Money for Art, Pt 1: Arts Funding in America

It's dead certain that our culture wars will rage again.

David A. Smith, a senior lecturer in history at Baylor University, does not actually make that prediction in his book, Money for Art: The Tangled Web of Art and Politics in American Democracy. But it's there. It's there because, according to Dr. Smith, the culture wars have never really ceased fire. Federal support of the arts has been the trigger for an argument, he believes, that has flared on and off practically since the origins of the republic. Dr. Smith's book is the first to study government arts funding in this light.

Of course, the tag "culture wars" was originally coined about the loose but linked political firefights we've had the past two decades. James Davison Hunter's 1991 book, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, popularized the term. Dr. Hunter saw Americans as divided into two polarized moral understandings, the "orthodox" and the "progressive," and he tried to make some historical sense of what has been a tangle of social, political and religious differences, involving creationism, stem-cell research, gay marriage, abortion -- and federal funding of the arts.

Specifically, the confrontation over arts funding was launched in

the late '80s by Republicans in Congress. Senator Alphonse D'Amato,

Senator Jesse Helms, Representatives William Dannemayer and Dick Armey

became incensed over government-funded artworks they deemed offensive.

Or to turn that sequence of events around: The National Endowment for

the Arts provoked a public outcry when it began underwriting artworks

that these members of Congress felt went too far. The works, they

charged, exceeded limits of community taste on matters of sexuality and

faith, they explicitly advocated hostility toward Christianity and a

"homosexual agenda" -- and they did all this with tax money.

But while other people might see the history of arts funding as marked by just these kinds of distinct, historically-bound outcries over decency or budgets, Dr. Smith sees them connected in a long, knotted thread. This thread stretches from 1817 -- when Congress paid to have the first patriotic oil paintings installed in the Capitol Rotunda -- all the way to the just-finished tenure of Dana Gioia as director of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Dr. Smith offers a welcome and clear-headed analysis. He lends coherence to the history of arts support in America -- as a clash of underlying principles about the nature of democracies and government arts funding.

It's just what's lacking from Money for Art that's so dismaying.

For Dr. Smith, our long conflict over federal arts funding has never fully concluded because bankrolling culture in a democracy rests uneasily on two unresolved issues: how the arts are funded and why they are.

First: Who decides which artworks will be backed? The NEA spends our tax money, so we citizens have a say. But if we want to fund greatness in art, greatness is hardly settled by a popular vote. Conveniently for us, American Idol demonstrates this week after week.

On the other hand, letting "experts" decide which are the deserving artworks can lead us back to the culture wars of the '90s when elected officials were outraged by what our experts had chosen. As Dr. Smith puts it, arts funding in a democracy struggles to balance an "elitism of creation" with "an egalitarianism of access." It's a combination that he understandably finds "elusive" -- because both sides, taxpayers and artists, are armed with legitimate arguments.

The fact is that the public already chooses which artworks we want to bankroll -- with our wallets. This system is called popular culture, and whether the entertainment industry's products are good, bad or indifferent, it does create and distribute everything from books to songs to films. So if that's direct support (at the cash register), why do we need indirect support (through federal funding)?

JSG Boggs, Funny money, paper and ink, no date.

Which is the second, more basic conundrum: In a democracy, what's the purpose for government patronage of the arts? Do taxpayers support the arts because we see them as a testament to our values? Do we wish to promote these around the world? Do we pay artists for their work as a kind of economic assistance program? Do we honor and reward our 'masters' of the arts -- because they express, expand and reflect us in ways that commercial culture often doesn't? Do we believe that the arts are beneficial for all?

That doesn't even exhaust the possible goals: Arts funding could simply be aimed at expanding or equalizing our access to those art forms -- live theater, dance, art museums, classical concerts -- that are too local, too small-scale or too costly. For those Americans who don't live near major cultural centers, our federal dollars can help with "distributing" these arts. It can help fund national tours, extend museum hours, encourage community efforts, subsidize arts education.

Faced with such a long shopping list, one may ask,"Why choose? Why can't the NEA try to meet all these needs?" But of course, the NEA has never had the budget to fulfill even half of these goals. As Dr. Smith demonstrates, in trying to meet them, the NEA has found itself yanked by ideological forces and competing constituencies until it has been effectively re-shaped and re-defined.

The

endowment was established in a burst of early '60s idealism and

optimism, driven partly by the desire to create American masterpieces

by underwriting major American artists and institutions. This desire

was whetted by the sense that our culture was finally coming into its

own. Our popular entertainments at the time may have been widely

derided as shallow or crass (formulaic TV westerns, disposable pop

music, campy Broadway musicals). But these were counterweighted by

growing admiration for our new, supposedly more "serious"

accomplishments: jazz, abstract expressionism, modern dance, dramas by

Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, music by such composers as Aaron

Copland and Milton Babbitt as well as the Nobel Prize-winning novels of

Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner.

The

endowment was established in a burst of early '60s idealism and

optimism, driven partly by the desire to create American masterpieces

by underwriting major American artists and institutions. This desire

was whetted by the sense that our culture was finally coming into its

own. Our popular entertainments at the time may have been widely

derided as shallow or crass (formulaic TV westerns, disposable pop

music, campy Broadway musicals). But these were counterweighted by

growing admiration for our new, supposedly more "serious"

accomplishments: jazz, abstract expressionism, modern dance, dramas by

Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, music by such composers as Aaron

Copland and Milton Babbitt as well as the Nobel Prize-winning novels of

Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner.

Indeed, the expressed wish at the time of its establishment was that the endowment might one day find and fund "the American Shakespeare." And to this day, the NEA's slogan remains "A great nation deserves great art."

Ron English, Money is the Root of All Art, 1994

But in the Reagan-Bush '80s, when the NEA came under fire from fiscal conservatives, and in the Bush and Clinton '90s, when it faced the wrath of social conservatives, the agency barely survived. It did so chiefly by emphasizing the goals of education and expanded access. The NEA shifted its purpose to bringing art (more traditional, more widely acceptable art) to Americans, especially schoolchildren. It had been doing this all along, but it redoubled those efforts, and it reformed its indirect grant procedures. These were too hot, too risky in the new political climate because of the uproars over Robert Mapplethorpe's homoerotic photography and Andres Serrano's urine-soaked crucifix. These artists had not actually received direct NEA grants, but that hardly mattered in the fracas that was ignited over their works.

In those uproars in the '90s, Dr. Smith argues -- convincingly, I believe -- that artists and arts advocates made a serious mistake in logic, law and public relations by repeatedly proclaiming that their First Amendment rights against censorship had been violated. An artist has the right to express himself as he pleases; he hardly has the right to have that expression automatically funded by the government.

On this point, the NEA Four -- the performance artists whose projects were vetoed by NEA head John Frohnmayer in 1990 -- were a different matter precisely because they had a free speech claim. Their projects had won approval before being vetoed; they won their court case. But they lost the war. It was the NEA Four's court case that led an infuriated Congress to kill all individual grants. And although the case was resolved in the NEA Four's favor, the Supreme Court also said that the NEA could, in fact, insist on 'decency standards.'

So this is what the NEA does today: With its very modest budget, it increases public access to the arts, it researches and documents our declining literacy rate and in its "Shakespeare in American Communities" program, it promotes tours of the original (not the American) Shakespeare. It also insists on decency standards. The goal of finding and developing new, "great art" by individuals is not really on the agenda anymore, despite the slogan. As Roger Kimball put it in the National Review, hailing the changes brought about by NEA head Dana Gioia: "Farewell Mapplethorpe, Hello Shakespeare." To Kimball, this has represented a victory of hallowed tradition over trendy, "Pomo" transgressions. For Kimball, it seems, those were the only choices to fund.

Dr. Smith puts this development in a different context, asking, is the NEA an "I" (created to serve the artist and her art) or is it a "We" (created to serve the taxpayers and the wider community)? In the '90s, Dr. Smith notes approvingly, that question was finally settled. The NEA is a "We."

On the face of it, this is simple common sense. The National Highway

Traffic Safety Administration does not exist for the benefit of guard

rail manufacturers. It exists to improve our chances of surviving a

road trip. But Dr. Smith's polarization of the interests of "I" and

"We" is too easy. The Environmental Protection Agency exists to protect and preserve the environment for the benefit of all Americans.

Ergo, one can make the case that in many instances, helping the "I"

(the artist and her art) can actually serve the greater good of the

"We" (the rest of us).

Critics and pundits have made a number of these same points before. But Money for Art is the first book-length study that examines the long course of federal cultural programs through the lens of these tensions, tensions inherent in all democratic arts funding: Taxpayers pay, therefore taxpayers should control. Yet taxpayers are not necessarily in a position to judge great art. So the NEA is -- and has always been -- in the awkward position of advocating "elitist" art for "democratic" purposes.

Along with this analysis, Money for Art offers a revisionist

history of the endowment. Dr. Smith clearly seeks to debunk popular

conceptions about presidential administrations and the arts. (Test your

knowledge with the Arts Funding Quiz on the Art&Seek blog.)

Briefly put: Ever since John Kennedy publicly feted renowned artists at the White House, Democratic presidents have been greeted with the expectation that they will usher in a new era of cultural achievement -- despite evidence to the contrary. Jimmy Carter, for example, had actually cut the arts budget in Georgia when he was governor. He was still (ultimately) the candidate of the arts establishment.

So it's ironic that Richard Nixon proved to be the endowment's best friend in the White House. According to Dr. Smith, Nixon hoped the NEA might counter prevailing cultural currents, which he saw as divisive and anarchic. In this way, Nixon apparently saw the arts as a vital cultural force and arts funding as a worthwhile government endeavor, attitudes Dr. Smith would wish to foster.

In much of this, Money for Art is admirably sensible, trying to wend its way between conservative and liberal, public and artist, untangling the claims and counter-claims of each. What is maddening about the book -- even startling -- are its huge oversights and its blinkered views about the highly politicized nature of the arts funding debate in America over the past 70 years.

Chief among the oversights is Dr. Smith's strangely cursory treatment of the arts programs of the Works Progress Administration under Franklin Roosevelt. The Federal Theatre Project, the Music Project, the Art Project and the Writers' Project were essentially the NEA's predecessors, yet the primary reason Dr. Smith discusses the WPA at all is to uncover the source of what he sees as a common misconception -- the idea that, even today, federal arts funding is a jobs program. The WPA, he argues convincingly enough, was designed as a temporary, Depression-era, emergency measure and not a new alignment of the government with the artist.

What the author fails to recognize is that the fierce partisan conflicts in the late '30s over the WPA sketched out the battle lines for the full-bore culture wars of the '80s and '90s.

First, Republicans -- and a sizable number of conservative Southern Democrats -- vehemently opposed the WPA not simply because it was part of Roosevelt's economic recovery program. They feared that with the WPA, Roosevelt was underwriting a new liberal political machine. He was buying votes with jobs. They also feared that the WPA's arts programs were little more than a propaganda arm for FDR.

But in opposing the WPA and what it represented, Republicans and conservative Democrats faced major difficulties -- ones that may sound rather familiar today. They were tied to what had turned out to be catastrophic economic policies. They'd been swept out of their long-held control of Washington and they faced a president who was personally very popular, who had a sizable mandate for change.

So

they picked up the only charges they had that gained public attention

and undercut the authority of the Roosevelt administration: government

waste and Communist subversion. And to varying degrees, the WPA was

vulnerable on both charges. I won't go over the protracted in-fighting,

but two histories worth reading, two books with very different

perspectives on this period, are Ted Morgan's Reds: McCarthyism in 20th-Century America, a survey of our government's pursuit of Communist infiltration, and Nick Taylor's American Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA -- When FDR Put the Nation to Work.

Two points need to be made about the WPA battle, however. One, the attack on federal arts programs had little to do with the arts or with arts funding. The WPA could have been producing Art Deco-style widgets. The arts -- provided they could be portrayed as wasteful or dangerously Communist-controlled -- were mostly just a club to use against the New Deal.

And two, the club was more or less successful. The WPA wasn't completely disbanded until 1943 when wartime employment rendered it unnecessary. But before then, Republicans and their Democratic allies did manage to stall, even derail, the federal arts programs and they damaged the WPA's effectiveness, blunting some of the administration's power and authority.

It's certainly true that many people opposed the WPA and its arts programs out of honest economic and political disagreement. Amity Shales, author of The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, argues that the arts are not really the province of government and that what the New Deal accomplished through the WPA could have been done through private sources.

Still, regardless of the economic principles at stake, opposition to the New Deal at the time devolved into an ugly Congressional investigation led by Texas Representative Martin Dies' House Un-American Activities Committee. The committee turned most of its attention on the WPA, calling witnesses to testify against the agency, especially its arts programs. These charged the Federal Theater Project with, among other things, whites and blacks fraternizing under its auspices "like Communists" (certain to rile Southern segregationists). Then there was the committee's grilling of FTP leader Hallie Flanagan about a playwright she'd cited in an article. "Is he a Communist?" a committee member demanded.

"Put it in the record," Flanagan replied patiently, "that Christopher Marlowe was the greatest dramatist in the period ... immediately preceding Shakespeare."

Eventually, the HUAC report to Congress denounced "a rather large

number of the employees of the Federal Theatre Project" as either

outright Communist party members or CP sympathizers, although it had

never actually established this. (See Taylor, pp. 409-426.) Congress

was furious at the FTP. It was tired, as well, of finding that on the

Federal Arts Project's many frescoes, artists had painted images of

factory hands holding copies of The Masses. For the 1940

appropriations bill, Congress pointedly "zeroed out" the Federal

Theatre Project. It gave the other arts programs directly over to the

states for sponsorship (where they often languished) and among other

changes, enacted a "loyalty oath" that all WPA employees had to sign. Shades of the "decency" standards NEA grant recipients must agree to now.

In other words, using the WPA's cultural programs against the New

Deal was effective. It inflamed opposition to Roosevelt, created a

counterweight to the administration's promotional efforts at job

creation, sullied New Deal programs as both wasteful and

Communist-influenced. In the end, these efforts inflicted budget cuts

and political losses on the administration. Harry Hopkins, FDR's most powerful and polarizing aide, resigned from running the WPA to become Secretary of Commerce -- a post he also resigned. He'd once been considered FDR's handpicked successor.

These weapons proved effective enough to be picked up and used again -- a decade later. In the '50s, President Dwight Eisenhower was often portrayed as culturally clueless in a culturally vapid time. Dr. Smith devotes much of an engaging and persuasive chapter ("Paint by Numbers") to rehabilitating Eisenhower's reputation on such matters. Eisenhower, for instance, was the first president to see the efficacy of "culture as a weapon" in the Cold War, making the United States appear as a country worth respecting, even emulating, for something more than our materialism or military might.

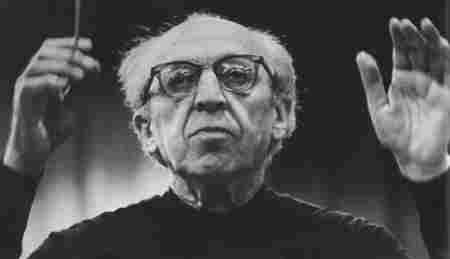

Yet Dr. Smith never mentions that for Eisenhower's inauguration, Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait

was originally scheduled for a concert. A single, Republican

congressman, Fred Busbey of Illinois, complained that Copland was a

contributor to left-wing (i.e., Communist front) causes. Not wishing to

alienate the conservative bloc that already was deeply suspicious of

him, Eisenhower immediately dropped Copland's music from the program.

Yet Dr. Smith never mentions that for Eisenhower's inauguration, Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait

was originally scheduled for a concert. A single, Republican

congressman, Fred Busbey of Illinois, complained that Copland was a

contributor to left-wing (i.e., Communist front) causes. Not wishing to

alienate the conservative bloc that already was deeply suspicious of

him, Eisenhower immediately dropped Copland's music from the program.This public embarrassment became a public nightmare when Senator

Joseph McCarthy picked up the scent of media attention and subpoenaed

Copland to appear before his investigatory subcommittee. Because some

of McCarthy's Red-bashing was tied to the FBI's "queer-hunting,"

Copland had several reasons to be terrified that his career as one of

America's rare, beloved classical composers was over.

The results were more pointless than usual for the subcommittee: Copland later wrote that he believed McCarthy wasn't even certain who he was or why he was being questioned. In the end, the composer managed to appear politically naive before the senators, who saw no threat in him. Yet Copland still lost paying gigs on political grounds and was apparently deemed a "security suspect." (See Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise, pp. 412-414).

More tellingly, around the same time that Copland faced the Senate subcommittee, McCarthy called for dismantling the overseas libraries that the Voice of America ran in Europe. The libraries were an example of Cold War federal arts patronage: They spread American ideas and literature abroad. But McCarthy objected to their stocking such "anti-American" authors as Langston Hughes. During the course of deliberations with the Eisenhower administration on the issue, McCarthy aide Roy Cohn suggested that the government shouldn't stop with banning books. The libraries should ban music as well.

And why not start with Aaron Copland's? (See Reds, pp. 446-447).

Just how instrumental Copland's "Appalachian Spring" might be in recruiting listeners to Marxist economic theory is difficult to imagine. But then, that wasn't the concern of the investigations. The point was to use government powers and public hysteria to punish, tarnish or intimidate political enemies, including prominent artists.

Robert Dowd, Van Gogh Dollar, acrylic on canvas, 1965

It could be argued that much of this -- especially the Communist-hunting -- isn't really part of Dr. Smith's purview in Money for Art. But insofar as the book concerns the relationship between our government and the artists it funds -- as well as taxpayers' attitudes towards the arts -- this history is obviously pertinent. The attacks on the WPA via its arts programs and the McCarthy investigations into individual artists were deeply anti-intellectual and fearful of the arts as somehow subversive, elitist, fraudulent (not "real" art), "provocative" (politically, racially and sexually), dangerously anti-American and a waste of public money. These suspicions remain motivating impulses in the arts funding debates today -- even more evidence, it would seem, for Dr. Smith's contention that the culture wars existed well before the '90s.

In 1960, it was in light of all this political demonizing -- and in light of the more infamous case of the Hollywood Ten -- that we can understand what it meant to artists and the arts establishment when John Kennedy invited Leonard Bernstein to participate in his presidential inauguration. Bernstein was an even more publicly left-wing figure than Copland. He'd been blacklisted by CBS and the State Department from 1950-'54. It was a sign that McCarthy-ite attacks on the arts were over -- at least for now.

And then, when Pablo Casals was hosted at the White House, the Kennedys invited Copland, too.

I've lingered over all this political history from the '30s to the '60s because Dr. Smith devotes entire chapters to the arts policies of Eisenhower and Kennedy. And he does touch upon the Casals-Copland-Bernstein visits to the Kennedy White House.

Other than that, virtually nothing else I've included here is discussed in Money for Art.

The important conclusion to draw from this history is this: Being used as a weapon or a whipping boy has been a political function that the arts have repeatedly been dragged into well before the '90s. Of course, sometimes artists weren't dragged at all; they joined the fray willingly, eager to stick a thumb in the eye of the bourgeoisie, and then demand federal payment for the service. Dr. Smith quotes any number of artists over the years making inflammatory or confrontational tirades -- often being their own worst enemies when it came to courting Congressional or public approval.

Yet such statements only made it easier for politicians to pick up the weapon that was already there and had been proven effective -- using the arts as a flash point to inflame anger and suspicion against their political opposition, to punish that opposition. The fact is that tarring the arts (and arts supporters) has repeatedly worked as a political attack strategy, especially when artists, arts organizations and the NEA are used as stand-ins for a supposedly decadent, educated, effete establishment, whether that's in Hollywood, New York or Washington, D.C.

So alongside Dr. Smith's contesting democratic principles, I would place partisan warfare as an explanation for why the arts have been a persistent but intermittent casus belli since the New Deal. When it comes to arts funding, the culture wars have been a war by proxy, a war fought by liberals and conservatives for public approval, moral standing, government power and money, a war fought through the arts and not necessarily because of the arts.

(originally published at Artandseek.org.)

The conclusion in Money for Art, Pt. 2: Re-Playing the '50s and the '90s

Categories:

Blogroll

Critical Mass (National Book Critics Circle blog)

Acephalous

Again With the Comics

Bookbitch

Bookdwarf

Bookforum

BookFox

Booklust

Bookninja

Books, Inq.

Bookslut

Booktrade

Book World

Brit Lit Blogs

Buzz, Balls & Hype

Conversational Reading

Critical Compendium

Crooked Timber

The Elegant Variation

Flyover

GalleyCat

Grumpy Old Bookman

Hermenautic Circle

The High Hat

Intellectual Affairs

Jon Swift

Laila Lalami

Lenin's Tomb

Light Reading

The Litblog Co-op

The Literary Saloon

LitMinds

MetaxuCafe

The Millions

Old Hag

The Phil Nugent Experience

Pinakothek

Powell's

Publishing Insider

The Quarterly Conversation

Quick Study (Scott McLemee)

Reading

Experience

Sentences

The Valve

Thrillers:

Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind

Crime Fiction Dossier

Detectives Beyond Borders

Mystery Ink

The Rap Sheet

Print Media:

Boston Globe Books

Chicago Tribune Books

The Chronicle Review

The Dallas Morning News

The Literary Review/UK

London Review of Books

Times Literary Supplement

San Francisco Chronicle Books

Voice Literary Supplement

Washington Post Book World

5 Comments