main: March 2006 Archives

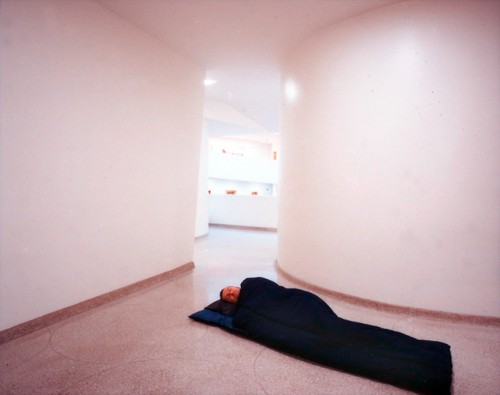

Dean MacGregor: Sleeping Project (at the Guggenheim), 2005

Call It Sleep

Add up the hours of sleep. That's a lot of down time. Or is it? Healing, sorting, rebuilding those synapses. Getting ready to roll. I think I'll take a nap.

And dreams, those letters that demand interpretation also need to be counted. Of course, sleep itself is a symbol.

Sleep as an art subject is rare, but Dean MacGregor may win the prize. As part of an ongoing series of sleepovers, on October 27, 2005 -- as recently reported on Artnet -- MacGregor slept all night in the Guggenheim Museum. Photo evidence of the Guggenheim nap and snoozes at other sites can be seen on his website: deanmacgregor.com

* * *

Yes, Scott Burton did it first. Well, sort of. At a dinner party last month, Art in America's Betsy Baker asked me, vis a vis MacGregor, when Scott (a mutual friend) had done his sleeping piece.

As part of the opening night reception of Street Works at the Architectural League of New York in 1969, Burton, clad in pajamas, slept on a coton a staircase landing. Where's the proof? Back then we did not think of photographing every single art work we made, every single thought. How do you photograph a thought?

That was to come later.

Since we had had a falling out over something or another --- probably his capitulation to what I thought of asobject-mongering --- I never got a chance to ask Burton if he had indeed dreamed that evening, surrounded by strangers trudging up and down the elegant stairs of that Upper East Side mansion.

Sleepers Awake

It's unlikely MacGregor knows of Burton's sleep piece. He would have mentioned it on his website, where he cites the obscure Christopher D'arcangelo who in the mid-70's "did an action in the Guggenheim without anyone's permission or help." D'arcangelo also: "...cut all the number 13's out of a book, 'The exorcism of the number 13'."

Besides, Burton's sleep piece was in public and was singular, whereas MacGregor's are mostly out-of-sight (but not off-camera) and compose a whole series of events. Dreams are not even considered, at least consciously.

MacGregor's art space sleepovers are particularly gripping, for who has not in moments of weakness in museums wished for a nap - out of sheer eye-fatigue or, more likely, boredom? The Stendahl Syndrome that apparently plagued Victorian visitors to Italy who swooned from aesthetic overload is no longer rampant. We have seen all these images before. An exit poll would I am sure reveal that most museum visitors actually had been asleep while standing and walking through the hallowed halls of MoMA, the Met, the Whitney, or scooting down the Guggenheim spiral. This leads to the metaphysical proposition that we are all asleep, pretty much most of the time.

What makes MacGregor's sleep pieces worth calling to your attention and worth thinking about? They carry forward certain tendencies of art radicalism explored in the late '60s but abandoned, repressed, co-opted, subsumed. Distribution seems to be mainly through his website. The sleeping pieces reactivate private performance conveyed/communicated by photography, such as the Body Works created by Ana Mendieta in the Seventies. They are symbols and thus richer, more complicated, more meaningful than signs or straight-forward figures of speech.

I dreamed I was in the Guggenheim Museum.

I dreamed I was in MoMA.

I dreamed I was in the Gagosian Gallery in Beijing.( No, no, not that, please.)

MacGregor's sleepover relates to Abramovic's recreation of famous art performances of the past, also recently at the Guggenheim. We are beginning to look at conceptual performance again. Further evidence is the number of academic requests I get for period information. It has really become a nuisance; so I usually say read Artopia or read my book (a book not yet published, not yet written).

Why didn't the much vaunted dematerialization of art stick beyond the mid-Seventies? Too many artists have this strange notion that they deserve to make a living from their art. And we do like things: tangible, tactile, weighty, gorgeous, expensive and, we hope, profitable things. Furthermore, how will artworks be saved for future generations if they are "worthless," that is, cannot be bought and have no cash value?

On the other hand, MacGregor claims on is website that "The sleeping project is not a 'photo project.' It is not to be thought of in a particular category, i.e. performance, conceptual, institutional critique. It is about thinking."

If it were more clearly an institutional critiques would he been allowed to sleep at the Guggenheim, L. A. C. M. A., and other institutions?

So far MacGregor or surrogates Paul Griffith and Tobias Wong have slept in art galleries, museums, a castle, a magazine office, academic offices, and another artist's apartment. Come to think of it I am not sure any of the sleepers are actually MacGregor. I'd prefer that all of them were, but that doesn't seem to be his mission. For all I know the guys in the various sleeping bags may be faking. I demand to see the R. E. M. and brainwave records. Well, not really; it is the idea that counts. Or is it the image?

Perhaps none of the above, or, as MacGregor writes: "There is a danger of oversimplifying, or pigeonholing, or reducing, of defining artificial boundaries, when facing a movement of thought that constantly evolves so as deliberately to defeat and baffle all preordained categories."

In the meantime just bear in mind that no matter who you are with or where you are, when you fall asleep you sleep alone. Simultaneous dreaming only takes place when you are awake. It's called politics or everyday life. As far as I know, there are no documented examples of two or more sleepers having the same dream at the same time, but, no doubt, informed Artopians will ply me with examples.

* * *

F.Y.I. Here's an album of sleep images:

John William Waterhouse, Sleep and His Half Brother Death (1874).

Henry Fuseli: The Nightmare (1781).

Anne-Louis Girode de Roucy-Troison: The Sleep of Endymion (1793). Studied with Jacques-Louis David; won Prix de Rome in 1789. In 1812 he "inherited a fortune and thereafter devoted himself to writing unreadably boring poems on aesthetics."

Paul Gaugin: Spirit of the Dead (1892).

Frederic Lord Leighton, Flaming June (1895)

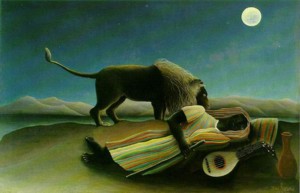

Henri Rousseau, Sleeping Gypsy (1897).

Constantine Brancusi: Sleeping Muse, (1910)

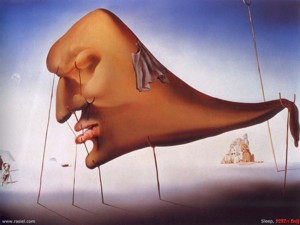

Salvador Dali: Sleep (1937).

TO RECEIVE ARTOPIA ALERTS WHEN NEW ENTRIES ARE POSTED, CONTACT ME AT PERREAULT@AOL.COM.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog