book/daddy: January 2007 Archives

There's a nifty, gimmicky upside to Google's mass digitalization of books, whether one finds that prospect ominous (Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge) or not. Google Book Search will permit readers to map out locations mentioned in a particular volume. While reading a book, you just activate this feature and you get an interactive Google Map with the little pushpins stuck in it and all the addresses listed, plus relevant lines from the text in question. It's a way, software engineer David Petrou says, to "activate the static information" in a book.

Or hey, maybe publishers could just start coming out with, you know, maps printed in the front of books. All of the Alan Furst thrillers I've been reading lately have maps of Hungary and Roumania. An idea like that could catch on.

Or maybe not. Go to the jump to read my column about the need for maps in books.

... for the National Book Critics Circle nominations. It only looks easy. It isn't.

... but this San Francisco Chronicle story puts the collapse of Advanced Marketing Services and -- more importantly -- of Publishers Group West in the clearest, direst terms:

"More than 130 independent publishers across the country were hurled into financial crisis on Dec. 29 with the bankruptcy of the parent company of Publishers Group West, the Berkeley firm that distributes books from much of the small press world....

The bankruptcy threatens the survival of many of these small presses. This week, a potential white knight appeared in the form of Perseus Books Group, a New York company that is offering to pay the book publishers 70 cents on every dollar they are owed. But the bailout is far from certain.

The bankruptcy rocked a part of the literary world that even the most avid readers don't pay much attention to -- the system that enables small presses to get their wares onto the shelves of bookstores and, eventually, into the hands of consumers."

Dorothy Samuels in the New York Times has offered a very intelligent compromise for SMU on the issue of its accepting the somewhat tainted Bush presidential library. She proposes SMU accept the library but only on two conditions. First, the Bush administration rescinds Executive Order 13233, which cuts off a lot of scholarly access to presidential papers, and second, that the Bush administration reveals the names of the library's influence-buying donors (which may eventually happen with legislation being proposed by Nancy Pelosi, but who knows?).

Unfortunately, both of these issues -- paranoid secrecy and the influence of big money on politics -- cut to the heart of much of the Bush administration's thinking and methodology. So I'm willing to bet that the Bushes won't budge on either point. Recall the recent supposedly conciliatory State of the Union address by the president, followed immediately by the vice president's typically sparkling appearance on CNN, in which he declared that, unequivocally, je ne regret rien and screw you, Wolf Blitzer.

Also, alas, for those of us on the ground, as it were, the proposed solution won't address the large-elephant-footprint effects of the new library on the neighborhood (see below).

Still, Ms. Samuels' argument gets us away from -- on the one side -- the oppose-it-at-all-costs opponents who mostly seek a referundum on the administration's misdeeds and, on the other, the boosterish cheers coming from The Dallas Morning News' editorial board and op-ed page, which claim, in all seriousness, that the new library will make Dallas blossom into an intellectual's paradise.

I told you before: Stop laughing.

A number of years ago I wrote what was the latest in a depressing series of features about declining numbers among independent bookstores -- you know, the usual handwringing, the fall of the little guy, kids losing all interest in print-related objects, the drop in ABA membership from more than 4,000 to fewer than 2,000 -- when I learned that actually, we've always lost bookstores at a depressing rate.

What we haven't been getting is replacements, people who want to own or run such a thin-profit-margin endeavor.

Now, all of a sudden, there's been a notable uptick in new bookstores, says Teresa Mendez in the Christian Science Monitor.

This is one of the things that makes Alan Furst such a remarkable writer of historical thrillers. His specialty is wartime or pre-war Europe, and this is from Blood of Victory:

Belgrade -- or so the British cartographers called it. To the local residents, it was Beograd, the White City, the capital of Serbia, as it had always been, and not a place called Yugoslavia, a country which, in 1918, some diplomats made up for them to live in. Still, when that was done, the Serbs were in no shape to object. They'd lost a million and a half people, siding with Britain and France in the Great War, and the Austro-Hungarian army had looted the city. Real, old-fashioned looting -- none of this prissy filching of the national art and gold. They took everything. Everything that wasn't hidden and much that was. Local residents were seen in the street wearing curtains, and carpets. And ten years later, some of them, going up to see friends in Budapest, were served dinner on their own plates.

Belgrade -- or so the British cartographers called it. To the local residents, it was Beograd, the White City, the capital of Serbia, as it had always been, and not a place called Yugoslavia, a country which, in 1918, some diplomats made up for them to live in. Still, when that was done, the Serbs were in no shape to object. They'd lost a million and a half people, siding with Britain and France in the Great War, and the Austro-Hungarian army had looted the city. Real, old-fashioned looting -- none of this prissy filching of the national art and gold. They took everything. Everything that wasn't hidden and much that was. Local residents were seen in the street wearing curtains, and carpets. And ten years later, some of them, going up to see friends in Budapest, were served dinner on their own plates.

Admittedly, Blood of Victory shifts

locations a lot -

But Furst does it so smoothly and enjoyably. He treats the reader well. As much as the story or the characters, he seems to say, this is what a historical thriller is about, this kind of texture. It's not just data nor is it a bit of war-is-hell, tough-guy posturing on the narrator's part. It's evocative, graceful, even humane in the way the author, in that last line, clearly understands the anger and surprise of the Serbs while also relishing the humor of the situation, appreciating the good "old-fashioned" looting. It's all very much part of Furst's oft-noted "urbane" or "European" touch - that sympathy with a smile and a Gallic shrug.

