Harry Partch’s biggest and most accomplished work, Delusion of the Fury, long stood alone like some singular Gaudí-designed cathedral in a desert. But now, 46 years after its premiere, it appears at Lincoln Center Festival with a like-minded artistic community having grown up around it. Strange no more, the music maintains its singularity while feeling familiar.

Harry Partch’s biggest and most accomplished work, Delusion of the Fury, long stood alone like some singular Gaudí-designed cathedral in a desert. But now, 46 years after its premiere, it appears at Lincoln Center Festival with a like-minded artistic community having grown up around it. Strange no more, the music maintains its singularity while feeling familiar.

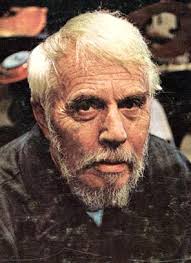

Long considered the ultimate American maverick composer, Partch (1901-1974) resisted the typical compositional norms of the mid-20th century, inventing his own instruments – often out of discarded junk like oil drums and automobile hubcaps – that could play a 43-pitch microtonal scale, the likes of which composers before him had only occasionally dreamed about.

Yet Partch didn’t like being called a revolutionary. He claimed to be an evolutionary. And on Thursday’s opening night of Delusion of the Fury at City Center, played by the Cologne-based Ensemble musikFabrik, he couldn’t have been more right.

I wonder if the audience’s considerable hipster contingent was disappointed that the piece wasn’t crazier. At least they had the Partch mythology to tap into: Having lived as a hobo during parts of The Great Depression, he can be seen as a sage truth-teller who had seen life from the bottom up. I don’t put a lot of stock in that (more later), but some may find that context interesting.

As fluid and even effortless as the piece sounded, the act of integrating Delusion of the Fury into today’s larger musical world required extraordinary effort. Partch’s original instruments have been falling apart for some years now, and the Cologne group meticulously recreated an entirely new set of them, many of the members having learned to play the instruments for the occasion.

The production was adapted and staged by Heiner Goebbels, the multi-discipline composer who has written a concerto for sound sampler (among other things). For Partch, he created a stage environment with a wading pool plus plastic inflatable foot hills and a snow-covered mountain to frame the percussion and keyboard instruments.

The performance was such that analysis of this mildly esoteric piece wasn’t needed. You could simply revel in the sound. The score has a distinctively West Coast sense of self-expression over formal rigor, though never is Partch at a loss for creating compelling musical ideas – ideas that appear in through-composed modules, some of them vocal, with motifs repeated like incantations.

The central leitmotif is a flourish by a cimbalom-like instrument that, though its expanded scale, conveys extravagant delirium, exalting in its liberation from the usual 12 tones. Specially built organ-like instruments were parked on each side of the stage. Any number of percussion instruments added to the hugely exhilarating effect when the ensemble was in full cry, with the occasional addition of splashing water during the piece’s series of dramatic incidents.

One such incident has a woman looking for her lost child and questioning a justly paranoid hobo. More compellingly, a Samurai-like warrior who has killed many opponents confronts the ghost of one such victim.

Contrary to the principles of “outsider art” (few antecedents, no descendants), Delusion of the Fury was long explained as a unique mutation of Japanese Noh theater. Now, it easily sits next to Steve Reich’s ecstatic percussion-based works such as Tehillim and Meredith Monk’s textless vocal pieces (especially her opera Atlas) that find their way to your inner life with a contemplative theatricality. Add Einstein on the Beach to that list. Of course, Partch pre-dated most of them, but his music has been so seldom heard (the recordings made under the composer’s direction can be rather demure, capturing maybe 60 percent of the impact) that it’s hard to imagine Delusion of the Fury had direct influence.

Such ideas – microtones, Asian-influenced, non-linear theater with percussion-based music – were in the air for some time; Partch simply crystallized them earlier than most westerners, and maybe not in ways that were all that clear during much of his lifetime. Partch now makes an especially fascinating counterpart to George Crumb, who created a similarly singular sound environment with existing instruments, though played in non-traditional ways. But while Crumb emphasizes color and sound shapes, so much of Partch is about notes sounded in fairly traditional ways, even if you’d never heard any such collection of notes together. Tan Dun also comes to mind, with his use of unorthodox scales and sounds achieved through found objects like rocks and water.

Such ideas – microtones, Asian-influenced, non-linear theater with percussion-based music – were in the air for some time; Partch simply crystallized them earlier than most westerners, and maybe not in ways that were all that clear during much of his lifetime. Partch now makes an especially fascinating counterpart to George Crumb, who created a similarly singular sound environment with existing instruments, though played in non-traditional ways. But while Crumb emphasizes color and sound shapes, so much of Partch is about notes sounded in fairly traditional ways, even if you’d never heard any such collection of notes together. Tan Dun also comes to mind, with his use of unorthodox scales and sounds achieved through found objects like rocks and water.

The aforementioned romanticism of Partch’s vagrant life felt mostly irrelevant to Delusion of the Fury. Prior to the concert, Partch’s memoir Bitter Music was selectively read by the so-called sound poet David Moss, giving accounts of the lice-infested life of Great Depression work camps. Maybe I was turned off by Moss, who animated the text with what amounted to cartoon-character voices that deflected the meaning of the content. Also, my own experiences dating back to my counterculture days – hitchhiking across the country, sleeping under noisy highway bridges, making myself at home in abandoned buildings – were more about hippie chic than achieving poetic revelations. Clearly, Partch had a social conscience, hobo or not. The compliment to Partch’s music is this: It doesn’t need any maverick cool, but now stands solidly on its own.

Fascinating stuff, as usual with your postings. Thanks, David.