main: February 2010 Archives

A Whole Lot of Nothing

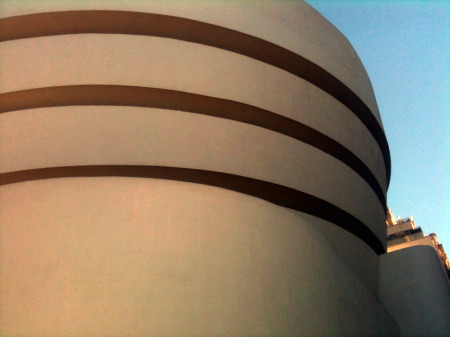

Tino Sehgal has managed to fill the Guggenheim without giving us much to see. But there is plenty to like, not the least of which is the interior of the Frank Lloyd Wright monument to Frank Lloyd Wright. The Guggenheim, all spiffed up at last, has never looked better. It's the 50th anniversary. My, how time flies...or doesn't.

The mother of all museums-as-icons (which is a lot to answer for), the kooky Guggie presently looks particularly good because there are none of those annoying paintings by Kandinsky getting in the way of the architecture. Also, the architecture in the 1936 film Things to Come has long been forgotten, as has the 1939 New York World's Fair and numerous washing machines that predated the look of Wright's pregnant building -- the inside of which is now all lobby, definitely a first.

I have already written an essay about the empty gallery as an artwork upon the occasion of the "Voids: A Retrospective" at the Pompidou last year. But there is so much more to say.

I have nothing but praise for the Guggenheim's daring move. Two works by Sehgal (to March 10) allows the museum to have it both ways: celebrating the restoration of a masterpiece building and climbing on the performance-art bandwagon, now that the painting and sculpture revival that supposedly wiped out Conceptual-type art has come up empty. Retrospectives for David Salle, Julian Schnabel, or even Jean-Michel Basquiat? Well, not yet, or possibly ever. On the other hand, MoMA is presenting a full retrospective of the performances of Marina Abramović (opens March 14), which will include photos and other documents, videos, "re-performances" and a new work.

Also, an empty museum is very cost-effective, as is performance art. No shipping, packing, framing. The anti-materialist performance strand has reappeared, snaking over and under whatever strands were hiding it in our newly formulated art-history braid. Minimalism is beginning to look luxurious and transcendent.

Nevertheless, in the case of Sehgal even less would have been more. His Kiss (2002) is unnecessary ballast, ruining the metaphor of empty museum = empty art = empty world.

The most important thing about the exhibition is the serenity of a nearly empty museum. Therefore, Sehgal's exhibition would also be better without Anish Kapoor's Memory, a welded Cor-Ten steel Easter egg off to the side. And certainly would be better too without the dreary sideshow of modernist masterpieces offered as a sop to tourists. Visitors should be dutifully looking instead for the wall that sports a void that allows you to look inside Memory.

En Garde: Off-Ramp Rants

Of course, you will be yelled at by a nearby guard if you actually come close enough to look inside of Memory -- at a whole lot of nothing. Stay behind the line! Stay behind the line! The line is a small strip of tape on the floor in front of the velvety rectangular hole in the wall.

The guard that roared, by the way, was not a guard I would want to see performing Sehgal's recent Lyon Biennial piece called Selling Out (as reported in the New York Times magazine section a while back). A guard or someone dressed as a guard was paid to slowly strip naked.

Sorry, I know I am being politically incorrect. You probably know that Sol LeWitt once worked as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, as did the painter Robert Ryman. Just remember this: the guard that yells at you may be next in line for a midcareer survey. Just not the ones at the Guggenheim, if I have anything to say about it.

Then we almost had our iPhone confiscated by another improperly trained, super-aggressive Guggenheim guard. So, unlike the Times, which used an iPhone pic of Kiss (2002) to illustrates its review of the show, Artopia will honor Sehgal's stricture against photography of his work -- throughout all eternity. Let's see where that gets him. Opening receptions and catalogues are not allowed either.

Kiss, borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art, was purchased by that institution for $70,000. This is one work from an edition of six and was sold solely by verbal agreement. Sehgal can purge art of materiality and paperwork, but not of cold, hard cash. Thus, it is all too obvious that Sehgal (33, born of a Pakistani father and German mother in Great Britain but now residing in Berlin) once studied economics -- often referred to as the dismal science, but now enjoyed as the satirical path.