... on the behemoth moving into my neighborhood: the Bush presidential library at SMU. Sorry if this is boring you. I won't keep going at it, I promise, and I'll get back to books.

But in tediously predictable fashion, the Dallas Morning News has been beating the drums for it (anything for development, anything for Republican development) and in equally predictable fashion, the campus liberals (teachers, students, Methodists) stupidly objected to it (the objections are stupid because they're being made on grounds that can only lose). Now, to complete all of this political theater, the Morning News has taken to beating up the liberal types just about every morning: what repressive elites they are, how they're closing off academic freedom, etc. In fact, the conservative think tank that will be built with the library sounds less like a research facility and more like a campaign office. Lee Cullum wrote an op-ed piece in the News, championing the library as just a new version of the respectable Hoover Institute (which, of course, ahem, she just happened to attend -- several times). Unfortunately for Lee, the NYTimes ran a piece a few days before about how presidential libraries are pretty much propaganda machines these days. And the full irony here is: Lee and the News are defending an administration that has done everything in its power to close off historical research on presidential papers.

The fact is that I don't oppose the Bush library on political grounds. Let conservative donors waste a half-billion dollars trying to resuscitate his legacy; it'll save them from spending it on more effective programs against the rest of us. No, I oppose the library because I'm going to have to live near it.

But perhaps I shouldn't complain. The library could help my drive time. A curious fact: Highland Park (where SMU is) has loudly and successfully squashed any sensible attempt to widen Mockingbird Lane, the road that runs through HP. Mockingbird Lane would be a major, cross-town artery to Love Field, the city airport -- very convenient for the rest of Dallas -- if it weren't for the power of Highland Park's rich, white residents in preventing it from being expanded to accommodate the trafffic.

Now those same residents are going to welcome what amounts to a sizable new museum and theme-park tourist attraction right on Mockingbird Lane. When people say "presidential library," they think of books, ivy-covered buildings, scholars and maybe a gift shop. Not any more, folks, they've grown gigantic. And a half-billion dollars should get the Bushes something like the Death Star of presidential libraries. I challenge the Dallas Morning News to run a sizable, aerial photo of the LBJ Library's parking lot in Austin. Maybe the paper could super-impose the entire LBJ facility over a map of Highland Park. And LBJ, remember, was widely hated when he left office. Yet that parking lot could accomodate a couple of 747s, it was built for so many visitors. If you want to check out my description, here's an aerial view of the LBJ complex and parking lot.

For some reason, Gooogle will no longer permit me to call up a satellite view of the LBJ Library. The TerraServer image isn't as good, you'll have to move around and zoom in a bit, but it's easy enough to find Longhorn Stadium. Head towards the top-right from the stadium (northeast), and the LBJ Library is the white-ish rectangle with a circle in front of it (that's a fountain) with the helipad on top (that's the little dark cross on top) and alongside the long thin building that runs diagonally across the picture. That's the LBJ School. And that huge black strip next to the school, the one that looks like hedgerows or something is the aircraft-carrier-size piece of tarmac that functions as the parking lot. The tiny white dots that look like aphids? Those are cars. Just look at all the blank spaces.

That's what Highland Park is looking forward to: All that blacktop, and all those tourists coming to the Bush Library, trying to drive over from Love Field -- on Mockingbird Lane.

So you see, the citizens of Dallas could never get Highland Park to widen that street.

But I betcha the Bushes can.

... I have a lot of meetings arranged (possible work!) and a deadline to meet (real work for money!), so the postings may get spotty over the next several days.

Plus, I haven't received any e-mail in three days. Not even spam. The longest run with no messages I've had in quite a while. Something's wrong with Comcast/TimeWarner, I'm sure, but, of course, no one answers the phone over at GlobalMediaDomination HQ. So if you HAVE e-mailed me, that's why there's been no response or I haven't posted your comment.

And all of this happens to me during National Delurking Week. If you're visiting a blog this week, you're required to write and indicate you actually read the thing. Otherwise, we kick your @ out of your e-mail address and you won't be able to send messages. Or log in. Or buy anything on eBay.

... were announced today. As usual, although there are familiar enough titles on the list, such as Cormac McCarthy's The Road or Kirin Desai's The Inheritance of Loss, which already won the Man Booker Prize, the National Book Critics Circle has chosen books that are more learned, less well-known (and one might admit, with more foreign authors) than the typical National Book Award fare. We wouldn't want it any other way. Or to put it differently: They always make me feel I didn't read enough last year.

