When David Gordon first presented his Dancing Henry Five in 2004, his reasons for choosing that particular Shakespeare play on which to wreak inspired havoc were obvious. In both England’s invasion of France in 1415 and the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq, the justification was flawed, and the evidence supporting it flimsy. Also, just as Prince Hal, a rowdy pub crawler, reformed with a vengeance as soon as the crown encircled his brow, George Bush the Younger, cast aside his carousing years at Yale and became a born-again Christian.

It takes a witty craftsman of dance theater like Gordon to turn a heroically jingoistic play into a wry but fervent plea for peace. And seven years later, as revived for Monclair State University’s sterling Peak Performance series, Dancing Henry Five (labeled by its creator as a “pre-emptive postmodern strike & spin”) sends a message that still rouses slumbering indignation and anger. Take note: the Battle of Agincourt not only prolonged the Hundred Years War, but led indirectly to England’s dynastic Wars of the Roses.

Shakespeare’s Chorus warned patrons of the Globe Theater in 1588 that the spectacle would be minimal: “Can this cockpit hold the vasty fields of France? Or may we cram within this wooden O the very casques that did affright the air at Agincourt?” Nope. Gordon’s own superb Chorus, Valda Setterfield, disarmingly confidential in manner, tells us that postmodern choreographers are used to make-do scenery and costumes, and, after all, for Dancing Henry Five, the Pick Up Performances Co(s) is trying to suggest two large armies at battle with “seven dancers, three dummies, and me.”

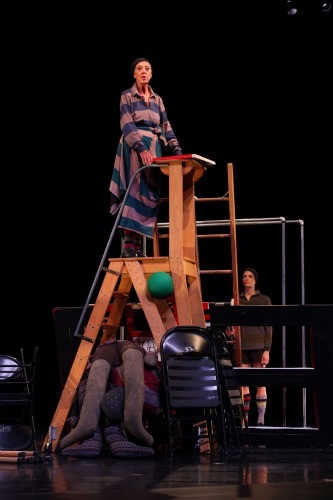

Gordon, however, provides an armature on which to hang the instructions that Shakespeare’s Chorus doles out. “Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them printing their proud hoofs i’ the receiving earth.” Okay, have the dancers stand on chairs and prance carefully in place (the English forces move gradually onto the field at Agincourt). Have them grab poles, rush into formations, and bang the poles urgently on the floor (the horses are galloping now). A ladder on wheels becomes a horse for Henry. The music gets our pulses racing (it’s the corresponding stirring passage from William Walton’s score for Laurence Olivier’s 1944 film of the play).

The program lists the provenance of the mountain of props that’s onstage as the piece starts. Many items have been re-purposed from earlier Gordon works. The effect is simultaneously threadbare and rich. The costumes look as if a canny designer (none credited) had ransacked a variety of bureau drawers. The performers wear black shorts and caps, rugby shirts with toned-down stripes, and striped socks. Fabric panels are handed out from a rack when anyone needs a cape or a skirt. These double as carpets for royalty to tread on, billowing waves, and the ships that cross the English Channel; three cast members stand on them, bravely erect and motionless, and are pulled smoothly across this wooden sea.

Gordon has pillaged other storehouses as well. Olivier’s voice and those of actors from his film deliver crucial speeches from Shakespeare’s text—Olivier’s readings often interwoven with Christopher Plummer’s delivery of them for Henry V: A Shakespearean Scenario. Walton’s movie music draws on Canteloube’s Songs of the Auvergne (which itself drew on folk songs), and Gordon has also appropriated a passage from Walton’s ballet The Wise Virgins that Walton plundered from Bach (“Sheep May Safely Graze”).

Flexibility, speed, and flow are hallmarks of Gordon’s work, as are an everyday performing manner and non-virtuosic movement. Throughout the hour that the piece lasts, the dancers (Karen Graham, Robert La Fosse, Michael Bishop, Lauren Kelly Ferguson, Kendahl Ferguson, Omagbitse Omagbemi (especially memorable), Alessandro Pellicani, and, of course, Setterfield) literally swirl and sweep the action along. They, the props, and the set are always on the move—turning and being turned and turning into something or someone else. Political strategies, for instance, are embodied in a neatly patterned game with one, then two large rubber balls (an allusion to the tennis balls sent to Henry by the Dauphin of France to mock the former playboy’s readiness to reign). Tosses, catches, and bounces are cleverly calibrated to the music but also carry elements of risk and surprise. Like war.

Gordon slyly makes the contrast between Shakespeare’s style and his own both jolting and beguiling. When Falstaff, Hal’s discarded drinking companion and mentor in dissipation, is dying, Setterfield adds a pillow to her outfit to suggest girth and lies down on a wheelable table; the recorded voice of Freda Jackson (Olivier’s Mistress Quickly) speaks poignantly of his last moments, and King Henry looks through the window in the frame the others have assembled. Then Setterfield pushes the sheet off her face, sits up, and says briskly, “OK, Falstaff is dead,” and we move on with her.

In Dancing Henry Five, Henry’s courtship of Catherine of Valois, the French King’s daughter (a prize that was part of the negotiations) proceeds as a version of a stately basse danse—with Setterfield, skirted up, as Alice, the princess’s duenna, slipping around and between Henry, the victor (La Fosse) and his betrothed (a charmingly naïve Graham). It’s an elaborate negotiation rather than a wooing. As Setterfield’s Chorus subsequently remarks, “big weddings are hell to pull off.” And for the delightful scene in which Alice gives her mistress an English lesson in preparation for her queen-of England future, Setterfield and Graham’s gestures for “fingers,” “elbow,” and so on are synchronized with the film dialogue, yet form and dissolve within a dance language.

Jennifer Tipton’s lighting is at its most splendid in the nighttime-glow it provides on the eve of battle, when the soldiers assemble tents out of what they find and crawl in and out of them. Then when the melee of charging horses, lunging soldiers, and flying dummies is over, she turns the stage into a gray, moonlit field of fallen bodies amid the detritus of war.

Setterfield, a brilliant actress, is in a sense Shakespeare’s conscience, which crops up only briefly in the play in the words of a poor foot soldier on the eve of the battle. She is acid on the subject of combatants who announce that God is on their side, and furious when she says that if she doesn’t want her son to go to war, and war seems to be unavoidable, that must mean that she wants someone else’s son to die.

Olivier made his film during World War II—a war that has gone down in history as just. For all the grandeur of his Henry V, he, too, made do; all the chain mail was string, knitted by nuns and painted silver. Ireland stood in for France. Nor did Olivier know how that 20th-century war would end. Maybe that’s why he emphasized the sadness in the speech that Shakespeare wrote for the Duke of Burgundy; aided by shots of ruined fields and despairing survivors, it becomes a heartfelt statement about the aftermath of war for the common people of France, who knew and cared little about their rulers’ lust for conquest and possession.

As wonderful as it is to see Dancing Henry Five through Deborah’s eyes, I long to see it with my own. Gordon’s intelligence as a choreographer is phenomenal and to make a political piece without being didactic is a real achievement. Moreover, it’s still what we used to call relevant in the Sixties.

I’d like to point out that Olivier’s Henry V, which I saw with my father when I was about ten, is not the only brilliant film of Henry V: Kenneth Branagh made his own version, about fifteen years ago, maybe longer,with exceedingly raw battle scenes (Olivier’s were extremely stylized, elegant in fact) making a much stronger anti-war statement. It’s a powerful film, though it lacks the leavening charm of such scenes as the English lesson, perfect fodder for a duet.

The moment I discovered these pages was like wow. Thanks for making your effort in making this article.