main: August 2007 Archives

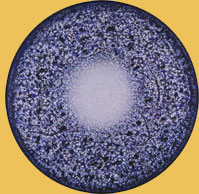

Richard Pousette-Dart (1916-1992) Lost in the Beginnings of Infinity, 1991. Acrylic on linen, diameter 72 inches. Private collection, Vienna

© Richard Pousette-Dart by ARS, New York, 2007

The Final Cut

Editing as authoring -- one of my themes today -- is not a rehash of Roland Barthes' death-of-the-author. The author may have been misplaced, but he or she is still alive and not just a mask for a group of anonymous meddlers or the imperatives of cultural context. Excuse me for being old-fashioned, but when editing is so extensive and immoral that it is collaborating or co-authoring, texts so wounded must bear the editor's name as well as the pro-forma author's. Editors, particularly those who are ghost writers of one sort or another, must be forced out of the closet, must be held accountable.

Novelist Thomas Wolfe was really Wolfe and Maxwell Perkins. Or was Thomas Wolfe only the public, publicity face of editor and rewrite-man Perkins? O Lost (the original text of Look Homeward, Angel is now in print. LINK Did Perkins improve the text? Could anybody have improved this purple prose? What we really need is transparency.

Authors -- they do indeed exist -- may need some friendly advice or, as they like to say in journalistic quarters, a safety net. We don't want spelling mistakes or lawsuits. We don't want to be embarrassed by too much originality or creativity -- or in Wolfe's case too much lush description, too much "literature," neither of which, by the way, are to my taste.

In Artopia we aim for what might be called an internal dialectic. Count the themes. Enumerate the contradictions. Unveil the layers. Annotate the braids and spirals.

Luckily, the Artopia safety net is managed by my domestic partner, who is widely appreciated as one of the world's most author-friendly editors. Perhaps his sympathetic editing comes about because he is a talented writer himself. But elsewhere, outside of Artopia, one should be so lucky.

I will not bore you with the horror stories I can recount about my experiences -- and those of my colleagues --- at the hands of enemy editors. In some sense the death of the author has been cinched, but not in the manner Foucault imagined. Just check out any of the art magazines. Multiple edits, a house "style" (which always means lack of style) and even quick changes without the author's approval appears to be the rule -- although in some magazines there seems to be time to insert alien opinions.

On the other hand, as a magazine editor myself, I have seen the scraps some noted authors turn in. Editing, in these cases, is not rewriting, but writing. All the publication is paying for is the so-called author's name.

Actually, we writers do indeed collaborate with both colleagues and enemies. We write for actual and imagined friends. We answer fools and idiots, most often denying them credit or credence by keeping their vile identities under wraps. We best the enemies we never have met and who are dead or yet to be born. Not even poetry comes out of the blue.

Metaphorically, the art world has written me. This phrase sounds good, but we must never confuse the euphonious paradox with truth. Only bad poets and post-structuralists are allowed to do that.

Jack Kerouac reading his poems...

Who Wrote On the Road?

My themes are inspired by a constellation of events: 1) Viking's release of a paginated print edition of the original scroll of Jack Kerouac's On the Road, 2) the Richard Pousette-Dart exhibition at the Guggenheim New York flagship from August 17 to September 25, and 3) my own 1967 ARTnews piece on Pousette-Dart.

When On the Road came out in 1957, the literary establishment trashed it. The rest of us were inspired to hit the road. In 1961, by the time poet Joe Ceravolo and I reconnoitered in San Francisco, he had already hitchhiked from New York to Mexico and then up the West Coast. Less reckless, I suffered the Greyhound route. Didn't we already love Charlie Parker? Didn't we already hate the New Yorker and New Criticism? It turns out that On the Road , with its unorthodox narrative, energy and antiheroes (whom we all suspected were thinly disguised real-life "characters"), and not the suburbiana of John Updike, became the true American classic.

Yet how much better is the newly published, original manuscript than the final cut. The language is fresh and still has an avant-garde edge. That edge, over the course of the seven years it took to get it published, was aggressively dulled. Was the makeover strictly for ease of publication? If the higher-ups at Viking were worried about lawsuits, name changes would have sufficed. Maybe in 1957, a long, unparagraphed text was deemed unreadable. But was the rushing, breathing, caffeinated text on the original scroll, typed out in three weeks in 1951, more difficult than James Joyce's Ulysses, then the certain badge of true literary genius? I don't think so.

