main: May 2007 Archives

book/daddy is heading to New York for BookExpo and then to D.C., on yet another groundbreaking scholarly endeavor. In short, book/daddy will be hanging out with the Eastern elites, the publishing industry old-money intelligentsia -- like the guy at BookExpo one year dressed as a giant basketball.

Needless to say, these are primitive, dangerous territories book/daddy will be venturing into. He has no clear idea about wireless internet access. So postings this week and early next may get sporadic, interdicted or just plain desparate.

Send help. Send vodka tonics with limes.

Just saw Pirates of the Caribbean: The Third Time Will Drive You Off the World's Edge or whatever. This, by the way, seems to be our new civic duty on Memorial Day: See the biggest Hollywood blockbuster out there so we can set a new weekend box office record.

Just saw Pirates of the Caribbean: The Third Time Will Drive You Off the World's Edge or whatever. This, by the way, seems to be our new civic duty on Memorial Day: See the biggest Hollywood blockbuster out there so we can set a new weekend box office record.

God bless America.

Actually, I enjoyed the film -- in that smiling stupor occasionally jolted by yet another tremendous CG effect and pointlessly complicated plot twist. The nervous bliss that passeth all understanding, and which these movies are designed to promote. Seriously, I enjoyed it, although it seemed to me so stuffed with ... stuff that the filmmakers had lost all sight of the original film's pleasure.

Johnny Depp.

Not enough Johnny Depp was a serious shortcoming. And the scenes with multiple Depps didn't make up for that lack because it's Depp's Capt. Jack interacting with others that's funny. Depp pulling a little Depp on Depp is a bit pointless, and that pretty well sums up the film. By the way, if no one's told you, stick around for the end of the unbelievably long credit sequence. My family and I and maybe three other people in the entire theater had gotten the word.

But -- this IS a literary blog, after all -- the occasion of the third installment and the mad popularity of pirates these days have prompted me to divulge my one great Literary-Cinematic Commercial Idea, my Hollywood script-and-production deal that actually, I think, could be bankable and could work. Patent pending, copyright invoked, you've been warned, fifteen men on a dead man's chest, and all that federal statute FBI warning stuff.

Are you ready?

Amazing. Norman Podhoretz is the author and editor of a half-dozen books, probably thousands of essays. Still the big cheese over at Commentary magazine. Yet he doesn't recognize a dangling modifier -- or that it can make him sound foolish.

This is the very first sentence from the very first essay -- so you think someone might have noticed -- highlighted at the top of the new issue on Commentary's website:

"Although many persist in denying it, I continue to believe that what September 11, 2001 did was to plunge us headlong into nothing less than another world war."

Wouldn't you like to meet some of those people? The ones who persist in denying Mr. Podhoretz' belief in his own certitude?

In The New York Times Book Review, Steven Pinker reviews Natalie Angier's new book, The Canon: A Whirligig Tour of the Beautiful Basics of Science and uses the occasion to bemoan -- with good reason -- most Americans' pig-headed ignorance about essential scientific ideas and the horrid consequences this leads to.

It's a familiar cry, but one that Dr. Pinker delivers with verve and insight. Dr. Pinker advances a number of reasons for this entrenched ignorance, and some of these are familiar, too, such as the media's preference for the "newsy" and the "revolutionary," a preference that overemphasizes the supposed (and often illusory) breakthroughs over the accepted wisdom. I found Dr. Pinker's notion, however, that parents "grow their children out" of going to museums and into theater-going a little laughable, considering the dire and often utterly peripheral state of arts education in the United States.

But over at Edge, Paul Bloom and Deena Skolnick Weisberg offer some very different explanations for our resistance to basic notions in science. And it's not just Americans or even fundamentalist-yokel-Americans: "1 in 5 American adults believe that the Sun revolves around the Earth, which is somewhat shocking--but the same proportion holds for Germany and Great Britain."

Where does a critic's authority come from? Where does this guy get off saying the book I loved was a waste of wood pulp?

Where does a critic's authority come from? Where does this guy get off saying the book I loved was a waste of wood pulp?

And why should anyone listen to him?

The questions occurred to me while reading Richard Schickel's instantly notorious, flame-bait outburst against bloggers, "Not everybody's a critic" in the LA Times. Much of what Mr. Schickel grumps about is -- pace all of the outraged bloggers -- perfectly accurate. Reviews aren't just opinions, no matter how wittily and dismissively they're expressed. Much of what passes for literary criticism on the web is simply very loud likes and dislikes, often not very enlightening likes or dislikes, unsubstantiated and barely argued, if at all -- dragged down, perhaps, by the way the web inspires flame wars and insults. If Jessa Crispin (Bookslut) trashes another book -- like Don DeLillo's Falling Man -- while declaring her contempt for the work in question is so mighty and inviolate that she'll never stoop to reading the book, I'll stop paying attention to her judgment on most any book. And I heartily agree with her on many graphic novels. But the surly imperiousness does her no favors.

And Bookslut is actually one of the more interesting book blogs around. Think of the thousands of others.

The question of a critic's authority has nagged at me for as long as I've been a working critic (more than 20 years). It's nagged me because many of the conventional answers felt inadequate (he has a Ph.D., she wrote a book on the subject, that other guy writes for the Times). And although journalism doesn't permit much introspection, it does have a habit of hitting you with the same basic problems over and over until you solve them. Or ignore them entirely.

What follows, then, is my ploddingly pragmatic attempt (I apologize for its length) to work out where critics derive their authority to speak ex cathedra the way we do. And I do mean Pragmatic with a Capital P -- this attempt avoids any resort to critical theory because I repeatedly found those tools unhelpful when a caller was threatening to break my arm over what I wrote about his play. Instead, this essay focuses on what strike me as day-to-day realities of critics and readers, what happens between them in the course of a review and over time.

It's my apologia pro via critica -- a phrase which, by the way, this critic can't help noticing mangles Latin and Greek together.

Authority or just plain credibility as a reviewer was a pressing concern when I became the Dallas Morning News' theater critic in 1986 for the simple reason that I had never taken an acting or directing class, never studied theater as performance. To be sure, there'd been plenty of courses on theater as literature. My doctoral dissertation, if I'd written it, would have been on Samuel Beckett, and what I considered my master's thesis was on Hamlet.

But as theater people well know, there's a world of difference between the page and the stage. Love's Labor's Lost, Act IV, scene 3, has different characters entering sequentially. Each comes upon the previous character and spies on him reading aloud a love poem or letter. In turn, the spy finds a letter to read aloud (or reads his own sonnet) only to be spied upon by the next character happening by, and so on, until everyone is revealed as love-besotted fools. The first time one reads this scene, the contrivances and repetitions are just hokey, utterly silly without being clever. On stage, though, any halfway competent director and cast can make the scene charming or even uproarious. And if the director is inventive enough, the actors talented enough, the third or fourth time you see a production of Love's Labor's Lost, that scene can still be a delight, especially the happy anticipation, the mechanical certainty, that the last idiot simply must walk out onstage and fall into the same trap.

As a public relations writer for what is now known as Bass Hall at UT-Austin, I'd certainly gained some in-the-trenches theater experience. Working with the English National Opera on tour, Twyla Tharp and dozens of Broadway productions was a hands-on, backstage job, dealing with everyone from lighting crew to box office. But again, it's not the same as acting or directing outfront.

On the other hand, how many film critics have actually made a movie? It's the old Dr. Johnson line -- one needn't be a cook to know dinner is bad.

So what does one need to know? Where does a critic's taste, his authority, his ability to pass judgment, originate?

You can find my San Francisco Chronicle review of Richard Flanagan's The Unknown Terrorist over here.

Michiko Kakutani of The New York Times loved the book, along with quite a few other reviewers. So far, only one other critic besides myself (James Buchan in the Guardian) found it over-determined and noisy, to say the least. Here's a paragraph from the Chronicle review:

"Flanagan has fleshed out the bones [of Heinrich Boll's The Lost Honor of Katherina Blum] as a suspense thriller with a heart of bitter satire. Flanagan is the author of three rich, vivid novels -- the third one, Gould's Book of Fish, is extraordinary, an illustrated novel about colonial Tasmanian prison life told, as its subtitle has it, "in 12 fish." His prose may be less mesmerizing here, his narrative more straightforward, but it's the thinking behind The Unknown Terrorist that is depressingly obvious, even ham-fisted."

In an unprecedented move, book/daddy officially recants our position concerning the creation of the Bush Presidential Library at SMU: We are now for it. We were against it because, unlike just about every other commentator on the topic, including the happy Bush-boosters down at the Dallas Morning News' editorial offices, book/daddy will actually have to live near the damned thing. The certain-to-be blight-ish design (whatever it will be), the number of conservative think-tankers book/daddy will inevitably run into buying up all the lobster bisque at the foodstore while loudly defending Bush tax policies: For these reasons alone, book/daddy felt we must make a principled stand agin it. Even if we thought the bloody thing was going to get built anyway. Half a billion dollars, Dallas' Republican loyalty and SMU's hunger for any sort of national limelight is a combination hard to defeat.

But now book/daddy feels it is only right to accept our Change of Mind. We now support the Bush Presidential Library wholeheartedy.

Take heart, dear reader, let us explain. This monumental change came about only because of recent events. First, the voters of Highland Park agreed to sell to SMU a tiny strip of park land near the proposed site, the last parcel SMU needed for Total Domination of the Area. It's revealing to witness how much more foresight and planning and strong-arming-the-will-of-the-people has gone into this than, say, Bush's Iraq invasion. Conclusion: Next war, we let SMU fight it.

But this means that Highland Parkers, normally devout NIMBY folk, seem to have no idea what traffic and parking are going to be like with a presidential library and think thank-propaganda facility-memory hole being built on a residential street (Mockingbird) that frequently is so small it has no left turn lane.

So book/daddy figures The Idiots Deserve It.

Secondly, in light of the recent revelation that the Bush administration is such a twistedly secretive, guilt-ridden, cockamamie outfit that late one night, Alberto Gonzalez tried to get a drugged, hospitalized John Ashcroft to sign off on a surveillance program he'd already condemned as illegal, book/daddy feels any Bush presidential library will be a resource for professional historians and journalists for decades. It'll be a major make-work project for research clerks: uncovering what will certainly be ever more tales of scandal, law-breaking and incompetence.

And who says trickle-down economics don't work?

Here at BD HQ, we're painfully aware that, once again, we haven't fulfilled high expectations for posts this week. But we have not been idle. For one thing, we've been in Big Important Meetings. As if you care. And we have been sorting out plans for a royal visit to BookExpo, followed by a possible promenade down to D.C.

But we've also been doing battle for truth, justice and book review pages over at the letters section of Romenesko. Try here and then here.

Think of it as book/daddy on tour.

For more on Falling Man, Don DeLillo's remarkable -- but to my mind slightly unsatisfying -- 9/11 novel, here is Steven Poole's excellent review from the New Statesman and here is Adam Mars-Jones' equally sensitive but slightly more muted review from the Guardian. Mars-Jones has a superb description of what, for me, is the novel's problematic shape or organizing principle: "It's hard to tell whether this is a story of disintegration or its opposite, which isn't necessarily a problem; there are novels, for instance, JM Coetzee's Disgrace, that have made a perilous success of this tactic."

Needless to say, both review are more perceptive than Michiko Kakutani's grouchy dismissal in The New York Times.

One other aside: Reviewers have made much of DeLillo's remarkable invention, the performance artist Falling Man, who dangles from Manhattan buildings, in simulation of the tragically famous office workers who jumped to their deaths from the World Trade Center. No one seems to have noticed that in the '60s and '70s, American artist Ernest Trova made a well-known series of silkscreen prints and metal sculptures all with the same title, more or less -- "Study: Falling Man" -- and all featuring the same armless, modernistic humanoid figure, often standing but also often in a horizontal position, as if falling face down.

One other aside: Reviewers have made much of DeLillo's remarkable invention, the performance artist Falling Man, who dangles from Manhattan buildings, in simulation of the tragically famous office workers who jumped to their deaths from the World Trade Center. No one seems to have noticed that in the '60s and '70s, American artist Ernest Trova made a well-known series of silkscreen prints and metal sculptures all with the same title, more or less -- "Study: Falling Man" -- and all featuring the same armless, modernistic humanoid figure, often standing but also often in a horizontal position, as if falling face down.

I don't know whether Trova's works had any relevance for DeLillo (although one of the two times I've seen DeLillo, he was in an art gallery), but I thought I'd note the echo.

Josh Getlin writes in LA Times about how the recent quarrel between litbloggers and book reviewers over the decline of newspaper book pages is being resolved: We're all in the same, ever-expanding, if leaky, boat! The article manages to include Salon.com as a blog, when it's an online magazine, and never gets around to what would seem an essential point for professional writers:

Blogs, for the most part, don't pay. Book pages do, even if a pittance.

Over at Critical Mass, there's a round-up of panels about book reviewing at the upcoming BookExpo.

Bill Marvel's post to my 9/11 novel musings about the unexamined assumption that novelists today should deliver "topical musings" (see immediately below) has prompted this question: Can anyone think of a novel that came out immediately after an earthshaking event (say, within a year or two), and that novel remains a real literary achievement, something that changed or deepened our understanding of the event yet the book can also be appreciated without extensive knowledge of the relevant history?

I'm going to discount a number of WWI and WWII novels because those tragedies lasted so long that an author could have conceivably started writing a novel during the war that reflected on it, yet have plenty of time to layer the work so that, upon release, it would seem both immediate and the product of long, artistic gestation. Obviously, the event in question could be a disaster -- atom bomb, hurricane, flood, shooting -- but it could as likely be an invention, social upheaval, change in political administrations.

I'm asking because I'm curious about where this expectation, the media-pundit pressure came from: That after any cataclysm, novelists had better get busy pondering it to produce the definitive work that somehow manages to stand as a literary achievement yet be immediately newsworthy?

The first suggestion, posted in a comment to "9/11 as a novel: Why?", by Marion James is Suite Francaise by Irene Nemirovsky, which was begun as her diaries during the war and transformed into the first part of a longer novel even as she and her family were being rounded up.

An impressive choice. A tremendous Holocaust novel written even as the Holocaust began. Of course, the interesting factor with Suite Francaise is that its release was delayed by a half-century (which in itself made the book "newsy" for very different reasons), yet that "time capsule quality" made the novel feel so incredibly immediate and fresh.

Any other suggestions?

So just why do we expect our writers to produce the "Great 9/11 novel"?

Has there ever been a "great" Pearl Harbor novel -- the event most often compared to the Towers' collapse? From Here to Eternity is about all that one's memory can conjure up, and surely it doesn't qualify as great.

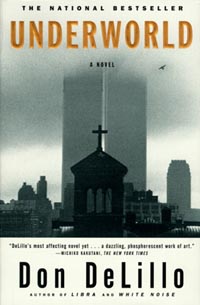

These thoughts struck me while reading Falling Man, Don DeLillo's astonishingly sharp yet ultimately unfocused new novel, as well as the reviews that have greeted it and the other attempts by novelists the past two years to come to grips with That Day. If ever an author has the literary chops to expound on those events, it would be DeLilllo -- considering all he's written about terrorism, assassination, disasters and the media. Indeed, the beautiful cover photo for Falling Man is an above-the-cloud shot looking down at the World Trade Center, eerily balancing the under-the-cloud photo that graces the cover of Underworld, looking up at one of the WTC towers. It's cut off by the fog, as if the book cover anticipated the building's billowing destruction a few years later.

But again -- Is there a "great" Stock Market Crash novel? Depression novels, yes. Word War II and Holocaust novels, of course. But we're talking about those singular, one-day catastrophes that change an era, re-direct history's course. Does anyone expect a great "Berlin Wall falling" or "Oklahoma City bombing" novel?

In part, it was the growing self-consciousness of American culture after World War II -- our assumption of world leadership in politics and the arts, our perceived need to advance our values against the Soviets -- that led to this peculiar and unexamined expectation: Novels would be a "wiser journalism," the novelist a kind of news anchor rushing to get out his take on events before his competitors do. We -- meaning, especially we journalists and critics -- now regularly anticipate major authors to weigh in on momentous occasions in a timely fashion, to pronounce, to explain why the events are, indeed, momentous.

In part, it was the growing self-consciousness of American culture after World War II -- our assumption of world leadership in politics and the arts, our perceived need to advance our values against the Soviets -- that led to this peculiar and unexamined expectation: Novels would be a "wiser journalism," the novelist a kind of news anchor rushing to get out his take on events before his competitors do. We -- meaning, especially we journalists and critics -- now regularly anticipate major authors to weigh in on momentous occasions in a timely fashion, to pronounce, to explain why the events are, indeed, momentous.

Of course, in Latin America and Europe, the novelist-as-engaged-political-commentator is a familiar figure. If journalism is "history in a hurry," then this makes the novel "journalism in an easy chair," journalism given time to think. "News that stays news" was Ezra Pound's reductive formula for art.

In America, the efforts of writers like Norman Mailer certainly played to this notion in a very late '60s-ish way: courting media and political prominence, trying to master the celebrity beast, to re-conceive the novelist's role as pugilist-pontificator. But it's a way of reaching the American public that seems to have passed. There seems to be no major novelist who matters to American readers anymore -- at any rate, not on that event-defining, consciousness-shaping level. The Executioner's Song, Mailer's last achievement in his journalist-as-sage mode, was 28 years ago -- a generation past.