From Critical Mass, the NBCC's blog, here are this year's nominees:

The Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing:

Winner: Steven G. Kellman

The finalists: Ron Charles, Donna Rifkind, Gideon Lewis-Kraus, Kathryn Harrison

The Sandrof Award for Lifetime Achievement:

John Leonard

Nonfiction:

Patrick Cockburn, The Occupation: War and Resistance in Iraq

Anne Fessler, The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe V. Wade

Michael Pollan, The Omnivore's Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals

Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution

Sandy Tolan, The Lemon Tree: An Arab, a Jew and the Heart of the Middle East

Fiction

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Half of a Yellow Sun

Kiran Desai, The Inheritance of Loss

Dave Eggers, What is the What

Richard Ford, The Lay of the Land

Cormac McCarthy, The Road

Memoir/Autobiography

Donald Antrim, The Afterlife

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home

Alexander Masters, Stuart: A Life Backwards

Daniel Mendelsohn, The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million

Teri Jentz, Strange Piece of Paradise

Poetry

Daisy Fried, My Brother is Getting Arrested Again

Troy Jollimore, Tom Thomson in Purgatory

Miltos Sachtouris, Poems (1945-1971)

Frederick Seidel, Ooga-Booga

W.D. Snodrass, Not for Specialists: New and Selected Poems

Criticism

Bruce Bawer, While Europe Slept: How Radical Islam Is Destroying the West From Within

Frederick Crews, Follies of the Wise: Dissenting Essays

Daniel Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion As A Natural Phenomenon

Lia Purpura, On Looking: Essays

Lawrence Wechsler, Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences

Biography

Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in Amerca: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher

Taylor Branch, At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-1968

Frederick Brown, Flaubert: A Biography

Julie Phillips, James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon

Jason Roberts, A Sense of the World: How a Blind Man Became History's Greatest Traveler

Sarah Weinman at GalleyCat has an illuminating round-up of recent stories about the backstage machinations at book awards -- including the CIA's involvement in getting the Nobel Prize to Boris Pasternak for Doctor Zhivago (we wanted to embarrass the Soviets, who'd banned the book). But perhaps the most interesting item is the way the rules for the Man Booker regularly skew what gets submitted and therefore chosen.

In case you hadn't noticed, dog books are big, thanks in part to the year-long bestsellerdom of John Grogan's Marley & Me: Life with the World's Worst Dog. "The market for good dog authors is humming," Andrew DePrisco told the Philly Inquirer. He's the editor in chief of Kennel Club Books as well as the author of -- wait for it -- Woof! A Gay Man's Guide to Dogs.

In case you hadn't noticed, dog books are big, thanks in part to the year-long bestsellerdom of John Grogan's Marley & Me: Life with the World's Worst Dog. "The market for good dog authors is humming," Andrew DePrisco told the Philly Inquirer. He's the editor in chief of Kennel Club Books as well as the author of -- wait for it -- Woof! A Gay Man's Guide to Dogs.

Knowing the mad-pack mentality of the publishing industry, I was going to suggest that, next up, we'll see Da Cute Widdle Puppy's Guide to Wuv. But today's FedEx delivery brought me this, instead: Murder Can Depress Your Dachshund. I only wish I could have made that up; Selma Eichler's book is on sale in early February.

... is an awful burden that, as you know, I bear in humble silence.

See below, the entry "Why have any editors choosing books at all?" -- the one concerning Simon & Schuster developing an online contest called First Chapters for would-be novelists to win a publishing contract. In this world of me-too American Idol! promotional ballyhoo, I noted that "the publishing industry is playing catch-up, coming to the game late, long after the gimmick has gone lame ... after even Broadway has broadcast its audition-the-nobody-to-play-the-lead-in-Grease folderol."

Now comes a New York Post story that reports the Broadway-reality-publicity TV show, You're the One That I Want has been trashed by critics, theater insiders and even viewers. Ticket sales are not taking off.

Seven years ago, my daughter told me a story about this creepy old king she'd read about, whose name she couldn't pronounce. After a few minutes, I figured out the one she was talking about. Wait, I said, that's Tiberius Caesar.

Seven years ago, my daughter told me a story about this creepy old king she'd read about, whose name she couldn't pronounce. After a few minutes, I figured out the one she was talking about. Wait, I said, that's Tiberius Caesar.

Not a bad conversation for a parent to have with a 9-year-old. Suzanna owes a lot of her whiz-kid abilities in history to Larrry Gonick and his Cartoon Histories of the Universe. Mr. Gonick has released his latest volume, The Cartoon History of the Modern World, Part 1: From Columbus to the U. S. Constitution, and it sustains the high standards set by his previous works: funny, learned, engaging, skeptical.

If you find anything labeled "cartoon history" difficult to take seriously as an adult, you're mistaken. Mr. Gonick's books are marvelous instruments of instruction and entertainment -- and they're just really smart history books, too. I cannot over-recommend them to parents of school-age kids, especially kids who are book-phobic or at least schoolbook-phobic (meaning, mostly, young boys). Parents, in the first place, should consider enticing such children into reading by letting them read comic books. Reading is reading; just get them started. My siblings and I subscribed to seven different titles back in Marvel Comics' great age of Spiderman, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four and the Silver Surfer, and the only ill-effects we've suffered come from seeing the prices our old (now lost) collection would currently fetch on the market. Besides, the earlier Cartoon Histories of the Universe dealt with all of that Biblical slaughter and illicit sex, so that should certainly interest 10-year-old boys.

But beyond the obvious kid-appeal of the Cartoon Histories, they really are a pleasure to read -- from Mr. Gonick's draftmanship to his research. In those areas of history I know something about, it's amazing to see how shrewdly Mr. Gonick has compressed entire arguments. This time, it's the global reach, the simultaneity of events that's fascinating -- like some giant, moving jigsaw puzzle. I knew, for example, that the Turks' invasion of Europe in the 15th century had influenced the wars of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. I hadn't realized how often it happened and how much the early life of Protestantism owes to those military distractions and the death of Charles V. Events could have easily been timed differently, and although it's not likely the Reformation could have been forced back into the bottle, the bloodshed might have toppled different kingdoms, affected colonial growth in different ways.

