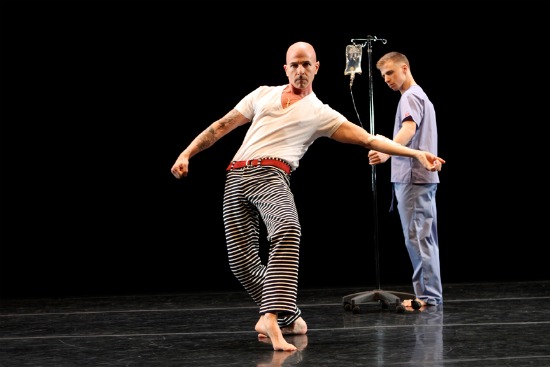

Davalois Fearon, Emily Stone (center back), Natalie McKessy, and men in Stephen Petronio's The Architecture of Loss. Photo: Julie Lemberger.

Stephen Petronio’s melancholy, disturbingly beautiful new Architecture of Loss is, I’m pretty sure, fraught with more stillness and more silence than any of the works he’s made over the last couple of decades. The word “architecture” in the title tells us that he’s not trying to show us mourning as a response to loss; he’s showing us loss as absence and the evanescence of supporting structures.

Except for visual designer Ken Tabachnik and Ravi Rajan, who created the slides, Petronio’s collaborators are all Icelanders: composer Valgeir Sigurdsson, costume designer Gudrun & Gudrun, and artist Rannvá Kunoy, whose cloudy paintings are projected onto three large screens that hang at the back of the Joyce Theater’s stage. The very first—and loveliest—images are in soft gray strokes and smudges that could have been made by pastels. In them you can imagine you see water, wind, bridges, bluffs—all swathed in fog.

The music—played live by Nadia Sirota (viola), Shazhad Ismaily (percussion, bass guitar, et al), and the composer (piano, electronics, and more), with Nico Muhly on recorded piano—can sound chill and eerie: there’s singing, echoing, rasping, crackling. At times, the piano emits single, spaced-out notes that sound like water dripping resoundingly on ice in a momentary thaw. The dancers wear woven attire, some of it loosely cut, that hints at fishnet.

A cold atmosphere, then. It feels the way a room feels when someone dear to you has gone away for a long time. The landscape of the stage keeps reconfiguring itself, as if, after the disappearance of one or more of the dancers, it has to re-calibrate itself. People replace one another in unfinished business. Three plus two equals five, minus one equals four. Sometimes one or two of the screens at the back go blank; the single deep pink or yellow smudges that take over from the more complex grayness come and go.

The movement, as in most of Petronio’s choreography, amplifies and disorders the dancers’ bodies in space. They rarely place their gestures. They swing one straight leg in a semi-circle, say, and let that impetus pull the rest of their body into new directions. They wheel their arms and lash the air. They make you aware of jutting elbows. Impulses arise in their spines and ripple out; a big assertive gesture may leave its aftermath—perhaps a head, slow to follow, suddenly seems only loosely anchored to the neck that supports it. If the performers didn’t attack so incisively, they might make you think of rag dolls flung by unseen hands. Instead, think whirlwinds.

In The Architecture of Loss, however, these superlative performers spend intermittent time standing like a frozen forest, while others dance around and among them. Here are their names: Julian De Leon, Davalois Fearon, Joshua Green, Gino Grenek, Barrington Hinds, Natalie MacKessy, Jaqlin Medlock, Nicolas Sciscione, Emily Stone, Joshua Tuason, Amanda Wells.

Encounters are brief. People form tableaux, collapse, lie still. In some of the meetings, one person leans against another. This act acquires the most emotional resonance in a duet for Green and Wells. You feel the effort and the daring when Wells leans out at a precarious slant, bracing herself on whatever part of his body Green offers her. You see the muscles in her back engage, feel the stress in her arm, while she holds the position until she slowly crumples. Green lifts her, presses her around himself, but in the end he deposits her in a sitting position on the floor and places her hand beside her so she can lean on it. She stays there, frozen, while he dances alone. When Wells leaves, Tuason replaces her in a more equally balanced pairing with Green.

In the end, the light darkens and the screens return to misty shapes. People are still leaving; others wait, accustoming themselves to absence.

Petronio chose to revive his fine 2002 City of Twist for his Joyce programs (April 6 through 11). An interesting choice, since he had begun work on it before 9/11. With its Laurie Anderson score and fashionably distorted costumes by Tara Subkoff /Imitation of Christ, it suggests a paean to the city’s toughness, its speed, its transformations, layered over a different sense of loss from that expressed in the new piece.

Petronio has never programmed a work by another choreographer, and guest stars aren’t really his thing. All the more provocative (and mysterious) is the fact that at the Joyce, he performs a four-decades-old solo by Steve Paxton, and Wendy Whelan of the New York City Ballet dances a brief solo, extracted from Petronio’s 2003 Underland and given the title of Ethersketch I (late-breaking change: Whelan will dance at every performance).

Why Whelan? Well, upon winning a Bessie last year, this superb ballerina announced slyly that—her NYCB schedule notwithstanding—she was available. Petronio took her up on it. I doff my virtual hat to her. Wearing soft slippers, a tiny skirt, a sparkling sleeveless blouse, and a be-jewelled golden collar (costume by Karen Erickson), she aces the sweeping leg gestures and yanked-off-center stances and sinuous flow that unfold alongside Muhly’s recorded score. Compared with the Petronio dancers, she’s slightly unyielding in the neck and shoulders during transitions. Never mind. Opening-night spectators let her know we loved her.

And why Paxton? I’m not sure. Except that, as Petronio explains while performing the solo, Paxton visited Hampshire College when Petronio was an undergraduate there and taught a class that stunned the latter into what turned out to be a career.

I’m getting ahead of myself. In 1970, Paxton was invited to stage his Satisfyin Lover at New York University. I’d seen it in March of 1968 at St. Peter’s Church. Thirty-two people wearing anything they felt like wearing gradually walked across the gymnasium. There was a chair or two someone could sit on a while if she/he had a mind to. It felt like a celebration of our ordinariness as well as a statement about what could be considered art.

For the 1970 version, Paxton got the idea of casting 32 red-headed people and having them walk naked. NYU cancelled the performance. Instead, in a big, open space in NYU’s former Eisner-Lubin Student Center (the Skirball Center occupies its footprint now), he performed Intravenous Lecture. I was out of town, but from what people told me, he had a doctor attach him to an intravenous drip and then walked around, talking to the audience. I got the impression that he held the bag of fluid himself (maybe not). I don’t know whether he improvised much dancing, but one of his points, I believe, came in the form of question. Which was more disturbing to look at—a bunch of naked people walking across a space or a man with a needle in his arm? What was the goal of censorship anyway?

It is this improvised solo that Petronio, with Paxton’s blessing elected to perform. His version doesn’t, of course, have the immediacy of the original, although censorship keeps coming up in far-right-wing rants, and we currently battle the issue of state-mandated vaginal probes. On opening night, Dr. Glen Marin hooks Petronio up to the drip (at each performance, a different doctor does the job and takes a bow). The bag of saline solution is then hooked onto a stand, and while Petronio wanders, gestures, slides into little flashes of dancing, and lies down for a moment, dancer Sciscione follows him with the wheeled stand, making sure he doesn’t stretch the line too far. The sight is strange and disturbing—the clear-plastic tubing comes to look like a fragile lifeline, an umbilical chord, a leash, the baggage we tote wherever we go.

Petronio speaks of the body as something to love, honor, and obey in all its disastrous and transformative and beautiful moments, but he focuses most specifically on an experience in his past. In brief, he was arrested in London, where he was living in the late 1980s, for going to a neighborhood store wearing (accidentally) a Vivienne Westwood T-shirt that displayed two men in a sexual act that the arresting officer could only, with difficulty, bring himself to name. Homosexuality was a criminal offense in England at the time. Petronio’s offense was “inciting public unrest.”

That’s sort of what he arouses in the theater by performing Intravenous Lecture. Not a bad idea. And an interesting counter to the thrill of watching the valiant, transfigured bodies of his dancers.

Deborah —

This is illuminating, as always. But I would point out that there is some misunderstanding at the end of your otherwise fine discussion of Intravenous Lecture — and at the moment I’m not sure just what Stephen said on Wednesday, when Jack and I were there — but the Sexual Practices Act of 1967 decriminalized acts between males over 21 in England and Wales. Indeed, the first time that Jack and I could legally make love was when we were living in London in 1970-71 after five years together. So the charge against Stephen was the image on the T-shirt he had rapidly donned to go in search of coffee, which is why his case was dismissed.

George

Very nice to read this good review, thank you, I just wanted to point out, that the designer Gudrun & Gudrun and the visual artist Rannva Kunoy are not from Iceland, but from Faroe Islands.

This just goes to show that I should consult maps and British anti-gay laws. Somehow, I thought the Faroe Islands were close enough to Iceland to be considered part of it. But, no, they’re adrift in the middle of the ocean. And I obviously misinterpreted something Stephen P. said.

Beautiful, thoughtful and inspiring writing. Thank you.

Deborah,

What a really lovely review “Contending with Loss” is. Thank you.

George

As we so frequently are, George Jackson and I are in complete agreement. And as a former redhead (I now match my dusty orange cat all too well) I think Petronio’s idea of a performance by redheads only is wonderful, wish NYU, that bastion of academic freedom for god’s sake, hadn’t cancelled it because of lack of costumes. I hope our contemporary dance presenters, White Bird, bring Petronio back to Portland soon; this work sounds so very beautiful and compassionate, for lack of a better word.

How lucky I am to have your x-ray eyes on my work again Deborah.

Your turn of phrase in writing about Architecture coveys so much of the state in which we were creating.Tremendous thanks for your insightful writing.

As for the legality discussed in my IVL it was men “kissing in public” that was prohibited by law in Great Britain

at that point in time.

Watching dancing on this side of the country, but watching the current political shenanigans available everywhere, Intravenous Lecture sounds as fraught now as I’ve always thought it must have been originally — I’m glad to think of it again, but frustrated to realize how appropriate it still is.