November snow was still piled up on the foot path of the Brooklyn Bridge one recent Friday, but not enough to stop a pair of guys from stomping through the slush on a midnight, across-the-bridge run, for which they were both, incongruously in 30-degree weather, shirtless.

November snow was still piled up on the foot path of the Brooklyn Bridge one recent Friday, but not enough to stop a pair of guys from stomping through the slush on a midnight, across-the-bridge run, for which they were both, incongruously in 30-degree weather, shirtless.

The rules are up in the air now. Weather events that once seemed specific to different seasons (like the dead of winter) and distant states (like Florida) are appearing in anything but their proper places and turning New York City, among other locales, upside down.

At least the musicians seem ready for it. Drawn out of the woodwork by the John Cage anniversary year, or maybe emerging like groundhogs who sense their time is nigh, musicians seem to be living on the outer fringes more visibly and in increasing numbers – going not just well beyond the usual manipulation of notes, rests and harmony, but well beyond the actual use of sound. Two recent instances: The Latvian Radio Choir at Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival, and in the incidental score for Mies Julie, a South African adaptation of the August Strindberg play that was the hit of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and plays at Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Warehouse through Dec. 16 – and was the occasion for my surreal sighting of shirtless night runners on the Brooklyn Bridge.

In the background of all of this is Dog Days, the David T. Little/Royce Vavrek opera that knocked seemingly everybody for a loop in October at Montclair State University. The piece ended with an act of cannibalism characterized by an electronic crescendo that went on for at least ten minutes, continuing longer and shaking the building harder than anything I had ever experienced or imagined. Perhaps that’s the only way to dramatize a climax where starving family members return to the stage having eaten somebody, their faces covered in fresh blood. No heat-and-serve meals for this bunch.

Similarly, Mies Julie repeatedly immolates numerous rules that hold together that amorphous thing called civilization. Adapted and directed by Yael Farber, this Baxter Theatre Centre production from the University of Cape Town transplants Strindberg’s original time and place to perhaps the only modern locale where the play’s class distinctions can be as pungently and uncompromisingly portrayed as they were originally intended to be.

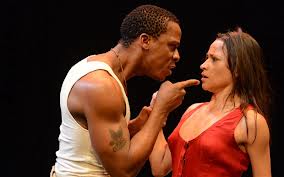

The power games between the privileged Julie, a wealthy Afrikaner landowner’s daughter, and the dark-skinned farmhand to whom she’s sexually attracted, can easily seem dramatically redundant and unlikely in their extremes almost anywhere except in a post-apartheid culture: The two of them are alternately scheming to run away with each other and threatening mutual homicide, partly out of shame for having considered such a socially unthinkable union.

Sexual matters are portrayed with such graphic brutality that I sometimes shielded my eyes, especially when the audience is shown one particularly gruesome theatrical illusion near the play’s end. When something goes so far to the fringe of human temperament, is music even possible? Only, perhaps, with a level of electronic sound that wasn’t technologically possible some 20 years ago.

Sound design and incidental music were inextricable in this collaboration between brothers Daniel and Matthew Pencer. At times, the music coming from the laptop at the side of the stage suggested a distant factory turbine – or possibly the very beginnings of a migraine headache. Such sounds later resembled a heartbeat, or a distantly tolling bell that suggested either somebody’s funeral or the arrival of something forbidding and inevitable. But the real wild card here was a tenor saxophone that was played with nothing but extended techniques, rendering fine shades of emotions manifested through various mutations of breathing or moaning or weeping.

Is it possible for something so poetically ambiguous to be so viscerally appropriate? It was here. Musical effects like this can bring the play’s emotional content together in a way that makes the difference between the success of a directorial concept or not.

Now the Latvians: The Nov. 16 program at St. Mary the Virgin had seven works, all radical in one way or another but too artistically consolidated to be called experimental. The chorus, directed by Sigvards Klava, began the concert – with Knut Nystedt’s Immortal Bach, a piece that piggy backs onto the Bach chorale “Komm, süsser Tod” (“Come, Sweet Death”) – positioned around the front of the church in ways that gave the illusion that the walls were singing. Then when Nystedt’s dense 20th-century harmonies kicked in, the individual bricks seemed to be singing.

The program also included György Ligeti’s famous, almost-classic 1966 Lux aeterna and Ēriks Ešenvalds’s neo-primitive Legend of the Walled-Up Woman. What was most striking, though, was a piece that truly came out of the side door, Anders Hillborg’s 1986 muo:aa:yiy::oum. If we haven’t heard this score until now, it’s probably because only a few choirs in the world can sing it – at least on a level that would allow you to actually apprehend the music.

As its title suggests, the piece has no text, just syllables that accommodate the composer’s desire to translate sounds from the electronic-music world to the human voice. Blipping, pulsating harmonies and rhythms that one associates with electronics made the transition to voice with complete success, and with much of the entrancing energy of the early minimalists.

But if you want electronic sounds, why torture a chorus into imitating them? In fact, there was no evidence of torture. The sounds themselves, which generally seem cool, self-contained and somewhat uninvolving in a purely electronic medium, were absolutely mesmerizing in their vocal manifestation – and, in passages where the sopranos reached for ultra-high notes that bordered on a shriek, had poetic implications you could contemplate for days.

It’s important to note that the electronic effects of Dog Days and Mies Julie drew at least some of their power from their conspiratorial relationship with acoustic instruments. The advent of refined electronic sound also raises the bar in terms of tapping the emotional power that comes when a given timbre is rendered with air-tight precision.

And that’s why, at the concert version of Wozzeck conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen with the Philharmonia Orchestra at Lincoln Center in Nov. 19, I often felt that I was hearing the score for the first time. Salonen’s ear for sonority is unlike anything I had heard before, even on the best recordings. The opera has its share of unspeakable acts, such as Wozzeck’s crazed murder of his unfaithful wife, that have been conveyed in the past with orchestral brute force. This time, hearing the exact nature of the orchestral sound greatly expanded the opera’s meaning.