Money for Art, Pt. 2: Replaying the '50s and '90s

Justine Smith, Absolute Power, dollar bills, 2005

Money for Art, Pt 1: Arts Funding in America

David A. Smith's Money for Art: The Tangled Web of Art and Politics in American Democracy recounts the history of federal funding of the arts since 1817 when Congress bought its first set of oil paintings. But Dr. Smith -- a senior lecturer in history at Baylor University -- mostly gets through the decades up to the 1960s to set up his account of the National Endowment for the Arts, which is more or less the heart of the book. Indeed, it's possible to read Money for Art as an extended preamble to the NEA's culture wars in the '80s and '90s. The book is an attempt to explain that outbreak by putting it in a historical context -- to explain it, learn from it and perhaps even get past it.

Dr. Smith believes that since the '60s, the NEA -- and American culture in general -- has gone too far in valuing (even celebrating) the needs and impulses of the individual artist. Built up over the course of several chapters, Dr. Smith's argument is that by the '80s, the arts and the NEA had become estranged from much of the American public (and its political leaders). They had discredited themselves in the eyes of many by becoming over-intellectualized, over-concerned with 'transgression' and 'revolution' for transgression and revolution's sake. The NEA was increasingly beholden to a small, insular set of art-world postures and lefty academic opinions. It had embraced a multi-cultural pluralism, thereby surrendering whatever authoritative judgments the endowment made on the artworks it chose to fund.

A backlash from taxpayers and political leaders was bound to happen.

A good case can be made for some of this. Some of it -- no. To take one example: Citing Tom Wolfe's The Painted Word, Dr. Smith presents the idea that the arts have become increasingly esoteric, obsessed with critical theory and have deliberately dismissed a middle-class audience's understanding.

Undoubtedly, some have. But there are two chief weaknesses with this

view. First, as Dr. Smith more or less recognizes, it applies a

situation in the visual arts to all the others. In fact, Money for Art

is often limited by Dr. Smith's reliance on building his case through

the visual arts. Although he makes reference to the other arts, the

great majority of his evidence, his thinking, his history, is derived

from painting and photography.

American theater, for example, doesn't really follow this supposed pattern of "increasingly obscure works deliberately alienating middle-class understanding or acceptance." Outside of the occasional, surrealist exception like Suzan-Lori Parks or Sam Shepard, our leading dramatists -- Eugene O'Neill, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, David Mamet, Tony Kusher, Wallace Shawn and so on -- have all worked within the general conventions of stage realism. These playwrights may aggressively question aspects of American culture, but Shakespeare or Shaw would have little trouble following their scripts. Much the same could be said for the contemporary novel. For every difficult experimentalist or fabulist on the order of Don DeLillo, Kathy Acker or David Foster Wallace, there have been dozens of Richard Fords, Mary Gordons, John Irvings, Russell Banks, Grace Paleys, Joyce Carol Oates and so on.

Second, Dr. Smith's view presupposes as a universal ideal the aesthetics and accessibility that culminated in 18th-to-19th century Western realism. A landscape is a landscape, a still life is a still life, a portrait is a portrait, and it didn't require specialized study to grasp the subject of a painting -- from the 19th century all the way back to the Renaissance. Nor was a viewer likely to feel threatened or disoriented by an artwork. It's only when abstract art and cubism and Dadaism (and explicit left-wing ideology) enter the field in the late-19th-early-20th century that the separation between artist and audience supposedly begins. And it really becomes a divorce with abstract expressionism, conceptual art, minimalism, post-modernism, performance art, assemblage, neo-conceptualism and so on.

But this standard of 'accessible, conventional realism' holds true only for a portion of art history and only for a portion of the art works created during that period. I defy anyone -- without some specialized study -- to decipher the many minor Greek deities and nymphs, the obscure saints and historical references, the Christian allegories and Old Testament figures that swarm through Western art up through 19th-century neo-classicism. Set aside something as involved and crowded with figures as, say, Michelangelo's Last Judgment or the torrents of mythology and royalty in Rubens' works. Let's take a simpler-seeming work. Who were the Horatii in Jacques-Louis David's Oath of the Horatii? Did you know before you ever saw the painting? Yet we need to know who they are in order to understand this dramatic moment.

For centuries, artists served a narrow, highly educated audience. The idea that a painting should be immediately appreciated by all of us middle-class sorts only developed after there was an audience made up of all of us middle-class sorts willing to buy it. Dr. Smith does back off from the overtly polemical bent of Wolfe's attack against the lefty thinking embedded in some modern art. Dr. Smith notes that, to a degree, all art is "aristocratic." It is created by people with unique talents and a unique vision that may not be embraced by the mainstream. He might have added that this is often because the art work in question presents a critique of the mainstream. This doesn't mean that appalling the majority of ordinary people is a sign of great art, only an occasional consequence of some great art.

Our feeling alienated by art is not a facetious point but neither is it a recent phenomenon. Popular support for the Bonfire of the Vanities -- the 1497 burning of hundreds of artworks and luxury items that was ordered by the Dominican friar Savonarola -- was partly motivated by ignorance, by the widespread suspicion that all of these paintings and sculptures of gods and goddesses were not celebrations of classical antiquity but simply pagan immorality. Dozens of masterpieces by artists like Sandro Botticelli were burned because the Italian Renaissance was an aristocratic affair; thousands of ordinary, untutored Italians didn't appreciate neo-Platonic theory.

Roland Bernier, Red Money #3So today, many artworks bewilder or challenge us. I would argue that this has often been the case. Even so, for several decades now, there have been various art movements pushing for simplicity or a lack of irony or a lack of in-your-face transgression, movements extolling a return to 19th century realism in novels, melodicism in classical music and the figurative in painting and sculpture. They've been around long enough already that in some instances, they're cliches. Noted art critic Dave Hickey once stated that beauty "remains a potent instrument for change in this civilization." Simply as an agency of visual pleasure and not of education or spiritual improvement, beauty, he said, would return as a central concern for art. Hickey made this now-famous declaration 16 years ago.

Dr. Smith's point would be that there's nothing wrong with art that is challenging or bewildering until we ask a democratic government to justify funding all that challenging, bewildering art. In any prolonged, public argument over restricting the content of funded art (which is what the '90s culture war essentially was), artists and arts supporters will lose. There are far more people bothered or bewildered by their work (or uncaring of it) than there are admirers of it. Even with mass media and mass education -- some might say because of them -- the audience for challenging, difficult art work is still, relatively speaking, small.

What's more, Dr. Smith insists, such wars over artistic content run against the original purpose of the NEA -- which was, in effect, to unify and uplift us through art, not bedevil or anger us. Yes, uplifting the viewer is a constricting and old-fashioned notion of art's purpose. Julian Barnes in Flaubert's Parrot notes that all of this talk of "uplift" in art makes it sound like a brassiere. But as Barnes also notes, "brassiere" is the French word for "life jacket." These days, art may not don something as highfalutin' as the mantle of truth, but it still may save us.

Actually, when one considers Dr. Smith's account of the origins of the NEA, it's plain that the endowment was established not with a single goal but with all sorts of conflicting ideals in mind. Even so, he's right. Insofar as convincing Congress that arts patronage is worth the trouble, 'uplift and unify" are the sales pitches that work. (That, and making sure, as many government agencies do, to spread the grants around to key Congressional districts.)

In all this, I think Dr. Smith -- as do many others -- understandably pines for the old middlebrow consensus. The term middlebrow is not a pejorative here. From the '20s to the '70s, there was a widespread belief that highbrow arts like classical music and serious literature were good for us ("uplift and unify"). These same arts could also be made palatable for the great many of us who typically didn't follow them. And these same arts could even find a welcome spot in the mass media.

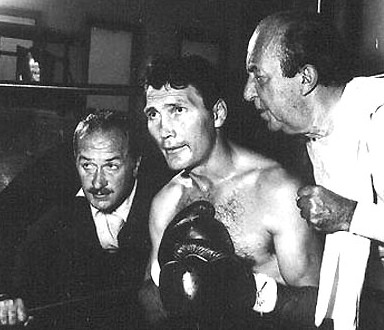

What resulted has often been called a "golden age" for classical music, live theater and other arts -- considering their relatively prominent presence in American culture and the American home. The mid-'50s to mid-'60s was the heyday of the Book-of-the-Month Club, Leonard Bernstein's Young People's Concerts on CBS, Playhouse 90 and Actors Studio presenting TV dramas written by Paddy Chayefsky, Horton Foote, Gore Vidal and Rod Serling (that's his Requiem for a Heavyweight, pictured below) This was the era when Salvador Dali appeared on TV's What's My Line?, when Van Cliburn became a national hero for winning the Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in Moscow.

But all these cultural currents came together during the mid-'50s-to-mid-'60s partly because of large-scale social forces -- like the Cold War, like the GI Bill. Millions of Americans went to college for the first time, often as the first person in their family to do so. They were exposed to these arts often for the first time -- or they were educated to appreciate them for the first time. To all of these college-educated Americans, we must add their immigrant parents -- with their faith in education -- and we get a middle-class that was eager to shed any Babbitt-ish self-image (or ghetto-ish 'foreigner' image), a middle class that believed deeply in education not just to get ahead but in the idea of the educated, cultured person as a worthy role to aspire to. What's more, those immigrant parents still held dear many of the traditional European arts: the symphony, the stage drama, the large-scale novel of earnest, social concern. They conveyed their beliefs in the arts as enlightening, as social betterments, to their children.

Whether all of this was naive or culturally narrow-minded is not the point. Bring all of these currents together and we have what may have been a unique cultural moment, a moment that led directly to the establishment of the NEA. And it was the same precise moment that saw all hell break loose in the arts, in politics, in popular culture -- eventually dooming that "middlebrow consensus." Dr. Smith recognizes this, noting the irony that the NEA was seeking to promote the arts as unifying and uplifting just when they fragmented and shed any claim to universal truth or beauty.

But it wasn't simply those radical artists who brought this upon us and themselves. Huge changes in the popular entertainment industry -- like the rise of rock 'n' roll, like the TV networks dumping all their high-culture programming -- played a major role as well. As did anti-war politics, as did civil rights, which saw middle-class, middlebrow culture lose much of its authority. Then came the onslaught of the electronic media, which only increased the fragmentation, first cable television and then, of course, the thing you're looking at now.

All of this history is relevant to Money for Art because, one, you can't put the genie back in the bottle. I don't think we'll ever see a cultural figure like Van Cliburn again. Not just a popular performer in classical music but a national hero. And I'm not sure we'll ever see a cultural consensus again like the one that held sway then -- however shakily, however propped up by Cold War competitions and fears.

This history is also relevant because Dr. Smith concludes Money for Art with something like an appeal for a revivified NEA, a call for a back-to-basic-principles endowment, which he sees Dana Gioia as having spearheaded in the last administration. But more than this, Dr. Smith essentially wants to return to that 'unique cultural moment' in the '60s and this time, wiser and older, we'll get the NEA's purpose right.

To earn federal tax money, Dr. Smith says, it's not unreasonable to ask of our renewed endowment, "In what way is art good for a democratic society?" Or more evocatively, he says, "What do the arts provide that America needs?"

And he answers:

Exposure to great art keeps healthy individualism from becoming isolation by reminding people who are exposed to it of their common humanity. Such art provides a touchstone of familiarity -- and therefore collegiality if not community -- in an increasingly displaced society. Great art takes note of those things that are similar, not different, in all people. Lesser forms of art, not to mention popular culture, do not do this. Pop culture, so dominant, is ultimately transient, relentlessly replacing today's art with tomorrow's, watering down the whole concept of art in the process. The critic Mark Steyn has noted that as popular culture crowds out other forms, "eventually you dwindle down to a present-tense culture unable to refer to anything beyond itself. Folk art and controversial art actually work in a similar way, each exulting in its own isolation and reinforcing an identity not of common humanity but only of a compartmentalized block of it. Multiculturalism, so celebrated in contemporary America, is guilty of this on a much larger scale. In seeking to celebrate distinctions it works to calcify those distinctions into divisions. In the face of this, exposure to great art, it would seem, is needed now more than ever.

I would like to see a revivified NEA, and I could see it defining itself, to a degree, against popular culture, against the isolation that modern culture may foster. What, after all, is "non-profit" all about -- if not giving those arts a hearing that don't easily answer to corporate culture's bottom line?

But I wouldn't want to see it happening on Dr. Smith's terms. For starters, the notion that popular culture divides, while "great art" unites will be news to many great artists -- from Goya to the Romantics to JMW Turner to the Impressionists to the Symbolists to the pre-Raphaelites to the pointillists to the Expressionists and so on. Each of these groups, each of these artists, vigorously defined their work against prevailing styles and ways of thought. At first, they didn't unite anything -- except the group of people who appreciated what these controversial artists were doing.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled, ten dollar bill and ink, 2008

At the same time, the idea that popular culture divides and isolates people will be news to, say, the 20 million fans of Celine Dion, who form websites to share information and photos about her, create Facebook identities to communicate their enthusiasm with like-minded people, track her every warble through official calendars and sources. Many artists in any field would love to have that kind of divided, distracted, isolated and alienated audience for their work.

This dismissal of all popular culture is extremely out of

touch with the realities of art and entertainment today -- and not only

for the many ways "high art" and "pop arts" permeate each other. How

shall we consider crossovers? How many CDs or downloads does a serious

classical musician like Yo-Yo Ma have to sell before he ceases to speak

to our "common humanity" and starts "watering down the whole concept of

art" by turning his artistry into another pop culture product (which, apparently, it wasn't beforehand)? It is not possible to be a fine

artist and a tremendously popular one? Then what are we to make of

Charles Dickens or John Singer Sargent? J. D. Salinger and Frank Gehry? I suspect Dr. Smith and Mr. Steyn have very faulty and narrow definitions of what constitutes "popular culture."

Finally, these days, perhaps our

shabbiest, most compromised art form -- television -- has been producing such

programs as The Sopranos, The Wire, Deadwood, Generation Kill and Breaking Bad.

These are masterworks of serialized dramas, some of the most profound

art works we have right now in any genre. I am hardly alone in seeing The Wire as our modern heir to those grand,

grim, urban novels of the 19th century. Creator David Simon marched

through one city institution after another (schools, real estate

development, elections, media) as they all became warped by the forces

of drugs and crime. This is precisely what Tom Wolfe -- oh, back to him --

believed the contemporary American novel must do in his infamous manifesto, "Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast": more reporting, richer, closer, denser examinations of our social institutions. Laura Miller on Salon has even compared The Wire to the Iliad for its "classic," tragic sense of people being trapped by fate. Not what we normally expect from "TV."

In America, the former poet laureate Robert Pinsky has said, we don't have a tradition of "hereditary curators," an aristocratic class imposing its tastes. For better and worse, this has meant we've had to improvise our culture, borrowing bits from Europe, Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America -- then revving them up with new technologies and shady old business practices. As a result, our impurities, Pinsky declared, have been our glory: jazz, blues, Hollywood films, Broadway musicals.

Among other things, I'm a theater critic. I love well-done classic dramas. But ours is the country that invented the tap dance, bluegrass, the banjo, the sitcom and the comic book. It seems un-American that our notion of art that's worthy of funding by the federal government must now be limited to recycled Shakespeare and whatever's safe for children's classrooms.

Categories:

Blogroll

Critical Mass (National Book Critics Circle blog)

Acephalous

Again With the Comics

Bookbitch

Bookdwarf

Bookforum

BookFox

Booklust

Bookninja

Books, Inq.

Bookslut

Booktrade

Book World

Brit Lit Blogs

Buzz, Balls & Hype

Conversational Reading

Critical Compendium

Crooked Timber

The Elegant Variation

Flyover

GalleyCat

Grumpy Old Bookman

Hermenautic Circle

The High Hat

Intellectual Affairs

Jon Swift

Laila Lalami

Lenin's Tomb

Light Reading

The Litblog Co-op

The Literary Saloon

LitMinds

MetaxuCafe

The Millions

Old Hag

The Phil Nugent Experience

Pinakothek

Powell's

Publishing Insider

The Quarterly Conversation

Quick Study (Scott McLemee)

Reading

Experience

Sentences

The Valve

Thrillers:

Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind

Crime Fiction Dossier

Detectives Beyond Borders

Mystery Ink

The Rap Sheet

Print Media:

Boston Globe Books

Chicago Tribune Books

The Chronicle Review

The Dallas Morning News

The Literary Review/UK

London Review of Books

Times Literary Supplement

San Francisco Chronicle Books

Voice Literary Supplement

Washington Post Book World

3 Comments