It's taken me awhile to get around to this -- busy, busy, busy -- but Katie Roiphe wrote an essay, "The Naked and Conflicted," for the cover of last Sunday's New York Times Book Review. It's an essay that's generated a great deal of online talk because in it, Roiphe looks back with a certain wistful fondness for the old

caveman sexuality of the earlier generation of leading American white male

novelists (Roth, Mailer, Updike).

It's taken me awhile to get around to this -- busy, busy, busy -- but Katie Roiphe wrote an essay, "The Naked and Conflicted," for the cover of last Sunday's New York Times Book Review. It's an essay that's generated a great deal of online talk because in it, Roiphe looks back with a certain wistful fondness for the old

caveman sexuality of the earlier generation of leading American white male

novelists (Roth, Mailer, Updike).

They were the boundary-breaking 'bad boys' who -- however negligible it is as an ontological proposition -- exalted sexual conquest as a defining activity. Let's imagine them all as a kind of writerly version of Jack Nicholson. In contrast, the newer batch (David Foster Wallace, Michael Chabon, et al) are the insecure nice guys who doubt that chest-thumping and skirt-chasing should define their existence as men. They're the self-conscious nice guys whom feminists like Roiphe now seem a little fed up with. No grand flights of lust-filled poetic fancy from them. So let's imagine them as John Cusack.

Actually, I would posit a different way of distinguishing Ms. Roiphe's two

groups. The new guys -- at least in their fictional male protagonists --

seem to care about what their female bed-mates think, desire,

hope for, derive pleasure from. The older ones seem far more selfish. In this, Roiphe has missed the crux of David Foster Wallace's attack on John Updike's approach to sex in his male characters. Simply put, the Updike character's crude-ish thinking on sex in no way matches Updike's own super-subtle thinking about other areas. Consequently, Updike's fiction repeatedly conveys the attitude that sex is something a man takes or cheats out of a woman -- for him, sex is barely worth considering in depth outside of his own obsession. Hence, Foster Wallace's conclusion that Updike's (repeated) attitudes toward sex suggest something deeply unpleasant about him.

Yet Ms. Roiphe

longs for some of that old, lust-filled transcendence,

both emotional and literary, and seems to think this is the only way it arrives. One wonders how such transcendence (literary and sexual) is achieved when it comes with a lack of respect, but then, that's how some people like it. Apparently, though, Ms. Roiphe still wants to be

desired and fought for but not denigrated or dismissed.

So we're back with what do women want? And for Ms. Roiphe, it

would seem they want that traditional, bifurcated being: a gentleman at the dinner

table, a Visigoth in the bedroom. She wants Nicholson and Cusack.

Good luck finding and keeping such a creature -- because he's more or less a fantasy, much like the male fantasy of the happy, lust-filled bimbo who will deliver a beer and then disappear. There's no problem with fantasy figures provided they're recognized as such and we understand what this fantasy says about us. But Roiphe never recognizes the fantasy element in her argument at all. To put it in a more literary, less Hollywood way, she wants a feminist Philip Roth. As I said, good luck with that.

A version of this was sent to the NYTimes Paper Cuts blog.

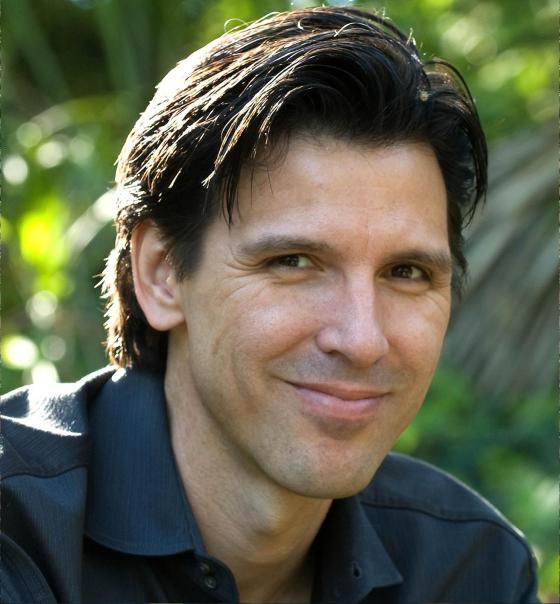

Over at Art&Seek, you can watch my Think TV video interview with Texas author Oscar Casares. We talk about family legends, storytelling, his new novel, Amigoland, and how un-exotic and everyday the border is in his fiction -- in contrast to, say, Cormac McCarthy's novels, where it's this life-changing moment when a young Anglo crosses it to learn about Love and Death. In Amigoland, two aging, quarreling Mexican-American brothers head south to determine whether if a story their grandfather told is true.

Over at Art&Seek, you can watch my Think TV video interview with Texas author Oscar Casares. We talk about family legends, storytelling, his new novel, Amigoland, and how un-exotic and everyday the border is in his fiction -- in contrast to, say, Cormac McCarthy's novels, where it's this life-changing moment when a young Anglo crosses it to learn about Love and Death. In Amigoland, two aging, quarreling Mexican-American brothers head south to determine whether if a story their grandfather told is true.

Attica Locke is a bit of a rarity. She's an African-American, female novelist from Texas who's made her debut with a big-city crime novel. It's called Black Water Rising, and rarer still, Locke is getting compared to such master thriller writers as Dennis Lehane, the author of Mystic River, and George Pelecanos, who wrote for the HBO series, The Wire.

Locke has already been a successful screenwriter in Los Angeles for more than a decade. But while her scripts got sold they never got made. Partly, this was just because of the cumbersome economics of filmmaking. Partly, it's Hollywood's very limited openness to serious movies about African-Americans.

So Locke decided that this time, she'd write a novel. And she'd set it in Houston in 1981. She was inspired by an incident that happened when she grew up there.

ATTICA LOCKE: "My dad, who did not have a lot of money, wanted to do something for my step-mother, for her birthday. And he knew somebody who knew somebody who ran boat tours on Buffalo Bayou. And you dock in downtown Houston which is kind of, you know, city lights and somewhat picturesque, but the ride takes you into parts of the city that are not so nice."

Somewhere in the darkness, a woman screamed. Then, gunshots. Locke's father did not play hero. He wasn't going to endanger his wife and children by abandoning them to leap unarmed into a swamp at night.

In contrast, in the opening of Black Water Rising, Attica's main character, Jay Porter is in the same situation. But he jumps.Allison McElroy, 411 #2, rolled-up phonebook pages, wire, black frame, 2009

Anarchic and whimsical, Fluxus was a little-known art movement in the '60s -- little-known, even though Yoko Ono was an occasional and influential Fluxite. (John Lennon once quipped that everyone knew who Yoko was yet no one knew what she did.) But the movement arguably died out in the '70s -- although a Fort Worth artist, author and home-grown museum curator disagrees. As proof, he has assembled the current show, Fluxhibition #3, in the student gallery at the University of Texas at Arlington.

And then there's his living room.

Most art museum directors would have us believe that running an art museum is an all-consuming job. Yet Cecil Touchon runs two, three, maybe four -- out of his own living room.

TOUCHON: "We're standing in the living room of a three-bedroom, ranch-style house in Fort Worth, and the entire living room is wall-to-wall metal shelving housing boxes, plastic containers full of collages and arts supplies."

These are not just any overflowing shelves. Touchon is a successful artist with his boldly-colored collage works selling in New York and Santa Fe galleries. They've been featured in Interior Design magazine.

Official Fluxmuseum interior

But what's taking over his house are other people's artworks. For a decade, Touchon has been exchanging pieces through the mail with fellow artists. The resulting collections he's boxed up and crowded into his living room.

