book/daddy: November 2006 Archives

In that same December issue of The Atlantic Monthly with its list of Uninteresting Americans (see below: A Hole in the Atlantic), Virginia Postrel argues that chain stores are good for us.

There's much to be said for chains. As irrritatingly ubiquitous as it is, Starbucks, for instance, has transformed coffee in this country, generally for the better. Twenty years ago, good-quality cappucinos and lattes were nearly nonexistent in many parts. And before there was Amazon.com, the bookstore chains Borders and Barnes & Noble brought a wide range of literature to many areas of the country that had never seen so many books before.

But chain improvements often come with a price. Starbucks, for instance, charges a steep toll for a cup of ordinary joe. In Ms. Postrel's hometown of Dallas, I can go to Wild about Harry's, a favorite local hot-dog-and-custard stand, and buy a nice coffee for 95 cents. Less than a block away, Starbucks will sell me pretty much the same thing for nearly three times that amount. And it's Starbucks' prices that one increasingly sees in coffeehouses across America.

As is characteristic of Ms. Postrel -- who makes much of her living enthusiastically defending suburbia and the great changes wrought by corporate commercialism --she wisks away this kind of unpleasantness. Her article's basic argument is that the widespread notion that chains have increased the "sameness" of America -- made it all so cookie-cutter boring that it has become "the geography of nowhere" -- that notion is completely wrong. Even if it weren't wrong, this kind of gloomy liberal-urban-media snobbery always seems to set her teeth on edge.

And she's right. There's still a lot of local color out there, if one looks beyond the 7-11 clutter. And the 'lost' local color we often pine for was precisely the kind that wouldn't have wanted most of us: It was small-minded, xenophobic. Also, for many people in small towns, a new, nearby Best Buy -- as with a new Borders -- has often meant a major uptick in convenience and wider access to goods.

Let's not get into what a new Wal-Mart has or has not meant for them.

The problem is that Ms. Postrel makes it easy on her chainstores-are-wonderful argument. She goes to Chandler, Arizona, outside of Phoenix, and notes that even with all those same-same-same chains, the town is still very distinct from, say, New England or the Carolinas.

Yes, one must admit that the Arizona desert is a wee bit different from New England's wet pine trees. But if Ms. Postrel were suddenly transported to a mysterious subdivision of my choosing, she would be hard-pressed, I would think, to tell if she were in a northern suburb of Dallas, a northern suburb of Houston or a northern suburb of San Antonio (unless a sign told her). And those three cities are in distinct physiographic areas -- from blackland prairie to sub-tropical grassland to Texas' Hill Country.

For those people who think, well, that's just three cities in Texas -- not fully grasping how wildly various the geography is in the Lone Star State -- we can shift our test to three Midwestern states. I sincerely doubt it's all that easy to distinguish portions of many of the suburbs of Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinatti, Toledo and Chicago. I've been there.

It's revealing that in her description of Chandler, Ms. Postrel doesn't linger over the fact that it's no longer a farm community. She's not one for that kind of back-to-the-earth nostalgia, and neither am I. But it's also a necessary part of her change-is-good strategy: Ms. Postrel must denigrate what we've "lost." The local "mom & pop" retailers were unimpressive, and it's no great shakes that they went under: "The range of retailing ideas in any given town was rarely that great. One deli or diner or lunch counter or cafeteria was pretty much like every other one. A hardware store was a hardware store."

One wonders if Ms. Postrel has ever looked through a hardware store for something other than an appliance or a name-brand house paint. Even the chains -- other than Lowe's or Home Depot -- can be significantly different. In Dallas, one will search futilely for particular brackets or specialty bolts in an Ace Hardware, but one will most likely find them at Elliott's, which has an impressive stock of oddities and doohickies, although not as many paint options as the big chains. In Detroit, where I grew up, hardware stores, not unexpectedly, sold a much wider range of automotive parts than one finds today in any Home Depot. Conversely, other Detroit hardware stores were little more than lumber yards with some plumbing supplies on the side. I am not arguing that any of these were better than a Home Depot, but contra Ms. Postrel, they had very different, very individual inventories.

What makes Ms. Postrel's arguments often so challenging -- why she regularly finds work at places like The Atlantic -- is her eagerness to get beyond the usual mindsets. She was for the war in Iraq, for example, and voted for Bush, but, frankly, never liked him much -- a position that has the added bonus of leaving her unsurprised and not particularly disillusioned when it became plain that Bush misled the country about ... well, about all those reasons Ms. Postrel must have had for going to war.

Ms. Postrel almost always does battle with the Received Wisdom (generally liberal but not always) because the Received Wisdon, by its nature, is statist and she, as her website declares, is a happy "dynamist" (her term). Hers is a very American enthusiasm: Let us ride the waves of change. Change is progress, the future is good, new technology is good, the free market that delivers new goods and change is good. Anyone who questions these syllogisms is grumpy, backwards-looking, repressive and un-American.

What often makes Ms. Postrel's energetic arguments irksome, however, is her determined obliviousness to any downside to the free market or mass-market values. Sell the people what they want; stick another Gap store in there. CEOs deserve the rewards they can get from their chums on the board, no matter how poor their company performs, because that's the law of supply and demand.

Because this post has gone on long enough, you'll have to go to the jump to read my "Grumpy Background Disclosure."

Finally finished my backyard fence (or at least the section I've been slowly replacing). Today, the prediction is for a huge "blue norther" cold front to come through and push everything below freezing by tonight, a drop of 40 degrees in half a day (on some past occasions, that's happened in less than an hour).

This is how fall and winter come to Dallas: simultaneously. I'd post a photo of the wooden fence if I could figure out how to reduce its memory size. The last time I put up a personal photo, I nearly crashed artsjournal.com.

When it gets built, I'll live less than a mile away from this thing: the George W. Bush Presidential Library. It has been apparent for months from reports in The Dallas Morning News that Southern Methodist University was the frontrunner for the Bush legacy archive (Laura Bush, a graduate, is on the university's board). But the New York Daily News finally reveals what SMU is eagerly getting itself into: President Bush and his supporters plan to raise a record-breaking half a billion dollars for the building.

In comparison, the President Clinton library in Arkansas cost $165 million, one-third the Bush price tag. Insert a whole week's worth of late-night comedians' jokes here about President Bush's reading habits.

But all that money isn't for buying up every existing copy of The Pet Goat (the children's book President Bush read to a Florida classroom after being told of the World Trade Center attack). According to the Daily News, SMU will be getting, in addition to the library, a sizable conservative institute set up purposely just to redeem the Bush administration's historical reputation.

They're gonna need the money.

Thomas Harris will be coming out with a new Hannibal Lecter novel next week -- Hannibal Rising.

Here's my prediction: It will get ecstatic reviews from major media outlets in America, just as Hannibal did, and it will be, just as Hannibal was, absolutely dreadful. A letdown, a botch.

Here's my prediction: It will get ecstatic reviews from major media outlets in America, just as Hannibal did, and it will be, just as Hannibal was, absolutely dreadful. A letdown, a botch.