Through his balding, comic-professor narrator, Mr. Gonick conveys his own values (tolerance, clarity of thought, amusement at human folly) without clouding events. The only villains he finds are the bloodthirsty fanatics, and even then, he's often willing to grant them the efficacy of their methods. He's perfectly willing to pause the March of History to sketch in background or spend time in a footnote on the kind of wonderful detail that enlivens all that marching (how the 16th-century Venetian traveller Lodovico Varthema, for example -- the first non-Muslim known to have entered Mecca -- managed to escape a Yemen jail).

My one gripe about his books: It's easy enough to complain about the lack of this or that figure. Mr. Gonick has to cover so much ground, much of his wisdom resides in the editing, what he has to trim or mention only in passing. But overall, his histories are histories of Big Ideas and Big Events -- meaning he covers politics, religion, the military and science (both technology and theory). But not as much on culture. Occasionally, important writers will pop up, notably Shakespeare and Cervantes, and even the rare artist or architect (Michelangelo). But the other arts are mostly absent -- especially music. No Bach, no Mozart, no opera.

Mr. Gonick's subject this time, "the modern world," means mostly "the New World and Europe's growth and expansion into it" -- but that doesn't mean his books are heavily Euro-centric. Far from it. There's plenty here, for instance, on the establishment of the Sikh religion or the pre-Columbian cultures. It's just that given the explosion caused by capitalism, colonialism, technology and religious competition, the West tended to be where so much of the turmoil was. The West, for better AND worse, pretty much created "the modern," and whether that means the invention of telescope-aided astronomy or the slaughter of native peoples, Mr. Gonick manages to be a wonderful guide, both serious and light-hearted.

In a story that sounds like something out of a lesser Dickens novel, writer Ian McEwan has found an older brother he never knew he had -- a brother who, when he was an infant, was given away by McEwan's mother at the Reading railway station.

.... of "the Unfilmables" -- novels that would be near-impossible to film. What he means, of course, is impossible to film well.

The expected modernist achievements are here (Ulysses, Finnegans Wake, Samuel Beckett's Trilogy, Proust's A la recherche du temps perdu), although what isn't mentioned about Beckett is I'll Go On, the great actor Barry McGovern's brilliant (and brilliantly funny) one-man theatrical distillation of the Trilogy. Presumably, THAT could be filmed.

But strangest of all is the complete lack of anything on the list by Virginia Woolf, even though works like To the Lighthouse may be the most evanescent/impressionistic novels of the period (and yet Orlando was made into quite a good film by Sally Potter). "Anything by Thomas Pynchon" is listed -- which is nonsense; The Crying of Lot 49 could make a very interesting film. And Pynchon's old Cornell prof, Vladimir Nabokov, wrote several novels far more unfilmable than anything by his student. Consider Ada and Pale Fire.

Actually, most any lengthy novel that, following Proust, is a monument of deeply personal memory and style, would be difficult to film. I'm thinking in particular of Robert Musil's The Man Without Qualities. Of contemporary writers, people who wrote into Screen Head got most excited about Mark Danielewski's House of Leaves and David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest. I think David Mitchell's work, especially Cloud Atlas or Number9Dream, would be more difficult than Catcher in the Rye (which, oddly, is on the list). And wait till someome tries to condense this 864-page monster.

The list is fun but futile. The old maxim, "Great book, bad film; mediocre book, great film," is worth recalling here. An author's vision and style may simply be too singular, too consciously literary, to be broken into 24 frames per second.

But consider the aforementioned Orlando or Michael Winterbottom's recent adaptation of Tristram Shandy, which although strictly speaking is not much of an actual adaptation of Laurence Sterne's book, it still did a remarkable job of capturing much of Sterne's antic humor and nattering spirit. Or what about the incredible Street of Crocodiles? Who would have thought that Bruno Schulz' novel could ever have been made into a puppet film by the Brothers Quay-- and such a hallucinatory work which seemingly has nothing to do with the book and yet beautifully conveys its dark, airless surrealism?

In short, sometimes the film-credit phrase "inspired by" isn't a bad sign. Films "inspired by" books, rather than literal-minded adaptations of them, often are the best celluloid homages to great literature.

Novelist Peter Mattthiessen was a CIA agent?

While he was working at Paris Review?

To echo one person quoted in the NYTimes story: Wow. Geez.

I have very good cause to dislike Tom Delay.

Because of his behind-the-scenes work in gerrymandering Texas' voting districts,  my area lost a fine, smart, effective representative in Martin Frost, a Democract, and got stuck with the right-wing rubber-stamp Pete Sessions. Americans in general have good cause to dislike Tom DeLay, given what he has done to partisan politics. Hell, many in the Republican Party aren't too fond of him because of the way he's made the GOP into the party of pork, plunder and influence-peddling.

my area lost a fine, smart, effective representative in Martin Frost, a Democract, and got stuck with the right-wing rubber-stamp Pete Sessions. Americans in general have good cause to dislike Tom DeLay, given what he has done to partisan politics. Hell, many in the Republican Party aren't too fond of him because of the way he's made the GOP into the party of pork, plunder and influence-peddling.

