Critical Difference: November 2009 Archives

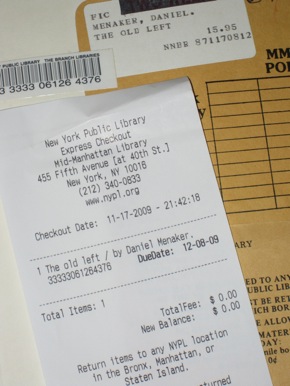

The autumn weather was perfect the other night for a stroll through Midtown. So when the theater let out on 45th Street, I headed a few blocks south, cut through the holiday maze of Bryant Park, and crossed Fifth Avenue to the Mid-Manhattan Library. It was late, but there was no need to hurry: The library was open 'til 11 p.m.

Even as I plucked the book I needed from a shelf in the fiction section, I felt a sort of warming gratitude. The New York Public Library fought hard earlier this year to fend off budget cuts that would have devastated its ability to provide services just when demand for them is highest. Its success says a lot about the city's priorities -- and about its wealth, too.

Elsewhere in the nation, the recession is having an ugly effect on libraries. Today's papers alone tell stories of numerous struggles. In Pittsburgh, several branches of the Carnegie Library face closure if funding isn't found to keep them open, and in Southern California, according to the Los Angeles Times, "the city of Colton shut down its three libraries and laid off nearly 60 employees to help plug a $5-million hole in its budget." The city of Ventura plans to close its most heavily used branch.

It's vicious out there -- for the populace and for our libraries, whose worth we recognize most clearly in bad economic times. So those of us who live in a place where the public library is not only open seven days a week, but open late as well, have reason to marvel.

It isn't a luxury, but it feels that way. Who could fail to cherish that?

Sage counsel from Amy Poehler: "Girls, if boys say something that's not funny, you don't have to laugh," she said this week at Glamour's Women of the Year Awards.

Is it too great a leap to suggest that Poehler's girl-power advice gets at one of the root causes of women's underrepresentation in so many areas of the arts?

Maybe women, from early childhood on, are trained to be too amenable an audience, ever willing to watch and listen -- politely, appreciatively, passively -- to male performers and writers and directors. Meanwhile, our culture is so certain little boys wouldn't be attracted to narratives about girls (or is it that we fear they would be?) that we don't even test the hypothesis. Children's storybook characters, their movie heroes, even nearly all of the Muppets on "Sesame Street" are male. And so yet another generation grows up with the belief that male equals mass appeal, while female equals niche.

When you're perceived as comprising a niche even though you're the majority, good luck breaking into the mainstream -- which, as it happens, is dictated (loudly, raucously) by the preferences of the minority. Sort of like how Republicans control the Senate even though the numbers say they don't.

What brings this on is Bill Carter's New York Times story today about the absence of women on late-night TV writers' staffs. The most startling fact in the piece -- which adds some depth and color to other recent coverage of that abysmal employment scenario -- is that there are more female viewers of those shows, and of TV in general, than there are male viewers. David Letterman's "audience is almost 55 percent women; [Jay] Leno's is more than 53 percent, and [Conan] O'Brien's just over one half. Yet the writing room and sensibilities of the show itself remain largely male."

It's a maddening piece of information, not least because it lines up so well with other female-majority stats: Women attend the theater more often than men do; read vastly more fiction than men do; want to go to, and work in, the movies just as much as men do. And yet female playwrights and plays about women remain scarce; rosters of "important" novelists, let alone nonfiction authors, tend to be overwhelmingly male (or, like Publishers Weekly's list of 2009's top 10 books, all male); and Hollywood, which must have the attention span and cultural memory of a gnat, is genuinely surprised whenever a female-centric movie is a monster hit. (Wasn't "Thelma & Louise" -- which, by the way, I saw with three guys when it came out in 1991 -- supposed to change that once and for all? Sigh.) And let's not even get into dance, where female choreographers are still struggling to commandeer even a little bit of the spotlight.

Pondering the egregious underrepresentation of women in the theater industry, playwright Marsha Norman frames the problem this way in the current issue of American Theatre:

The U.S. Department of Labor considers any profession with less than 25 percent female employment, like being a machinist or firefighter, to be "untraditional" for women. Using the 2008 numbers, that makes playwriting, directing, set design, lighting design, sound design, choreography, composing and lyric writing all untraditional occupations for women. That's a disaster if you're a woman writer, or even if you just think of yourself as a fair person.

As she also notes, "it's awful all over the arts world for women." So there's that.

In trying to combat this arts-world disaster, perhaps women can take a lesson in what not to do from the Democrats, who have a longstanding, extremely self-defeating habit of being polite and empathetic beyond the point of reason. They also have a catastrophic tendency to be cowed by Republican name-calling and the prospect thereof, which means they exercise their backbone less than they otherwise might, even when they're in the majority.

Women, socialized to be polite and empathetic, simply are not, as a group, as assertive as men are -- partly, perhaps, because in behaving that way they risk being stuck with labels like "aggressive" and "bitch" (or, God forbid, "feminist"). But the numbers here are in our favor: numbers that say women make up more of various lucrative audiences than men do, numbers that say women aren't being properly served, numbers that say -- as Norman points out -- basic fairness is being ignored, and it's getting in the way of people's livelihoods.

There is some hope even in the appearance of Carter's Times piece today, which suggests this issue has legs. There's a glimmer of hope, too, in an unlikely spot, comedycentral.com, which streams full episodes of both "The Daily Show" and "The Colbert Report," generally targeting a Wired-meets-"Animal House" demo with ads for beer, BlackBerrys and incipient boy-blockbusters like "Paul Blart: Mall Cop."

But one day not long ago a cosmetics ad came on. I nearly fell off my chair: Someone had noticed -- at last, at last, at last -- that women were watching.

Well, yes. We've been there all along. Might as well try to sell us something.

Okay, then. Now that those shows have picked up on our presence, maybe they and the other late-night guys will acknowledge, too, the absence of women in their writers' rooms, and finally do something about it.

November 12, 2009 4:57 PM

| Permalink

Not even a half hour into the 80-minute performance, much of the row behind us gave up and left, clumping and clattering out of the theater. A short while after that, more of the crowd fled, the wood of the risers amplifying their every footfall. Those of us who remained were quiet, whether out of absorption, puzzlement or indifference. I couldn't detect the tenor of the audience, or even the reaction of the good friend beside me. Occasional sparse laughter aside, the spectators at yesterday's matinee of Richard Foreman's "Idiot Savant," at the Public Theater, were so subdued as to seem unresponsive.

But would we have been so at the curtain call? It's impossible to know, because there wasn't one. Instead, the disembodied voice that had spoken to us and to the actors at the beginning of the play ("Message to the performers: Do not try to carry this play forward") spoke again at the end to tell the audience that the performance was over and we were to exit now. The applause that came anyway from those who were not immediately out the door was befuddled, and consequently muted: Are we really supposed to leave without saying thank you?

It's the actors who bow at a curtain call, but it's not only their performance that we're applauding. It's also the writing, the direction, the design -- or, in the case of Foreman, more likely those same three things in reverse order, language being the least of it with him. Nearly everything psychological about his voyages into the imagination is perceptible in his weird, sometimes hallucinatory stage pictures, so vivid that knowledge of English is probably not a prerequisite for viewing. The delicious set of "Idiot Savant" is like a shoebox diorama made human-scale (and, for what it's worth, the best spatial use of the Public's difficult Martinson stage I've ever seen); the actors, the costumes, the scores of props are objects Foreman moves around his diorama. What he's creating is spectacle, and we are spectators. Which is a step removed from being a true theater audience: We're observers, not crucial participants.

And yet when my friend and I walked out onto Lafayette Street (he said he loved it, by the way; so did I), I couldn't help feeling a little bit bad for the actors. If I hadn't been able to gauge the audience's response, had they? Some of the best curtain calls come after performances like that, when a seemingly tepid crowd turns out to have been with the actors all along. If our audience was -- and maybe they weren't; maybe it was mostly a crowd of "Spider-Man" fans who'd come to see Willem Dafoe, mixed with white-haired matinee-goers who are Foreman's contemporaries but not his peers -- the cast will never know it.

Americans are notoriously stingy with their applause, so it may be a little weird that I'm bothered, as an audience member, by the lack of a curtain call. Nonetheless, I am. The absence of it fits the form of the piece, but it doesn't quite fit its spirit, which is nothing if not generous. There's no quibbling with the rest of "Idiot Savant": From Foreman's overflowing imagination come a giant papal stigmata duck and a spotted spider, too; it's simply ungrateful to complain. But amid all that bounty, he leaves us hungry for the chance to give thanks.

... in 140 characters, max. Garry Trudeau is a genius.

November 6, 2009 11:01 AM

| Permalink

At Politico, Pia Catton has a fun look at the social links between the members of the President's Committee on the Arts and the Humanities. As she writes, "these 26 private-sector appointees are intricately connected through years of leadership in the overlap of politics, arts and culture. Studying their resumes, some clear patterns and paths emerge." An accompanying chart by Sarah Lauren Bell maps the circles of influence.

Articles and charts being limited by nature -- they can't, after all, go on forever -- there's amusement for the reader, too, in finding connections the piece doesn't mention. Quick! How many additional social groups does George C. Wolfe belong to?

November 6, 2009 9:38 AM

| Permalink

A few elegant chairs. That's all it took to significantly ameliorate a design disaster in the Barclays Capital Grove at Lincoln Center.

The god-awful concrete benches marring the plaza just north of the Metropolitan Opera House are still there in all their multifaceted dreadfulness, but it's only fair to point out -- a bit belatedly -- that visitors seeking a place to sit under the trees now have a far better option.

In the new context, the benches serve as a frame for the activity inside them. An ugly, ill-advised frame, but one that can more easily be ignored.

November 5, 2009 5:00 AM

| Permalink

There was a startling melancholy to a street scene in Chelsea yesterday, just off Eighth Avenue. An old Boston Globe delivery truck, now with New York plates, idled at the curb, removed from its native habitat, disconnected from its original purpose. The painted lettering that betrays its past life is only partly scraped off, legible enough to lend the new owners -- a Brooklyn firewood delivery business -- a certain retro cool.

But melancholy is the mood where newspapers are concerned. A reporter friend, as weary as I am -- as we all are -- of the endless coverage of newspapers' demise, roused himself from his professional ennui the other day to recommend a stellar essay on the subject. I was skeptical; who wouldn't be? But Richard Rodriguez's "Final Edition," in the current issue of Harper's Magazine, is lovely, literary, smart: the kind of thing that reminds you why you fork over money to read good writing -- which you'll have to do for this, even online.

A taste:

We are a nation dismantling the structures of intellectual property and all critical apparatus. We are without professional book reviewers and art critics and essays about what it might mean that our local newspaper has died. We are a nation of Amazon reader responses (Moby Dick is "not a really good piece of fiction"--Feb. 14, 2009, by Donald J. Bingle, Saint Charles, Ill.--two stars out of five). We are without obituaries, but the famous will achieve immortality by a Wikipedia entry.

Like all the best obits, Rodriguez's essay tells us what's been lost, and why it matters, not least to our sense of place. But, as he points out, "An obituary does not propose a solution."