June 2009 Archives

If only Alice Hoffman had given a thought to David Shipley and Will Schwalbe's "Send" before she raged on Twitter Sunday about Roberta Silman's Boston Globe review of her new novel, "The Story Sisters."

I sympathize with Hoffman; truly I do. I haven't read her book, but I've read the review, and Silman's writing is pedestrian -- inelegant. Any spoilers the review contains, as Hoffman says it does, are inexcusable. (And, though I don't believe this figured in the tweets, did the editor have to run quite such an unflattering photo of her?)

But sending messages out to the world is not generally a good idea for someone in the grip of fury. That's where the advice from "Send," a book of e-mail etiquette, comes in.

"Nothing bad can happen if you haven't hit the Send key," Shipley and Schwalbe write.

Or the Update button. Whichever.

June 30, 2009 12:08 AM

| Permalink

From her review of HBO's "Hung," yet another perfect line:

"I'm a little concerned that I'm making this sound clever; it's not."

June 29, 2009 7:54 PM

| Permalink

A friend just mentioned a conversation with a woman who, until recently, was an artistic director at a prominent regional theater. Prompted by Emily Glassberg Sands' college thesis on female playwrights -- and consequent reports that female artistic directors and literary managers are to blame for failing to produce women's scripts -- she said she was feeling guilty.

Does she, personally, have any reason to feel guilty? I don't know. I do know that there's a good chance a lot of women in theater are feeling similarly guilty, even though Sands' research does not prove they're at fault, nor does it suggest that there is a single cause for the low number of plays by women on American stages.

Guilt can be a terrific motivator. If guilt, deserved or undeserved, prompts women in theater to take a closer look at scripts by women; to make more active efforts to seek out, commission, nurture, and produce female playwrights; and to question their own assumptions about what their audiences are hungry to see, or even willing to see, then it could be a very good thing.

But if women are the only ones feeling guilty, there's something terribly wrong with the response. That is one of the huge dangers of pointing the finger at women: In that interpretation of Sands' paper, men are off the hook. If they're not part of the problem, they don't need to trouble themselves to be part of the solution, except maybe in making sure that a guy gets the next a.d. or literary manager job that opens up. Women, after all, can't be trusted to be fair to other women, right? Wrong, but you wouldn't get that impression from the eagerness to label them as biased.

Male artistic directors and literary managers, as a group, are no less to blame than are female artistic directors and literary managers, as a group. Male artistic directors also occupy far more of the high-profile, big-budget jobs -- which means the 50-50 gender split among respondents to Sands' survey skews the results in a way that doesn't correspond to the real world. Men aren't off the hook. No one is.

If anyone is going to feel guilty about the underrepresentation of women's plays on our nation's stages, let that guilt be a motivator for positive change. And let that guilt be shared.

When I worked at the conservative New York Sun, I tended to keep mum about politics. A lot of the liberal staffers did the same. But after the paper folded last fall, just as the presidential election went into overdrive, I began to feel slightly dishonest in not revealing my political stance to one of the paper's hard-line Republican contributors, an ardent Palin supporter with whom I'd developed a friendly rapport.

Finally, I took a deep breath and told him -- upon which he informed me that I'd given him plenty of clues. "How about your love of theater?" he asked, kindly not mentioning the time I'd spoken enthusiastically to him of Dario Fo, any right-winger's artistic bête noire.

That's the prevailing assumption about the theater: that it's liberal to the core. And maybe, in theory, it is. Practice, as Emily Glassberg Sands' thesis on female playwrights reminds us, is a different matter.

There is a crazy-making dissonance to encountering a hostile environment in what we're assured is a sympathetic milieu, at least politically. In Hollywood, another famously liberal industry, women face a similar set of obstacles, as an anonymous "emerging producer" wrote last week in The Wrap:

I never thought of myself as a feminist until I came to work in Hollywood. I'm part of a generation and class of women who were reared on the rhetoric that we could grow up to do anything. At no point did gender figure in as a limitation, and the idea that it would for anyone who might judge my capabilities seemed completely ludicrous.

It was confusing when I heard or read about women's complaints of gender discrimination -- didn't we figure all this stuff out in the '70s?

Well, no, she's discovered -- and she thinks it's time that women take some action: "We've become so complacent that a touch of extremism is warranted. You could never lose weight if you refused entertain the idea that cheeseburgers are fattening. Instead of waiting for someone to blaze a new trail, it's time that we make a more conscious change in our appetite."

No diet works, however, without a change in behavior to accompany the change in appetite. In order for female playwrights to increase their prominence in the theater, one thing they're going to have to do is make more noise: write more plays, get them out there, and better their odds simply by having a greater presence.

Sands' research relies on doollee.com for numbers on scripts by male and female playwrights; as she admits, this is a less than ideal source, given that much of the information is self-reported. But what if male playwrights -- already more numerous than their female counterparts -- are more likely to do that self-reporting? Women need to be assertive about making sure that their work is noted, too, in high-profile places.

Ours isn't a culture that encourages loudness in women; for a literal example, see the current controversy over female tennis players who have the audacity to grunt on the court. Meekness is, in fact, encouraged in us at every turn. But if a woman's object is to make her voice heard, as it is with playwrights, then being quiet is not a strategy that will ever lead to the desired reward.

In my experience as an editor, I've observed the same thing in writers that artistic directors and literary managers say they see: far more submissions by men than by women. In order to find female writers, I had to be active, not passive. I couldn't rely on women to call themselves to my attention; I could, however, rely on men to be rather fearless, and less perfectionistic than women, about putting their work out there.

Sands' research suggests that producers hold women's plays to a higher standard than they do men's, but I suspect women also hold their writing to a higher standard before they're confident enough to let a script leave their hands. That's understandable, but it's probably not helpful. Women need to be stronger, more confident champions of their own work -- and artistic directors and literary managers need to actively seek them out.

If producers would, in the process, stop assuming that audiences won't show up to see plays by and about women, that would be another step in the right direction.

Quick! Name the five most influential female artistic directors in the American theater. You have 60 seconds.

* * *

Now, in one minute, do the same with men.

* * *

How'd you do? I'm guessing much better on the second question than the first. Did you even get five names on that list?

Okay, now name the five most influential theater critics, of either sex, in the United States. Sixty seconds.

* * *

Were there any women at all among your top five critics?

The point of this little exercise is simple: Women would have to wield a whole lot more power in the nation's theater in order to be credibly scapegoated for the low number of plays by women produced on its stages.

Emily Glassberg Sands' research on the subject is a bombshell in a sleepy summer news cycle, and it raises some genuine concerns that the theater would do well to address. What the recent Princeton grad's senior thesis doesn't do -- however inconvenient the fact may be for journalists, who tend to prefer juicy reductivism, the more divisive the better -- is identify a single cause for a persistent scarcity that has myriad causes.

So you can go ahead and disregard the third sentence of Patricia Cohen's New York Times article, which says Sands' research shows that "women who are artistic directors and literary managers are the ones to blame." And, while you're at it, the lede of Philip Boroff's Bloomberg story: "Female playwrights, long aware that they're produced less frequently than their male counterparts, may now have someone to blame: female artistic directors."

But, as suggested by "Women Beware Women," the headline on ArtsJournal's link to the Times story, the popular takeaway on Sands' research is likely to be a simple, misogynistic, maddeningly familiar formula: Women are too jealous to play, or work, nicely together. Far be it from them to give other females a fair shot.

Continue reading Women, Don't Beware Women.

There are enough scary job-loss numbers floating around out there without alarming people unnecessarily, but that's what some unclear writing about Long Wharf Theatre's staff cuts has managed to do.

I've seen the misinterpretation in a couple of places, so I feel compelled to mention: Long Wharf isn't cutting 40 to 50 jobs; it's cutting about 10 percent of a full-time staff that numbers between 40 and 50 people. That's four or five jobs. Still not great news, but much better than 10 times that.

Why such a fuzzy number was given in the first place is a mystery. Surely an exact figure would not have been difficult for a reporter to nail down.

June 23, 2009 11:27 AM

| Permalink

Is everyone reading Dickens these days? I know I am, prompted by Margaret Atwood's fascinating "Payback," in which she considers debt as narrative and ponders various notions of sin attached to borrowing and lending. Dickens, naturally, is key to the arguments she makes in her slender, thought-provoking book -- a collection of lectures she gave, which on the page feel like a graduate seminar in literature with a seriously delicious reading list.

Thus my current immersion in "David Copperfield," and thus also a conversation with a friend who highly recommended the BBC miniseries "Little Dorrit." (I'm on disc 3, and he was right.)

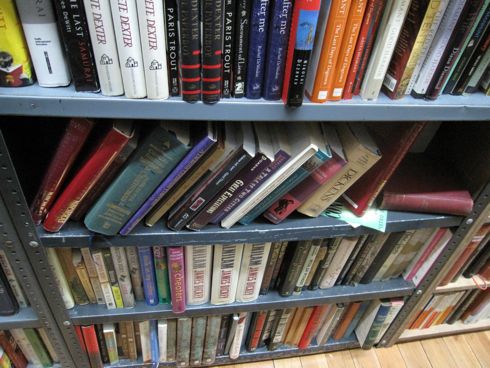

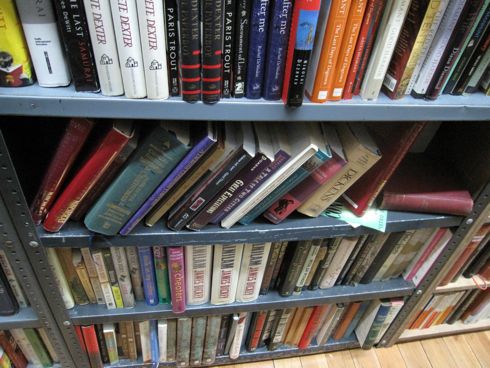

But what makes me wonder if we're experiencing some sort of rush on Dickens, perfect as he is for these hard times, is what I saw yesterday at the Strand, where the Dickens shelf in the fiction section looked like this:

It's been ravaged!

Just when you think your own government is completely ridiculous, along comes someone else's government to convince you that it's not so bad after all.

The U.K. has officially dumped the "'i' before 'e'" rule as a teaching tool. As in, they actually spent time thinking about it, then determined it to be some sort of menace to schoolchildren.

The Times of London reports it this way:

Generations of children have learnt how to spell by chanting "i before e except after c", but new guidance from the Government says that schools should stop teaching the rule because it is irrelevant and confusing.

The National Strategies document Support for Spelling, which is being sent to primary schools, says: "The i before e rule is not worth teaching. It applies only to words in which the ie or ei stands for a clear ee sound. Unless this is known, words such as sufficient and veil look like exceptions.

The thing is, the way I learned the rule, it didn't stop at "after 'c.'" The rule was "'i' before 'e,' except after 'c,' and when sounded like 'a,' as in 'neighbor' and 'weigh.'"

If that's not enough to teach a kid to look out for exceptions to the rule -- which, yes, extend beyond "a"-sounding words -- there are always parents and teachers to tip the moppets off to the fact that the language isn't quite that simple. English is littered with exceptions to its rules, and the sooner children learn that, the better. But the rules stand nonetheless, and memory devices like the "i" before "e" rhyme are helpful.

Even if some of them don't necessarily translate across the pond to American English speakers, as this bit of the Times story proves:

Masha Bell, who has campaigned for English spelling to be simplified, said: "I before e is not a good rule. There are other sayings that are more useful, like 'one collar, two socks' for 'necessary'.

Then again, in Bell's opinion, "spelling is rubbish."

June 20, 2009 5:44 PM

| Permalink

Toward the end of his review of Woody Allen's latest, "Whatever Works" -- in which Larry David plays the Allen alter ego, Boris; 21-year-old Evan Rachel Wood plays Boris's wife, Melody; and Patricia Clarkson plays Melody's mother, Marietta -- Anthony Lane ponders what the movie might have been if Allen had bothered to let go of some of the tropes to which he's held so fast for so long. "It would be a movie in which Allen interrogates his own nostalgia," he suggests.

"Or how about a retread," Lane continues, "in which Boris picks on someone his own age and finds love with Marietta?"

Wait a second.

Someone his own age? Patricia Clarkson and Larry David are the same age?

Hardly. Larry David will be 62 in a couple of weeks. Patricia Clarkson is 49. When he was 30, she was 17. In contrast, when he was 30, Hillary Clinton was, too. So were Camilla Parker Bowles, Jane Curtin, Emmylou Harris, Farrah Fawcett, Laurie Anderson, Teri Garr, Mary Kay Place, Meredith Baxter, Cheryl Tiegs, Glenn Close, Anne Archer, Jill Eikenberry and Betty Buckley.

Also in the ballpark: Sigourney Weaver, 59; Meryl Streep and JoBeth Williams, 60; Helen Mirren, Diane Keaton, Goldie Hawn and Bette Midler, 63; Mia Farrow and Swoosie Kurtz, 64; and Lynn Redgrave, 66.

And male contemporaries? Arnold Schwarzenegger, Kevin Kline, David Letterman, Elton John, Richard Dreyfuss, Meat Loaf and Bob Weir were all born in 1947.

That's what someone Larry David's age looks like, even in Hollywood.

June 18, 2009 7:11 PM

| Permalink

I love The Guardian. Truly I do. It has some of the best arts coverage on the planet. But this morning, the paper nearly made me hyperventilate.

It wasn't arts correspondent Mark Brown's story on the dismal representation of women in British theater, film and television, which I was glad to see (not the fact of the underrepresentation, but the stats, and the discussion). It wasn't the article's cheesy headline, "Leading ladies kept out of the limelight." It was where the story ran in the paper.

It's in the Life & Style section. You know: the part of the paper that has categories like Fashion, Homes, Gardens, Craft -- and Women.

Sigh.

Sigh sigh sigh.

The story is linked on the Stage page, in the Culture section, which is where I found it, but that's not where the paper's editors ran it.

Which, really, is pretty disgusting.

June 17, 2009 11:13 AM

| Permalink

The Guardian reports:

The script of the play is here, courtesy of the Royal Court Theatre, which premiered it in February.

Seven Jewish Children, the controversial play written in response to Israel's assault on the Gaza Strip, was performed for the first time in the Jewish state last night, with a couple of hundred people gathering to watch the Hebrew-language production in Tel Aviv's Rabin Square.

As is often the case with politically charged issues, some of the locals had a more nuanced view of Caryl Churchill's play than have various strident critics abroad:

"Political plays can be really superficial, but this one was serious and very significant," said Danielle Shworts, 27, from Tel Aviv. Another audience member from the city, George Borestein, 58, agreed. "I am really shocked," he said. "It was a fascinating performance and, to my great sorrow, there is a lot of truth to this play."

June 12, 2009 11:43 AM

| Permalink

On tour in China with the National Symphony Orchestra, The Washington Post's Anne Midgette examines the similarities between going to the concert hall in the U.S. and in Macau, where she finds "the same ushers pouncing like hawks on young people trying to text on their mobile phones during the show. (Both ushers and young people here showed a striking degree of determination.)"

Discouraging about the young folk, of course, but American ushers -- and their bosses -- could take a tip from their Chinese counterparts. Here, vigilance isn't necessarily the rule.

June 10, 2009 11:39 AM

| Permalink

Much as I agree with Judith H. Dobrzynski that consuming art requires a more focused attention than many other activities, I can't say that I believe etiquette is worsening at New York theaters -- not even on Broadway, as Ellen Gamerman's Wall Street Journal piece would have one believe. In my experience as a several-times-a-week theatergoer, cell phones ring far less often than they did even a year or two ago. With a legal ban in place, regulars are accustomed to turning them off, and theaters are not shy about reminding the audience (via any means necessary: Playbill inserts, recorded announcements, a word from an usher, a curtain speech) to do so.

The other examples of outrageous audience behavior Gamerman cites are simply gross aberrations from the norm, not evidence that theatergoers have lost their bearings, or that tourists and bargain hunters are lowering the bar for us all.

American Repertory Theater artistic director Diane Paulus, on the other hand, absolutely is lowering that bar with a plan to let people keep their phones on at ART this summer. It is, as she tells Gamerman, a radical idea -- but, embracing as it does the self-centeredness that's corroding so much of contemporary life, it may not have the effect she desires. Can human beings be so different in Cambridge, Mass., than in New York City? Even if what she intends to do there were legal here, it simply would not fly -- with actors or audiences.

On Saturday, I went to Ethan Coen's trio of one-acts, "Offices," at Atlantic Theater Company in Chelsea. To my right was a guy in his 20s or 30s. At some point deep in the performance, the phone in his left pants pocket went off: a few notes of quiet, almost gentle electronic melody. Shooting upward in his seat as if he'd been electrocuted, he whispered, "Oh my God," swiftly grabbed the phone, and silenced it faster than I'd ever heard anyone silence a phone. His mortification was palpable, the distraction brief.

That was the first time in a long time that I'd heard a phone ring at the theater, off-Broadway or on. Maybe I've just been enjoying an unusual streak of good luck, and audiences elsewhere are running rampant. But I don't think so. Most of them, I believe, are more like the guy next to me at "Offices": eager to be present in the moment, and trying their best not to ruin that moment for anyone else.

There are several different ways to crunch the 2009 Tony Awards numbers, but each of them strongly suggests that Broadway remains a man's world.

If you look at last night's winners in all 31 categories, including the special noncompetitive Tonys bestowed by the Tony Awards Administration Committee, women won 25.8 percent of the time. Wretched, yes, but things get worse from there.

If you consider only the 27 competitive categories in which Tony voters cast their ballots -- and if you figure, for the purposes of this number-crunching, that it was Liza Minnelli ("Liza's at The Palace") rather than her producers who won the award for special theatrical event -- the figure goes down to 22.2 percent.

And what if you take out the gender-designated categories, the ones in which actors are pitted against actors and actresses against actresses? That's when it gets very ugly indeed. Of the 19 competitive categories that aren't restricted by gender, women won two: a paltry 10.5 percent. That's with Liza still in the equation. (Whenever someone asks whether we still need separate awards for actors and actresses, my head quietly explodes. This is not the only reason, but it's one of them.)

A cynic would say the Tonys don't matter, but that ignores both the impetus for and the effect of the awards: money. It's not an artistic notion; it's a realistic one. Those statuettes translate into jobs, which matter quite a lot to people trying to make a living in the theater. Last night's winners suddenly have loads of people lined up wanting to work with them. And those winners are, by and large, men.

Yasmina Reza walked away with one of the evening's biggest plums, the best-play award for "God of Carnage," but she was the only female playwright among the nominees, and one of the very few female playwrights on Broadway this season. Nominated plays in the best-revival category were all penned by men.

In the eight design categories, women won nothing -- not a huge surprise, given that costume designers Jane Greenwood ("Waiting for Godot") and Nicky Gillibrand ("Billy Elliot") were the only females among the 33 nominees, making up a whopping 6 percent of the field.

Women fared better as nominees in the directing categories, which is a measure of some progress, even though they didn't win: Phyllida Lloyd ("Mary Stuart"), in her second Broadway outing, snagged one of the four play-directing nods, while Broadway newcomers Kristin Hanggi ("Rock of Ages") and Diane Paulus ("Hair") got two of the four nominations for best direction of a musical.

Elsewhere, Karole Armitage ("Hair") filled one of the four choreography slots, while Dolly Parton ("9 to 5") and Jeanine Tesori ("Shrek") were nominated for original score.

Is the rarity of women among the nominees and winners reflective of an absence of talent, a lack of desire to work on Broadway, or a scarcity of women graduating from the playwriting, directing, design or composition programs in American conservatories? Of course not. But compare the credits in a Broadway Playbill with the credits in a program for an off-Broadway, regional or off-off-Broadway show. Chances are you'll see more women where the pay and prestige are lower.

Yesterday afternoon, for example, I went to Ensemble Studio Theatre's annual marathon of one-act plays. EST is a famous incubator of talent, both established and emerging, and it's a valuable credit in an artist's bio. But it's hardly lucrative work. Six of the 10 plays in this year's marathon are written by women (among them Kia Corthron and Leslie Ayvazian); seven of the 10 directors are women. Of 37 roles, 22 -- 59 percent -- are played by women. The two costume designers, the set designer and one of the two lighting designers are all female.

Numbers like those simply aren't seen on Broadway, as a stroll through the Internet Broadway Database readily illustrates. It's no wonder that women win so few Tonys, given how little high-profile, high-paying work they're hired to do.

Those figures won't improve until women get more Broadway gigs in the first place. As always, however, the deck is stacked in favor of Tony winners and people with Broadway shows already on their CVs. Credits beget credits, and when awards are won, work is sure to follow. Which makes it a whole lot easier to earn a living -- a privilege that shouldn't be disproportionately reserved, even inadvertently, for the guys.

Facing funding cutbacks that would drastically reduce services, the New York Public Library is in the midst of a fierce campaign to articulate its value to the community. That effort now gets a serious shot in the arm from video testimonials by celebs including Amy Tan, Barbara Walters, Malcolm Gladwell, Bette Midler, Nora Ephron, Bill Irwin, Mike Nichols, Ellen Burstyn, Colson Whitehead, Tim Gunn and Jeff Daniels. It's unlikely that many other towns could round up a similar roster -- but as libraries all over the country confront the threat of shrinking budgets, they can find inspiration for their own counterattacks in the NYPL video.

"Whenever I hear the words that libraries are being cut back, I feel like people's lives are being cut back ... in a very real way," Gladwell says.

"Stand up and bang on a pan loudly for your public library," Mario Batali exhorts.

Indeed.

A.R. Gurney voyaged yesterday to the lush, leafy heart of WASP country -- Westport, Conn. -- to speak about his work in front of an audience that had just seen his 1974 play, "Children," at Westport Country Playhouse. The playwright talked about the new ending he's given it, how he manages to draw such juicy characters for women, and his need to write every day.

WASP-family classics like "Children" are a far cry from some of the prolific Gurney's recent work, including political plays that sometimes hold the mirror up to theater in general and Gurney's own oeuvre in particular. But the bite that complacent audiences are too likely not to notice in his dramas has always been there.

Mentioning Nancy Drew in a crowd of bookish women is a catalyst for rhapsody. Sonia Sotomayor's Supreme Court nomination, with its nod to her childhood love of the girl detective, has launched passionately fond recollections by fans, who find among their ranks not just Sotomayor but Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Those who never read the series as kids, or never got into it, find the passion of Nancy Drew admirers puzzling, but trust us: It's not about the writing.

June 1, 2009 11:33 AM

| Permalink

Kate Atkinson, Garrison Keillor and the horror of putting a book out there for other people to read.

June 1, 2009 11:28 AM

| Permalink