It is obvious that he does not bear truck with the "Scholar Artist" ideal initiated in 16th-century China, according to which it is too vulgar to sell your work or accept commissions -- only artisans do that.

It is also obvious that he studied dance. Kiss could be a choreographer's bow to Rodin. On the empty floor of the Guggenheim rotunda, a succession of prone performers goes through the motions of imitating statues of couples in various erotic poses. Too bad I loathe Rodin. Too bad I would rather have seen all the couples naked.

The couples throughout the day consist of various combinations of gender and skin color; but are age-matched, so there is not a hint of the ever-threatening gerontophilia.

What could I or anyone else do with a digital photo of these sentimental moves? Sell it and make money? Plagiarize dance-that-is-not-quite-dance, make replicas of art-that-is-not-quite-art? Hell hath no fury like a photographer scorned.

I sealed my revenge by writing in my tiny, unobtrusive notebook: If you can steal an artwork by taking a picture of it, then it isn't much of an artwork.

Another Day, Another Rant

Speaking of notebooks, way downtown at a certain non-museum that calls itself a museum although it has no permanent collection, I was not so long ago witness to an even worse outrage. Persons, including students and art critics, were stopped by another ill-trained or untrained, super-aggressive guard from using pens or pencils to write in their notebooks, because of some fancied threat to the pristine surfaces of the rather inconsequential art surrogates on display.

But it is not pencils and pens I am worried about. After all, you can always use the audio note-taking recorder on your iPhone. You may risk being looked down upon as someone -- no doubt a native New Yorker -- who habitually talks to himself in public. But we are used to that.

What I am worried about is the camera ban. I fear that panic-spreading, self-aggrandizing copyright lawyers and their paranoid clients have gotten the ears of museums, and, yes, even commercial galleries. Some artists, as you know, will not even allow images of their works on the internet, which results, of course, in zero Google-return and ultimately total invisibility. Doesn't everyone know by now that the more people who "steal" your images, the more famous you are?

Up the Ramp

Now that I have gotten that off my chest, I can confess that I thoroughly enjoyed Sehgal's "staged situation," This Progress, specifically commissioned for the Guggenheim. But first a caveat. If you want to convince everyone that what you are doing is totally, absolutely new, come up with a new name: not "event," "Happening," or "performance art." But what? "Staged situation"!

Sehgal also likes using the word this in titles. Some titles he has already used include This is new; This Success/This Failure; This is propaganda; This objective of that object.

What precedents are there for This Progress? For conversations or verbal exchanges positioned as artworks? Some have mentioned that conceptualist Lawrence Weiner offered conversations for a price long, long ago. Having conversed with Weiner for free, I certainly didn't fall for that one.

Since Sehgal's This Progress is thoroughly benign, I thought instead of James Lee Byars' question performance in 1968. He just sat there -- in the once-active exhibition room of the Architectural League -- attired in a red robe and his signature black hat, and answered questions. His answers were not particularly interesting, but the answers were really not the point, since the questions were not particularly interesting either.

But Sehgal is not the charismatic, Beuys-ian center of This Progress or any other This. By now -- thanks to the New York Times and other publicity vehicles -- you already know that you the visitor are greeted by a paid performer, who asks a question and engages you in conversation as you are tenderly guided up the ramp, then passed on to the next "trained participant." The latter is again a Sehgal term.

Although I am now contemplating calling myself an "art explainer" rather than "art critic" and relabeling my essays "art-awareness texts," the actual experience of Sehgal's brand-new "staged situation" was so fascinating that it was the first time I have ever progressed up the ramp all the way to the top. No matter what, I usually take the elevator and work my way down, adjusting to whatever chronological reversals that may entail.

As an art-explainer in disguise, my first encounter was with a very young girl who asked me what "progress" was. I answered that progress would be the elimination of hunger. So, of course, I went on to explain what I meant, and my explanation sort of flooded over into my next encounter, and the next.

Somewhere along the way in one of the pleasant conversations -- while strolling upward, ever upward -- I had to attack the idea of balance as a proper way to go about things and spouted the idea that there were some things that were good and some things bad; some things objectively true and some things objectively false. I did, however, successfully stymie my impulse to chat about art in terms of good and evil.

But I did rant against the stupid new New York Times category called "Room for Debate," often attached to topics where there really is no room for debate. The Times is not as bad as BBC News, which not so long ago asked in its "Have Your Say" section if Uganda should debate gay executions. Would we think it fair to allow Hitler to give his side of the "debate" about Jews?