That's because Mr. Harris did not understand what made The Silence of the Lambs the special piece of popcorn entertainment it was. Most people didn't. It wasn't just Hannibal Lecter that made the story. Sorry, but a mastermind killer with the pretensions of an aristocratic aesthete is as old as Professor Moriarty -- although Hannibal does have a joie de vivre that most twisted, sexual predators just seem to lack somehow.

No, what made Silence succeed so well, what director Jonathan Demme and screenwriter Ted Tally understood and Mr. Harris didn't, is that the story is really Clarice Starling's. It's her small-town woman's embarrassment and anguish we feel, it's her character that doesn't just survive despite the odds (as is typical of most conventional thriller heroines). She changes; she triumphs in the all-male law enforcement world; she faces down the lonely, impoverished family past that haunts her. After all, the title of the book is about her, not Lecter.

That's what made Silence superior to Red Dragon, and it helps explain Jody Foster's fine performance. Anthony Hopkins had the delightfully (chillingly) show-offy role; Foster submerged herself into this troubled but determined young woman. It's an inspiring piece of acting.

The evidence that Mr. Harris didn't realize this is the particularly ugly, belittling way he handled Starling in the sequel, Hannibal, and the baroque, gross-out nature of that book's violence.

When one reads the three Lecter novels in a row, it's plain that, much like Darth Vader's character in Star Wars, Lecter is something of a sideshow who took over the main event. Mr. Harris discovers his potential as he goes along; at first, he seems the logical next step in the gimmicky 'profiler vs. serial killer' sweepstakes that took over thrillers in the '80s and '90s: The FBI profilers actually use one serial killer to find another. But this serial killer proved much more interesting than the by-now-typical "sympathetic" mass murderer, the Red Dragon. That's because this serial killer is a psychiatrist, he's brilliantly self-conscious -- not only can he play the usual cat-and-mouse games with the cops, he can actually explain what's going on, what motivates the police, what drives his fellow killers. And all this comes full flower in Silence.

But with Hannibal, not only did Mr. Harris add nothing new, he seemed to think, as so many others did, that his books' appeal lay in their gruesome inventions and in Lecter's artsy disdain and gourmet snobbery. So all of these were taken to laughably ridiculous lengths in the third book.

One final reason for the predicted failure of Hannibal Rising: A real key to Lecter's allure is the way he seems to spring immediately into view, already confident of his own genius and artistry (although not yet in full control of his destiny -- that comes in Silence). We get to learn all the sad, sordid, grubby details that lead to a Red Dragon or to a Buffalo Bill, the details that make them pathetically human even as they are monstrous. But Hannibal? He's above it all, a superhuman mystery. To explain him would be like explaining Michelangelo. Art critics and historians can certainly do that, but they don't do it in a thriller. It will only diminish a fictional creation by trying to make him "real." Or we'll get one of those silly Hollywood moments when the great composer sits at the piano, lost in thought, hits a few random notes -- and that's it! It's Rhapsody in Blue!

In other words, it's no explanation at all. But that's precisely what Mr. Harris is setting out to do: Explain Lecter. Explain the explainer. His title for the third novel, Hannibal, seemed thuddingly pedestrian as it was. Now, the uninventive title for the fourth book, Hannibal Rising, betrays what I believe will be a sadly flat-footed approach to what once was a sparklingly sinister creation.

Of course, I'm hoping I'm wrong. But I'm not betting on it.

The Atlantic Monthly's cover story this month lists the 100 "most influential Americans." The novelists selected are completely unsurprising -- Twain, Faulkner, Hemingway, Steinbeck, etc. -- and the side lists for poets (Plath, Whitman) and critics (Greenberg, Jarrell) allow the 10 historian-judges to expand things beyond such a tight set. The only black author of any kind, by the way, is Frederick Douglass.

As a scholar once pointed out to me, when you get a group together to assemble one of these lists, everyone can generally agree on the first 25 people or so. After that, things get interesting or quirky or complicated. It's extremely easy to find gaps, to complain about important individuals left out. It's often more interesting to try to suss out the overall reasoning that led repeatedly to this kind of person being chosen over that one. But the Atlantic's is is a pretty unsurprising list overall and the story's attempt to define "influential" doesn't overwhelm one.

Only three things leapt out at me immediately: No actors. Authors and artists and film directors and composers are here but not a single actor. One could argue that more people around the world have gotten their understanding of what it means to be an American from Jimmy Stewart, John Wayne and Katherine Hepburn (or W. C. Fields and the Marx Brothers) than from dozens of the political figures included.

And no economists. Not that that's a great loss. It only surprised me because of the recent death of Milton Friedman and the dozens of obituaries that hailed him as such a titan of liberty and freedom -- obituaries that pretty much toed the conservative-libertarian line and ignored the fact that this messiah of the free market as a cure-all had supported the New Deal's relief programs. But that's only because the Depression, he wrote, was an extreme case, an exception. What that makes of the Panic of 1837 ("the land stinks of suicide," Emerson wrote at the time), the Panic of 1873 and the Panic of 1893 is a good question.

In any event, Mr. Friedman didn't make the list but neither did Paul Samuelson, Arthur Laffer (thank God) or John Kenneth Galbraith.

Neither did any playwright or Broadway musical creator. Which seems only typical after the complete lack of actors. Yes, George Gershwin is included but that's mostly for his boundary-breaking with jazz and classical music. In other words, the Broadway musical may be as distinctively an American creation as jazz or rock or the comic book or blues or gospel, but Rodgers and Hart, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Frank Loesser and Stephen Sondheim didn't rate. Hell, as the saying goes, Irving Berlin is the American songbook, and he's not even here.

Neither is Eugene O'Neill or Tennessee Williams. Or Arthur Miller or David Mamet or Edward Albee.

Conclusion: Someone has a definite blindspot when it comes to theater.

A late addition: The lack of Edgar Allan Poe is also curious. Not as poet or critic or fantasist. But as the inventor of the detective story, another hugely popular art form that America created.

The magazine writer Grover Lewis plans to write a memoir partly because his fellow Texas geek, Larry McMurtry, had been "Lonesome Doved" -- rewarded for abandoning his contemporary fiction for "a mythic novel based on an old screenplay about archetypcal cowboys."

"So Grover had a little litany that he had clearly worked up ... 'They will admire you for writing about the pesent, oh yeah. But they will love you for writing about the past. They will praise you for writing about housewives and showgirls, bookworms and businessmen. But they will pay you for cowboys and rednecks. They will admire you for writing about the world before your eyes. But they will adore you for spilling your guts. And somehow,' he said, 'I'll subvert that crap and still write this book.' Bam! He hit the table with his hand. It was the only violent gesture I ever saw him make."

-- from "Magazine Writer" in Air Guitar by Dave Hickey

... is true. The author of Tuesdays with Morrie does indeed write at a third-grade level.

By coincidence, at least three books this year have fulfilled the Graham Greene-John le Carre aesthetic much more satisfyingly than either of the Robert Littell spy novels I recently read-- despite all the attention and reviewers' praise that Legends and The Company received when they first appeared. All three are more modest, more emotionally affecting, intriguing and, needless to say, more stylistically interesting than the rather programmatic Littells.

To begin with the one that's most like a genre spy novel: William Boyd's  Restless is a period piece concerning Britain's little-known undercover operations in the U.S. prior to Pearl Harbor -- these were sizable propaganda and disinformation efforts to persuade America to enter the war against the Nazis.

Restless is a period piece concerning Britain's little-known undercover operations in the U.S. prior to Pearl Harbor -- these were sizable propaganda and disinformation efforts to persuade America to enter the war against the Nazis.

Told in a two-track fashion, Restless alternates between the story of Ruth, an Oxford history grad making ends meet teaching English to immigrants in the late '70s, and her aged mother Sally, who starts acting strangely paranoid. Ruth eventually learns that much of her family life was a fake: Sally isn't even Sally. She was a World War II spy, a Russian emigre in France who was hired by the British secret service (she wanted to avenge her murdered brother) and who took on a British identity. Decades later, a badly compromised operation that Sally undertook in America seems to be catching up with her: She thinks the traitor she discovered back then has finally tracked her down.

Restless is highly entertaining in that somber but suspenseful manner the British do well. The setting moves from France to England to New York to New Mexico and there are a number of sub-plot complications -- Ruth has visitors staying with her from Germany, one of whom may be smuggling drugs or may be a distant member of the Baader-Meinhof gang -- but the novel feels small and tightly-focused like a family drama. It's really about only three people: Ruth, Sally and Romer, the man who brought Sally into the wartime undercover trade.

In an earlier posting -- I Spy -- I argued that the best espionage novels generally relate some variant of three different stories, the story of betrayal, brutalization or sacrifice. Many also depict what I'd call the persistence of history. Some personal, political or professional event in the past cannot be escaped. In many cases, this simply means that the Cold War's demands are inexorable and ruthless or the longstanding clash between nations still chews up individuals, despite their best intentions.

But obviously, history's continued grip on the present is often a matter of old secrets or unfolding conspiracies. The chickens coming home to roost, as it were. It's hardly an accident that the master ironists of the so-called "paranoid" school -- Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo -- often use the equipment of noir-ish espionage thrillers: codes, secret agencies, government murder plots, terrorists, double agents and the like, just as Vladimir Nabokov repeatedly used the elements of the murder mystery in novel after novel. Consider Gravity's Rainbow, The Crying of Lot 49 or Running Dog and Libra. In fact, in Underworld, DeLillo calls all this "dietrologia," the "science of dark forces," the science of what lies behind events. It's an apt 'term of art' for the spy novel.

Obviously, Restless is an affecting demonstration of this, with its intertwining of past and (roughly) present. So, too, in a very different (but still disturbing) fashion is Forgetfulness by Ward Just-- up next.

Henry Adams was probably the best-connected American journalist in history -- the grandson and great-grandson of presidents, the son of a Congressman and ambassador. But this is what he had to say about his own unfocused abilities and his subsequent slide into journalism:

"No young man had a larger acquaintance and relationship than Henry Adams, yet he knew no one who could help him. He was for sale, in the open market. So were many of his friends. All the world knew it, and knew too that they were cheap, to be bought at the price of a mechanic."

... but in the TLS, Christopher Hitchens quotes critic Clive James in his new memoir, North Face of Soho (still available only in the UK):

The publisher's advance was more like a retreat.

My apologies. I haven't been posting as prolifically the past week and a half because I have been working on a Robert Frost-like project -- I've been replacing our old backyard fence, section by section.

But book/daddy, you say, fence building with your bad shoulder? Dare you? Exactly. I'm doing it carefully and slowly. Which explains my more-intermittent-than-usual book/daddy appearances lately.

All that stuff about Judith Regan publishing O. J. Simpson's "confession"? And FOX News running a TV interview?

They ain't gonna happen. Rupert Murdoch stopped the presses, pulled the plug.

See, he does too have a conscience. Or perhaps he just backs down when enough of his own TV stations balk. But one wonders now how long Ms. Regan will remain at HarperCollins.

... Critical Mass goes ca-razy for Pynchon (the lead item on Sunday, the second long item on Saturday, the giveaway on Friday). Michiko Kakutani does not.

Very interesting argument for the cultural significance of Gold Medal Books -- those original paperbacks that came out in the early '50s. They were hardly the first lurid cheapies nor were they the first big-selling paperbacks. But it may "not be an overstatement to assert that Gold Medal had a greater impact on the content and form of American fiction-writing than any other postwar book publisher. ... get a gander at some of the writers Gold Medal put into print: Elmore Leonard, Peter Rabe, Kurt Vonnegut, Day Keene, Jim Thompson, William Goldman, John D. MacDonald, Louis L'Amour, David Goodis, Richard Matheson, Charles Williams, and John Faulkner (William's brother)."

The Katie Awards are Texas' leading journalism prize, presented by the Dallas Press Club, although that doesn't really indicate their size or significance -- newspapers, radio and TV stations in Oklahoma, Arkansas, New Mexico, Colorado and Louisiana have also been competing for years, making the Katies, despite their weaknesses, the closest thing to a "regional Pulitzer."

Unlike the Pulitzers, however, the Katies are broken up into some 200 categories -- categories for specialty papers, podcasts, public relation campaigns, spot news photography, cover design, layout, video photography, video editing, plus all the different kinds of writing and reporting (business, sports, humor, editorial). There have been attempts to rein in the number of categories in recent years, sometimes with disastrous results. Two years ago, they killed pretty much all the separate arts categories. Then they reinstated a number of them.

I should add that for the past five years or so, the Morning News management has played down any importance to the Katies -- for some slight or other. There's nowhere near the push to compete that there once was, nor is there the funding (they used to pay for an entry from any writer who submitted one). This partly -- partly -- explains the Fort Worth Star Telegram's dominance these days.

In any event, with so many fields to recognize, no Katie winner gives an acceptance speech. If we did, we'd be there until next Christmas. Or until the liquor ran out. The awards ceremony is like a conveyor belt: A winner is announced and by the time he or she makes it up to the presenting stand, they've already named the next three or four.

I won the 2006 Katie Award for best arts criticism. My wife, Sara, noted that the News' report this morning makes me sound like "The Artist Formerly Known as an Employee of The News."

So if I could have, this is the speech I would have given:

"Before I say anything else, I must acknowledge my great good fortune in the editors I had at the Dallas Morning News. Diane Connolly, Bob Compton, Cheryl Chapman and Charles Ealy. I couldn't have accomplished half of what I did without you. Thank you.

But it says a great deal that not one of them is still there. As many of you may know, I'm no longer at the Morning News, either, having walked the plank and taken the severance package in September.