But even I don't think there's any real similarity between O. J. Simpson's book -- the one that got Judith Regan fired -- and Tom DeLay's memoir, which is titled No Retreat, No Surrender. But according to a Raw Story report, a staffer inside Penguin, parent company to the conservative imprint Sentinel, claimed there was an uproar over the book, made the comparison to OJ and objected to publishing the book of an indicted man. The source compared Sentinel's editor, Bernadette Malone, and her money-minded choices to Regan.

This is pretty trivial stufff -- trivial, backbiting nonsense from what sounds like a vengeful co-worker, and hardly on par with Ms. Regan's offenses. There must be any number of authors whom Penguin publishes who have faced legal charges over the years -- and any number that individual editors might object to. Let Sentinel publish DeLay's book. The fact is, it's already a preposterous bit of defiant posturing -- that is, unless the title gets changed to No Retreat, No Surrender ... but Resigning from Office is Still Heroic and Manly.

By the way, if anyone can find the origin of that phrase, "No retreat, no surrender," I'd be curious to learn it. It's popped up in several hip-hop songs and book titles over the years (and a Babylon 5 episode), but Bartleby.com, for instance, has no source, no original quotation for it. It always struck me as what Hitler ordered the Panzerkorps to do on the Russian front, an order no sensible general would ever give or follow.

By the way, if anyone can find the origin of that phrase, "No retreat, no surrender," I'd be curious to learn it. It's popped up in several hip-hop songs and book titles over the years (and a Babylon 5 episode), but Bartleby.com, for instance, has no source, no original quotation for it. It always struck me as what Hitler ordered the Panzerkorps to do on the Russian front, an order no sensible general would ever give or follow.

In any event, whatever the phrase's source, I will now always associate Tom DeLay with Jean-Claude van Damme's 1986 debut in martial arts flickery, No Retreat, No Surrender, a film so completely cheeseball, it makes the famously wooden van Damme's later cinematic efforts look like genius.

It's a Literary-Reality TV-Internet-Gameshow! Or something.

Touchstone, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, has joined Gather.com to hold the First Chapters contest for a first novel. The winner, voted on by members of the website, will eventually get published. Typically, the NYTimes article addresses the worries of agents on how this whole process excludes them. Nothing about what S&S's editors feel.

Actually, I wouldn't mind the book industry resorting to such American Idol theatrics. It's a publicity sideshow, trying to treat undiscovered writers like pop stars, and it will remain a sideshow (it's not even on network TV). But like that televised popularity contest, the Quill Awards, the publishing industry is playing catch-up, coming to the game late, long after the gimmick has gone lame. The Quills appeared when the flood of televised awards shows had become dead weights in audience ratings, and now First Chapters arrives, after even Broadway has broadcast its audition-the-nobody-to-play-the-lead-in-Grease folderol.

My new reality TV-book pitch? Hide a literary agent with a lucrative publishing contract on a jungle island. Crash land a group of troubled-but-of-course- Hollywood-attractive, would-be writers there (with a camera crew) and release some unspecified monster that starts killing them gruesomely one by one. Copy editors or book critics might volunteer for this role.

The trick? Each author has been given part of a coded map that can lead them to the agent. And only the agent knows how to kill the monster -- as well as get the author a movie option. All this will require teamwork, obviously, because the longer it takes the writers to find the agent, the more time the agent will have to spend the advance and screw up the movie rights.

But only one writer will get published. So the writers need to work together, and they need to feed each other to the monster. Kind of like literary life in New York.

At any rate, the really important thing, as the Quill Awards like to point out, is that all this idiocy will somehow encourage people to read.

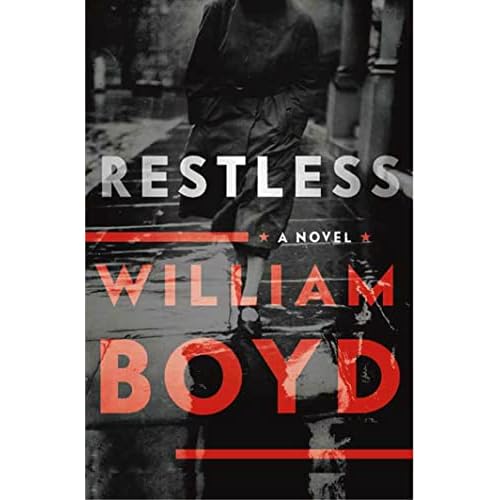

William Boyd's Restless -- which I praised by placing it alongside the best of Graham Greene and John le Carre (see in the archives, "I Spy, too") -- has won the Costa Prize in England. You've never heard of the Costa prize because it's actually the old Whitbread, now underwritten by a London (originally Italian) coffee company. It's the second Costa/Whitbread for Boyd, a very rare event (Seamus Heaney, for instance, failed to win his second prize this year), and still a surprising one: Restless is a quiet, graceful spy thriller, not the sort of thing that normally wins big awards.

William Boyd's Restless -- which I praised by placing it alongside the best of Graham Greene and John le Carre (see in the archives, "I Spy, too") -- has won the Costa Prize in England. You've never heard of the Costa prize because it's actually the old Whitbread, now underwritten by a London (originally Italian) coffee company. It's the second Costa/Whitbread for Boyd, a very rare event (Seamus Heaney, for instance, failed to win his second prize this year), and still a surprising one: Restless is a quiet, graceful spy thriller, not the sort of thing that normally wins big awards.

You gotta wonder about this guy writing anyone's "authorized" biography again. "Venomous"? "Vindictive"? "Grandiose"?

After Nadine Gordimer objected to Roberts' No Cold Kitchen, her authorized bio, Farrar Straus & Giroux in America and Bloomsbury in England refused to publish it. Got all sorts of international attention, including in the NYTimes. He claimed she objected to his printing several letters that said unflattering things about fellow anti-apartheid activists and authors, such as Doris Lessing.

But in her blog, ambainny put the dispute in the context of "the uncertain role of white anti-apartheid activists now that the African National Congress has become the government. Gordimer, who has been active with the A.N.C. since the '70s, when it was an illegal organization, may still be lionized abroad, but at home she finds herself criticized from all sides."

On the other hand, in this separate case, the judge simply found Roberts to be a tremendous jerk.

Over at the Making Light website, they've run a "devil's dictionary" of publishing-industry definitions (inspired by the one at Paperback Writer, which is in archives that I can't access).

This dictionary generally lacks Ambrose Bierce's wonderfully succinct viciousness. Some entries are too long-winded, some rather obvious ("Trade Publisher: A publisher of books that are sold via bookstores" -- yes, and the punchline is?).

But some are very smart ("Self-publishing: How authors who are slow learners find out about marketing and distribution").

... here's reviewer Jan Miller in Poets & Writers on practical techniques for publicists (and authors) to work with freelance literary journalists, basic things that many fail to follow (like "know our calendar"). My post last month ("It's the system that's the monster" in archives) actually concerned the way the publishing industry exploits young, underpaid assistants (just as journalism and movie-making do). But some of the attention it gained on the internet came from my characterization of many assistants as office cannon fodder. Because they have to serve canapes at book release parties, schedule book tours, cold-call the media, write press releases, ferry manuscripts and do a million other office (and late-night and weekend) drudgeries, they often aren't that knowledgeable or helpful to journalists because they simply can't keep up with the deluge. And this, it seemed to me, is a wretched way to handle publicity and, lest we forget, intelligent human beings.

In her gentle way, Ms. Miller more or less confirms this. I might add that whatever Ms. Miller has experienced as a freelancer, it's one-twentieth of what hits a newspaper's book office and voicemail.

A front-page story appeared in today's Dallas Morning News about the Bush presidential library that -- in all likelihood -- will be built just across Central Expressway from my house. The Morning News has already gone on record in an editorial hailing the Bush library as a future turning point for Dallas as an intellectual and scholarly center. Don't laugh -- it could happen. Maybe. LBJ was hardly beloved when his library opened in Austin, and it has proved to be a fat importer of money, events and authors. Not that it exactly "turned Austin around" as a university town, but you get the picture.

For its part, today's lengthy feature never mentions a) the library's estimated half-billion dollar price tag, by far the costliest presidential library in history and b) the fact that much of the money, according to the Daily News will go to building a conservative think tank, which characteristic of this secretive, punitive administration, will be dedicated, not to open scholarly research but to refurbishing Bush's place in history.

What's more, in the Morning News, a little feature sidebar on President Bush's "Key Actions" mentions a number of his more "controversial" accomplishments -- the kinds of things that the think tank is going to have to clean up, nice and shiny. But the sidebar uses such benign-sounding phrases as "protected the U.S. homeland against further terrorist attacks after 9/11," "enlarged the powers of the presidency," "authorized the surveillance of overseas telephone calls of terror suspects" and "established prisons for terror suspects in Europe and Guantanamo Bay."

Somewhere in those phrases are squeezed: Abu Ghraib, illegal renditions, the "cherry picking" of intelligence until our espionage services rebelled, torture, the Padilla case (so cynically and badly handled by the Bush justice department a conservative judge blew up at them), the opening of mail without a warrant, the stonewalling of Congressional inquiries into all of this, the failure to catch Osama bin Laden or any new terrorist cell in America, the abuse of "presidential signing statements" to undercut any law Bush disagrees with and the fact that the overseas telephone surveillance was pretty much wholesale, not targeted at specific suspects. Oh yes, and the cynical ballooning of the federal deficit.

At this rate, I don't see why we'll need that conservative think tank to whitewash the Bush legacy.

In the American crime novel, the detective is often world-wearily aware of how his city really works: the corruption in government, corporate dealings, law enforcement. The fix is in.

In short, the American noir detective is often a failed romantic: The world doesn't fit his ideals, so he has taken to drinking and making surly wisecracks about women, the rich, cops on the take. One of the remarkable achievements in Vikram Chandra's stunning new novel, Sacred Games is its portrayal of the all-encompassing, ingrained nature of the corruption in Mumbai (formerly Bombay). Everything is up for grabs, everything can be paid for -- over or under the table: police work, civic infrastucture, career advancement. And this is completely understood and accepted. It's even exalted as an extension of the aggressively entreprenerial, eat-or-be-eaten spirit of the city. The fat envelope is always ready. "Cash creates beauty," says one character, "cash gives freedom, cash makes morality possible."

