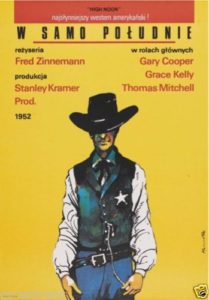

NEW YORK –  High Noon is a great movie, but does it immediately jump to mind as a story that’s ripe for re-evaluation and revision?

High Noon is a great movie, but does it immediately jump to mind as a story that’s ripe for re-evaluation and revision?

The 1952 original was a superior western, thanks to its strong psychological and political underpinnings. Those are the elements refracted in the new Axis Company stage adaptation, and they speak with remarkable specificity to 2018. Is there any way out of the cycle of justice, revenge and violence that is etched so clearly in this stage version? Not in a world where criminals promise prosperity.

The same plot lines are there: An Old West marshal (the Gary Cooper role) is about to retire with his Quaker bride when he’s told that a criminal he had sent away is now out of prison and headed toward town with revenge on his mind. As the townspeople abandon the sheriff amid the impending gunfight, the film version becomes a parable of the anti-Communist witch hunts of the post-war Joseph McCarthy era, when great Hollywood talents were blacklisted without much in the way of due process. Friends and colleagues protected their own interests by cooperating with a government that clearly wanted names of supposed Communists, with minimum regard for guilt or lack of it. The film’s July 1952 release came only two months after Lillian Hellman’s famous refusal to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee – a coincidence, to a certain extent, though such ideas were in the air.

The West Village-based Axis Company, under the direction of Randy Sharp, has a history of finding new meaning in pop-culture artifacts. This was my first encounter with the company; I was prompted by knowing the set designer and by my personal curiosity about the company’s facility, the basement theater at 1 Sheridan Square. It was inhabited in the 1980s by Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, which wasn’t actually ridiculous but did paint its theater in extravagantly chaotic psychedelia.

Now the place looks respectable. Ludlam (who died of AIDS in 1987) achieved brilliance in what was essentially garage theater that rejoiced in its improvisational haphazardness. Axis is somewhat the opposite, with its cast of ten (huge by off-off-Broadway standards) and handsomely composed black-white-and-gray stage pictures that were all of a piece. The script (apparently adapted by Sharp), the line readings, the plain period costumes (by Karl Ruckdechel) and the all-white set (by Chad Yarborough) might not have spoken the way they did if examined separately; together, they achieved a theatrical fusion, pared down to essentials, with even color at a minimum. Meanwhile, a subtle sense of forward narrative was maintained by the increasingly bright noonday sunlight seen through the cracks of the white set. The package was strong enough that comparisons with the film weren’t even on the table.

But the ways the story was tweaked are a major point of interest. The marshal’s decision to stay behind and defend the town wasn’t idealistic; it was common sense: if he didn’t stay behind and face the killers coming back for revenge, he would be running from them all of his life. Die now or not, but get it over with. The townspeople turned away from him not primarily out of fear and self-preservation: before the killer had been sent off to jail, the town has been far more lively and prosperous, and the populace wanted that back.

The casting of Brian Barnhart in the Gary Cooper role went against the heroism of the movie. A fine actor, Barnhart effectively projected the simmering anger and anxiety of his beleaguered state. I could never put myself in Gary Cooper’s shoes, but I can see myself in Barnhart’s.

Slowly, though, the play’s hold on reality drifted. Everybody is in high anticipation over the arrival of the bad guys on the train. Then we’re told that the train doesn’t always stop at this small town, even when flagged down. Are we in some sort of No Exit netherworld? Are the bad guys really coming?

The ensemble acting maintained a sense of truth amid such abstraction with line readings that put any number of moments in abrupt, sharp focus. The staging had a certain formality that suggested an element of ritual. After all, this story is cyclical, a constant churn of justice and the lack of it.

Then there’s the question of what is justice. Best to be virtuous and poor or somewhat corrupt and well-off? Timely thoughts, those. Especially in 2018, when the White House is inhabited by a businessman who may be an inept president but has presided over a sky-high stock market.

Yet there was no gunfight. The show stopped just short of that, and some viewers will find that decision unsatisfying theatrically. I found the effect Brechtian, offering no release from the issues at hand. Any traditional ending would suggest that justice of some sort wins out. Instead, we saw the cycle of violence that would seem to be unbreakable. Every act of justice comes with a backlash that makes violence (even when not wanted) seem inescapable. The cacophony of gunfire that was an overture of sorts to the first scene suggests that this cycle is greatly enabled by the availability of weapons. So High Noon became a dense, provocative, complicated nexus of ideas – the sort that’s possible off-off-Broadway.

Performances are Thursday through Saturday, running through March 24. Information: www.axiscompany.org

[…] High Noon adapted for the stage, speaking sharply to 2018 and with no exit High Noon is a great movie, but does it immediately jump to mind as a story that’s ripe for re-evaluation and revision? … read more AJBlog: Condemned to Music Published 2018-02-21 […]