But now, of course, we Artopians have taken delight in such nonparagraphed wonders as Austrian Thomas Bernhard's typically nasty, but somehow thrilling, Yes or the Hungarian Laszlo Krasznahorkai's masterful Melancholy of Resistance. The latter, even better, is composed of one very, very long sentence. Talk about a run-on!

I discovered Melancholy not because of Susan Sontag's back-cover blurb, but because this was the book that inspired director Bela Tarr's brilliant, seven-hour Satan's Tango. Tarr is the master of the slow and deadpan pan and the long, long take. A 10-minute pan across a Hungarian field? You feel the mud on your feet and in your nose. And then later, through a window you can watch drunken peasants dancing in real time, during the last days of their collective farm. I found Tarr because he influenced Gus Van Sant's LINKGerry, another foray into deadpan single takes.

Some of the restructuring and rewriting of On the Road was the author's own doing. Kerouac was desperate to have his beatnik instruction-manual published. His friends William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, who figure in his book, were already on the road to fame. But who was our Jack listening to? Why did he add adjectives? When he delivered his manuscript to Viking Press in the form of a roll of paper under his arm, he declared he did not want a single comma changed because it had been dictated by the Holy Ghost.

The print version, enshrined in the male dorm rooms of America, is slightly more pedestrian than vehicular, more pompous than pugnacious. The original is more like what On the Road was cranked up to be.

I do not have the patience to compare both texts line by line. Just let me say that now I want to read the posthumous Vision of Cody, built around excised chunks of the original On the Road, but also incorporating Kerouac's verbal sketching-from-life device.

In the meantime, here is a telling demonstration of editing, reconstructed by Howard Cunnell in his introductory essay to On the Road: The Original Scroll (Viking ). It shows the kind of damage done so long ago by Viking editor Helen Taylor. Her "corrections" are in brackets:

They rushed down the street together[,] digging everything in the early way they had[,] which has later now become [which later became] so much sadder and perceptive and blank[. B] but then they danced down the street like dingledodies[,] and I shambled after as usual ["as usual" crossed out] as I have been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time...

Read both versions aloud. One is grammatically "correct," and the other is art. The run-on windup for "the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk..." pushes this often quoted phrase over the top into jazz. How stiff the schoolmarm, tone-deaf, Viking version is.

But didn't Updike and all his ilk get rewritten at the New Yorker? Maybe that is what has always been wrong with Updike. Well, there is always the stupidity of his dreary subject matter. We wanted literature and we got Updike. We wanted greatness and we got Philip Roth. We wanted the Kerouac that Ginsberg loved, but instead we got a new meaning for Taylorism.

By the way, when can we expect a DVD and/or online version of the taped-together, handmade, foolscap scroll, so we can read it the way our Cousin Jack actually wrote it -- which is like a vertical version of a biblical scroll or, preternaturally, like a rather long blog?

Nina Leen, The Iracibles, 1951. Photograph (Life Magazine)...

Pousette-Dart, Unedited

Curating, which is the art of selecting from finalized artworks, is also a kind of editing. Although sometimes a curse, it can also be a kindness. Time now proves that Franz Kline's dealer, Martha Jackson, was right in refusing to show his full-color abstractions. Nevertheless, many curatorial mistakes have been made, and we have a duty to look at things more than once. Or twice.

Richard Pousette-Dart (1916-1992) just won't go away, but it is not only the current show at the Guggenheim that needs editing, it's the whole career. Pousette-Dart is a painter I have long admired. But he was painfully uneven. The curator of record here is Philip Rylands, director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, who has opted for an ordinary précis of the twists and turns that Pousette-Dart left behind.

Was it that Pousette-Dart did not avail himself of Clement Greenberg's advice, that art-bully's editing? Many did, and they can be said to have made their paintings in collaboration with their favorite art critic. I have often noted that Greenberg LINK to old Blog is the greatest unacknowledged artist of the '50s and '60s. Not because of his own pathetic watercolor nudes, but because he edited so many paintings before they left the studios of the artists of record. Masking tape was Greenberg's paintbrush. The tape told the artist where to cut the canvas. Greenberg was also infallible when it came to deciding which end was up.

Did Pousette-Dart move out of New York City too soon? Was it that he had mystical aspirations? That he also wrote credible poems?

I am also puzzled that the exhibition is "organized in collaboration with the estate of the artist, the artist's widow Evelyn Pousette-Dart, and with the support of the American Contemporary Art Gallery, Munich." My italics.

I suppose it is better that all cards are on the table (in this case, on the Guggenheim website). Perhaps it is a question of semantics. Is "support" different from "collaboration"?

Exhibitions are expensive. But which exhibitions in museums have been subsidized by art dealers or the artists themselves? As it turns out, many are supported indirectly, and some directly. Over at the Whitney, for example (as is customary in all museums), it is perfectly clear from the labels beneath the outsized paintings that you can buy a Rudolph Stingel from the Paula Cooper Gallery. So while the party lasts, please stand in line.

Transparency is better than subterfuge, right? Read those wall texts; read those labels!

If Pousette-Dart exhibition is a fair sampling of kinds of paintings the artist made over the years, which I think it is, then we have a problem. Did he have no self-curating ability, no critical sense? Once he breaks out of Picasso-influence, he gets even more uneven. I still think that his apprenticeship pieces are as good as the early work of Pollock or de Kooning, but probably not better than their efforts at catching up, as I asserted in my ARTnews piece in 1967.

Where was my safety net then? If I remember correctly, someone -- Thomas Hess, John Ashbery? -- took out the Pousette-Dart poems I had included, but no one stopped me from extravagant praise. When hired by editor-in-chief Hess (a well-known critic and curator himself), I was warned that artists did not like to be compared to other artists. Even favorably? I guess favorable comparisons were OK, but poetry was not.

But there it is in black-and-white: I nailed the artist's mystical side, probably forever relegating him to the minor leagues. No one then even whispered about Pollock's high-school fascination with Theosophy, Ad Reinhardt's love of Zen, or Barnett Newman's Kaballah fix. Hess later went on to emphasis Newman's debt to Jewish mysticism when he wrote about that artist's "Stations of the Cross." And for this he took a lot of flack.

Pousette-Dart was one of The Irascibles. He signed Barney's letter to the New York Times protesting the idiocy of the Metropolitan's 1950 contemporary art show, which was definitely unsympathetic to what would soon be called Abstract Expressionism. Fifteen of the signatories made it into Nina Leen's famous 1951 photo in Life magazine: Theodoros Stamos, Jimmy Ernst, Newman, James Brooks, Mark Rothko, Pousette-Dart, William Baziotes, Pollock, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, Bradley Walker Tomlin, de Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, Reinhardt, Hedda Sterne. Students everywhere should memorize this list.

Only Tomlin and Sterne, the one woman in that photo, are now less famous than Pousette-Dart. Well maybe Pousette-Dart is more famous than Stamos and Brooks and Baziotes. After all, his son Jon is the Pousette-Dart of the Pousette-Dart Band.

For some reason, Pousette-Dart pére couldn't quite package himself; he seems to have had the crazy idea that each painting was an adventure, which is a recipe for failure. The odd thing is that his allover paintings, most of which have a mystical aura, are his most successful. These are the paintings that even Greenberg, who was decidedly antimystical, should have liked, strictly on formal grounds. That the extremely formal and the mystical should so dramatically coincide contains a lesson of some sort, but one I will leave for another time.

Near the end of his career, Pousette-Dart tended to use the thick black lines he began with, but now made by stippled impasto. To suggest stained glass? To effect a synthesis that would also include his love of writing and hieroglyphics? Oh, I hope not. I think it was Light he was after. His best paintings are Light objectified. The dark side of insisting that art is a process, not a product, is that sometimes you get stuck with a less than perfect result. What we need is a skillfully edited Pousette-Dart. Next time around, only the allover "mystical" works, please.

