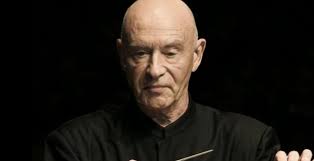

Only weeks ago, Christoph Eschenbach’s new recording of Paul Hindemith orchestral works came bubbling through my speakers with a kind of sparkling animation and buoyant rhythms one rarely hears in typically machine-tooled performances of this ultra-contrapuntal composer.

“Eschenbach got his groov e back,” I thought. The orchestra was NDR Orchestra, which he has been returning to, having been its chief conductor 1998–2004. Of all the orchestras he has led since the Houston Symphony Orchestra (1988-1999), NDR seemed to understand him best, perhaps because of its roots in the school of subjectivist interpretation that died out after World War II but seems to have survived within Eschenbach.

e back,” I thought. The orchestra was NDR Orchestra, which he has been returning to, having been its chief conductor 1998–2004. Of all the orchestras he has led since the Houston Symphony Orchestra (1988-1999), NDR seemed to understand him best, perhaps because of its roots in the school of subjectivist interpretation that died out after World War II but seems to have survived within Eschenbach.

Then came the news from Salzburg: In the birthplace of Herbert von Karajan, Eschenbach had been booed at the Cosi fan tutte opening night, followed by accusations by the critics of a haphazard performance. Since then I’ve combed the web, hoping to hear the broadcast, only to find strenuous commentary, including a Philadelphia Orchestra player who said Eschenbach, during his 2003- 2008 tenure, was often under-prepared. Others speculated that the Salzburg incident was trumped up by critics.

More likely, it was a simple a matter of time – and not enough of it. With Eschenbach, there seems never to be enough of that.

He stepped into the Salzburg production upon Franz Welser-Most’s departure. But prior commitments – in Australia – meant he flew in only days before the opening. What conductor – 73 years old or otherwise – could pull that off? Far East jetlag is tough: You wake up feeling that your blood has turned to tar. And conducting Cosi fan tutte in that condition? A long eventful ensemble opera with many intricate moving par ts?

ts?

We’ll never know whose fault that was. Having observed Eschenbach at close proximity during his Philadelphia years, his psyche remains a mystery to me – not surprising given formal distance that was necessary during those fraught times. But he clearly thrives on filling major gaps left by departed colleagues. When James Levine was unable to continue with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Eschenbach was darting around the East Coast between rehearsals and appearances in with his National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C. During a phone interview at that time, he said, “It keeps me young.”

To his credit, he isn’t one to take on these starry engagements by canceling pre-existing ones. Shortly before his Philadelphia tenure started in 2003, departing music director Wolfgang Sawallisch fell ill and was unable to lead the orchestra in a North and South American tour. Eschenbach could’ve scored a needed public relations coup by stepping in – especially since his appointment was regarded by some musicians with trepidation. And he had to be aware of that. But he was booked up with previous commitments. End of conversation.

And what kept him in Australia when he would’ve been better off preparing Cosi in Salzburg? An Australian youth orchestra, according to reports – clearly an act of giving back. Few musicians at his level are so generous with their time. During one of Eschenbach’s returns to Philadelphia after leaving the orchestra in 2008, he made a guest pianist appearance in Dvorak’s Piano Quintet Op. 81 with one of the lesser string quartets in town – playing the performance in the early evening prior to conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra the same night. He didn’t have to do that.

As a person, the Philadelphia musicians tended to like him, sometimes quite a lot. He exudes grace and kindness – which may have been part of the problem in a rough, tough town where vulnerability is not a virtue. But numerous professional reports that came my way during his music director years – being stuck in an elevator with one of those Fabulous Philadelphians meant getting an earful – suggested Eschenbach often tried to steer an ocean liner with the agility and spontaneity of a speed boat. And maybe he didn’t entirely know how to do that.

He failed to prioritize because he wanted it all, and was probably used to getting it in his earlier career as a pianist, when practice time was virtually unlimited. But a lively rehearsal technique with orchestras did not come easily to him. Most idiosyncratically, he rehearsed an orchestral version of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden quartet so much that there was little time left for Zemlinsky’s Lyric Symphony – a piece largely unknown in the U.S. At one point, the influential Norman Lebrecht was in town to promote his newest book and went to hear the orchestra on one of those nights. I remember coming out of that same performance thinking, “Any concert but that one.”

Eschenbach is a gambler, both in his interpretive choices and his taste for maverick collaborators. Tzimon Barto can be an interesting pianist, but he following a willful, inaccurate Brahms concerto performance with an onstage reading of his own poetry in lieu of the encore that nobody wanted. Ccringeworthy, to say the least. When Marisol Montalvo sang Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, her conception and command of the language was extraordinary but the voice wasn’t right. Their recording was never released. Bad luck also plagued the live Mahler recordings made in Tokyo’s Suntory Hall on tour. He requested a patch session that couldn’t be scheduled.

The core problem, as told to me, was conducting mistakes. He had his share, but Eugene Ormandy is said to have had many, many more. In fact, Ormandy was so unable to conduct complex meters that he had The Rite of Spring rewritten in 4/4 and regularly got lost in Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, one of his signature pieces. Karl Bohm’s live Cosi fan tutte recording from Geneva has a near-train wreck in the military chorus scene, so far apart are singers and orchestra. Even Simon Rattle has said, “Nobody hires me for my clear beat.”

What does one hire Eschenbach for? Vision, and one unlike any other, such as in the Ondine-label Hindemith recording, which finds a softness, lyricism and poetry in the Symphonic Metamorphosis and the Violin Concerto – works that previously seemed severe and cerebral. This is a significant step forward in Hindemith performance.

Though Eschenbach the pianist tends to be a pristine classicist, Eschenbach the conductor is much the opposite, a throwback to the more subjective approach of Wilhelm Furtwangler. In his core repertoire, the Mahler Symphony No. 6 lives fearlessly in the abyss. His Dvorak Symphony No. 9 (“New World”) is emotionally centered on the nostalgic second movement: Throughout the symphony, chord resolutions seem to ache for home – and the repose of finding it. This is from a man who, as a child, watched his grandmother die in a quarantined refugee camp after World War II.

Eschenbach once told me that he has no comfort zone. I believe it. He also doesn’t have a safety net. He doesn’t necessarily conduct the performance he rehearses – which may in fact be the definition of a performance. But he has no objectivist grid to fall back on. When musicians aren’t conceptually on board with him, his ideas can seem like mannerisms. And for his ideas to sink into an orchestra, the main ingredient is time.

“After a while, he just gets inside your head,” said one of the Houston Symphony musicians in a casual conversation. And no doubt that happened because Eschenbach gave Houston – unlike Philadelphia, where he was sometimes gone for months in the middle of the season and always seemed like a visitor – lots of time. He truly lived in Houston. His tailor was there. His tenure was a decade plus. And when his thinking meshes with his musicians, conducting mistakes are more easily covered. Spontaneous flights of inspiration are more easily followed.

When most conductors have a bad night, they’re simply dull. With Eschenbach, a bad night means that his ideas are only half-realized and not at all clear to audiences or critics. Might that have been the case at the Salzburg Cosi fan tutte? An after-opening report suggests that the production has come together, and Eschenbach is doing just fine. But the damage to the reputation of this unlucky musician is already done.

A most fascinating and compelling read: on one level, a real insight into the stakes of high-level music making, written with an insider’s knowledge and a wonderful flair for haute vulagrisation.

But there is more.

There are two absolutely classic sentences: ‘Ormandy was so unable to conduct complex meters that he had the Rite of Spring re-written in 4/4’. And: ‘[Eschenbach] doesn’t conduct the performance he rehearses: which in fact may be a definition of performance.’

There is a fallacious received idea that there exists a whole realm of Platonic ideas into which we must obligatorily dip, as one might consult an encyclopedia, if we are to perform spiritual tasks like creating a musical performance, understanding an idea, or interfacing with the learning experience of a foreign language.

But surely A.N. Whitehead was closer to the truth when he saw all life, including metaphysical life, as ‘process’. Processes are that with which we can transform the donnees we find around us, and to which thereafter we will have contributed a very small iota. Everything is in flux, and (although Whitehead pre-dated Einstein) effects are quantum, something Patrick’s second quote given above succinctly defines.

In a concert there are not two actors (the performers and the music) but surely three: the music, the interface upon which musical thoughts are focused (and with a great orchestra that is akin to the focusing of a laser beam) and the resulting (what one can only call) ‘idea’ – which briefly flickers (as Plato’s cave) and comes to rest in Whitehead’s repository of achieved processes, which he also likened to God.

We are thus all parts of the mind of God, and great music – even [maybe especially] new music – needs to contract into that reality, find somewhere that well-spring, that flow: not just vaguely capitalize on the old “pre-Reformation” doctrine that art is just me convincing you of my idea (however arbirary ; or (simply) about my idea about Beethoven. Hence my huge cavills with all positivisms and – above all – what I can only call the heresy of post-Modernism.

No: it’s far more magical than that; and to realize that magic is to appreciate Tippett’s famous definition of the artist’s vocation (when discussing the subconscious) in ‘Moving Into Aquarius’ – [to create] “images of abounding, generous beauty”.

Anything less than that is not enough.

Clicking on the Martin Smith hyperlink leads to

http://martinenglish.co.uk/

Well thanks, it does. But I am working on a better website which I hope to have running soon, which will look at my teaching experience and views on pedagogy and slightly dissenting views about certain received ideas. Clearly there are parallels between language learning and music learning and the presentation eg of poetry or drama and that of say an art song or an opera. I am just a bit concerned that we really search for the authentic, as great musicians such as Eschenbach and Pires and Barenboim clearly do. But even the smaller talents can have the right attitude and seek to make a true contribution.