows his heelwork beneath long-ago NYCB dancer Nicholas Magallanes assailing the Berkshire sky. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Other striking individuals that night: Norton Owen, Chet Walker, Miguel Anaya, Christopher Caines, Jamal Rashann Callender, and Joshua Beamish.

There’s really no point in wondering what men dancers eight decades ago would have thought of this smart, greatly gifted crew of professionals. What might have thrilled them though was the audience’s hearty, happy applause for all kinds of dancing, all kinds of men.

Wonderful report! Conjures up so many images, and after-images, so many layers — so funny, so touching, so poignant. Is that Barton Moomaw in the stag-leap on the screen behind behind Argenta? If it’s not I saw him anyway in the tale of building hte Pillow. So much had to be hidden, but so much was revealed.

Paul Parish’s message reminded me that I was able to update my original post with information about that leaping dancer. Jacob’s Pillow notified me that it was Nicholas Magallanes, founding member of New York City Ballet. Also, in my update, I corrected Stephen Melendez’s first name.

Dear Deborah,

Thank you for the beautiful article titled “Dancing Men: Then and Now.” I truly enjoyed it and your writing definitely helped me see the dance. I remember performing in “From The Horse’s Mouth” in NYC and in LA and enjoyed being with all the other dancers during rehearsal and performance! Hope that you are doing well, and again thank you!

All the best,

Jeff Slayton