TOUCHON: "It's all part of the Ontological Museum of the International Post-Dogmatist Group. There's the FluxMuseum, the International Museum of Collage, Assemblage and Construction, and then Fluxus Laboratories is here. Oh, and FluxShop. Yeah - you know you've got a real Fluxus product when you have a FluxShop gold stamp on it like these. [laughs]"

If you want to read a book on Fluxus, I'd recommend Fluxus Codex, and there's even an irreverent cartoon history of the movement (A Flexible History of Fluxus Facts & Fictions) by a longtime Fluxite, Emmett Williams

How to Sell: I love the title with its echoes of business advice books. It's easy to imagine someone picking up Clancy Martin's novel to get tips on closing a sale - only to get a shock.

But I hope the book buyer will keep reading. How to Sell is told by a 16-year-old named Bobby Clark. Bobby is expelled from his Toronto high school and heads for Fort Worth. His brother Jim offered him a job there in a jewelry emporium. Bobby is naïve but he's also amoral. He steals his own mother's wedding ring to pawn for cash. But he does it all for a girl he loves -- who doesn't even care about him.

People mistake Bobby's bewilderment and eagerness for innocence. But he also has this talent. Working in the Fort Worth jewelry store may teach Bobby how to fake white gold as platinum, how to pass off a cheap, used Rolex as a brand new expensive model. And he certainly learns a lot about using booze, cocaine and crystal meth to get through the frantic days on the selling floor.

But when it comes to selling, that's an art young Bobby Clark has in his family DNA. Bobby and Jim's father is an ailing New Age minister, part guru, part con-man. He keeps popping up whenever his latest church has failed or whenever he needs serious medical help. Bobby says that his father had lied to him thousands of times. And if you told him he'd lied he would deny it with a sincere heart.

Justine Smith, Absolute Power, dollar bills, 2005

Money for Art, Pt 1: Arts Funding in America

David A. Smith's Money for Art: The Tangled Web of Art and Politics in American Democracy recounts the history of federal funding of the arts since 1817 when Congress bought its first set of oil paintings. But Dr. Smith -- a senior lecturer in history at Baylor University -- mostly gets through the decades up to the 1960s to set up his account of the National Endowment for the Arts, which is more or less the heart of the book. Indeed, it's possible to read Money for Art as an extended preamble to the NEA's culture wars in the '80s and '90s. The book is an attempt to explain that outbreak by putting it in a historical context -- to explain it, learn from it and perhaps even get past it.

Dr. Smith believes that since the '60s, the NEA -- and American culture in general -- has gone too far in valuing (even celebrating) the needs and impulses of the individual artist. Built up over the course of several chapters, Dr. Smith's argument is that by the '80s, the arts and the NEA had become estranged from much of the American public (and its political leaders). They had discredited themselves in the eyes of many by becoming over-intellectualized, over-concerned with 'transgression' and 'revolution' for transgression and revolution's sake. The NEA was increasingly beholden to a small, insular set of art-world postures and lefty academic opinions. It had embraced a multi-cultural pluralism, thereby surrendering whatever authoritative judgments the endowment made on the artworks it chose to fund.

A backlash from taxpayers and political leaders was bound to happen.

A good case can be made for some of this. Some of it -- no. To take one example: Citing Tom Wolfe's The Painted Word, Dr. Smith presents the idea that the arts have become increasingly esoteric, obsessed with critical theory and have deliberately dismissed a middle-class audience's understanding.

Undoubtedly, some have. But there are two chief weaknesses with this

view. First, as Dr. Smith more or less recognizes, it applies a

situation in the visual arts to all the others. In fact, Money for Art

is often limited by Dr. Smith's reliance on building his case through

the visual arts. Although he makes reference to the other arts, the

great majority of his evidence, his thinking, his history, is derived

from painting and photography.

It's dead certain that our culture wars will rage again.

David A. Smith, a senior lecturer in history at Baylor University, does not actually make that prediction in his book, Money for Art: The Tangled Web of Art and Politics in American Democracy. But it's there. It's there because, according to Dr. Smith, the culture wars have never really ceased fire. Federal support of the arts has been the trigger for an argument, he believes, that has flared on and off practically since the origins of the republic. Dr. Smith's book is the first to study government arts funding in this light.

Of course, the tag "culture wars" was originally coined about the loose but linked political firefights we've had the past two decades. James Davison Hunter's 1991 book, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, popularized the term. Dr. Hunter saw Americans as divided into two polarized moral understandings, the "orthodox" and the "progressive," and he tried to make some historical sense of what has been a tangle of social, political and religious differences, involving creationism, stem-cell research, gay marriage, abortion -- and federal funding of the arts.

Specifically, the confrontation over arts funding was launched in

the late '80s by Republicans in Congress. Senator Alphonse D'Amato,

Senator Jesse Helms, Representatives William Dannemayer and Dick Armey

became incensed over government-funded artworks they deemed offensive.

Or to turn that sequence of events around: The National Endowment for

the Arts provoked a public outcry when it began underwriting artworks

that these members of Congress felt went too far. The works, they

charged, exceeded limits of community taste on matters of sexuality and

faith, they explicitly advocated hostility toward Christianity and a

"homosexual agenda" -- and they did all this with tax money.

But while other people might see the history of arts funding as marked by just these kinds of distinct, historically-bound outcries over decency or budgets, Dr. Smith sees them connected in a long, knotted thread. This thread stretches from 1817 -- when Congress paid to have the first patriotic oil paintings installed in the Capitol Rotunda -- all the way to the just-finished tenure of Dana Gioia as director of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Dr. Smith offers a welcome and clear-headed analysis. He lends coherence to the history of arts support in America -- as a clash of underlying principles about the nature of democracies and government arts funding.

It's just what's lacking from Money for Art that's so dismaying.

Although Seven Pleasures: Essays on Ordinary Happiness is getting shelved in the "self-help" sections -- and more power to that label if it means the book will sell better than the usual essay collection -- Willard Spiegelman's new volume is actually a set of reflections on a set of quotidian activities: reading, walking, looking, dancing, listening, swimming and writing. His pieces are classic essays in the humanist tradition that goes back to Montaigne. They're part personal memoir, part guide, part explanation, part appreciation, part conveyor of insight, whether it be practical, moral, political or philosophical. The essays are all very much in the voice of this Southern Methodist University literature professor and longtime editor of Southwest Review: elegantly phrased yet seemingly casual, bemused yet thoughtful. And, of course, literate and learned but not in an off-putting manner. Think of it as a likable donnishness. It's that voice, that ruminative process of thinking that is one of the book's enjoyments. It succeeds so well in leading a reader along.

In his introduction, Spiegelman explains that he comes from cheerful stock. His outlook on life, as most of ours have, has been shaped by his genes. As he says in our televised conversation (which you can see at Art&Seek), he could do without these activities, these pleasures, and still be cheerful. This is one of the rare places in Seven Pleasures that I parted company with the likable don.

Obituaries described Horton Foote, who died Wednesday, as a great storyteller, a writer of ordinary Americans. To me, these sound just a little condescending. For them, Foote is not a great dramatist on par with an Albee or Mamet. He's a great storyteller - as if he were some folksy character on a front porch just spinning yarns about his kin.

It's easy to get this impression. I confess I held it at first. Foote never went to college (although he and his wife did end up running a school in Washington, D.C.) Some of Foote's earliest works - like The Trip to Bountiful - were written for television, and they remain some of his most popular. They're also his most sentimental. The characters here express what they feel and act on those feelings. End of story. The small town settings, the countryfied language, the homey qualities: Nothing much will surprise you.

The New York Times obituary claimed, unsurprisingly, that the Times' theater critic Frank Rich was partly responsible for rediscovering and reviving Foote's career. Actually, for anyone who was paying attention, the change was apparent with the 1983 film, Tender Mercies, in which Robert Duvall plays a washed-up, drunken country singer. And won an Oscar.

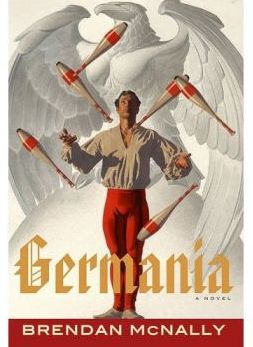

What is it with North Texas novelists making their debuts with really oddball thrillers?

What is it with North Texas novelists making their debuts with really oddball thrillers?

Four years ago, Will Clarke appeared with Lord Vishnu's Love Handles. The novel combines terrorism, Dallas social satire and a Hindu apocalypse. It doesn't always work, but Lord Vishnu surely ranks as one of the stranger, more amusing entertainments by a local writer.

Now comes Brendan McNally (below) with his first novel, Germania. Germania was Adolf Hitler's name for his future world capital in Berlin. It's a terrifically ironic title because McNally's novel is about a German reich very few have ever heard of. Most histories of Nazi Germany end with the complete flameout of the final days in Berlin. They rarely handle what happened next.

A caretaker government was formed in a town called Flensburg. Its basic purpose was to hold on long enough to surrender to somebody. Instead of Hitler's Thousand-Year Reich, Flensburg was the three-week Reich.

So far, so fascinating.

Writers such as Alan Furst and Philip Kerr have uncovered these kinds of nuggets to craft superb thrillers about World War II. McNally is a former defense journalist, so the military history is a natural for him.

About

A professional critic for more than two decades, Jerome Weeks is the arts producer- reporter for KERA, the NPR/PBS station for Dallas-Fort Worth. Before that, he was the book columnist for The Dallas Morning News for ten years ...

more

A professional critic for more than two decades, Jerome Weeks is the arts producer- reporter for KERA, the NPR/PBS station for Dallas-Fort Worth. Before that, he was the book columnist for The Dallas Morning News for ten years ...

moreBook/daddy's motto: Pereant qui ante nos nostra dixerunt! (Roughly: All those who published before us can go to hell.) --- Saint Jerome, quoting his old teacher, Aelius Donatus. Jerome is the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists. Not surprisingly, given the above sentiment, he has also been proposed as the patron saint of bloggers.

Book/daddy's logo: Only real book/daddies have it.

Book/daddy's name puns on bone daddy and mack daddy. Think of it as Pimp My Read....

more

Contact me Click here to send me an email... more

Blogroll

Critical Mass (National Book Critics Circle blog)

Acephalous

Again With the Comics

Bookbitch

Bookdwarf

Bookforum

BookFox

Booklust

Bookninja

Books, Inq.

Bookslut

Booktrade

Book World

Brit Lit Blogs

Buzz, Balls & Hype

Conversational Reading

Critical Compendium

Crooked Timber

The Elegant Variation

Flyover

GalleyCat

Grumpy Old Bookman

Hermenautic Circle

The High Hat

Intellectual Affairs

Jon Swift

Laila Lalami

Lenin's Tomb

Light Reading

The Litblog Co-op

The Literary Saloon

LitMinds

MetaxuCafe

The Millions

Old Hag

The Phil Nugent Experience

Pinakothek

Powell's

Publishing Insider

The Quarterly Conversation

Quick Study (Scott McLemee)

Reading

Experience

Sentences

The Valve

Thrillers:

Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind

Crime Fiction Dossier

Detectives Beyond Borders

Mystery Ink

The Rap Sheet

Print Media:

Boston Globe Books

Chicago Tribune Books

The Chronicle Review

The Dallas Morning News

The Literary Review/UK

London Review of Books

Times Literary Supplement

San Francisco Chronicle Books

Voice Literary Supplement

Washington Post Book World