This is my fifth Katie Award. I don't mention that to brag but to indicate how special this one is, nonetheless. It's a small vindication, a small indication of the quality of talent the News shed two months ago -- writers such as Ed Bark, Dave Dillon, Kevin Blackistone, Scott Burns, photographers such as William Snyder. In this regard, I'd like to acknowledge my fellow former staffers among the finalists, including Pete Slover and Steve Steinberg -- people who walked away from the News with no job lined up, no paycheck, because they simply couldn't work there any more.

But I'd also like to commend those people who stayed -- for whatever reason. Many of you are trying to do quality journalism in a deeply demoralized atmosphere, working for a panicked, dithering management that has done little to address that demoralization and, in my own field, has trivialized cultural coverage with celebrity gossip, tiny blurb-reviews and generic wire reports. You have my sympathy.

All of this may sound bitter. But it's not because of the other reason this Katie is special: It may be my last. A part of the sense of relief that came with deciding to leave the News was the awareness that I could, if need be, leave daily journalism, too. I could quit show biz. So I'm leaving these battles to you. For now, I'm grateful to the Press Club and to the judges for giving me what may amount to a shiny bookend to my career in print journalism in Dallas. Thank you, and thank you, Sara, for making this possible."

With the new Casino Royale opening this weekend and with Simon Winder, author of The Man Who Saved Britain: A Personal Journey into the Disturbing World of James Bond making rather obvious declarations about how James Bond was Britain's replacement fantasy for its lost empire, I dug up my 10-year-old review of Andrew Lycett's biography of Ian Fleming. It's a book that many others, such as Christopher Hitchens, thought more highly of than I did:

A biography of Fleming -- Ian Fleming

by Jerome Weeks

April 28, 1996

To grasp Ian Fleming's achievement: Think of another pop novelist from the '50s whose work is still being made into big-budget movies, whose work is still an international commonplace.

It has been 42 years [now 52] since Casino Royale was released. Only Mickey Spillane's books could still be considered Hollywood properties, while Jim Thompson (The Grifters, The Getaway) is a late cult-contender. Other genre writers' works -- Harold Robbins', say -- have long since been ground into the wood pulp from whence they came.

In contrast, GoldenEye was a hit last year [1995]. The original 007 material petered out a decade ago, but Jurassic Park-like, GoldenEye has revived the dinosaur, and the most profitable movie franchise ever ($1 billion in box office) is hatching another film.

It's not outlandish to suggest that in 007 Mr. Fleming created a pop character nearly as universal as Sherlock Holmes -- another son of the British Empire. There's even the theory that our current genre of Bruce Willis-Arnold Schwarzenegger, massive-budget, action-boy films developed partly because the Bond series died out. A hole opened up in our collective movie psyche, and it promptly got plugged with Die Hard and True Lies.

All of which prompts the question, why? Why did we lap up this improbable stick figure, this piece of Tory voodoo? Bond waves his Walther PPK and his British bespoke tailoring and, magically, he's extricated himself (and the fate of the Western World) from all of these strange exploits.

Andrew Lycett's new biography, Ian Fleming: the Man Behind James Bond provides no answer, but then it never intends to. It's rather like Mr. Fleming's writing that way: highly readable, well-researched but somehow beside the point when it comes to evaluating James Bond.

Instead, we learn that Mr. Fleming didn't have the blue blood to qualify as Eurotrash. Granddad was a Scottish merchant banker -- hence, perhaps, Bond's penchant for up-market consumerism, as if flashing your designer-label socks made you sophisticated. Yet Mr. Fleming certainly did the Eurotrash thing in his early years, wandering the world as a promising young something-or-other with no visible career.

We also learn that Mr. Fleming was an amoral cad when it came to women, a bit of a sadist. He mistreated one girlfriend, she died in the Blitz and he felt guilty over it all -- prompting another woman to comment that you had to die before Ian felt anything for you. Ever diplomatic, Mr. Lycett doesn't note the high mortality rate among Bond's female conquests.

Perhaps the most telling thing that Mr. Lycett does discuss is Mr. Fleming's literary ambitions. He so wanted intellectual approval (much like his brother Peter's); his Hollywood success embarrassed him greatly. Those crass Yanks, they never get anything right. So -- can I freshen up your Boodle's?

Indeed, the films mutated Bond into some balloon-animal American: the gleaming gadgetry, the Playboy sexuality, the commando foreign policy, the cute Brits popping up like joke trolls. The film franchise itself became like a monstrous Fleming villain: moneyed, machine-oriented, decadent and with a hunger for global market share. What we always suspected is true: James Bond is Ernst Blofeld.

Mr. Fleming's increasing ambivalence toward his creation helps explain what John Cawelti and Bruce Rosenberg note in their fine analysis, The Spy Story: Mr. Fleming's writing is remarkably unstable; the dry, amused worldliness falls off often enough that you're not sure if he's actually spoofing himself.

What's more, it all got out of control, it all got tired. To be a free agent in a giant bureaucracy, to seduce and kill with aristocratic impunity: Sure, Bond's a modern fantasy, a formula. But Mr. Fleming had to believe in some of it. It's his real journalist's skill with authentic details that helps us swallow the sillier bits. When that fails, well, Bond just becomes Roger Moore in outer space. Or the films turn into GoldenEye, which tried so hard to be exotic, to be dangerous, it made you nostalgic for lazy but effortless junk like [the original] Ocean's Eleven.

In Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, his 1964 children's story that Mr. Lycett treats perfunctorily, Mr. Fleming created a magic car that could fly, swin and catch bad guys. Not unlike Bond, although the car, of course, had no license plate to kill. And in the end, in what's supposed to be an expression of free-spiritedness but now seems more like wistful impotence, the magic car flies away, out of control, no one knows where.

copyright, The Dallas Morning News

Addendum: I must add that the new Casino Royale is easily the best Bond film in years, perhaps, yes, the best ever. Rather than trying, once again, to find a guy who looks great in a tuxedo and then have him pretend to be a killer, they found a fine actor -- Daniel Craig, the British Steve McQueen -- who can make us believe he's a cold-blooded killer but who, as one character puts it, wears his expensively-cut suits with disdain. It's what Timothy Dalton tried to do when he was Bond -- a seriously underrated Bond, I believe -- but his 007 vehicles turned out be underpowered.

And then, perhaps, the smartest thing the Casino Royale creators do is that they give this Bond a heart. Which means there's something at stake beyond the usual global domination/nuclear warhead/terrorist plot.

It's still a formula; but this Casino Royale shows why the formula once worked.

Time and Publishers Weekly have broken the embargo on reviewing Thomas Pynchon's new novel, Against the Day. Much excitement and fascination ensues. PW gives it a starred review ("Knotty, punchy, nutty, raunchy"), Time hyperventilates at length.

Sorry, I'm going to bed. Maybe it's a great book. But I gave up on Mr. Pynchon round about Vineland, then tried again, only to endure the unbearable slog that was Mason & Dixon. Cartoony characters with punning names. Prose that grates, soars, rambles, bores. Clanking stories contrived to demonstrate a thesis. Or as Richard Lacayo rhapsodizes in Time: "the tantalizing music of Pynchon's voice, with its shifts from comic shtick to heartbroken threnody, its mordant Faulkneresque interludes, its gusts of lyric melancholy blown in by way of F. Scott Fitzgerald, its ecstatic perorations from Jack Kerouac. . . ."