And yet there's dignity and merriment in this darkness. Chandra's detective, Inspector Sartaj Singh, is immersed in this mordant world, but he's neither completely corrupted by it nor paralyzed by cynicism. He takes bribes (it's the way the system works), but he's modest about it. He's a Sikh, a would-be family man, proud of his traditions and his investigative skills (his father was a police officer, too). Sacred Games is hardly the first crime novel set in India -- consider H. R. F. Keating's Inspector Ghote series -- but it is a landmark work, a novel so ambitious and fully achieved it makes most American crime novelists -- the Lehanes, the Pelecanos, even the Ellroys -- seem naive and timid by comparison. This second novel from the author of Red Earth and Pouring Rain is a lurid epic of gangland bloodbaths, squalid poverty, movieland prostitution and religious fanaticism. But at its heart, it's an affectionate portrait of Mumbai: "this labyrinth of hovels and homes, this entanglement of roads," this Third World Oz, this impossible explosion of polyglot possibilities, of languages, faiths and hatreds.

Along the way, Sacred Games becomes something of a history of modern-day India, too (the title refers to both the country's religious background and the old 'Great Game' between Russia and Britain for control of India). Inspector Singh is tipped-off to the whereabouts of a tabloid-famous mob leader, but when he tries to arrest Ganesh Gaitonde in his bunker hideout, Ganesh kills himself first. Inspector Singh sets out to learn why.

The novel then becomes partly narrated by a dead man (India is too fantastical, too god-driven, to be conveyed by ordinary, crime-novel realism). In alternate chapters, the spirit of Gaitonde relates his own hungry rise to power, a rise that, as Singh discovers, involved wholesale smuggling, bankrolling politicians as well as Bollywood movies and, ultimately, doing dirty work for the Indian government's intelligence service. What was a police procedural and then a ghostly Godfather saga becomes a John le Carre espionage-cliffhanger. Inspector Singh finds that the bitter, Cold War-like stand-off between Pakistan and India -- between Islamic fundamentalism and radical Hindu nationalism -- has entered the era of nuclear terrorism.

For many American readers, Sacred Games will present a sizable and instant turn-off: 900 pages long with a bewildering foreign setting, a (very necessary) glossary of hundreds of Hindu and Indian terms, plus a partial index of charcters (only 36 are listed -- there are probably close to twice that by name in the novel). Even so, HarperCollins reportedly paid $1 million for Chandra's book (a best-seller in India). Indeed, its popular-commercial prospects are actually quite plain. As much as it is a multi-lingual dazzler of ambitious fiction, it's a rich, riveting thriller.

And the fact is that many readers seek out precisely this kind of full-immersion experience in a novel, an education into an entire world different from their own. Sacred Games more than supplies this -- here, there is family, faith, a romantic affair, a sexual obsession, blackmail, betrayal, a city on the brink of chaos, and all of it is lyrically, lovingly conveyed. Sacred Games is one of the very few 900-page novels of recent vintage that as I read it, I was always eager for more.

In its recent story about the demise of the Micawber bookstore in Princeton, the NYTimes quotes owner Logan Fox to the effect that "he can't quite pinpoint the moment when movies and television shows replaced books as the cultural topics people liked to talk about over dinner, at cocktail parties, at work. He does know that at Micawber Books, his 26-year-old independent bookstore here that is to close for good in March, his own employees prefer to come in every morning and gossip about "Survivor" or "that fashion reality show" whose title he can't quite place."

Actually, books have rarely been a topic of conversation in offices or parties -- unless it's among a select group of people who just happen to be avid readers and who happen to have read the book under discussion or at least read reviews of it or perhaps an interview with the author or perhaps even just an earlier work by her. If you think about that, you realize how small or rare such a happenstance would be. If you're already hammering away at your keyboard to tell me how wrong I am, how you enjoy such casual bookchat everyday at work, you must realize how fortunate/educated/isolated you are. It's a chief reason people join bookclubs or attend literary series in the first place: They don't have enough ordinary literary discussion in their lives, so they have to organize some.

No, this isn't another diatribe about rampant illiteracy, the decline of books in our culture vs. the rise of the no-attention-span internet or the graphic zap of computer games. Books and bookchat have always been like this for a simple reason: It's extremely rare that any book achieves the kind of near-instantaneous cultural penetration that a movie or TV show or sports spectacular does -- only a new Harry Potter or Bill Clinton's memoir gets that kind of saturated exposure, and it requires that kind of everyone's-heard-about-it impact to spark casual conversation.

Instant cultural saturation occurs partly because of the economics and mass-media distrubution systems that favor TV, movies and the internet. It's hard to compete for people's attention against a billion-dollar conglomerate like Sony when it has gambled several hundred million on a new film, and all you've got it is a good memoir and a few bookstore readings lined up. Sony must achieve that sense of it's everywhere! it's everywhere! with all the TV ads, fastfood tie-ins and talkshow interviews in order for their investment to pay off. The entire onslaught is designed to make their film or DVD release an undeniable cultural presence, something people feel they have to know about because it's self-evidently important: There's an action figure with the show's name on it at every Wal-Mart and Taco Bell.

But this unfair advantage has existed for decades, long before Sony and the development of the blockbuster opening weekend, because of the nature of books and publishing. Books take time -- time to read, time to disperse, time to find their audience. Let's say 15 thousand people will buy and read a hardcover when it comes out. If it gets great press and word of mouth, maybe 20-50 thousand more will wait until it comes out in paperback -- next year. Or they'll wait until it's available at their library. Or until they can borrow a copy from a friend.

All of this makes for an extremely diffuse "opening." The same is true of live performing arts -- theater or dance -- or museum exhibitions. And this has been the case for at least as long as modern publishing and touring have existed. For books, limited access plus long-term aesthetic experience = slow public impact. My friend John Habich, fine arts editor at Newsday, first explained to me this now-rather obvious phenomenon. It's why he helped create Talking Volumes when he was at the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Talking Volumes is a joint venture among the Star Tribune, Minnesota Public Radio and the Loft Literary Center. An author is chosen and comes to town for several days or a week. The newspaper plans a major profile, Minnesota Public Radio has an on-air chat, there are bookstore readings, library visits, etc -- all in that same window of time, giving the author and his book the kind of community exposure that only a new big-budget film or hit TV series generally gets.

Book publicists wish this kind of coordinated attention would happen any time an author comes to a major city, but it rarely does and never for this kind of extended period of time, a whole weekend or even a week. Newspapers, TV and radio stations are bombarded by every cookbook and self-help author around, who often have their own PR flaks cluttering up the voicemail, in addition to the book publicist's own efforts, so it's all much more sporadic and piecemeal, rarely this thoughtful, this multi-layered. It's difficult for many TV and radio people even to make the choice, that this author deserves attention amidst all the swarm. There will be another swarm the next day and the next, and who knows enough about books and authors and publishing, who has the judgment to make that decision -- this is worth two minutes' on-air time because it'll prompt people to talk about it for days around the water cooler at work?

This morning in The Dallas Morning News, editor Bob Mong explained some of the changes that will be appearing in the paper soon, changes that we, the readers, supposedly requested. Bigger, more colorful comics, the return of the 500 most active stock index, etc.

Nowhere is any explanation given for the reduced arts coverage, especially when it's now the stated purpose of the paper "to provide local news and information that you can't find anywhere else." The likely reply would be that it hasn't been reduced -- it has the same space. But with the departure of both TV critics, the visual arts critic, the architecture critic, the pop music editor, the film critic, the arts editor, the books editor and, yes, the book critic (me), the Morning News now presents David Kronke -- of the Los Angeles Daily News -- as its de facto TV critic (meaning pretty much no local TV coverage), John Freeman, a fine freelancer, as its lead book critic and any warm body from the Associated Press or one of the LA papers or the Washington Post as a film critic du jour.

Yes, it's a changed media world for daily newspapers everywhere. Yet no one in a position of authority at any paper has managed to explain why the sections that serious readers would be interested in -- the kind of well-off, educated, committted readers whom newspapers would want to keep with in-depth coverage of politics, the arts, books, lengthier feature stories -- why those are precisely the sections that are getting cut? When the mantra was "chase the younger reader," those sections got cut because teens don't read that stuff. Management finally realized that trying to give young people who don't read even less to read wasn't working. So "local is best" became the new theory (one that makes a fair amount of sense to me) -- and those sections still get cut.

In Dallas, when a marvelous advance -- a freestanding daily arts section called GuideLive (yes, a stupid name -- tell that to the marketers) -- was first proposed, designed and tested, the response from management and its sainted focus groups and surveys was overwhelmingly positive. Ad revenue from the movie companies even increased. Let's repeat that: Increased ad revenue in a daily newspaper. Yet all of those facts in favor of better cultural coverage vanished when the new banner of "local is best" was hoisted.

The problem for newspaper arts coverage has little to do with editors' fears of cultural ignorance or what readers want. The problem has to do with the fact that local arts (and book publishing) do not generate much ad revenue. That might explain why the only critic that the DaMN is currently replacing with someone actually in town is -- the restaurant critic. Restaurants provide ad revenue.

Even so, in most major cities, the daily newspaper remains the only single place one can find local arts coverage of a thoughtful quality, and all of it -- dance, opera, pop music, TV, theater, books, film -- all of it in one place. No website I've found (other than the wretchedly designed ones put up by newspapers) manages anything like that breadth, that "connectivity" among a city's arts and its national and even international peers. The result in city after city that I visit is that while the daily paper is whittling away at its local cultural coverage, TV does next to nothing except happy puff pieces, radio does next to nothing locally (and this often but not always includes the area PBS and NPR stations), the city magazine does the occasional tout or glossy profile but no serious sustained coverage (not the way it covers restaurants) and the alternative weekly paper covers pop bands, nightclubs, local theater and food but little else other than the occasional profile or news feature, provided the coverage can be made aggressively, even pointlessly controversial.

This is now (more or less) the rule for local arts coverage in print in America. There are profound exceptions, of course, and people may tout this PBS station or that alternative weekly or even two daily papers locked in sufficient competition that they actually try to top each other when it comes to discussions about authors and artists. But they are exceptions, and I don't see the internet, with its intense, bifurcated development of personal blogs and corporate distrubution systems (just books, just theater, just pop music), providing the same kind of city-wide discussion or spotlight. Before this, it was very hard for live performing arts (theater, dance, opera) or slow-impact arts (books, museums) to cut through the opening-weekend, mass-market, sweeps-week, billion-dollar clutter of the media.

Now, I don't know how any of them manage it.