He doesn’t look much older than when he was 60. But he’s showing his age in a way that true artists do. His 2014 piece, Greenwich Village Portraits, is one of his very best.

He doesn’t look much older than when he was 60. But he’s showing his age in a way that true artists do. His 2014 piece, Greenwich Village Portraits, is one of his very best.

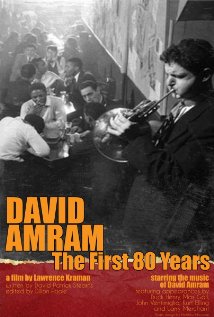

David Amram has led multiple lives simultaneously. He’s a jazz musician able to improvise an actual song on the spot, the master of many ethnic and folk musics who plays at Farm Aid concerts (and fits in), but most importantly, is a composer of classical concert music. Maybe I was too bewildered in past years to put it all together. Then I was asked to work on the documentary film David Amram: The First 80 Years, produced and directed by Larry Kraman.

During that time, I learned about even more worlds he has inhabited, such as his life in post-war Paris, and his longtime creative partnership with Jack Kerouac. The two would improvise together, Kerouac with words, Amram with his French horn. He was at the center of what came to be known as the Beat Generation but also wrote a handful of scores for life-changing films such as The Manchurian Candidate and Splendor in the Grass. He commemorates people so often in his music – sometimes his creative life looks like an extended Enigma Variations – I was mildly shocked that he has a 1960 piece simply titled Violin Sonata. How did that happen?

In the Dec. 21 concert at New York’s Theater for the New City – titled “Back to Where It All Began: David Amram at 85” – he was still commemorating, but I’ve learned to only note that in passing en route to the deeper content of his music. So concerned has Amram been with reaching out to the world (rather than turning inward like so many of his 1960s modernist contemporaries) that you can say, “I got the piece” and not go back to it even though there’s much more to go back to. One of his richest orchestral works is a set of variations “This Land is Your Land,” though I fear that not so many people have looked beyond his inventive permutations of the famous melody.

Now, the new piece. Greenwich Village Portraits, is written for saxophone and piano, the three movements being portraits of playwright Arthur Miller, singer Odetta and author Frank McCourt. To me, the only thing these subtitles explains is the presence of Irish folk melodies in the McCourt movement. The rest, to me, show him returning to the rich harmonic world of his Splendor in the Grass film score.

Why not? More music easily grows out of that soil – though it’s now more elegiac, not as intent on resolution, and encompassing a greater emotional range, though with an ease that doesn’t require him to reach in numerous different directions to do so. The music has a solid, central personality, a wonderful sense of lyricism in ways that are confidently integrated, at every turn, with the rest of the piece. It feels wonderfully distilled, and it issues an open invitation to be heard again (especially with saxophonist Kenneth Radnofsky). Word has it that an Amram Chamber Ensemble is being formed that will prompt more new music from him. After all, he is in a race against time. For years, he has vowed to celebrate his 90th birthday by enrolling in dental school.

Here are two of my favorite stories that David tells. One involves Eugene Ormandy, Native American music and jazz, and the other Allen Ginsberg and Robert Zimmerman…I mean Bob Dylan:

https://youtu.be/B2v_VdTUG0Y

https://youtu.be/sbaSnDEzTeU

What a joy to be able to see you and hear you via this video, David. I often brag that I know David Amram, although I wish I could know you better. I greatly admire your fabulous talents,but just as important, I admire you as a person. Please continue in good health!

Lew Petteys

Wow…thanks. You’ve made my week, my month….