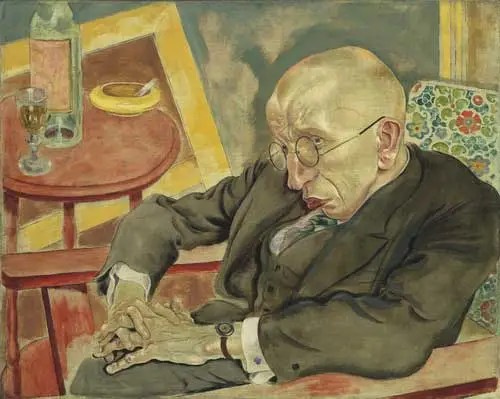

In articles on two successive days at the beginning of this month, the NY Times reported on cultural-property controversies regarding the restitution of artworks with sketchy Nazi-era ownership histories, and the repatriation of antiquities thought to have been illicitly exported from their countries of origin. In both articles, writers Patricia Cohen and Tom Mashberg, respectively, omitted crucial facts bolstering museums cases for retention of two hot-button objects—the Mummy Mask of the Lady Ka-nefer-nefer. Egyptian, Dynasty 19, (click its image) at the St. Louis Art Museum, and George Grosz‘s Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse at the Museum of Modern Art. (There are now late-breaking legal developments in the Mummy case, to be discussed below.)

Photo by Lee Rosenbaum

A responsible, thorough report on those two controversies, giving fair weight to easily ascertainable information supporting the museums’ cases for retention, would have given readers a better understanding of the complex issues in these thorny disputes.

Proponents of repatriation and restitution often see such gray-area controversies in black-and-white. The reflexive response of advocates for the return of objects long held by American museums is that requests by nations or individuals for objects that they believe to have been looted, stolen or misappropriated should, in most (if not all) cases, be honored.

It’s not that simple.

I strongly support repatriations and restitutions when convincing evidence warrants them. But it takes time and scholarship to research the histories of such objects. A museum’s decision on whether or not to relinquish them is often a tough judgment call, depending on the available facts and how they are weighed.

In the case of Ka-Nefer-Nefer (which is now appears to be heading to the U.S. Court of Appeals), reporter Tom Mashberg mentioned in his NY Times article that the U.S. government “has sued the [St. Louis Art] museum to secure the object’s return.” But he inexplicably failed to mention the fact that a U.S. District Court judge last year threw out the government’s lawsuit in a nine-page opinion (which I reported on in this CultureGrrl post).

Judge Henry Autry them wrote that the government had “misse[d] a number of factual and logical steps, namely: (1) an assertion that the Mask was actually stolen; (2) factual circumstances relating to when the Government believes the Mask was stolen and why; (3) facts relating to the location from which the Mask was stolen; (4) facts regarding who the Government believes stole the Mask; and (5) a statement or identification of the law which the Government believes applies under which the Mask would be considered stolen and/or illegally exported.”

The government has now resurrected its undead Mummy case, submitting an appellate brief on June 24 to the U.S. Court of Appeals (as reported by Rick St. Hilaire on his Cultural Heritage Lawyer blog). The government argued that Judge Autry’s court orders constituted “a clear abuse of discretion.” Matthew Hathaway, the museum’s press officer, told me that “the deadline to file our reply is July 25, and we expect to meet that deadline.”

In the case of the Grosz portrait, Patricia Cohen quoted MoMA spokesperson Margaret Doyle‘s rudimentary rebuttal to charges by the artist’s descendants that “Herrmann-Niesse” and other Groszes in MoMA’s collection were subjected to forced sales by the (non-Jewish) German artist’s Jewish dealer, Alfred Flechtheim. Doyle cited “years of extensive research…including numerous conversations with Grosz’s estate.”

Cohen could have learned about (and reported on) the details of the museum’s due diligence, set forth in the 13-page 2006 report that she alludes to in her Times article, commissioned by MoMA from former U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. That report, provided to me by Doyle upon my request, lays out the case for its author’s conclusion that Flechtheim’s gallery was not “Aryanized,” as alleged by Grosz’s heirs, and that “the failure of Grosz to make a claim [for “Herrmann-Niesse”] for more than 30 years,” even after writing to both his brother-in-law and a friend that it had been “stolen” from him, “had deprived MoMA of the “opportunity to ascertain the facts when they were still reasonable fresh and knowable….It would have had the opportunity…to resolve the matter then and there at relatively little cost to it.”

Katzenbach also stated that “whatever Grosz meant by his ‘stolen’ references, he did not note the portrait as stolen or confiscated in his postwar restitution/compensation claims with respect to unlawful acts of the Nazis….The provenance of the painting after the [1932] Brussels exhibition until it was sold by Charlotte Weidler to MoMA in 1952 is uncertain.”

Much more detailed accounts of the Grosz/MoMA controversy are set forth in William Cohan‘s 2011 ARTnews article, MoMA’s Problematic Provenances and in Nina Burleigh‘s 2012 NY Observer article, Haunting MoMA: The Forgotten Story of “Degenerate” Dealer Alfred Flechtheim.

There’s no question that this is a “gray-area” case. We may never know for certain who is “right”—the museum or the heirs. But although MoMA ultimately took the easiest route to a favorable court decision—the statute-of-limitations argument—it appears to have done so only after making an protracted effort to evaluate the painting’s murky history from (as Katzenbach characterized his assignment) “a moral or ethical viewpoint.”