main: June 2008 Archives

Father's Day 2008

Majid Majidi's The Willow Tree (2004) is an art-house tearjerker about answered prayers. A blind man is able to see. As a crowd of well-wishers throws flowers to greet our newly sighted Professor Youssef at the Tehran airport, the camera lingers briefly on his wife's face as she hopes he will find her appealing. But she discovers, of course, that he cannot even recognize her, which is an amazing feat of acting and/or directing. That is one of the many variations on the meanings of seeing and not seeing. And, oh yes, the professor teaches the works of Rumi, the great Persian saint/poet.

Willow is an allegory. Not a shot is wasted, not a metaphor avoided. Ambiguity is embraced -- standing for what cannot be said, or seen? The camera's eye becomes your ears and the tips of your fingers.

So, although Majidi is in many ways a conventional director, I had to see what films of his were in stock at Kim's, my amazing neighborhood video/DVD rental outlet. It was Father's Day and, as fate would have it, I grabbed The Color of Paradise (1999), a kind of prequel to Willow, and reportedly the largest grossing Iranian film in the U.S. It tracks the sad and transcendent tale of a blind boy named Mohammad who, like the professor in Willow, walks carefully, very carefully, lifting each leg by the knee, gently placing down each foot as if he were about to go over a cliff. Fingers are antennae.

Paradise is full of cinematic synesthesia; not only are we aware of frail Mohammad's world of sounds and moving air, we see him (he is precocious and might grow up to be a professor of literature specializing in Rumi) reading small portions of the world, bits of texture, running his fingers over stones and leaves as if the world were Braille. Which of course it is (if you are Baudelaire or Rimbaud). And when he hears geese, he asks what they are saying to each other. Everything is in code.

Majid Majidi: The Color of Paradise, 1999 (publicity still)

In many ways, whether or not Majidi is part of the Iranian New Wave or, as some blind film critics assert, the Iranian Disney, The Color of Paradise is the perfect Father's Day movie, an antidote to that sentimental holiday, seemingly created by or for the greeting-card industry soon after the creation of Mother's Day early in the last century.

Mohammad's poor, bedraggled, ice-cold, single-parent dad spends most of the movie trying to get rid of his son. Mohammad will not support him in his old age; Mohammad might stand in the way of a new, possibly financially rewarding marriage.

Happy Father's Day.

More Male Art

Chris Burden's What My Father Got Me is a 65-foot-high monument to fatherhood and the Erector Set, a tower/building constructed of enlarged Erector Set parts, based on the first G. S. Gilbert module girders. It sits until July 19 at the Fifth Avenue entrance to Rockefeller Plaza. If you plant yourself in front of it in a certain way and if you are my height and pretend you are a camera, you can spy Paul Manship's golden, art deco Prometheus through the girders. Or do you still prefer Jeff Koons' Flower Puppy, once placed behind and above Prometheus?

Every male of a certain age will know what an Erector Set is. It came in a bright red-metal "briefcase." Inside, a pamphlet gave easy-to-follow instructions for all the bridges, buildings, and Ferris wheels you might want to make out of the pint-size girders and the tiny nuts and bolts. I have yet to see any evidence that anyone, man or boy, ever made anything not in the pamphlet, such as a Batman and Robin or a collie.

Do I have to say it? "Erector" has a semantic and, more importantly, an oneiric relationship to "erection," as in an erect penis. Was there ever a more Freudian boy's toy?

Oddly enough, I had no interest in the Erector Set my father bought me. I assume it was the gift he had wanted when he was a boy and/or the All-American product he thought would make a man of a son who was more interested in dreaming up costume dramas for anyone nutty enough to want to cavort in crepe-paper capes.

I wouldn't go near the Lilliputian girders.

Dad was clearly disappointed in my lack of interest, but happily -- almost too happily -- stepped in to spend hours building a tabletop, motorized Ferris wheel. Later, no one had the nerve - neither my mother who thought all toys were foolish nor my sister, who was still at the dolly stage - to dismantle my father's engineering triumph. Certainly not I; in fact, it was a relief not to have to deal with something so boring as linking girders with tiny nuts and bolts. The Ferris wheel had fortunately used up all the supplies.

For my birthday, I announced, I wanted a chemistry set.

That put my poor Dad at ease. He probably was afraid I would ask for a sewing machine or a paint-by-number kit. He sprung for the Gilbert chemistry set, and hid it in the attic. I knew exactly where it was, but I waited patiently for August 26 to come around. By then, fortunately Daddy had shipped out again: he was a cook on a supply ship on its way to Africa, suffering, I later discovered, from acute sea-sickness. So much for my fancied Viking roots in Brittany. Vikings do not get seasick.

I don't think my father ever found out there were only two things I wanted to make with the chemistry set: explosives and perfume. I certainly didn't mention it when we spoke on short-wave radio. Neither bombs nor perfume were included in its pamphlet, but I did manage to have some fun putting matches to magnesium. And I did make a bomb of sorts that left the devilish sulfuric odor of rotten eggs.

Alas, although I thought I could make perfume by boiling roses or steeping them in alcohol, neither process really worked. Besides, where was I going to get my hands on musk or priceless ambergris? I was fascinated by ambergris, particularly when I read that it was really whale phlegm. I did have hopes of finding some nearby on the Belmar, New Jersey beach. If others had found Nazi mines washed ashore and Japanese balloons that had reached the California coastline, then anything was possible.

The Art of Being Famous

If you know about contemporary art, then you must know Chris Burden. A latecomer by a few minutes to the Body Art thing and the Scandal Ploy -- succeeding Bruce Nauman, who was in turn succeeded by Vito Acconci - Burden achieved notoriety (1) for having himself shot in the arm and (2) for getting nailed to the hood of a Volkswagen.

Chris Burden: Shoot (1971)

Burden: Tans-fixed (1974)

As it happens, yours truly spent a week with Mr. Burden and a few other art stars on the Micronesian island of Ponape in 1979. This art spree was in celebration of - and produced by -- a small but very smart art operation on the West Coast called Crown Point Press. Burden, unlike John Cage, Pat Steir, Robert Kushner, Laurie Anderson and most of the other artists (all of whom had made prints for Crown Point) didn't say much. He was almost as silent as William T. Wiley, but without the lean demeanor and California-cowboy aura.

We were also, I think, celebrating the forthcoming decade. And the artists had to sing for their suppers by forecasting what was going to happen in the '80s. No one predicted the rambunctious commercialization of art or the so-called return to painting, which, in the greater scheme of things, lasted a New York minute.

Ponape, by the way, has mysterious ruins, "temples" and "canals" seemingly constructed of basalt logs.

In the evenings, after the artist presentations and flown-in beefsteak dinners, we traversed the passageway beneath the dining-room deck. The passageway was jammed with hundreds of outsize, croaking frogs.

Composer John Cage had brought his own brown rice in little plastic bags, and the previous cook, fed up with such things as those beefsteak airlifts, left for the island of Truk and then abandoned Truk for Saipan, in search of a South Pacific untouched by luxurious scuba-diver compounds.

Our grass huts, complete with mildew-resistant water beds, were arrayed on the slope of what looked like a Hollywood back-lot lagoon. Some in our group also sampled a narcotic that the islanders made by chewing up the root of a certain native pepper plant and spitting out the juice; this phlegm broth was sipped for its numbing effect and hallucinogenic buzz.

But who needed hallucinations? One day, when we waded into the murky, lukewarm lagoon, I was unpleasantly surprised by a floor of living, slimy sea cucumbers. Another day, while tramping through the jungle, I came upon a shack, obviously occupied by a Catholic priest. The tangled sheets were still warm. Missionary? Anchorite? I never found out.

And whatever happened to Chris Burden?

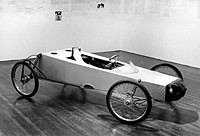

I really admired his 1975 B-Car:

"I set the goal of completing the car for two shows in Europe. I saw buidling the car as a means toward the end of driving it between galleries in Amsterdam and Paris as a performance. When I arrived in Amsterdam, I knew that the accomplishment of constructing the car had beome for me the essential expwrience. I had already realized the most elaborate fantasy of my life. Driving the car as a performance was not important after the ordeal of bringing it into existence." Chris Burden

And I fondly remember his 1990 Medusa's Head, a suspended globe encrusted with train sets.

Leading up to his hymn to the skyscraper, Burden has been building bridges out of these same stainless-steel versions of A. C. Gilbert's girders. He built a outsized model of New York's Hell Gate Bridge in 1998 and one of the Indo-china Bridge in 20002.

Now, of course, he is adored for the vintage streetlight collection permanently installed in front of the updated Los Angeles County Museum.

Now, of course, he is adored for the vintage streetlight collection permanently installed in front of the updated Los Angeles County Museum.

Infantilissmo?

Try as I may, although Burden has had many one-man exhibitions worldwide, I can't find any evidence of a retrospective. Or do we really need to go through the trouble of slam-bang, expensive extravaganzas when all we require is a website to show off the images? Art is all about images anyway. Or maybe about ideas. Surprisingly little art is better in real life than it is in a photograph.

When I teach contemporary art I usually mention my dream assignment: install an exhibition of known masterpieces in such a way that they all look awful. This has been done in real life by professionals, more times than I wish to say. The implication, which usually does not have to be spelled out, is that you can also show bad artworks in such a way that they will be mistaken for masterpieces. ?.

Next time around, if the art devil is ever allowed to teach again, I will actually make the assignment, but transfer it to using the camera.

That trickster Marcel Duchamp made sure that his last work was virtually unphotographable. At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, you have to look at his posthumous, allegorical tableau (Given: The Illuminating Gas...) through a peephole, thus changing it into a virtual photograph. Even if you had a real photograph of the full tableau -- the spread-eagled maiden, the hokey waterfall, etc. -- you would not be seeing the allegorical display through the peephole; the waterfall would not be "moving" like the image of water in a vintage beer sign.

On the other hand, without my camera and without actually visiting Rockefeller Center, would I have known that you could peer through What My Father Got Me and spy the Paul Manship nearly a block away?

If I hadn't been angling about with my camera, I would not have discovered the particular perspective that allows a comparison with the pointy penis of St. Patrick's.

Yet, as even my own snapshots prove, What My Father Got Me is certainly one of Burden's masterpieces. Can we now place him, along with Koons, in my new category of Infantilism (which could also be called Infantilissmo) and make him into yet another descendent of Claes Oldenburg? In regard to Burden's well-placed penis, if Neo-Pop it's not, then it's certainly Infantilissmo.

Yet, as even my own snapshots prove, What My Father Got Me is certainly one of Burden's masterpieces. Can we now place him, along with Koons, in my new category of Infantilism (which could also be called Infantilissmo) and make him into yet another descendent of Claes Oldenburg? In regard to Burden's well-placed penis, if Neo-Pop it's not, then it's certainly Infantilissmo.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA NEW ENTRY ALERT

EMAIL YOUR REQUEST TO perreault@aol.com

Olafur Eliasson: Ventilator, 1997

For weeks now my Eliasson Problem has loomed. MoMA and its satellite P.S.1 ---- the annexation is complete; founder Alanna Heiss has been retired -- devote so much real estate to the work of this Icelandic Dane that every art critic worth his or her bile must weigh in.

I was predisposed to liking work purported to be Minimal, spiritual, nature-loving, color-delving, light-obsessed. And certainly (with some rather raggedy exceptions) if not anti-object, at least product-neutral. And, as constant readers may know, I love everything Icelandic. Well, I probably will not like Alcoa's aluminum smelting complex. Ore is shipped in from abroad then processed, using Iceland's cheap, geothermal-derived energy. That which drives the smelting is what keeps the winter sidewalks ice-free. The slightly sulfuric hot water from below the rugged landscape heats all of indoors, including greenhouses, and the sidewalks of Reykjavik, so there is no danger of slipping when you are gazing up at the Northern Lights.

I don't know why I continue to be fascinated by heating where no heating has been before. Once, when I was stationed in an art museum in a certain gloomy city in upstate New York, I was amazed that the elegant assistant director, even in the dead of winter, arrived without a coat. Sturdy stock, I thought. She was not a native, but born and bred in the Brooklyn. I lived closer to the museum in a high-rise and had resorted to using ice clamps on my boots in order to brave my treacherous route across a wind-swept plaza of solid ice.

But in truth, my mentor's suburban kitchen opened directly on to her heated garage with its remote-controlled roll-up door; and, of course, the driveway was kept clear of ice by radiant heat coils inside the paving. And then on to the museum's underground parking.

The exotic is closer than you think.

But where else except Iceland could there be a national referendum concerning the rental of the national gene pool for scientific purposes? I think it was perfectly all right for Iceland to offer up its meticulous genealogy for genetic research. As might be expected in a country where your father's first name makes up the first part of your last name, record-keeping has always been essential. My name would be the equivalent of John Jean's Son. And get this: girls get their mother's names. And then too the gene pool itself, I've read, is remarkably pure: modern day Icelanders are descended from Vikings and their Irish slaves. Earlier than the Vikings, there were Irish anchorites, but of course they did not reproduce. And that's pretty much it.

According to poet W. H. Auden, Hitler sent spies to confirm Icelandic racial purity; he needed more Siegfrieds for his Master Race. The spies reported a high-percentage of tall and good-looking blonds, but unfortunately Icelanders were incorrigible drunks. You may not know this, but the national Icelandic drink is potato-derived, cumin-flavored brennivin, also known as The Black Death.

All of this windswept wind-up is for nought, because for all practical purposes Eliasson is more Danish than Icelandic; although he was born in Iceland and offers a series of landscape photographs of my beloved island, he grew up in Denmark. Denmark! Iceland was a Danish colony for over 300 years.

* * *

Eliasson's "Take your time" (through June 30 at the Museum of Modern Art and P.S. 1) gobbles up space. At MoMA in particular I felt I was in some time-warp. I was visiting enlarged versions of some of the trippy, kinetic light-works favored by the Howard Wise Gallery in its heyday in the late '60s. Or was I being bathed in disco décor?

Surely a hallway bathed in noxious yellow light turns everyone into zombies, but it also reveals --- accidentally - one of MoMA's design flaws. Too much precious space is gulped up by crowd control and getting viewers from one place to another. The artist's yellowing of that hallway reveals its true size. I am sometimes annoyed by the Metropolitan Museum's warren of little interlocking galleries or by the Guggenheim slope, but MoMA feels like a World's Fair pavilion awaiting the entire population of Minneapolis all at once. In the public areas, I would wager almost half the space is geared to people-moving (or in the lobby, people-waiting). Surely, thanks to Eliasson, I will never love yellow again.

On the other hand, Eliasson's 1997 Ventilator installed in the Atrium is the best use ever of that really ungainly space: a single, self-propelled electric fan swings on its electric cord back and forth, seemingly at random, seemingly dangerously just above visitors' heads. Otherwise, there is so little to view in the various Eliasson lighting displays and mirror tricks that you look desperately for something to see. The art tourists themselves, front and center, are not in themselves interesting, either. They are grim and respectful, wearing their next-best clothes, just short of attending a wedding or a funeral.

Searching for something to look at, you notice that the restroom signage includes an icon labeled Baby Change, tinged yellow by the spill from the yellow hallway. Is this where you can exchange your baby? Or is it where you can turn your toddler in and get a basketful of smaller infants? And inside the men's, the commodes are labeled Toto. But I was definitely not in Oz, in spite of the buzz. I was in installation hell.

Is Ventilator Eliasson's only credible work?

* * *

A similar effect haunts P.S. 1. The funky charm - more and more smoothed over since the MoMA takeover - sticks out under Eliasson's lightworks. One piece I actually liked, one that lived up to some of the curatorial claims. Alas, The natural light setup, 2008, was punctured by anomalies: a hump of pipes that looked like Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's God of 1913; a sealed electric socket, and a small door like a line drawing with visible hinges and no knob. This is in an all-white room where the light from the flawlessly covered ceiling changes slowly in brightness, perhaps from dawn to dusk and back again. The lesson here is that minimal is not easy; emptiness qua emptiness has to be perfect. If the artist is not after emptiness, however, then I am not interested.

The good thing is that P.S. 1 was parceled Beauty (1993), a kind of rainbow within a proscenium and the 1998 Reversed waterfall, which is placed in the grotto that opens from the first floor to the basement.

And the eye-catcher-that-everybody-loves? Well, let's put it this way: Take your time (2008) -- which gives the exhibition its title -- uses a gigantic, revolving mirror on the ceiling of the biggest of the exhibition rooms on the 3rd floor. It is less boring than watching paint dry, but not by much. With the exception of the gridded landscape photographs (I do love Iceland), everything else is kind of a waste of time. Worst choices: The poorly made spheres and other paraphernalia that clutter the rooms flanking Take your time. Just because P.S. 1 is an old schoolhouse doesn't mean we need to be lulled by science projects. Art is about alchemy, not astronomy. Art is about LIGHT, not light.

So the Eliasson Problem is this: What do you do with an obviously talented but totally uneven artist? Hey, even Picasso produced a lot of junk. Most artists need editing.

If the exhibition consisted of fewer works, we would have had something worth talking about. Instead, what we need to talk about is how the curators (Madeleine Grynsztejn, formerly of SFMoMA and now the director of Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art, and Roxana Marcoci and Klaus Biesenbach at MoMA) put together this disappointing survey. It may be that some of Eliasson's best works are not transportable or impossible to recreate, so we can only hope that the artist will survive this listless extravaganza and that his forthcoming East River project - New York City Waterfalls -- will be so wonderful that his reputation will be revived.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT WITH EACH NEW ENTRY, E-MAIL YOUR REQUEST TO PERREAULT@AOL.COM

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog