book/daddy: November 2007 Archives

... book/daddy is off to visit book/parents. I'll check in, but the postings will be getting even weaker than usual.

In light of the latest National Endowment for the Arts' study about Americans' declining reading habits, The New York Times ran a story Sunday about the mystery of why people read. It featured the predictable anecdotes about how a particular book encountered while young and ignorant turned on such authors as Sherman Alexie and Junot Diaz. Although interesting in that regard, the Mokoto Rich story shed little light on the process of becoming a regular reader -- only confirming the feeling of helplessness or frustration the NEA data imparts.

In light of the latest National Endowment for the Arts' study about Americans' declining reading habits, The New York Times ran a story Sunday about the mystery of why people read. It featured the predictable anecdotes about how a particular book encountered while young and ignorant turned on such authors as Sherman Alexie and Junot Diaz. Although interesting in that regard, the Mokoto Rich story shed little light on the process of becoming a regular reader -- only confirming the feeling of helplessness or frustration the NEA data imparts.

There is always going to be something serendipitous about the link-up between the right book and the person who will appreciate it. What should be asked is not how young readers get started but how do they stay readers, how do they become habitual readers? This, after all, is the focus of the NEA study: A decline in "recreational reading" reportedly has led to a decline in reading and writing skills.

Yet -- pleasant surprise -- we actually know a few things about how the reading habit starts. And how it might be encouraged.

Pat Barker, Frankenstein, Cass Sunstein on the internet, Samuel Johnson, Thrillers, Denis Johnson, Alan Furst, Caryl Phillips, Richard Flanagan, George Saunders, Michael Harvey, Larry McMurtry, Harry Potter and more ...

At last year's Texas Book Festival, book/daddy had a delightful time with Colm Toibin, the Irish writer, author of the brilliant novel, The Master. At the time, I wondered what he might make of his visit to Texas -- he was teaching at the Michener Center at UT.

Soon we'll find out. He has a short story about an Irish writer in Texas in Zadie Smith's new anthology, The Book of Other People (set for release in the US in January). David Mattin has a review in The Independent and cites Toibin's story as the best in the collection.

On the other hand, Stephen Abell in his review in the TLS doesn't even mention the story.

John Hodgman, via Dwight Garner's fine blog, Paper Cuts.

Hobo Matters, an American Experience video:

... Thanksgiving is upon us, and the holiday turkeys, like the one pictured, have arrived.

... Thanksgiving is upon us, and the holiday turkeys, like the one pictured, have arrived.

You'll also have noticed that book/daddy's blogging has declined somewhat. It will decline further because I'm going to visit my parents next week. Soooo, for the next week and a half or so -- maybe longer given all of the cheerful predictions about America's crackerjack air travel system -- postings will be light. And book/daddy's readership will probably decline into the negative digits.

Other than that -- Happy Thanksgiving! Have some turkey, although I would not recommend the one pictured here. And may whatever professional athletic team you are rooting for tomorrow -- the one with the brightly colored outfits, the exuberant dance moves in the endzone, the ongoing scandals and the billionaire owner who screwed your town to get his stadium built -- whoever they are, may they be victorious. Or at least, not more embarrassing than they already are.

The Book Design Review has made its selection of the best book covers of 2007. You can even vote on the one you like.

For what it's worth, here are some of my favorites of the year.

One reason I quit grad school more than 20 years ago at the University of Texas at Austin was the sweatshop exploitation of temps -- adjuncts, "pool people," part-timers, non-tenure track teachers. At the time, the academic job market had tanked, and it seriously looked as though that's where I'd wind up, too, with my eventual Ph.D --teaching remedial English in some non-tenure track position, even on a part-time, no-benefits basis.

Fast foward to last year: I leave The Dallas Morning News and in the back of my head, I think: If worse comes to worst, I can always teach. I have backgrounds in journalism, literature and drama; I could go with any of those three areas. Plus, I know chairmen of departments. Heck, I even know deans.

Then my professor-dean-department head friends start telling me the grim news. They've had hiring freezes for years, or if they're at least hiring people, they're hiring only adjuncts, and at wages that should shame them. They have no choice. $2000 per class or less -- imagine teaching five classes, a murderous schedule, grading hundreds of papers or tests week after week, and still making less than $15,000 with no medical benefits. I have a relative who's an award-winning, book-published professor. He hasn't been able to get a full-time teaching job commensurate with his experience and achievement for five years.

In short, for all of the screaming and gloating about the death of mainstream media, academia is actually in worse shape -- and there's barely a peep. I tried to get some journalist-contacts interested in this, even a couple who write about education. Shrugs.

So now it's a front page story in the New York Times. The estimate is that 70 percent of teaching positions at colleges and universities are now filled by adjuncts and temps. The article is decent, although it doesn't convey a fraction of the frustration and bitterness of the exploited, the trickle-down effect on students.

It also doesn't even address what would seem a key question: Why are parents paying full-load tuition for their little darlings to go to college -- tuitions that have skyrocketed in recent years when, as in Texas, they were "deregulated" in another fine example of free-market thinking -- yet their children are being taught primarily by temps?

Over at Quick Study and Infinite Thought and Crooked Timber, we've all been having a nifty, rambling and remarkably learned conversation about the aesthetics, taxonomy and narrative imperatives of porn. Join in, as they say at swingers' parties, and check out the Nude Maypole Snail Dance or whatever that Lewis Carroll-with-the-lid-off photo is at Infinite Thought.

Not that book/daddy would know anything about all that stuff. But as Scott McLemee has discovered once again, it is a great way to boost reader hits for your website. If you haven't already, see book/daddy on how Instant Post-Structuralist Erection can improve your love life and your website readership.

In fact, amid all of that cross-pollination, one poster claims to have found what may be the ultimate bit of web bait. This is depressing: It's the term, "Japanese schoolgirls."

The death of Norman Mailer leads John Walsh in the Independent to consider the demise of the Great American Novel. Or at least, the pursuit of same by American novelists. Perhaps that species of fiction is extinct, the hunters having defoliated everything else in the immediate eco-system.

One can over-sentimentalise the idea of the novelist as passionate adventurer, whose prose is inspired or sharpened by some dark experience (such as war.) It's mostly a foolish dream. But one can feel a lowering of the spirits when confronted by the spectacle of the descendants of Bellow and Roth, Updike and Mailer - the creative-department students whose impulse to write derives mostly from feeding off other books, who would rather fashion a short story, good though it may be, rather than attempt a balls-out epic novel. "The originators, the exuberant men, are gone," wrote Evelyn Waugh about the English novel in The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, "and in their place subsists and modestly flourishes, a generation notable for elegance and variety of contrivance." The older generation of great American scribes, the exuberant men and women, are going at alarming speed; and with them goes the dream of the Great American Novel that focused and energised them all.

A typical oversight from Mr. Walsh's history of GAN candidates: Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. Mr. Walsh, interestingly enough, also brings in the fallout (and literary fizzles) from 9/11. In fact, one could make the related argument -- as book/daddy did with the "Great 9/11 Novel" -- that "in part, it was the growing self-consciousness of American culture and American authors after World War II -- our assumption of world leadership in politics and the arts, the perceived need to explain and advance our values against the Soviets' -- that led to this peculiar and unexamined expectation, especially on the part of critics, that novels are a kind of 'wiser journalism.' We now regularly anticipate that major authors, like competing news networks, will eventually weigh in on significant events, to extrapolate, to pronounce, to tell us why they're significant."

After all, it's only after World War II -- with the boom in academic culture from the GI Bill -- that novels like Moby-Dick even began to be considered as possible "Great American Novels" at all. While Mr. Walsh (along with fellow Brit crit, James Wood) attempts to pin literary self-consciousness as a weakness on the generations after Mailer's, it was the "Greatest Generation" that first went after the Great White Whale armed with a pen and a library.

Excellent, reflective essay by novelist John Banville on pulp crime fiction at Bookforum.

"Crime fiction flourishes in hard times. The fiction reflects the times, and the times color the fiction. There is a rawness in the pulp stories, even those by "literary" writers such as Chandler and Hammett, that is not due entirely to the exigencies of the marketplace. At their best, and even, perhaps, at their worst, these yarns express something of the unforgiving harshness and dauntless optimism of life in America in the decades between the wars."

"Crime fiction flourishes in hard times. The fiction reflects the times, and the times color the fiction. There is a rawness in the pulp stories, even those by "literary" writers such as Chandler and Hammett, that is not due entirely to the exigencies of the marketplace. At their best, and even, perhaps, at their worst, these yarns express something of the unforgiving harshness and dauntless optimism of life in America in the decades between the wars."

Perpetua sat on the couch in her new apartment smoking dope with a handsome bassoon player. A few cats walked around.-- from "Perpetua," by Donald Barthelme, included in the new collection, Flying to America: 45 More Stories"Our art contributes nothing to the revolution," the bassoon player said. "We cosmeticize reality."

"We are trustees of Form," Perpetua said.

"it is hard to make the revolution with a bassoon," the bassoon player said.

"Sabotage?" Perpetua suggested.

"Sabotage would get me fired," her companion replied. "The sabotage would be confused with ineptness anyway."

In 1965, Ishiro Honda, the Japanese director behind Godzilla, released a fairly dreadful film -- to my mind, at least. Japanese monster aficionados, on the other hand, seriously enjoy man-in-a-rubber-suit movies. In any event, in America, his fairly dreadful film was given a title that was shamelessy overblown but was -- we can all agree -- a grabber:

In 1965, Ishiro Honda, the Japanese director behind Godzilla, released a fairly dreadful film -- to my mind, at least. Japanese monster aficionados, on the other hand, seriously enjoy man-in-a-rubber-suit movies. In any event, in America, his fairly dreadful film was given a title that was shamelessy overblown but was -- we can all agree -- a grabber:

Frankenstein Conquers the World

Susan Tyler Hitchcock could have borrowed the title for her new book, Frankenstein: A Cultural History, because that's the argument she makes: What was considered a disreputable little novel -- even a blasphemous one -- went on to shape our responses to science, genetics and female Romantic authors. It has entered the literary canon as well as the pop-culture universe as a 19th-century classic.

When Mary Godwin wrote Frankenstein in 1816, she was only 18 years old, a daughter of radical parents, and an unwed mother who'd run away with her married lover (later her husband), Percy Bysshe Shelley. She wrote a gothic novel unlike any other -- no haunted castles, no beautiful sirens trapped alive in crypts, no ancient family curses. There is nothing essentially "supernatural" in the story. Instead, Frankenstein is the tale of a man inventing another man; it's a "'scientific" creation story, Genesis with electric sparks. Coming as it did at the start of the Industrial Revolution and inspired, in part, by new galvanic experiments, Mary Godwin's novel became over the years a symbol of technology run amok. This is ironic, considering that in Godwin's age, there was relatively little modern technology that could even run amok: no gas engines or electric dynamos, and the first steam locomotive wouldn't run on tracks for another 14 years. Even so, as a creepy yarn about science (if vague on the technical details), Frankenstein has been called our first truly modern myth.

Yet as Ms. Hitchcock shows, our knowledge of that myth is mostly drawn from the still-powerful Boris Karloff films of the '30s -- and those Frankensteins have little to do with the novel.

book/daddy's posting have been paltry this week because I had two deadlines and, much more importantly, last night was the gallery opening of my daughter'ssenior exhibition (she attends the local arts magnet in visual arts). Food and drink preparations. Decor. Hauling stuff. Clean-up.

book/daddy's posting have been paltry this week because I had two deadlines and, much more importantly, last night was the gallery opening of my daughter'ssenior exhibition (she attends the local arts magnet in visual arts). Food and drink preparations. Decor. Hauling stuff. Clean-up.

And parental hangover this morning.

In his weekly sermon berating us for failing (once again!) to meet his high moral and civic standards, Dallas Morning News opinion columnist Rod Dreher quotes me a number of times without, of course, actually identifying me.

The passages were from a 2005 feature on why Dallas doesn't have a native intellectual class, and specifically a chief reason I advanced for this lack: It's one of the effects on area culture and society of our wicked "churn." Research has shown that Dallas has an extremely high percentage of residents who are brand-new and won't stay long. We're here for the jobs and then we're gone -- that's churn. It's very difficult, book/daddy concluded, to maintain any sort of collective effort. Neighborhood groups, brainy networks, social outlets, even political campaigns can't muster up regular support. (The other chief reason for a dearth of brainy sorts is a lack of relevant jobs -- there are few policy journals, think tanks, institutes and even a serious graduate research library in these parts.)

In this context, Monsignor Dreher quotes me as writing "it's hard to establish traditional social networks with such a mobile population." Actually, I never wrote that -- the monsignor added the word "traditional." My adjective was "citywide" and the examples I used were arts groups and professional associations. Probably not, one suspects, the conservative monsignor's notions of "traditional."

More importantly, Msgr. Dreher uses this info as a way to chastise readers for our lousy voter turnout last weekend (in reality, it was low but higher than expected). His real purpose, though, is to blast a lawsuit by Hispanic activists in Irving, Texas (a suburb of Dallas), demanding a court-imposed system of single-member districts as a way to ensure better minority representation. Funnily enough, such a lawsuit -- even though the monsignor says this one shouldn't win and won't win -- is exactly what happened in Dallas a generation ago. To the consternation of the News and to establishment whites in general at the time, the federal courts forced Dallas to develop its current single-member set-up because of a history of calculated racial exclusion.

One does wonder where those Hispanic activists get their wild-eyed ideas. Silly buggers. Of course, after two terms of the Bush administration stuffing Justice Department positions and federal judgeships with people dedicated not to enforcing discrimination laws, perhaps the monsignor is right in his prediction.

But that's not why Msgr. Dreher thinks the lawsuit will fail -- no surprise there. The lack of HIspanic representation in Irving is not due to an unfair system, he argues. It's actually because of laziness and indifference among Hispanic voters, and he cites voter turnout and population figures to prove it. Apparently -- if we are to follow the monsignor's argument here bringing in my point about churn there at the beginning -- apparently, Hispanics, who have a much larger percentage of adults without a high school diploma, are coming here for those big-buck, high-tech, leaf blower jobs but then they're moving on to greener pastures when they get promoted to senior office manager. There's a lot of churn and advancement in the yard maintenance, housecleaning and no-skill construction areas.

If Msgr. Dreher hadn't been so quick to hurt himself, patting himself on the back for voting last Saturday even though, he confesses, he really didn't care much about the outcome, he might have delved a little further into some of the research on voter turnout, especially among the working-class, the poor and minorities. Their turnout record is a fine example of his fellow conservatives' pride and joy: the self-interest of the marketplace.

Basically, why should they vote? There's very little advantage for them: Very little changes or has changed in their favor. Health care, affordable housing, the well-established prejudice in housing loans against them (and owning a home automatically would elevate them into middle-class tax breaks but they can forget those), the lack of mass transit that requires them to own a car (and car insurance), the inability of minimum wage increases to make a dent on their poverty level even when working two jobs: These problems haven't really changed in decades. And the widespread perception -- surely it's only a perception -- that government policies skew toward benefiting the wealthy and well-connected, this just might increase their sense of alienatioin. The argument, made by these guys, for one, is that positive party contacts with folks across socioeconomic levels help demonstrate the effectiveness of voter participation. And as politicians have decided to hell with that, we need to court the rich donors, such positive, grass-roots contacts have plummeted. And so has voter turnout.

Or then again, it could be just those Mexicans, being lazy and indifferent again.

David Brooks certainly sounded reasonable in trying to contextualize Ronald Reagan's infamous "states' rights" speech in 1980. The speech wasn't about race relations, post-convention Republicans had actually been trying to court black votes, no one interpreted the short speech at the time in the way demonizing liberals have since cast it except for a couple of newspapers. Calling Reagan personally racist or a panderer to bigots is a slur, Mr. Books' contends.

But now a pissed-off Phil Nugent has taken Mr. Brooks' argument apart.

... Michiko Kakutani has the best take on Norman Mailer's writing. It's the nonfiction journalism that's best, notably Executioner's Song, Miami and the Siege of Chicago, The Fight and The Armies of the Night. As occasionally demented and self-indulgent as these are, they still often are sharp, smart and courageous in their admissions. Many of the novels, on the other hand, took the demented into the downright embarrassing, notably An American Dream and Ancient Evenings.

There is also Louis Menand's elegant appreciation at the New Yorker.

And then, there's always Roger Kimball who managed, in less than 24 hours, to write more than 5,000 chilly words detailing at length everything he ever hated about Mr. Mailer, his books, his prose, his politics, his friends, his causes, his crimes, his campaigns, his critics.

I think it was Mr. Mailer who once observed that you gotta respect an overpowering hatred like that. The tigers of wrath being wiser than the horses of instruction, and all that. Amid the tirade, one begins to feel a certain affection for Mr. Mailer, for all his ridiculous faults, just because he could infuriate someone like Mr. Kimball this deeply.

It took me months to start this graphic novel because Bryan Talbot's visual design is off-putting to the point of headache ugliness: a color-drenched overload of photos, news clippings, Tenniel prints and dozens of different drawing styles. Muscle your way past that, though, and Alice in Sunderland is truly a wonderland. It's Talbot's attempt to relocate Lewis Carroll's inspiration from Oxford to his life in the seaport coaltown of Sunderland. Just like its visual style, the book is self-indulgent, long-winded, the attic-emptying obsessions of a crank historian and town booster. But like its Carrollian inspiration, it's also whimsically

The ancient Greeks were actually pretty conflicted about homosexual sex. And as James Davidson, author of The Greeks and Greek Love (due Nov. 29), argues, ancient Greek scholars have been pretty screwed up about it, too:

"Sometimes the Greeks seemed to approve of it wholeheartedly, even to suggest that it was the highest and noblest form of love. And other times they seemed to condemn it. Sometimes the ideal seems to be a spiritual, passionate but unconsummated 'Platonic' love, like that much praised by Plato's Socrates. It was this notion that allowed Ganymede, ancient mascot for the vice unmentionable among Christians, to appear on the doors of St Peter's in Rome, where, amazingly, he remains ...

"So how do we begin to make sense of this truly extraordinary historical phenomenon, an entire culture turning noisily and spectacularly gay for hundreds of years? When I first embarked on the research for my book The Greeks and Greek Love I was not expecting any easy answers, but I did not expect it would be quite as hard as it turned out to be, and take so long as it ultimately did."

"The hippies were utopian, deluded, egomaniacs - and fundamentally very stupid. Think Neil from The Young Ones. They had this infantile delusion, which still permeates our society, that when bad things happen it is a sign that the order of the world is somehow disharmonious, and that as a remedy - in that most hideous Blairite mantra - 'something must be done'."

"The hippies were utopian, deluded, egomaniacs - and fundamentally very stupid. Think Neil from The Young Ones. They had this infantile delusion, which still permeates our society, that when bad things happen it is a sign that the order of the world is somehow disharmonious, and that as a remedy - in that most hideous Blairite mantra - 'something must be done'."

book/daddy suffers very little from boomer nostalgia. Hence, this blog will not be one to defend the excesses of hippies (or of Heather Mills, for that matter -- the actual target of Patrick West's spleen: She's the estranged wife of a Beatle, so there's the justfication for that logical long jump). But insofar as the above is part of a generic, conservative rant against all things '60s, book/daddy will merely cite this NYTimes article on the Plastic People of the Universe, the hippie rock band whose banning led to Charter 77 and the Velvet Revolution that overthrew Soviet rule in Czechoslovakia (the subject of Tom Stoppard's new Broadway play, Rock 'n' Roll) as well as this review of Matthew Collin's The Time of the Rebels: Youth Resistance Movements and 21st Century Revolutions. It examines how Otpor ("Resistance"), among other groups, fueled opposition to Eastern European/former Soviet dictators, using tactics inspired by the likes of John Lennon and rather '60s-sounding, New Left thinking.

As reviewer Daniel Trilling notes, the "music revolutions" have tended to spawn a great deal of wish-fulfillment mythology that ignores larger economic and global-political forces. Still, they did have a real effect ("something must be done"). Besides, as a political platform, "no more war, an open democratic system and a good band" sounds far healthier than "compassionate conservatism" has proved. And ya gotta love the incarcerated barrel:

"Music, in particular, became an ideological battleground. In Serbia, folk music was used by Milosevic and his supporters to promote their narrow-minded, racist take on national identity. By contrast, Otpor soundtracked their rallies with western-style rock, a rebellious move in a country that had only recently been bombed by NATO. As one activist, Gavrilo Petrovic, tells Collin: 'People in Otpor wanted Slobo out, sure. They wanted no more wars, no more death, an open state and a democratic system. But that also involves wanting to have a good band coming to play here and not having to be ashamed of this country ...'

"Otpor members in Belgrade, for example, charged passers-by money to hit a barrel that had Milosevic's face printed on the side. Stunts of this sort allowed people to publicly express their anger at a government that had dragged them into years of bloody conflict during the break-up of Yugoslavia, while simultaneously mocking its authoritarian tendencies. In this instance, the crowd fled as soon as the police arrived, leaving them with no option but to arrest the barrel."

Beginning yesterday, Friday, Nov. 9, book/daddy will be cross-posting some of his items on the new arts & culture blog at KERA, the NPR/PBS station for Dallas-Fort Worth. I'm the station's new "critic-at-large," a title that, yes, often makes me consider a new diet. If you're interested, what I'll be posting over there and likely not here are area theater reviews.

Thank you. We will now return to our regular programming.

The Elegant Variation has the intermittently hilarious, translated transcript.

A provocative title, even a misleading one, but it got your interest. So:

A commonplace causal connection made by many bloggers has been the decline (and, of course, predicted demise) of mainstream print media because of the rise of blogs. Specifically, book blogs exist (and are booming) and their coming supremacy come at the expense of the dying Sunday book pages in newspapers.

This has been an abiding assumption -- if not an excited anticipation -- behind many arguments about diminished print coverage of books. We bloggers are the outsider-independents and underdog-alternatives who, at last, have begun to overturn the hegemony of the Mainstream Media Book Reviewers.

I've provisionally responded to this argument with the rock-solid declaration, um, maybe, gee, I don't think so, or at least perhaps not yet. But since then, I've decided that "Blogs Triumph Over Print Reviews" is a basic misreading of what has been happening.

To be clear: The decline of book pages has not been caused by the rise of book blogs. Not one bit. On the other hand, a case can certainly be made for the reverse. That is, the cutbacks (or more accurately, the long-term failures and middle-brow limitations) in newsprint books coverage have certainly helped inspire some book bloggers. As Jessa Crispin of Bookslut said during the panel on literary criticism that book/daddy moderated at the Texas Book Fesival in Austin over the weekend, the major review outlets keep reviewing all of the same authors, and few of the kinds of books and authors she likes were getting attention, so she started writing about them on her website.

But again, the claim that, subsequently, because hordes of people like Ms. Crispin or Mark Savras or even -- blush -- book/daddy went to their computers and blogged away, the Sunday book pages and magazine book reviews have all started to gasp for air, such a claim is groundless.

What first bothered me about this claim is that it's more or less derived from a leftist critique of conservative corporate-media hegemony. Mainstream book reviewers chase after those authors whom publishers deem important, while publishers push those authors who find reviewers' favor, and everyone is rewarded (prestige, sales, promotions) in a kind of closed-circuit, corporate-cultural circle jerk.

Yet the same claim is being made, more or less, by right-wing politcal blogs about liberal media hegemony.

The old expression for excusing a momentary slip-up is "Even Homer nods ... " Perhaps we can coin a new one for the embarrassing silence that occurs when you're asked a perfectly general question about a book you just read and even reviewed and now can't remember a thing about: Even Scott McLemee forgets ...

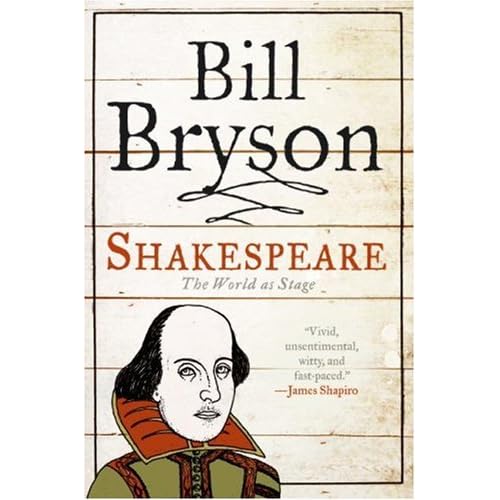

Shakespeare: The World as Stage, by Bill Bryson

Shakespeare: The World as Stage, by Bill Bryson

Not enough Bill Bryson and not enough Bill Shakespeare. The World as Stage is the latest in the Eminent Lives series of brief bios. Nobody may need yet another book on Shakespeare, Mr. Bryson admits, but "this series does."

So here he is: Mr. Bryson constrains himself to relating the few known facts in a conventional chronological narrative, repeatedly emphasizing just how little we do know for certain (all three supposed portraits of Shakespeare are relatively dicey in their provenance, for example). He digresses into interesting byways (Christopher Marlowe) and period color (the plague) as well as the occasional foray into journalism (a visit to the National Archives). One wishes for more of the latter, much more: Mr. Bryson's characteristic humor and wry observations would have bumped up the proceedings enjoyably. After all, he gets top billing over the Bard; he should have let himself expand things.

Given all the wish-fulfillment fiction about the Bard, sticking to just the facts, ma'am, is certainly admirable. But equally dismissing all suppositions and theories is both a flawed and cramped argument.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A New Verse Translation, by Simon Armitage

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A New Verse Translation, by Simon Armitage

From the suit of medieval armor on the bold black book jacket and the prominent blurb from Seamus Heaney, it's plain that publishers Faber & Faber (in the UK) and W.W. Norton (in the US) and poet Simon Armitage are aiming for a popular hit in the mold of Mr. Heaney's brilliant (and surprise) bestseller, Beowulf. (Mr. Armitage, in fact, thanks Mr. Heaney for his enthusiasm and support).

book/daddy doesn't think the big sales are going to happen. First, needlesss to say, the poems are very different. Gawain is a much more courtly work. Yes, Beowulf was almost certainly written for a noble audience and read before a lordly dinner party, but the nearly 600-year distance between the two counts for something. The Beowulf poet may admire the metal work on a sword or hail a well-built mead hall, but he has little to compare to the pages that the Gawain author devotes to fingering the embroidery, bedding, flowing silk robes, room decor, delicate silver spoons and then savoring the well-spiced servings of soup, fish and bread.

Second, Beowulf himself is basically an action hero -- the new Robert Zemeckis film, which by the way, judging solely from its trailer, looks absolutely horrrible -- is only the latest "sword and muscle" adaptation going back several decades. In typical Schwarzenegger fashion, for example, when the chips are down, Beowulf just rips off Grendel's arm bare-handed.

A fairly unnerving prospect, yes? Considering the number of unhappy, unsavory, twisted, driven, needy sorts of people who populate a typical Philip Roth story.

This past weekend, book/daddy moderated a panel on literary criticism at the Texas Book Festival in Austin (more about which, later). One member of the panel was Steven Kellman, UT-San Antonio English prof, prolific author of literary studies (Loving Reading: Erotics of the Text) and the recent Nona Balakian winner, the top prize given by the National Book Critics Circle to a book reviewer. In subsequent discussions with him, he mentioned something I'd not been aware of -- which many readers are unaware of.

In Roth's latest novel, Exit Ghost, the author returns not only to his infamous alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, but a number of other characters, including the late E. I. Lonoff, a short story writer whom Zuckerman knew and admired. It's fairly well known by now that the model for Lonoff is not Bernard Malamud, as some originally surmised, but Henry Roth, author of the classic 1934 novel, Call It Sleep. It's in Exit Ghost that the Henry Roth model is made plain: Zuckerman is pestered and infuriated by a would-be biographer of Lonoff, and sets out to quash the biographer's project because it advances the theory that Lonoff suffered a huge case of writer's block over guilt about his incestuous relationship with his sister.

I didn't make the following connection because, frankly, I've not enjoyed the recent Zuckerman novels much, so I didn't get far into Exit Ghost before moving on to other books. But the name of the thoroughly obnoxious biographer in the novel is Kliman -- and Steven Kellman is the biographer of Henry Roth. It was Steven who argued -- in Redemption: The Life of Henry Roth -- that shame over being expelled from high school for theft and a long adolescent incestuous relationship with his sister caused Roth to forego major works of autobiographical fiction after Call It Sleep.

A slight, cheeful fellow, Steven is hardly the ominous, 200-lb, 6-ft three Kliman who bedevils Zuckerman, but otherwise, it's hard not to see, well, the resemblances. Steven writes about those surprising resemblances for the Jewish book site, Jbooks.com here.