Those who like theater that’s epic, brainy and political couldn’t have had a more irresistible ticket than A Room in India – no matter how expensive it was.

Théâtre du Soleil, the Paris-based crucible headed by director Ariane Mnouchkine, has a history of indelible appearances at the Lincoln Center Festival and the Brooklyn Academy of Music. One need only see Mnouchkine’s name and you’re there, there, there.

Yet the four-hour A Room in India, which plays through Dec. 20 at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, had something like a 20 percent audience-departure rate at intermission last Thursday when I attended. Some departed without deliberation: with not a word exchanged between theater-going couples, their coats and scarves came on. And they were gone.

Don’t think I didn’t consider doing the same. Was I disappointed? That doesn’t cover it. No, this piece roused a special kind of anger that comes with feeling like a culture victim (the Thomas Adès opera The Exterminating Angel did much the same), when artists who should know better betray an audience’s accumulated trust with work that shouldn’t have gotten past the first-draft stage.

I stayed. And though I wasn’t glad to have paid $91 in the wake of my Philadelphia Inquirer layoff, I was glad I made it to the end. Mnouchkine admirers know they must wait for an emotional payoff. Broadway theater audiences expect every scene to crest; opera audiences can wait a half hour or so. But Mnouchkine distinctively blends a group-written text, a strong political backbone, and documentary elements with near-operatic emotionalism that converges into the best of all theatrical worlds.

Of course, you won’t always connect with an artist who is always pushing into new territory. And not every work will be a revelation. Devotees of the late dance-theater artist Pina Bausch have to admit that some of her work’s repetitiveness turns out to be merely repetitive. Granted, Théâtre du Soleil is a completely different animal, with devised scripts, shared artistic responsibility and, with any luck, checks and balances that Bausch didn’t have after a certain point.

Nonetheless, A Room in India was lacking dramaturgical self-awareness. On a certain level, the show was merely what it said it was: A Western theater company visiting India has its various challenges and quirks embodied by one Cornelia, who is sort of a worker bee charged with holding the company together. She’s awakened out of a sound sleep by either external crises or her own fantastic delusions. The show begins promisingly when she receives a phone call that her King Lear-like leading actor has been arrested drunk, disorderly, and naked on top of a public Mahatma Gandhi statue.

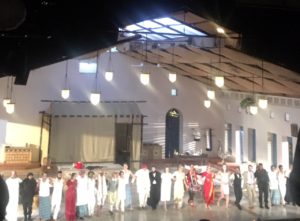

From there, she lives her own kind of Groundhog Days, each one starting the same way, with a fateful phone call that might be real or might be a dream, and carrying news such as her daughter being converted by some jihadists. All sorts of weather effects come roaring in from the side windows. The documentary elements come in the form of sagas that are seen in extended chunks, from elaborately staged and costumed scenes from The Mahābhārata to a send-up of the epic film Lawrence of Arabia. The modern scenes encapsulated issues we’re all facing in the 21st century. The sagas suggest where it all came from – most especially the suppression of women. Will we ever escape our own toxicity?

With such important issues unfolding over the sort of huge stage that warranted the expanse of the Park Avenue Armory, you might wonder where the problems lay. Well, theatrical pacing was fitful. The acting was manic, physical and jokey in ways that never showed you the inner life of the characters. You needed to care for Cornelia but were given little reason to, especially with all her manic physicality.

The juxtaposed elements – real-life story, the dream world and ancient legends – had a “meta” relationship with one another. Yet no one element was presented with the sort of clarity that allowed you see see how one was riffing off of another. In other words, how can you appreciate a “meta” reaction when the source of it is unclear? New York audiences have seen The Mahābhārata (the Sanskrit poem about dynasties rising and falling with much philosophy along the way) but they haven’t studied it. And the “meta” elements didn’t stop there. Dressing rooms were located underneath the seating area in full view of the incoming and outgoing audience – and fancifully decorated.

Ultimately, the various elements took on an emotional impact that was indeed touching, suggesting that this was in fact an intimate story that didn’t belong in such a huge venue, with some viewers too far away to feel the heat of what may have been happening onstage.

But that heat was diluted by the production’s own theatrical mechanism. The ending was a political sermon – yes, a straightforward, facing-the-audience sermon, in which the speaker was struck down repeatedly – preaching peace, love and understanding. At one point, somebody asks if the all the theaters of the world were burned or closed, would it matter? Obviously, yes, but I think Mnouchkine is working too hard to prove that. And this isn’t a problem only with A Room in India.

You can’t blame artists when their rage over current events is so close to the surface of their art. But when does social rage become a public rally rather than something artistic? (And I ask this as someone who is completely sympathetic to views presented in A Room in India.) What Mnouchkine was after was perhaps more clearly codified in her film Les Naufragés du Fol Espoir. Its core story concerns a ship rounding Cape Horn in search of riches, and its passengers and crew being shipwrecked on a snowbound island that they attempt to colonize. However, the story is told by a silent movie that’s in the process of being shot while World War I is unfolding. Some of the key actors are in danger of being drafted.

The movie’s story on the castaways’ island turns into a parable of greed usurping humanity. (Ever heard of that before?) But the storytelling has two layers of jokey artificiality – the quaintness of silent film technology and the silly lengths they will go to in creating effects that are probably turn out cheesy anyway. Yet somehow, artificiality yields truth. Partly through effective use of cinematic closeups not available in A Room in India, you get under the skin of the characters in ways that make the story emotionally affecting. Ultimately, though, the social commentary robs the story of its texture – maybe not to the extent of A Room in India, but there’s only so far you can go into the hearts and minds of the characters because the film doesn’t want you to forget about the issues at hand.

And that, perhaps, is why these two pieces will perhaps have only momentary relevance. But that may be what devised theater is: Taking the current pulse of this moment in history, posterity be damned.

[…] A Room in India at Park Avenue Armory: A theater titan stumbles? Or fights back? Those who like theater that’s epic, brainy and political couldn’t have had a more irresistible ticket than A Room in India – no matter how expensive it was. Théâtre du Soleil, the Paris-based crucible headed by director Ariane Mnouchkine, … read more AJBlog: Condemned to Music Published 2017-12-19 […]