main: July 2008 Archives

Paul McCarthy: Bang Bang Room, 1992.

Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Sheldan Collins

Disorientations

Who is Paul McCarthy? Not having the good grace to simmer down like a few other once-sensational artists I will not deign to name, McCarthy has never gone away, never graduated to the curious art Valhalla comprising those who are still here but gone. Or, alternatively, those gone but still here.

In short, professor McCarthy, who has taught art at UCLA since 1982, continues to annoy, and in the process resists either art-rag or art-establishment packaging. A West Coast rather than an East Coast favorite, he is neither the last of the Destruction Artists nor the first of the shamans. "Paul McCarthy: Central Symmetrical Rotation Movement" at the Whitney until Oct. 12 offers up a disconcerting chunk of his sometimes clownish but almost always provocative/evocative anti-art displays. His 2001 New Museum extravaganza was nearly destroyed by faint praise. His most disconcerting works - e.g. a performance involving sticking a Barbie doll into his rectum or the 2007 Santa Clause with a Buttplug inflatable --- are nowhere to be seen. Someone is cleaning up his act.

Nevertheless, even Whitney curator Chrissie Isles when she tries to confront the pared down McCarthy can't quite pin him down. In her catalogue essay, she traces McCarthy's work to the influence of Destruction Artists such as Ralph Ortiz and Hermann Nitsch, but then connects him to everyone under the flag of darkness, from Francis Bacon to Vito Acconci. Isles does her best to weave all available references and citations together in a critical fiction that almost reaches coherence, yet still misses the convulsive nature of McCarthy's art. Convulsive art deserves a convulsive text. If it can still be said that there are Dionysian and Apollonian extremities of the art spectrum, McCarthy belongs with those of the Dionysian persuasion.

And, of course, he is uneven. We no longer like artists who are even, never venturing out of their brand look, never wavering. That was so '60s, so Donald Judd -- whose work was unbelievably elegant but ultimately corporate. Alas, sometimes corporate is best. Frank Stella, venturing from his pin-stripe paintings, took one giant step to the protractor paintings and then fell further and further off the map with every banal shaped canvas and every unspeakable sculpture he came up with.

But even in the tightly curated McCarthy selection now at the Whitney, there is too much. I would have eliminated Spinning Room (conceived 1979, created 2008) with all of its moving projections. It achieves a kind of dizzy spectacle, but does not have the visceral impact of the other two large pieces: Bang Bang Room (1992) and Mad Room (1999/2008).

Both are kinetic rooms, full scale. They are one-part amusement park and one-part Dante's Inferno brought up to date, an unstable mix not previously achieved by any artist I know.

Bang Bang Room is composed of four hinged walls forming a square, each wall pierced by a door at it center. When this machine is at rest, you are free to walk on the platform within. And then the motors start, the walls flap open, as do the doors -- which then bang shut with a sound like a rifle shot, again and again, or like a body falling out of an airplane and landing on a tin roof.

When I first walked into the big and partially mirrorized third floor space, I saw/heard the Bang Bang Room loudly banging, doors and walls opening and closing. The question to myself was not what the hell is this, but what hell is this?

As the mechanism came to a halt, coward that I am, I did not venture onto the platform. I certainly didn't want to be caught inside. Have viewers been caught, or do the guards shoo them away before the timer kicks in? Even watching from the outside, you get the feeling of being trapped by housing, by domesticity, by art.

Mad Room spins, but spins in a variety of ways. A chair that could be an electric chair or a chair used to subdue a maniac or a murder suspect or a caught spy/secret agent or a plague carrier spins inside ... a spinning room. Sometimes chair and room spinning at different speeds spin in opposite directions but all speeds and speed and direction changes coming far too fast and far too furiously for comfort so that you may have to check yourself check yourself to make sure you yourself are not spinning too and your head is spinning and then it spins off into space and you are strapped to the chair in some other universe that is beyond art where you are trapped until the damned diabolical machine turns off.

Nearby is a photo of the artist with his arms outstretched. That image stands for his 1979 performance called Spinning. It almost has as many semantic and expressive layers as another Doc Art piece nearby: The Veil (1970), identified as "photograph of a mirror through a veil." The artist took it of himself in a mirror, covered from his head almost to his knees with a large gauzy veil: portrait of the artist as ectoplasm.