Stephen Colbert attacks the "book critic literazis" and has a good time with Salman Rushdie (scroll down to the video about the decline in newspaper book review pages).

... has been roving East Dallas, reportedly killing as many as 25 cats.

Last night, they killed our two younger cats. We didn't hear the dogs because of a rampaging electrical storm. Found the bodies this morning. The youngest cat was less than a year old.

Hell of a way to start a day. Something similar happened almost 10 years ago, and we thought the situation had changed. You can read my column from that time on the jump.

Transplanted American-Britisher-American Bill Bryson has been named president of the Council for the Protection of Rural England, an 80-year-old rural conservation group that was once "about admiring fluffy lambkins gambolling on the greensward" but is now "deeply involved in intensely political issues, including urban sprawl, affordable rural housing, pressure on green belts, noise and light pollution, and the loss of village post offices, pubs and shops."

Mr. Bryson, who grew up in Iowa, lived in England for 20 years, wrote about his irritated love for the place in Notes from a Small Island, and once, in an interview, described England as "crazy as fuck, but adorable to the tiniest degree" -- which could stand as a decent estimation of most of Mr. Bryson's books, as well, if "crazy" were replaced by "amusingly, crankily sane."

The very discouraging news here at B/D HQ (book/daddy headquarters) is that a local media job that book/daddy had been angling for for several months -- a job that seemed practically created for him, a job that isn't likely to come along again in the Dallas area -- went to someone else.

Alas. Back to the drawing board.

The good news is that book/daddy's daughter, the Comic Book Queen, won a contest at her arts magnet high school, the Booker T. Washington School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Her painting will now hang in a Dallas courthouse and she has received $500. The winning image is a close-up portrait of blind justice with a scroll coming out of her mouth containing the Latin motto, "Fiat justitia, et pereat mundus."

The phrase has been most commonly translated as "Let justice be done lest the world perish." Or "Let justice reign even though the world perish." There is the related line, "Let justice be done should the sky fall (Fiat justitia ruat caelum)" -- attributed to Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus (died in 43 BCE.) The general meaning is that reasons of state (or other powerful interests) must not sway the course of justice, no matter the consequences. Or justice must prevail lest the (human) world cease to be truly human.

The truly interesting thing is trying to track down the motto's origin. Many people cite Hegel in 1821. Karl Marx quoted the line approvingly. The Anglican clergyman and author Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667) attributed a version of it to St. Augustine. By the time it first appears in English literature in the early 1600s, it was already considered a commonplace-- no need to give an author.

The most common origin is the personal motto of Ferdinand I. Don't know him? We didn't either. While trying to track him down, the Comic Book Queen and book/daddy came upon Ferdinand I of Austria, who was a feeble-minded nut case propped up on the throne by Metternich. For a brief moment, the Queen had the happy thought that she had actually gotten a Dallas courthouse to post a quotation from a king whose most famous command -- when told by his cook that peach dumplings were out of season -- was "Ich bin der Kaiser und will Knodel!"

"I am the emperor and I want dumplings!"

Alas for such a bit of courthouse dadaism, the appropriate Ferdinand I is actually Ferdinand I of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperor, younger brother of the better known Charles V and, in general, a punching bag for Suleiman the Magnificent and his Ottoman invasion of Hungary. He was also on the losing side, ultimately, of the Counter-Reformation in trying to suppress German Protestantism, though he did win a victory or two, establishing the archdiocese of Prague and inviting the Jesuits into Prague and Vienna.

Where he got such a rousing Latin tag line for his personal motto is not clear. book/daddy doesn't believe for a second that Ferdie came up with it on his own.

Bob Mong, editor of The Dallas Morning News, responds to questions over at Critical Mass about books coverage in the paper and book/daddy's departure from same. I'll let his comments stand; any response I make would probably appear bitter or obsessive.

Yep. book/daddy's all about looking forward these days...

... if book/daddy still have any readers left at all. Official apologies again for the lackluster contributions the past week or so. The bronchitis has left Book/Daddy Headquarters seriously understaffed.

Well, the bronchitis, plus the ample supply of codeine. And the wretched weather. It's currently flooding in Dallas, if you haven't heard.

All of which is why whenever someone at Book/Daddy HQ suggests just giving up and going back to bed, the motion always seems to pass unanimously.

You can listen to National Book Critics Circle president John Freeman on National Public Radio's "Talk of the Nation"