. . . as well as his inability to leave out any joke (the dog's name is LED!!!), his willingness to fracture narrative or emotional sense for some abstruse scientific-philosophical point: The list goes on.

His best work remains The Crying of Lot 49. There's something to be said for the elegance of succinctness.

Coincidentally enough, while news media were pondering the death of East German spymaster Markus Wolf and the 50th anniversary of the Hungarian uprising -- when the Cold War turned uncomfortably hot -- I happened to be catching up on a number of espionage novels I'd passed by in recent years.

They caused me to see general patterns in the Cold War spy novels, patterns that continue even today. The best spy thrillers, it seems, have told three central stories:

The story of betrayal. This usually but not necessarily involves double agents revealing secrets of the West to the Soviet Union. It can also concern an American or British spy's moral dilemma in deceiving the people he knows in the 'host' country or how the political/military needs of the West lead him to support then betray our third-party allies.

The story of brutalization. These novels track how the spy game makes Western agents become as harsh or duplicitous as the Communist enemy, undermining the very democratic principles we're supposed to be championing.

Or the story of sacrifice. In order to win the espionage game -- or just play it -- the good guys often find they have to give up things (see above, the brutalization). But this tale can be the story of a futile sacrifice. Or a heroic one. Obviously, all three of these stories are often related, nestled inside each other.

It seems to me that these are the abiding moral concerns of the finest modern spy thrillers: These books would include (but aren't limited to) the best of Graham Greene, early Len Deighton, early-to-mid John le Carre, a couple of Alan Furst's. All other basic narratives in espionage novels are more or less dressed-up variants of James Bond derring-do: how we trumped our dastardly foe through pluck, superior gizmos and dashed cleverness. That's not to say such tales aren't fun to read; but they're not exactly in the business of seriously considering and/or questioning the espionage enterprise.

All of this came to me while catching up with the heralded spy novelist, Robert Littell, whose work I hadn't read since I'd enjoyed his The Defection of A. J. Lewinter as a teenager in 1973. Since then, he has produced a number of books, notably Legends (2005) and The Company (2002), that have been hailed as masterpieces of the genre. In particular, The Company has been called America's answer to John le Carre's broodings on the classic Cambridge spy ring (Philby-Burgess-Maclean).

Well, no, it isn't, not really. Both books are disappointing insofar as Mr. Littell's characters are mostly cardboard and his style mostly serviceable when not outright clunky. Serves me right for granting any credence to a blurb by Tom Clancy, a dreadful author whom I once heard sagely tell a rapt audience that Samuel Johnson "invented the dictionary" (yes, Clancy said that, no, Johnson didn't invent it).

Legends is stranger, more convoluted but more easily dismissed. It's an improbable variation on Robert Ludlum's The Bourne Identity. In that book, Jason Bourne suffers amnesia, and while people try to kill him, he slowly discovers that he was a professional spook-assassin -- and that his employer and his former target are both after him.

In Legends, old CIA hand Martin Odum must struggle with three fabricated identities -- his "legends." He can no longer recall which one is his real life. Like Bourne, he tries to dig up the truth with the help of a lovely woman, while various people try to kill him. If the reader can't figure out who Martin is, what caused his memory loss and who's after him, the reader is not trying very hard. I'm not a whiz at deciphering such things, but it seemed plain to me. What's more, it didn't seem particularly interesting or credible; I was mostly just curious to see how Mr. Littell would work it out. Yes, spy thrillers are fantasies, but the best exist in a tension between realism (espionage is an awful business) and make-believe (a heroic individual armed with an atomic tie clip -- yes, you there -- can defeat whole armies). Legends does have a hall-of-mirrors or it's-all-in-his-head quality that lends it a weirdly insubstantial feel, but this only makes its convolutions seems all the more unhinged from reality.

In fact, rather than Cold War tales, both Bourne and Legends really belong to the subset of 'rogue CIA operations' with the villain being, not so much the Communists, but our own CIA supervisors. In short, Legends is a late, baroque product of the Watergate and Church commission era.

The Company, on the other hand, is much more ambitious in the epic manner. It's a fictional history of the agency -- all the way from Truman's founding directive and the early days in Berlin through the Hungarian fiasco, the Philby fiasco, the Bay of Pigs fiasco, the 'Operation Mongoose' fiasco and so on, right up to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It's a multi-generational saga, with the children of the first wave of true-believing agents picking up the banner in the '60s and '70s and with real-life figures (the paranoid counterespionage chief James Jesus Angleton) interacting with the fictional spies.

An epic novel tends to develop character over long stretches of time. So they may seem like only stereotypes or outlines at the beginning, but they fill in over the long haul, they change, they deepen. But not here. With the notable exceptions of Angleton and the corpulent, alcoholic but wily Berlin chief Torriti (aka "the Sorcerer"), the American agens are all true blue go-getters until they encounter betrayal or overreaching disaster, as in Hungary and the Bay of Pigs. Then they turn bitter in identical and non-distinguishing ways.

The Soviets, in contrast, are run by a nefarious genius (Starik -- "old man" in Russian) who is, of course, a pedophile and remains a pedophile. I have little doubt that in the Cold War, the Soviets were the bad guys for the most part, but I suspect they were bad guys not because individually they were pervs. This is pretty much the extent of Mr. Littell's moral complexity. We turn sour from our dirty and often incompetent dealings (although some of us manfully press on); they were sickos from the start.

Mr. Littell's research is awe-inspiring. He produces almost molecular details about every location, every piece of tradecraft. But background research does not constitute a novel, and when he does write about something the reader might be familiar with, it can feel pointless, so much flotsam. In the early '50s, two young characters fall in love and are delighted to find they share the same favorite novel. That novel? Catcher in the Rye. This is akin to saying two lovers like Seinfeld. It's such a commonplace, it tells us next to nothing about them as individuals. It's characteristic of Mr. Littell's writing that in all the intertwining plots, one frequently can't tell the fathers from the sons, long-time friend from long-time friend, and the reader has to flip back to determine, again, just which cookie-cutter character he's currently following.

Because of all his historical research and because The Company spans some 40 years, Mr. Littell often has to lay so much pipe (translation: stuff in exposition), the reader is burdened with sentences such as the following. They both have take-a-deep-breath structures, but my favorite is the second -- its subject nearly expires by the time the verb appears:

"Bissell, a tall, lean, active-volcano of a man who had replaced the ailing Wiz as Deputy Director of Operations, loped back and forth along the rut he'd worn in the government-issue carpeting, his hands clasped behind his back, his shoulders stooped and bent into the autumn cat's-paw ruffling through the open windows of the corner room. Hunt, a dapper man who had been assigned to kick ass down in Miami until the 700-odd anti-Castro splinter groups came up with what, on paper at least, could credibly pass for a government in exile, kept his head bobbing in eager agreement."

Next time: three current books about undercover doings that are definitely worth a look.

The report in The New York Times today that brilliant Australian scientists have invented a t-shirt that acts as a guitar has inspired me to pull another quotation from Dave Hickey's essay collection, Air Guitar:

In "The Little Church of Perry Mason," Mr. Hickey hilariously, ingeniously and quite seriously argues for the cultural significance of the classic TV show based on Earle Stanley Gardner's defense attorney. But immediately after grad school, Mr. Hickey strayed:

"For a year or so, I was helplessly addicted to Mission Impossible, which I quickly recognized as the Church of the Small Business Guy because for one hour, every week, there was a task to be performed, and by God it was! If you needed expertise, you sent out for the best people -- and they all showed up! Right on time, and they didn't hate one another, or call in sick, or show up stoned, or complain about the bucks, or loaf on the job. They were fucking professionals, who could operate the equipment -- and the equipment, my friend, always worked!"

Meta-fiction -- "an umbrella term for works that are self-conscious and self-curious, and includes non-linear exercises in structural experimentation" -- is showing at a movie theater near you, says Duane Dudek.  Charlie Kauffman's scripts, Michael Gondry's movies, and now Babel and Stranger than Fiction.

Charlie Kauffman's scripts, Michael Gondry's movies, and now Babel and Stranger than Fiction.

Mr. Dudek quickly admits that "meta-fiction is probably as old as self-awareness." Indeed, despite the conventional wisdom that the novel was born as a realistic, 18th century product of the rising middle class, a case can be made that its first great work was that classic meta-masterpiece, Don Quixote.

And as for films, there's always Buster Keaton in the wonderful Sherlock, Jr (1924) -- in which as a movie projectionist, he dreams himself into the film onscreen.

In England, one quickly learns -- as I did one summer hitchhiking and BritRailing around the country -- how much larger World War I looms in British memory than Word War II -- "our" war. Every town has its WW I memorial with a list of the dead, often hundreds of names from a little country town.

The "lost generation."

My grandfather fought in WW I as a Browning automatic rifleman -- but I never heard that taciturn man speak of it. Simon Crump never heard his grandfather speak of his service in WW I, either, but he watched him flinch at firecrackers and grimace at bonfires. Every autumn, Mr. Crump reads a book about WW I, and this year, he picked Frederick Manning's The Middle Parts of Fortune (originally called Her Privates We). It's a remarkable novel for its simplicity -- not its crudity or naivete but for the unwavering directness and clarity of Manning's account of the Battle of the Somme. Crump captures it well; Ernest Hemingway called it the "finest and noblest" book on men at war he'd ever read, curiously falling into precisely the kind of shining language he (and Manning) normally avoided.

Pehaps because of the (deserved) attention given the death of Ed Bradley, I hadn't noticed that my favorite radical feminist rock critic, Ellen Willis, has died. I was stunned. Some of her writing in the Village Voice in the '70s and '80s shaped my own thinking about pop culture, politics and sexuality. I didn't agree with some things she wrote -- her statement that "good writing is counterrevolutionary" is astonishingly wrong-headed (just ask Flaubert). But her stand against anti-porn feminists (while advocating a "new feminist pornography"), her unashamedly "difficult" thinking about pop music, her ability to re-state, re-think and re-frame political debates-- notably democratic secularism vs. religious freedom -- and her withering wit when it came to defending the independence of women (on issues from abortion rights to consumerism) were inspiring, to say the least. She was fearless, it seemed, yet compassionate.

A few favorite, quickly culled lines indicative of her depth and range:

"[David Boaz, of the right-wing/libertarian Cato Institute] complains of unmarried welfare mothers' 'long-term dependency' on government, as if it were unquestionably preferable that mothers be forced into long-term dependency on husbands."

"There are two kinds of sex, classical and baroque. Classical sex is romantic, profound, serious, emotional, moral, mysterious, spontaneous, abandoned, focused on a particular person, and stereotypically feminine. Baroque sex is pop, playful, funny, experimental, conscious, deliberate, amoral, anonymous, focused on sensation for sensation's sake, and stereotypically masculine. The classical mentality taken to an extreme is sentimental and finally puritanical; the baroque mentality taken to an extreme is pornographic and finally obscene. Ideally, a sexual relation ought to create a satisfying tension between the two modes (a baroque idea, particularly if the tension is ironic) or else blend them so well that the distinction disappears (a classical aspiration)."

"The devout cannot have it both ways. Pro-church arguments have made headway on the left by purporting to defend the democratic rights of the religious, but this is not really a debate about rights. Rather, what pro-church militants are demanding is exemption from challenge to, or even criticism of, their claim to a privileged role in shaping social values. With no sense of contradiction, they presume the right, even the obligation, to attack secularists' worldview while feeling entitled to unquestioned "respect," which is to say suffocating reverence, for their own beliefs. In a democracy, however, organized religion has no more right to be shielded from opposition than the state, the corporation, the labor union, the university, the media or any other institution."

"My deepest impulses are optimistic, an attitude that seems to me as spiritually necessary and proper as it is intellectually suspect."

Perhaps the most incisive observation made by New Yorker journalist-author Lawrence Wright (The Looming Tower) in his memoir of growing up in Dallas, In the New World, was how oddly flattening it was, living in a place left mostly unexamined by great artists.

It partly was what prompted his memoir, Mr. Wright said -- which remains one of the more thoughtful books written about the city. When great authors write about your town, you see things about it you might never have on your own. You are given new understandings. I agree. Garry Wills' single line about Dallas in his biography of Jack Ruby -- "Dallas has always been a city on the make" -- has stuck with me, a perfectly phrased, telling insight. Mr. Wright looked around, and outside of the deluge of books about the Kennedy assassination, found very little of real depth written about Dallas. There are a handful of good or oddball novels about Dallas (Bryan Woolley's November 22, Edwin Shrake's Strange Peaches) but only one truly remarkable one, I'd argue, one that's likely to last: Don DeLillo's Libra, and it's not really "about" Dallas at all.

But there's something to be said about the other side: how the magnetic field of a great author bends everyone to his vision, how his books blind people to everything else about your hometown, particularly when they're made popular and commercial by Hollywood and tourism. Sarah Burnett grew up in Dorset -- "Thomas Hardy country" -- and writes for the Guardian that it was Hardy-Hardy-Hardy all the time:

"The pleasure was decidedly short-lived. Indeed, it very quickly turned to pain. ...

Under the Greenwood Tree, Far From the Madding Crowd, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Tess of the D'Urbevilles, Jude the Obscure - we read them all in the space of a year or two, each book more gloomy than the one before, the fatalism piling up chapter by chapter. You'll never escape from here, there's no point in trying, you're all doomed ... Just as Hardy finished half of the chapters in Tess with the words 'If only she'd not ...', most of us left our English classes thinking 'If only we'd not been born here ...' "

"[Criticism] neither saves the things we love (as we would wish them saved) nor ruins the things we hate. Edinburgh Review could not destroy John Keats, nor Diderot Boucher, nor Ruskin Whistler; and I like that about it. It's a loser's game, and everybody knows it. Even ordinary citizens, when they discover you're a critic, respond as they would to a mortuary cosmetician -- vaguely repelled by what you do yet infinitely curious as to how you came to be doing it. So when asked, I always confess that I am an art critic today because, as a very young person, I set out to become a writer -- and did so with a profoundly defective idea of what writing does and what it entails."

"[Criticism] neither saves the things we love (as we would wish them saved) nor ruins the things we hate. Edinburgh Review could not destroy John Keats, nor Diderot Boucher, nor Ruskin Whistler; and I like that about it. It's a loser's game, and everybody knows it. Even ordinary citizens, when they discover you're a critic, respond as they would to a mortuary cosmetician -- vaguely repelled by what you do yet infinitely curious as to how you came to be doing it. So when asked, I always confess that I am an art critic today because, as a very young person, I set out to become a writer -- and did so with a profoundly defective idea of what writing does and what it entails."

-- from "Air Guitar" by Dave Hickey.

Mr. Hickey's recent appearance in the pages of Harper's inspired me to re-read several favorite essays in Air Guitar. This is the first in what will probably be a series of quotations from those essays.

Diane Johnson in the New York Review of Books has joined the throngs who love Nora Ephron's I Feel Bad About My Neck -- leaving me one of the few critics who found the book disappointing, trivial compared to her best, pioneering work in Crazy Salad and Wallflower at the Orgy. You can read my Aug. 27 review for The Dallas Morning News here.

But my friend Sarah Bird -- author of The Flamenco Academy -- has written one of her best columns for Texas Monthly in response to I Feel Bad About My Neck. A splendid piece that sets Ms. Ephron's kvetching about wrinkles against the gutsiness of Real Texas Women like the late Gov. Ann Richards:

"I was still puzzling over this question [why Nora was so obsessed with wearing black turtlenecks to hide her neck] when the news came that Ann Richards had died. Like the rest of the state and the nation, I could not stop staring at those piercing turquoise eyes, that white tornado of hair, the blinding grin. But mostly I studied her glorious and gloriously exposed collection of shar-pei-quality neck wrinkles. And then it hit me: Real Texas Women don't wear black turtlenecks. If neck wrinkles bothered a Real Texas Woman as much as they bother Nora and her bescarfed friends, she'd go out and find the best plastic surgeon around, have the damn lift, and throw a party to show it off. Or she'd get herself something a lot bigger to worry about, like taming a frontier or being governor or becoming one of the greatest female singers in the history of rock and roll. (Janis Joplin, you freed more women from undergarments and hair straightener than you will ever know.)"

Brava, Sarah. Read the whole thing here You may have to register; this month's password is "uvalde." Enjoy.

Jonathan Littell, the son of spy novelist Robert Littell (Company, Legends) has won France's Goncourt Prize with his 900-page novel, Les Bienveillantes (The Kindly Ones), a novel narrated by a Nazi officer. Something of a success de scandale in France, it won't be released in America -- get this -- until 2008.

No one is saying this so far, in the reports I've read, but he seems to be the first American to win the Goncourt.

This site doesn't normally link to The New York Times because I figure you folks are literate, most of you have already been there, read that. But the cover essay/review in yesterday's Book Review by Michael Kinsley was exceptional. And I'm not a fan of Mr. Kinsley. But in writing about a clutch of political books bemoaning what is wrong with our current Republican dominance, the state of elections, the Democrats' dithering, Mr. Kinsley ducks through the usual crossfire to get to some basic fears about how this republic is running things, fears that go well beyond who wins tomorrow. He's also unafraid to re-visit the nasty question of how the 2000 election played out. Recommended.

"If you really get down to the disaster, the slightest eloquence becomes unbearable."

-- Samuel Beckett

This year is his 100th anniversary, and Charles McNulty does a good job rounding up what's going on, from LA to Dublin. Unlike the New York theater critics at the time, McNulty dismisses Mike Nichols' dreadful, celebrity-stuffed Godot for Lincoln Center in 1988. About the only person to come out of that with his dignity intact was Bill Irwin as Lucky.

But best of all, because UCLA Live's Theatre Festival is presenting staged excerpts, the great trilogy of novels doesn't get short shrift, as is often the case:

"Reading Beckett today continues to be exhilarating. The tensile strength of his staccato sentences, the idiomatic hilarity (particularly pungent in the English translations he prepared or carefully oversaw of his more muted French prose) and the ironic debunking of literary and religious quotations are just a few of the pleasures he offers.

But the challenge of his writing has only grown in an age in which expediency has become the highest virtue. One can't plow through "Molloy" and the others the way one can a batch of Ian McEwan novels. Beckett requires an almost Zen-like attention to the moment. With the Internet cultivating a new generation of attention-deficit readers, the level of concentration it takes to wend down an associative stream (as opposed to steamrolling down a narrative superhighway) may be beyond what most of us are prepared to give."

Unlike most American reviewers, it seems, I found Jane Smiley's 13 Ways of Looking at the Novel so irritating I couldn't review it. I didn't know where to start my rant. Her pompous tone. The blithe disregard of Beckett's novels. Her references to her own works as perfect models.

Happily, Sophie Ratcliffe managed to control herself, as the British are wont to do, just enough to rip into it, although just barely: "One is tempted to throw something. Perhaps a copy of the former bus driver Magnus Mills's Booker Prize-shortlisted novel The Restraint of Beasts. The snobbery of this passage nearly disguises the fact that it doesn't make sense. "

Thanks to J.D. for the link.

It seems we're still debating just what the Black Death was, although given its effects on human history, it may have been our closest experience to annihilation. Estimates range as high as 60 percent of Europe died; whole towns were emptied. And that doesn't count the dead in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. Some of the most moving personal accounts can be found in medieval manuscripts -- which stop with the author's last prayer. "Videtur quod Auctor hic obiit" one copyist noted: "It seems the author died here."

But if you really want to know how it operated, Ole J. Benedictow's book, The Black Death: 1346-1353, The Complete History seems to be the place to start. The book, released in February, is reviewed in the TLS and the controversies (whether it was the bubonic plague or a virus, which rat was responsible) are explained with the kind of detail one can really feel: "The blockage in its stomach prevents the maddened, dying flea from being able to ingest more than a small amount of human blood, and causes it instead to regurgitate tiny amounts of infected rat blood . . . "

A feminist update on my list of favorite thrillers: book/daddy will not be a site (entirely) dedicated to thrillers, but there was a strong response to my first postings, which just happened to consider noir novels.

In particular, many readers sent their recommendations for hard-boiled female author/heroines because my 'top 10 favorite literary thrillers' (which, of course, listed 15 books) didn't include a woman. But I consciously addressed that lack, noting that even Patricia Highsmith, one of the few acknowledged female masters of the hard-boiled school, created a male protagonist. I expressed a willingness to consider a female heroine; I just hadn't found one.

In particular, many readers sent their recommendations for hard-boiled female author/heroines because my 'top 10 favorite literary thrillers' (which, of course, listed 15 books) didn't include a woman. But I consciously addressed that lack, noting that even Patricia Highsmith, one of the few acknowledged female masters of the hard-boiled school, created a male protagonist. I expressed a willingness to consider a female heroine; I just hadn't found one.

That opened the floodgates. Even Laura Lippman, author of the Baltimore-based Tess Monaghan novels such as Charm City and Butchers Hill, weighed in with a thoughtful, personal e-mail, dismayed at the gender bias of another all-male hard-boiled list. (For the record, she does not consider her novels hard-boiled -- she wasn't arguing for herself as a candidate.)

I'm grateful to the many readers who wrote because the top vote-getter was Denise Mina, specifically her 2005 novel, Field of Blood (recently released in paperback). I read it over the weekend, while at the Texas Book Festival. I quickly remembered why I'd not picked up the novel when first released: Some of the hosannas greeting it compared Ms. Mina enthusiastically to Patricia Cornwell, an overrated author whose work, I am thankful, actually isn't much like Field of Blood at all. That title, also, suggested a bad Ann Rice gothic tale (I still think the title is misleading).

But I was mightily impressed. Field of Blood is very good. The evocation of Glaswegian gloom and class/religious resentments, the portrayal of bottle-of-booze-in-the-bottom-drawer, old-style newspaper journalism, the fading Irish Catholicism of Paddy Meehan, the novel's young, female "copy boy," and her struggles with her family and her boyfriend -- good stuff, well done, all of it.

But I'm still not adding it to my list. To learn why, you'll have to continue past the SPOILER ALERT my reasons can spoil the story for those who haven't read it.

If, like me, you would be curious about what happened to everyone behind the irreverently influential SPY magazine, The New York Times provides a helpful, hard-to-read, SPY-like chart in its print version today. And not online -- I keep pointing out articles that aren't online; it's just coincidental so far, but it tells you about what I read.

It so happens I own every issue of SPY magazine ever printed from 1986 to 1998, yes, even the later, sadder, lousier ones, long after Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter had sold the thing. OK, I own all except one, June 1987, if anyone has a copy and is interested in selling it, please contact me. I'm not a collector; I'm not sentimental about stuff. Obviously, I do have a lot of books, but I regularly cull them to try to keep them from conquering the world.

It so happens I own every issue of SPY magazine ever printed from 1986 to 1998, yes, even the later, sadder, lousier ones, long after Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter had sold the thing. OK, I own all except one, June 1987, if anyone has a copy and is interested in selling it, please contact me. I'm not a collector; I'm not sentimental about stuff. Obviously, I do have a lot of books, but I regularly cull them to try to keep them from conquering the world.

But SPY was different. Now that a SPY retrospective has come out -- SPY: The Funny Years -- there has been the requisite praise and chatter about how the magazine anticipated David Foster Wallace's fascination with footnotes, how it started a revolution in print design with all of its tiny type and charts and doohickies and, above all, most importantly, how it was the precursor to All Things Snarky on the web. For those of us who find the relentless bitchiness at Defamer or Gawker thin and tiresome after a short while, this last is not exactly a compliment.

That's because, with a variety of editors and writers, including non-bitter humorists such as Roy Blount, Jr., Ellis Weiner and Vince Passaro (novelist: Violence, Nudity, Adult Content),Spy was not simply a list of sniper targets. In fact, in its early years, it was often called "The New Yorker with bite" (the cover even used to say "The New York Monthly"), and it had a high degree of Manhattan-centric whimsy about it. It was only in the '90s that it became known as the anti-Vanity Fair, the publication that, instead of enshrining celebrities as Bruce Weber-photographed gods and goddesses, cheerfully brought them down a few pegs.

Even so, it was too sophisticated, too rich, to be reducible to mere snark -- until, yes, its later years. For those who don't know anything about what I'm talking about, you need to crack open the new anthology, although I should warn you that in the highest traditions of SPY, it's a handsomely done production with far too much type that is almost impossible to read. For those who do know what SPY was about, you'll agree, I think, that it was a finer, more intelligent humor magazine than National Lampoon and certainly deserves the anniversary look-back appreciation, no matter how predictably shabby and media-driven the cash-in motivations might be.

Snark.

But I'm serious about that June '87 issue. Contact me.

The wonderful British novelist-playwright-essayist Michael Frayn (Copenhagen, Noises Off) takes on Immanuel Kant in his new book, The Human Touch: Our Part in the Creation of the Universe (already out in England, not out here until January). And thanks to reviewer Nicholas Blincoe you might be able to understand anthropocentric piggy-in-the-middleness.

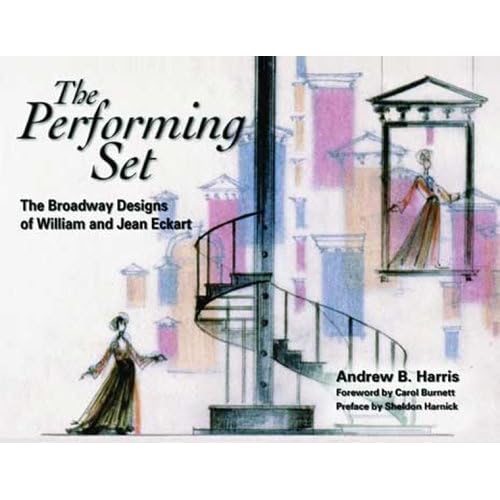

... to give myself (and a friend) a pat on the back. Word comes from Andrew Harris that his book, The Performing Set: The Broadway Designs of William and Jean Eckart is a finalist for the USITT's Golden Pen Award. That's the United States Institute of Theater Technology, and the award is for an outstanding book in the field of production and stage design.

Bill and Jean Eckart were the gold standard for set, costume and lighting design in the heyday of the Broadway musical: They designed Damn Yankees, Once Upon a Matress and Mame, for starters. In the '50s, the exultant image of Gwen Verdon as the devilish Lola in Damn Yankees with her hands on her hips in her black high-cut lingerie was arguably as electrically sexual as the Marilyn Monroe airlift skirt shot, part of the period's taboo-testing and certainly the most famous theater costume of the era. It once towered over Broadway on a billboard, became the icon of the newspaper ads and the subsequent film. Don't take my word: Read Frank Rich's personal erotic encounter with Lola in his memoir, Ghost Light.

Jean Eckart designed that outfit. The Eckarts, who lived in Dallas and taught at Southern Methodist University, approached me about writing the book, I started it, realized I wouldn't be able to complete it and Andy took it over. I'm glad he did; he did a better job than I could in mining the archives and interviewing the survivors, including Carol Burnett. Regardless of all that and of Andy's sensitive analysis of the Eckarts' methods and aesthetics, the book is simply lovely, with some 500 color illustrations, many of them the Eckarts' personal watercolors and sketches. Anyone interested in the Golden Age of Broadway will want to take a look at The Performing Set

The best among the USITT finalists will be chosen and announced in March.