Pousette-Dart, Night Landscape, 1969-7. © Richard Pousette-Dart by ARS, New York, 2007

A Kink in Time

I remembered I had written about Pousette-Dart before. So after a long search through my unseemly archives, I found the November 1967 ARTnews. My article was called "Yankee Vedanta," probably titled by the executive editor, poet John Ashbery (who was also one of my poetry mentors). The title was pulled from my text:

Richard Pousette-Dart is an impassioned pacifist, a vegetarian and a poet, filling numerous notebooks through the years with poems, notes, speculations about painting as a spiritual process and, though he professes no specific religion (his religious thought might be called Yankee Vedanta), his writings are filled with unapologetic references to God. A less fashionable sensibility is hard to imagine.

Of course, he was showing at the Betty Parsons Gallery, which had been the home of Newman, Pollock, and Reinhardt. The elegant Mrs. Parsons had spiritual interests of her own, which I happened to share. But here I edit myself, because I would prefer to write of her sexuality than her spiritual discipline. Suffice it to say, she once played tennis with Greta Garbo, and writer Patricia Highsmith was a buddy.

I cannot find my original Pousette-Dart manuscript, probably typed on horrid, non-acid-free yellow foolscap, so I can't tell if the Basic English (my fabulous unedited sentence quoted above notwithstanding) was mine or the result of heavy-handed Elements of Style editing. Other articles, such as Louis Finkelstein on de Kooning, Rackstraw Downes on Neil Welliver, and Al Brunelle on Kenneth Noland's horizontal-stripe paintings were slightly more dense. But I was a novice.

For your amusement, please note that the cover price of ARTnews then was all of $1.25. (This was, believe it or not, the Artforum of its time.) The full-color cover is a detail from Benjamin West's Death of Gen. Wolfe, 1770. The first three pages have full-page ads for Liquitex, Christie's ("Fine Pictures by Old Masters") and Aquatec; the back cover was an ad for Grumbacher paints. Obviously, advertisers knew or were led to believe that ARTnews was read by a large number of working artists.

Even in 1967 there were discreetly placed but timely ads from galleries whose artists were anointed by articles in the same issue. (But not by the some would say too proper Betty Parsons.) Which came first, the ads or the articles? Well, the exposure afforded by a magazine article should at least be thanked. And an ad is always the best way.

Elizabeth Baker, now editor-in-chief of Art in America, was then ARTnews managing editor. Among the editorial associates (i.e., reviewers) were names you might recognize: Scott Burton (who became a sculptor), Suzi Gablick (an artist who was then in the process of becoming a critic), Kim Levin, who later became one of my successors at the Village Voice, and Marcia Tucker, who evolved into a Whitney curator and then went on to found the New Museum. Editor's Letters include: "Ad Reinhardt, a solitary thinker and mystic. A salutary influence in the art world. His passing has created a void for those who knew him. Rollin Crampton, Woodstock, N.Y. (Yes, there was a Woodstock before the Woodstock of 1969 virtually wiped out that upstate haven's venerable position as a summer art colony.)

The Reviews and Previews were assigned at $4 each: Robert Mangold, Marisol, Jules Olitski, Mark Tobey, but mostly dozens and dozens of artists now lost both to art history and the art market. Some texts are a solid paragraph and others a single Zen sentence or two like: X..."paints pictures over the mantel: Mediterranean village, creamy New York skyline, a host of golden daffodils. His woodcuts too are attractive." Or the really, really negative: Y..."offers nudes, landscapes, river scenes of gold and pink cast." All and all, 82 pages of edited texts, but unedited nostalgia. Articles paid $150, which covered three month's rent for my tiny apartment in the Village, Greenwich Village. The East Village had not yet yet been invented by the realtors.

AND

Thinking of braids, Artopia recommends the following:

Wenda Gu's braided hair pieces at Dartmouth College LINK, described in Grace Glueck's N.Y. Times Review and showcased in the accompanying slideshow LINK.

The giant braid of Tunga's At The Light of Both Worlds, first shown at the Louvre, but now at P.S. 1. This is an image of it when it was at the Louvre:

And, last but not least, John Perreault's "The Braid: A New Paradigm for Art" in the online journal theartsection LINK.Go to archive: Vol.1, No.3 (Aug.07).

For an Automatic Artopia Alert for new entries, please e-mail: perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog