Review: 'The Play That Changed My Life'

Talking lima beans turned Lynn Nottage into a playwright -- or they helped, anyway. Without "Succotash on Ice," the children's play she saw as a small girl the very first time she remembers going to the theater, there might not have been a "Ruined."

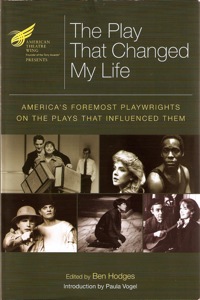

Talking lima beans turned Lynn Nottage into a playwright -- or they helped, anyway. Without "Succotash on Ice," the children's play she saw as a small girl the very first time she remembers going to the theater, there might not have been a "Ruined.""I remember turning to my mother, with my mouth wide open, speechless -- I didn't even have language to ask her what was going [on] or express my wonder," she tells interviewer Ben Hodges in "The Play That Changed My Life: America's Foremost Playwrights on the Plays That Influenced Them" (Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 173 pp., $18.99). "I was just like, 'Do you see what I'm seeing? Talking lima beans?'"

More cerebral plays, such as "Mother Courage and Her Children" and "A Raisin in the Sun," would significantly affect Nottage later on, but that kids' show on the stage of a Brooklyn community college "really transformed me," she says, "because it opened up a whole new creative universe for me. It is where I really feel that I understood how magical and special theatre could be."

Nottage's lima bean rhapsody is one of many illuminating moments in the American Theatre Wing's frequently funny, surprisingly charming, occasionally heartbreaking new collection of essays and interviews. Edited by Hodges, with a foreword by Paula Vogel, the book assembles 19 of the theater's usual suspects, many of them Pulitzer Prize winners, to explain what lured them into their line of work. A distinguished 20th, Edward Albee, opens the proceedings with a sparkling curtain raiser.

Not all of the playwrights directly answer the title's implicit question, but many of them, Albee included, trace their love of theater back to childhood or adolescence. There is 8-year-old Christopher Durang, already writing plays in New Jersey; there's kindergartner Beth Henley, catastrophically disappointed by the miscast princess in "Jack and the Beanstalk"; there's Sarah Ruhl, at 7 or 8, weeping on the living room floor because she's being left at home on closing night of her mom's production of "Enter Laughing."

All three of them credit their early interest in theater to their mothers: Durang's loved to go to the theater, and to read plays as well; Henley's mom was an actress in Jackson, Miss., and Ruhl's was an actress and director in suburban Chicago -- as well as a very good sport, apparently, about the notes her little girl gave on her rehearsals.

David Ives, growing up in blue-collar South Chicago, was seldom taken to the theater, but his dad supplied necessary knowledge by other means. "My father spent my childhood sitting in his armchair puffing on Pall Malls and reciting to me the bit players and supporting actors of old movies as they ghosted across our tiny black-and-white television screen," Ives writes. In Brooklyn, Donald Margulies' father was teaching him the same thing -- and quizzing him on it.

Nothing in "The Play That Changed My Life" is ancient history, of course, which makes it all the more striking as a reminder of the mutability of theater's presence in the culture. Ives recalls being riveted as he listened to plays on the radio as a boy; so does A.R. Gurney, who suspects those broadcasts are responsible for his learning "subliminally how to tell a story primarily through dialogue." Horton Foote, whose posthumous contribution combines excerpts from his "Genesis of an American Playwright," provides serendipitously timely perspective on the Pasadena Playhouse and mentions, instructively, that New York theater during the Great Depression seldom attempted more than superficial social commentary.

What, then, of the life-changing plays? David Auburn saw his on PBS. He writes of the shock he experienced at 17 upon discovering, in John Guare's "The House of Blue Leaves," a play utterly unlike "the thoughtful, well-tailored contemporary classics" he was accustomed to seeing at the Arkansas Rep. "I still have the tape I made of the broadcast," he notes. (So much for the argument that theater loses its power on TV.)

For Diana Son, it was "Hamlet." Deeply enamored of the play during her senior year of high school in Delaware, she was confused and wary when she heard that a woman would play the title role in the production her AP English class was traveling to New York to see. Then Diane Venora walked onstage at the Public Theater, and Son felt herself "being worked on alchemically."

The essays, almost all of them written for this collection, almost all of them lovely, fare better than the handful of interviews conducted by Hodges. In theory, the Q&A's are an excellent compromise for playwrights who didn't want to contribute essays; in reality, Hodges seems more intent on shaping the narratives than on listening to what his subjects are saying. John Patrick Shanley, trying to draw a parallel between theater and church -- not an original thought, but one that surprised him as a Catholic high schooler in the Bronx, watching "Cyrano de Bergerac" from the wings -- has to drag Hodges back to the topic.

It appears as well that there was no copy editor for the book, which is riddled with stop-you-in-your-tracks typos. Margulies' beautiful 1992 essay, "A Playwright's Search for the Spiritual Father," which has been published in The New York Times and in Margulies' own collection, "Sight Unseen and Other Plays," manages to show up here with brand-new typos. When the playwrights entrusted their work to this project, they deserved to be taken care of better than that.

One of them, in fact, would have been better served -- as would the book -- if her essay had been rejected. Regina Taylor's "Crowns" may be hugely popular, but her piece extolling Adrienne Kennedy's "Funnyhouse of a Negro" is abysmal: proof that writing prose and writing drama demand very different skills.

Because the playwrights are deployed in alphabetical order, from David Auburn to Doug Wright, Taylor's dreadful contribution is where an 11 o'clock number might have been. But Wright's essay on Charles Ludlam and the Ridiculous Theatrical Company -- the book's gorgeous, full-hearted finale -- is note-perfect from its opening line: "For most of my childhood, I was in love with my best friend, Bruce." That was back in Texas. Years later, as young gay men in 1980s New York, they would discover Ludlam together, becoming deliriously devoted "scholars of the Ridiculous" only shortly before the playwright-actor died of AIDS.

Given the carnage AIDS has wrought in the theater, it feels not only fitting but essential that the collection ends with Wright's sweet elegy to Ludlam, his young self, and his own best friend. The essay nicely underscores the point of the book, too, with an anecdote connecting Ludlam's work to Wright's Marquis de Sade play, "Quills."

"Quills was widely reviewed by the New York press when it opened at the New York Theater Workshop in 1995," Wright recalls, "but to my astonishment, not one critic cited its obvious debt to Ludlam." Fast-forward several years to the set of the film adaptation, starring Geoffrey Rush. Steeping himself in Sade's writing and dousing himself in patchouli oil, the actor was still trying "to nail the precise tone for the role."

At last, in Wright's playscript, Rush stumbled across the key.

"'It's Ludlam, isn't it?' he whispered to me fervently. 'I reread the play last night. It's pure Theatre of the Ridiculous!'"

With that discovery, Rush understood the ancestry of Wright's work.

Such is the purpose, and the pleasure, of "The Play That Changed My Life": mapping the genealogy of contemporary American drama, delineating which fresh green shoots sprouted from which branches of the family tree. And watching what happens when you plant talking lima beans in a little girl's mind.

February 18, 2010 2:57 PM

| Permalink