My tour and my special version of Sehgal's artwork ended with a conversation with a Polish-born woman to whom I confessed I was Polish on my mother's side. And I found out from her -- for by now I was questioning as well as answering -- that her greatest relief in coming to the United States 40 years ago occurred when someone told her she no longer had to lie, as was necessary under the thumb of Russian-style Communism. Now, I am wondering if it were a lie of sorts that I did not confess that not only am I half-Polish, but am an art critic?

Of course I liked This Progress. It was all about me, and I am sure others had the same experience.

Progress Is a Comfortable Disease (e. e. cummings)

Sehgal's answers to questions once raised by the conceptualists before him are charming, but possibly disingenuous. Although I do not wholeheartedly agree with his answers, these are questions I enjoy.

I don't, however, think that Sehgal has made an advance over the conceptualists, as he seems to claim, just because he has no guilt about selling his artworks (no matter how weird the terms of exchange). He is right about one thing: the conceptualists, in spite of their youthful rebellion, went on to market every scrap of paper they ever marked and every bad photo they ever made.

Nevertheless, one suspects that if our art star of the moment -- he is even on the checklist of the Jeff Koons curatorial foray forthcoming at the New Museum ("Skin Fruit," opens March 4) -- continues the trajectory of his blossoming career, somewhere, somehow, someone will offer scripts and other material manifestations of his eventlike, Happening-drenched "staged situations." And even photographs of them.

And what about his other strictures? No opening receptions, no wall texts, no catalogues. This is progress? I would ban illiterate and irrelevant wall texts and catalogues, for sure. Now if only young Sehgal could add no press, no photographs of the artist, no profits, he would really be saying something new, even though we would probably never hear of him again.

FOR PAST ENTRIES GO TO "ABOUT THIS ENTRY" AT THE RIGHT, CLICK ON "ARCHIVES." SCROLL DOWN FOR ENTRY TITLES.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT WITH EACH NEW ESSAY, PLEASE REQUEST BY NOTIFYING: perreault@aol.com

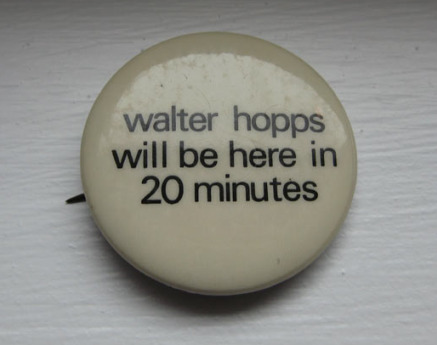

Historic button produced by employees of the Corcoran Museum in D.C. when the "elusive" Walter Hopps, once an art dealer, was director; now reproduced to celebrate the publication of Hans Ulrich Obrist's History of Curating.

Moving From the Dark Side

New York art dealer Jeffrey Deitch will be the new director of L.A.'s Museum of Contemporary Art. Certain NYC art galleries -- but definitely not Deitch Projects --are perceived as offering better exhibitions than many museums. Perhaps we should pause and compare art museums and commercial art galleries or, to put it another way, the for-profit and the non-profit spheres.

The art dogma is that these should be as separate as Church and State, which is what we believe in the USA, right?

Art museums are tax exempt, considered to be charities operated for the public good. Because donations may be deducted, more or less, from taxable income, museums are government-supported sub rosa. This indirect support far outweighs any direct support, unlike in Europe.

It is generally supposed this legerdemain was instituted because of a lack of interest on the part of the American public in the arts and a presumed outrage if direct funding were set in place. What? Money for men in tights? For screeching sopranos? For the preservation and public display of paintings that only the rich admire? For marble carvings of naked ladies? For Shakespeare, when vaudeville is so much better?

No, the reasons are not historically clear. Consider that as part of the City Beautiful movement in the 19th century, local governments gave land for temples of culture like the Metropolitan Museum in New York and removed those acres and the consequent structures from the tax roles. There is no record of riots in the streets when this happened.

A more persuasive theory is that an indirect method of arts support prevented government say-so in programming, perhaps a justifiable fear considering the so-called Cultural Wars that ensued in the last century.

Charitable Deductions

Preferential tax treatment of expenditures or gifts to organizations that the law qualifies as having a socially beneficial characteristic and for which the donor is not motivated by direct benefit when making the contribution.

Since 1917, individual federal taxpayers have been allowed to deduct gifts to charitable and certain other nonprofit organizations. Such organizations (hereafter called "charitable") were already exempt from the income tax. A charitable deduction extended the benefits of exemption to individual taxpayers, so that income donated to charitable organizations was exempted from all levels of income taxation.

The deduction was intended to subsidize the activities of private organizations that provide viable alternatives to direct government programs. The 1917 law increased tax rates, and the deduction was introduced to alleviate congressional concern that the higher tax rates would discourage private charity (Wallace and Fisher 1977). To control the revenue loss, total charitable deductions were limited to 15 percent of taxable income. Corporations were first allowed a deduction in 1935.

From The Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy by William C. Randolph

Galleries are run for profit. Museums technically are not, but since government support, unlike in Europe, is wanting -- and getting more so -- non-profit art venues such as museums pretty much have to be self-sustaining through fundraising, the largess of trustees, and corporate sponsorships. Admission fees do not cover very much. Hence we have fundraising events, and the ceaseless sucking up to the rich and the courtship of corporate sponsors.

Oh, yes, did I forget to mention that the tax-policy ploy is paid for by a tradeoff?

Staff and trustees are not allowed to use their positions in non-profits for personal gain. But gains can be subtle and difficult to track or catch.

You would not want a CEO of even a major corporation if he (or she) were a total Art Babbitt, worried about whether or not a bicycle wheel attached to a stool was art. In any case, why would anyone give so much money and time if not really interested in art? The period of Old Money sense-of-duty is long gone. It seems that if you are art-interested, it is almost inevitable you are going to be self-interested. Not only does one hand scratch the other; your left hand scratches itself.

What if the principle of full disclosure were made law? That all trustees and staff (certainly directors and curators) must publicly list the art they own? Is transparency enough? Who would read those lists? Lists alone will not stop conflict of interest and potential gain on the back of the taxpayers who do not make charitable deductions.

A museum exhibition usually increases the value of the art in the exhibition and all other art by the artist. I assume that this is why galleries and collectors are more than helpful to museums. I am told that galleries often pick up packing and shipping costs and subsidize catalogues. And sometimes collectors do the same.

Walter Hopps.

More...

Deitch is not the first art dealer, by the way, to switch sides. In 1962, Walter Hopps left the Ferus Gallery, which he co-founded and co-owned, to become the director of the Pasadena Museum of Art, where he presented the first museum retrospectives of Kurt Schwitters, Joseph Cornell, and Marcel Duchamp (!), as well as the first Pop Art survey.

As fate would have it, Franklin Parrish Gallery recently offered "Ferus Gallery Greatest Hits Volume I" (723 N. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles) documenting the gallery founded by Hopps, Ed Kienholz, and Irving Blum. Andy Warhol's first solo (32 Campbell soup cans) was not the only memorable exhibition. Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Larry Bell, Ken Price, Ellsworth Kelly, Josef Albers, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and Frank Stella showed there too..

Alas, no such stellar list for Deitch, who now, like our sainted Hopps, enters the nonprofit whirl with no experience in same. Yes, Deitch backed Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, but since then his gallery extravaganzas, to be kind, have been recherché. He is, of course, ceasing his business operations now.

Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art

You Will Never Work in This Town Again

What really is creepy, however, is that Eli Broad -- who recently rescued MOCA from oblivion with a big chunk of cash -- and who, apparently not satisfied with having the Broad Contemporary Art Museum of LACMA under his belt, is now dickering with various political entities in the region to donate a site for his own stand-alone museum. Broad is not only a lifetime trustee of MOCA, but also of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

He is also a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a regent of the Smithsonian Institutions.

How did all this happen? Well, Mr. Broad certainly is rich. He discovered that one could make and sell houses without basements. And then he went into the retirement-savings business selling his company in 1999 to AIG (the company too big to fail) for $18 billion. Broad is not as rich as Bill Gates or Mike Bloomberg, but he and his wife are big-time collectors of contemporary art.

Sounds like the ideal trustee: wealthy and loves art.

As L.A.'s self-appointed art mogul, in the interest of transparency and to avoid conflict of interest, just like Deitch, Eli Broad should declare all of his holdings. He already has. One list of artists in his collection includes all the usual suspects in a sort of "one chip on every square" strategy. Also on the Broad Art Foundtion website are artworks on loan to LACMA's Broad Contemporary Art Museum. Sounds like he is lending his collection to himself.

Broad is filling a leadership vacuum. Are there no other players to step up to the plate? How embarrassing for Los Angeles, for California, for art.

Hero or Clown?

Above is a video of Mr. Broad announcing Deitch's selection, courtesy of L.A.'s ever rambunctious Coagula magazine. (The captions are theirs, not mine.) Note that "Barnum" Broad claims, rather outrageously, that MOCA will continue to be the leading contemporary art museum in the world. Yeah, and it nearly tanked.

True. Chicago's MCA has only 2500 objects, compared to MOCA's 5000. Beyond this association, such a statement is apples to oranges. TATE Modern and MoMA collect contemporary as well as modern art. How does MOCA's 5000 compare to these? More important, how will Deitch as director care for MOCA's collection, since he has no experience in this regard? A collection is what makes a museum a museum and not a Kunsthalle like New York's New Museum or P.S. 1 or almost any ICA in America.

More amusing and certainly more scary is this music video tribute to Broad, (This Is My Circus) produced by L. A. County Museum, directed by Mike Binder, and choreographed by Ben Wolf.

Paradoxes and Conundrums

Paradoxes and conundrums are the stuff of life. A world without contradictions, overstatements, sins of omission, collusion, bargaining, and wheeling-dealing is a world without air. If everything were rational, we would die of asphyxiation. A world without wiggle-room is a world without surprise.

For instance, to avoid all conflict of interest we would have to forbid non-profit trustees (and directors and curators) and their mates, spawn, mistresses, and all kin from owning any art.

We want trustees who are passionately interested in art. For directors we want the same. However, it is unlikely that those who are passionate about art will not own or ever want to own art. Nor is it likely that they will not be socially or otherwise engaged with other art lovers.

Since conflict of interest is so likely and transparency is the ideal, those in the know "recuse" themselves -- I love that term -- when potential conflicts arise, like approving an acquisition or an exhibition. I may refrain from voting or even leave the room, but this only underlines the location of my heart and/or my wallet.

Should we, out of fear of "rocking the boat" -- even when the boat is sinking --- take a vow of silence?

Now we come to a deep paradox:

Publicly identified art dealers are not allowed on non-profit boards. It just wouldn't look good. It would give the show away.

You can trade in art as a high-stakes hobby or addiction, but as long as you don't hang the art-dealer shingle, you pass muster.

Checks and balances? Don't know of any.

Yes, we must have transparency. Yes, we must recuse ourselves. Wink, wink. But to what effect?

The Pledge of Allegiance to Art

I recently saw the raucous, pre-Code movie Night Nurse (1931). Before they have to tangle with Clark Gable's evil chauffeur, Barbara Stanwyck and Joan Blondell, as new nurses, are seen taking off their clothes, jumping into bed with each other in their slips, but eventually they recite the Florence Nightingale Pledge. Forbidden to embed, so here is link instead. The Pledge is half way through clip. Enjoy.

Since an art pledge might be called for, here is the Artopia version of the Nightingale Pledge, for use by museum trustees, directors, and curators:

I solemnly pledge myself before Art and presence of this assembly;

To pass my life in purity and to practice my servicesto art faithfully.

I will abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous

and will not take profits, perks, or favors nor knowingly administrate any unnecessary exhibitions nor aidin the accession of

dubious, trivial, or inconsequential artworks.

I will do all in my power to maintainand elevate the standards of art

and will hold in confidence all personal matters

committed to my keeping

and family affairs coming to my knowledge in the practice ofmy calling.

With loyalty will I endeavor to aid the museum in its work,

and devote myself to the preservation of the artcommitted to its care.

.

Deitch Projects, in Soho, NYC.

Keep the Faith!

If moving from the dark side of art commerce to the heaven of art museums is as rare as it appears, why the hue and cry about the appointment of poor Mr. Deitch, and not that of Bill Moggridge, the new director of the Smithsonian's Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum? Moggridge served on the Cooper-Hewitt board and is credited as the inventor of the laptop, but he has no museum credentials.

As Andy Warhol once quipped, "Art is business." Yes, indeed. So we may want business types to manage museums, which can be as complicated and as difficult to steer as large corporations. But why not industrial designers or even artists?

But because there is something deeper at stake, selecting Deitch as director of an art musuem -- even though he may be the only one foolish enough to chance such a perilous appointment -- is dangerous. He may be genial, but I call his appointment the Lifitng of the Veil.

It should be obvious from what is outlined above that what separates art from business -- otherwise known as the Dark Side -- is not a firewall but a veil. The veil has been rent. But do we really want to find out the truth about the Wizard of Oz?

When Hopps moved over from the Dark side, the museum world had not become as rigidly professional as it is now or quite as openly compormised by corporate and collector interests -- the latter probably ineveitable given current budgets and ambtions. Arts dollars feed the economy, but you have to spend money to make money.

No one anymore wants to think of art as a religon. (Or at least not since Oscar Wilde.) But art is indeed a belief system. When that belief system is compromised, the cathedral falls.

What are the articles of faith?

The appreciation of art is the appreciation of the human spirit.

The creation of art is above commerce.

Art is worth more than its cash value.

Art is knowledge and self-knowledge.

Art is truth, not merchandise.

Art is not a circus.

The Biltmore Solution

As galleries take on the function of mounting temorary exhibitions, museums will be left to preserve art and show only their collections for educatinal purposes rather than entertainment. We then await something new and vital.

The museum without walls or halls?

The museum without borders?

The totally digital museum?

But how about the for-profit museum?

In the footsteps of P.T. Barnum's museum rather than the elitist cabinet of curiosities -- the two-headed origin of American museums -- the profitable museum may again have its day.

When I was director of the Newhouse Galleries at Snug Harbor on Staten Island in the '80s, I knew about the Biltmore manse in North Carolina. George Washington Vanderbilt built it in1895; it has a modest 250 rooms and paintings by Sargent and Whistler; now on a mere 8000 acres, it is still the largest private home in this country. Of course, it is no longer just a home, but an historic house museum. However, it is not operated as a non-profit, but a for-profit, subject to all appropriate taxation and exempt from none. It is entirely self-sustaining, thanks to the stewardship of G.W. Vanderbilt's great-great grandson, Bill Cecil.

Back then, just for fun, and because I was weary of and wary of the constant grant-applications I had to write to keep my contemporary art program (including outdoor sculpture) afloat, I tried to figure out what admission fee we would need to charge in order to be independent of any government or corporate largesse.

Although I probably should have included the equivalent of rent and utilities that Snug Harbor -- founded in 1822 as a nicely endowed retirement home, but saved from destruction at last -- might have charged, I divided my annual budget for the visual arts department by the number of visitors and arrived at $28 per person.

Would a paying public come up with that amount to see a stained-glass window that reads "Sailors' Snug Harbor -- For Aged, Decrepit And Worn-out Sailors," a dome decorated with nautical motifs, Thomas Melville's office (which was then mine), and exhibitions of emerging artists?

The North Carolina Biltmore charges $40 per person in the winter and $60 the rest of the year. In comparison: MoMA is $20; the Whitney, usually $18; Guggenheim, $18; LACMA, $12. LA MOCA, $10. Furthermore, if you want a guided tour of the Biltmore, add $17. (The Premium Tour is $150.) And if you drive there, which is likely, valet parking is another $15. After you add restaurants, gift shops, a vineyard, and other moneymakers, the Biltmore is self-sustaining and has enough income to conserve keep up all of its many rooms, buildings, and decorative and fine art treasures.

Is this nod to the past the wave of the future?

Damien Hirst: Golden Calf. Reportedly sold at the all-Hirst Sotheby's auction in September 2008 for $186,000,000. Is this artwork satirical or a case of having your calf and eating it?

Art Will Survive The Museums

On top of inheriting a shaky enterprise, everything Deitch does will be examined in the light of his past as an art dealer and secondary-market salesman. Perhaps L.A. now has the museum director it deserves. We really hope he will rise to the occasion.

And the occasion is more than a local quagmire of bad karma, bad leadership, bad positioning. It is the quagmire of art museums in general.

Not a day goes by without mention in the media of art facsimiles and fakes and/or the difficulties of presenting and storing or restoring art. Aren't digital images easier to handle? As venues for new art or even historical exhibitions, museums are well on their way to becoming merely income-generating tourist sites, luring the paying customers to see the one and only really-real, two-headed monkey. Or the Golden Calf.

P.T. Barnum's American Museum, 1841-1865.

* * *

For your enlightenment and/or amusement:

ART DUMP: ART STARS DUMP MISTAKES

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/jan/28/michael-landy-art-rubbish-dump

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/jan/28/michael-landy-art-rubbish-dump

MORAL RIGHTS: MASS MOCA CAN'T SHOW UNFINISHED INSTALLATION BY CHRISTOPHE BUCHEL

MORAL RIGHTS: MASS MOCA CAN'T SHOW UNFINISHED INSTALLATION BY CHRISTOPHE BUCHEL

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/29/arts/design/29artist.html

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY: CONTACT perreault@aol.com