Great Shakespeare plays take the color of their surroundings – if the production is doing its job, and Broadway’s new King Lear is accomplishing that.

But then how could any alert, modern Lear production avoid the current parallels with lines such as these?

“’Tis the time’s plague when madmen lead the blind.”

“Get thee glass eyes and, like a scurvy politician, seem to see the things thou dost not.”

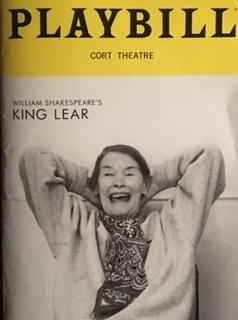

The theater world is inevitably referring to the production now in previews at the Cort Theatre as “the Glenda Jackson King Lear”, because the great 80-something actress is taking on the title role in Shakespeare’s greatest and most horrific play. But, as boldly re-conceived in modern dress by Sam Gold, the production is both all about her and everything else as well.

I would venture to call it King Lear in the time of Trump. But I’ll leave more definitive pronouncements to Broadway critics when the show officially opens in early April. This is not a review. It’s a primer.

The production is not a transfer of the Old Vic production in London in which Jackson starred a few years ago; it’s something new that’s still getting on its feet – with an interesting mixed-gender cast. Jane Houdyshell, for example, is the Earl of Gloucester. That’s more radical casting than putting a female in the title role since, as Jackson has pointed out, gender matters much less, if at all, the more one advances in age.

The most radical element of the Jackson casting is her size. She is quite petite, even though her hands and voice seem to belong to a much more physically imposing Lear. But in answer to the first question that comes out of everybody’s mouth, she plays Lear as neither male nor female. She just plays Lear.

The production seems built around that physicality, as Lear becomes the single, wavering, hobbled remnant of an old civilization that’s about to be engulfed by the forces of complete lawlessness. Lear may not represent a great or noble civilization; he/she/it is hardly the most evolved ex-monarch. But he represents order – and an order that’s better than none at all.

Unlike some production I’ve seen, the three daughters are equally civilized in the first scene. Sure, Regan and Goneril are playing up to their father’s vanity in a way that Cordelia famously does not. But the two sisters seem alarmed that the Cordelia has flamed out at a crucial moment, and motion her to sit back next to them while they do a bit of damage control.

Of course, that doesn’t last, as the characters slip into an all-controls-are-off world of no consequences, when people lie, betray, kill and screw whomever they want because they can get away with it. Over the last two years in the United States, one has become so accustomed to outrage-du-jour – not in a jaded or hardened way, but just used to it. This King Lear shook me out of that – perhaps because the production has a Brechtian coolness that allows compassionate emotional involvement, but to the point that any individual’s emotional anguish blots out the horror that the entire world of Lear has become.

I’ll end by expressing adoration for Philip Glass’s incidental music score, which is played by an onstage string quartet that sometimes stays in the background but is also moved around the stage at various points to participate in the action. His songs manage to sound both Glassian and Shakespearean. He’s always been a great collaborator, whether with director Robert Wilson or with the melodies of David Bowie as the basis for symphonies. And this collaboration is absolutely among his best.

[…] Great Shakespeare plays take the color of their surroundings – if the production is doing its job – and Broadway’ new King Lear is accomplishing that. But how could any alert, modern Lear production avoid the current parallels with lines such as “‘Tis the time’s plague when madmen lead the blind” and “Get thee glass eyes and, like a scurvy politician, seem to see the things thou dost not.” – David Patrick Stearns […]