Do you remember spinning around and around as a child until it seemed as if you had left your body? Wasn't there something sexual going on? Correct me if I am wrong. Looking at Mad Room and Bang Bang Room gave me a similar experience, except the propulsion comes with a big dose of horror. The loud noise of those walls and doors flapping open and banging shut is disturbing enough. I had the feeling that Bang Bang Room was exorcizing some hideous domestic demon; whereas Mad Room was summoning up a demon of an even more horrifying sort. This is not art; it's exorcism.

Paul McCarthy: Mad House, 1999/2008

Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Seldan Collins

* * *

Eliasson Falls

Art is not a contest. Or is it?

No critic can write about everything and always has to pick and choose, so underneath each byline there are always winners and implied losers -- the latter overwhelmingly outnumbering the former. Or sometimes we spoilsports just have to go on record to contradict the hype.

When I finally saw some of Olafur Eliasson's East River waterfalls, I thought them more impressive than most of his work at MoMA and P.S. 1, which is not saying much (see: Artopia review).

Because of its site beneath the iconic Brooklyn Bridge, that particular incarnation of Eliasson's free-standing waterfall idea works best. It also has high visibility from the Lower Manhattan shoreline. You can see it beautifully from the tip of the South Street Seaport pier. It is a strange and unseemly (therefore poetic) presence. Now only if he had limited himself to this one peak moment. But, no. In the world of almosts, one spectacular artwork is never enough.

* * *

Bourgeois Fails

Then I turned my laserlike, razorlike gaze to the needlessly gargantuan Louise Bourgeois exhibition at the Guggenheim: hundreds of works up and down the spiral, adding up to ... ? Well, there are several good pieces: the totemic Personnages (1947-1951), the many-legged The Blind Leading the Blind (1947-49) and certainly the truly creepy Spider Couple of 2003. But otherwise, haven't we seen enough of her half-baked Surrealism to last the rest of our lives? She had a MoMA retrospective in 1982 and represented the U.S. in the Venice Biennale of 1993, with a large exhibition of work at the Brooklyn Museum ("The Locus of Memory") that same year. Add a few diamond necklaces, and the celebrated "nests" would be perfect Late Surrealist window displays.

FOR AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERTS: perreault@aol.com.

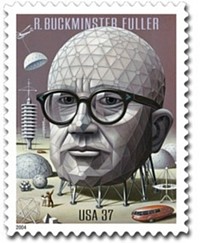

Debunking Uncle Bucky

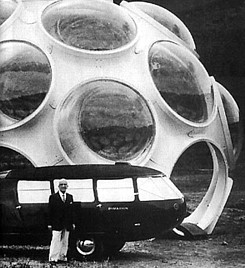

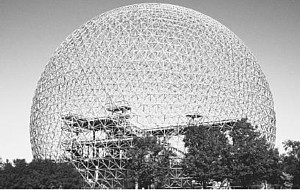

Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983) invented the geodesic dome, sort of. He was not the first to use the icosahedron for construction. Walter Bauersfield in 1922 in Jena, Germany built a planetarium that had suspiciously geodesic aspects.

Moral: Whatever it is, if you do not give it a name and publicize it, it is not yours.

Artist Kenneth Snelson, a student of Fuller's at Black Mountain College, made the first "tensegrity" structure, in which metal poles that did not touch are suspended by wires. Fuller thought up the term and took full credit for the innovation.

Moral: If you claim it and name it, it's yours.

* * *

In honor of "Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe" (Whitney Museum, through Sept. 21), here are some additional factettes:

Margaret Fuller, transcendentalist and early feminist, was Fuller's great aunt.

As a student, he was thrown out of Yale twice.

Our Uncle Bucky - everyone called him Bucky -- believed that meat was the best way for us earthlings to get good nutrition, and for long periods of time he ate only steak, prunes, Jell-O and strong tea three or four times a day.

He made a habit of napping for 30 minutes after every six hours of work, falling asleep instantly.

That Uncle Bucky managed to overturn his sleek, three-wheeled Dymaxion car is not noted in his 45-ton "chronofile" or in any public statements and writings. Nor was it ever revealed that, although parallel parking was a snap, moving out from the curb required backing up into traffic.

The 3,500 standing orders for Uncle Bucky's 1946 Dymaxion Dwelling Machine or Wichita House miraculously morphed in one of his interminable lectures into 35,000.

Vis-à-vis the DDM, he claimed the motorized accordion doors not only took up less space, but also "reduced the spread of germs by doorknob contact."

He often called architects "exterior decorators."

Our Uncle Bucky - beloved by John Cage and other luminaries - was not modest: "I have discovered the coordinates of Universe."

He also rewrote the Lord's Prayer, claiming that his version offered direct proof of God's existence and ... "constitutes a scientifically meticulous, direct-experience-based proof of God."

Oh god, our father -

our further

our evolutionary integrity unfolder

who art in heaven--

who are in he-even

who is in everyone

hallowed (halo-ed)

be thy name

(be thine identity)

halo-ed......

But he also said: "The next most dangerous thing to the atomic bomb is organized religion."

Our Uncle Bucky believed that the decline of the traditional family and the apparent increase of homosexuality and bisexuality were merely the result of a reduction in the need for the species to reproduce.

On the other hand, Bucky, obviously not a Darwinian, believed humans "arrived from elsewhere in Universe as complete human beings." To clarify: "Man as prime organizing/ 'Principle' construct pattern integrity/ Was radiated here from the stars--Not as primal cell, but as/ A fully articulated high order being."

Pictures From a Lecture

Pictures From a Lecture

I was once persuaded to attend one of Uncle Bucky's marathon lectures. How could I not have been intrigued? I thought the Dymaxion Car and then the Geodesic Dome at Expo 67 in Montreal were swell, in a Popular Mechanics kind of way. Bouncing around the stage, as advised by his dancer daughter, Bucky seemed more Barnum than beatific, more gasbag than gallant. Blather by any other name is still blather. Baloney is baloney. He gave a new meaning to Wall-of-Sound. I stuck it out for two hours and, deciding it was double-talk, and headed home to Hegel.

I have nothing against free association (surprise!) but Bucky, in spite of his free-verse "poems," was not a poet. He merely broke up prose with poetrylike line breaks. Here is a quote at random from his Untitled Epic Poem on the History of Industrialization:

The post-graduate M. A.s - Ph.D.s, Engineers,

and Science Docs of all kindsnow outnumber two fold

the American Expeditionary Forces of 1917.

All three major strands

are now being braided into cables,

into fatigueless, non-crystallizing

infinitely flexible cables

of the invisible suspension bridge

of the mind

between man and his destiny

high over the waters of exploitable matter

save over the Hell Gate of political doubt.

What? Could you play that again?

Oh, yes. Now I get it. Artopia likes the braiding, but dislikes "the Hell Gate of political doubt," whatever that is.

But then again, Intuition, another book-length "poem," less full of filler, boasts a reproduction of a handwritten text from Ezra Pound on the frontispiece: To: Buckminster Fuller/friend of the universe/bringer of happiness /liberator./with affectionate admiration/ Ezra Pound/Spoleto/June 29th 1971.

And what exactly was Pound autographing? A copy of The Cantos? Or perhaps a soiled napkin?

Oracularmaniacal Neologistics?

Oracularmaniacal Neologistics?

A sure sign of the unhinged, along with unusual capitalization and hyphenating, is the invention of new terms and made-up words to cover data or meanings already adequately answered for by existing words and phrases.

Neologisms can make you see things in a different light, but they can also cloud the brain, puff-up the inventor, and gain credit where credit may not be due. Neologisms can make something not-so-new or not-so-complicated seem newly discovered and wonderfully complex.

I am not talking about puns or comic turns, as in Lewis Carroll or Gilbert and Sullivan. I do not mean witty portmanteau words, such as Carroll's snark. I am referring to what can only be called Fullerisms.

"Mind wind," dreamed up by Fuller, is supposed to mean the feeling of "imminentness" when an idea is in the air. Or does it really mean mental flatulence and/or hot air?

"Allspace Filling"? Here is Bucky's definition in Synergetics, a tome perpetuated in 1975. It not only illustrates the way his mind worked (or, I fear, did not work), but also his turgid way of writing and, alas, his public speaking, both of which could be characterized as persiflage or persiflogical:

"... The multiply [adverb] furnished but thought-integrated complex called space by humans occurs only as a consequence of the imaginatively recallable consideration of an insideness-and-outsideness-defining array of contiguously occurring and consciously experienced time-energy event."

Huh?

But how can you hate someone who actually coined the word debunk (in 1927) and came up with "Obnoxico" as his very own imaginary multinational corporate nemesis?

I am not sure that allows us to forgive his grandest invented word synergetics, born of a forced marriage between "synergy" and "energetic." It means, according to Fuller, "the performance of the whole unpredicted by an examination of the parts or a subassembly of the parts." The word synergetics sounds meaningful, but the meaning doesn't. It would be a great name for an oil company.

Nor should we excuse him for the silliness of "ignore-ance." Or for using "ephemeralization" when he really meant "dematerialization" or perhaps -- in his own words, "not less is more, but more with less."

The helpful Whitney handout bravely offers definitions of Fullerisms such as "Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Science," "Lightful" and "Octet Truss." But please note that the subtitle of the exhibition places the article "the" in front of "Universe," whereas Uncle Bucky always insisted upon "Universe," capitalized and article-free.

Buckminster Fuller, that geomanic geocentric, believed (1) that the tetrahedron could solve all problems and (2) that the earth really is the center of Universe. He was an industrialistic engineerist who was mathemaniacally geometristic.

He was ultimately globalistic, understanding that we are passengers on (his term!) Space Ship Earth, but blind to how to dispose of those doing the steering. He was the Pied Piper in a business suit. He was, in the name of the greatest good, an elf infected with predictomania and oracularitis. He was infected by neologorrhea, demonstrating that made-up words and new meanings forced upon old words can create another reality you might want to invest in, but not necessarily one you could trust.

* * *

Dome Mystic

So what on Earth are we to do with Buckminster Fuller? The exhibition at the Whitney made me rethink Fuller's place, his accomplishment, and his total nuttiness. Do we forgive him his eccentricities (perhaps insanities) because he came up with the geodesic dome, which has had some practical applications? Do his 20th-century proverbs compensate for the swill of his eight-hour lectures and his Synergistics tome?

What was disarming about Fuller was his optimism and his idealism, however misplaced. He really seemed to believe that technology, specifically his version of same, would save the world. Progress was not only possible, but inevitable. Toward that end, unlike the dropouts constructing geodesic "drop cities" out of recycled materials, he had no qualms about dealing with governments of all stripes or with any willing corporate bigwig. Progress, he believed, would be top-down. His notion of autonomous housing, each unit producing its own energy through wind-driven turbines, predicted ideal off-grid lifestyles -- still obtainable, alas, only by elite minorities. But his attempts at mass-produced housing show at least that his heart was in the right place, if not his brain.

The closest we have come to mass-produced housing nowadays is the MacMansion: too large and too costly, suggesting Mr. Blanding's Dream House on steroids, duplicated into infinity and arranged tightly packed to form gated "communities."

Fuller himself might have had more luck if he had pointed to the Airstream trailer rather than his own engineering.

Oh, no, he had to predict high-tech igloos delivered by military helicopters or revolving aluminum nests perched on poles. The problem with those kinds of "practical" housing is that they don't film very well. What movie star - and we all see ourselves as such - would want to live in a hut? Even one made of aluminum?

You can't film actors and actresses taking sponge baths in broom closets.

Fuller seems to have been looking a little too hard at airplanes. Although you can make a dramatic airplane exit by walking down those retractable steps onto the tarmac, you cannot make an entrance by entering one. There is no foyer, no nightclub platform from which to descend. There's no room inside for a camera crew. And where in any aluminum yurt is there privacy?

I am not qualified to judge if Fuller's geocalia is correct. For all I know, 60 degrees, as he claimed, and not 90 may be indeed the basic angle of Universe. In any case, in terms of geodesic domes, I imagine it is difficult to place paintings, mirrors, video monitors, or bookcases on a concave, faceted wall.

Most people don't want a space that's created by a leaky, echoic, floor-to-ceiling dome. If forced to give up flat walls, they'd rather camp out in a tent. Or a sleeping bag under the stars.

But at least our Bucky tried. Tried to see beyond the tried and true. Tried to seek out logical first principles. Tried to solve the problems generated by pseudo-scarcity, bad design, abuse of resources and bad faith. In some ways he was fearless. He was not afraid of appearing foolish. Perhaps he was so self-centered that any vision of his own foolishness never entered his head. Perhaps he was blessed...with naiveté. He was an Artopian ahead of his time.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT FOR NEW ENTRIES

CONTACT: perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog