main: February 2006 Archives

Andrea Zittel: Escape Vehicle

"Sometimes if you can't change a situation, you just have to change the way you think about a situation."

The Things I Know for Sure, Andrea Zittel.

'Please Do Not Touch or Enter Artwork' (Sign at the New Museum)

A-Z Administrative Services,Andrea Zittel'scorporate "identity," equals assumptions-must-always-be-challenged. A naïve definition of art insists that it must be divorced from use. The aesthetic, a term first used mid-18th century, is seen as opposed to the utilitarian. On the other hand, any serious look at art history, preferablyglobal -- but even a limited Western survey -- will produce a majority of artworks that have served some purpose along with visual delectation: practical, religious, political or even educational. Ranking objects by or through function is power- and class-based. Is art used as religious or corporate propaganda -- or investment -- automatically better than art you might eat off or sit on? To put a finer edge on the no longer viable debate, what we really need to know is that the aesthetic and utilitarian are not mutually exclusive characteristics or functions of art. Even in the last century,as the Arts and Crafts Movement evolved into Bauhaus and Constructivist imperatives (and then into we now call design), the utilitarian was not entirely excluded from the modernist canon. Do we not honor Gerrit Rietveld? Le Corbusier? Charles and Ray Eames? And Isamu Noguchi wearing his design hat? Was it such a large step for Scott Burton to propose sculpture as furniture?

Burton is the immediate precedent for Zittel, whose first "comprehensive survey" is now at the New Museum/Chelsea, (556 West 22nd Street, to May 27). I guess we are no longer allowed to say "retrospective" for a survey of work by an artist under 90. Zittel was born in 1965. The superstition (de Kooning had it) that takes the form of the curse-of-the-retrospective can be expressed as: once they see what you have been up to, it's all over -- the "they" meaning critics, collectors, and other artists. Zittel need not worry (although I don't think exhibition terminology is one of her concerns). She equips herself well. Unlike too many artists who have had "surveys" and after showing their true colors tank, Zittel looks better here than in any single gallery show of hers you may have seen. Is it editing or timing?

Cautionary tales about inflated reputations can be assembled at will. Suffice it to say that even critics and curators fade. But, in Teddy Roosevelt's famous phrase, let's not go there.

Dangers abound.

Enough art has already been destroyed by "theory" and covert commercial or academic agendas.

Fairness requires me (I don't know why) to mention that not everyone is interested in the same set of problems, so it would be foolish for me to proclaim that high seriousness is demonstrated only by a passion for the interstitial. Zittel, however,embodies the interstitial, for the body of her work is both sculpture and design. Otherwise, what would anyone make of her huts, warrens, and dresses? She is a borderland case. From the wilderness of Williamsburg to the wilderness of the California desert, she has persistently experimented with living.

Ghosts of design icons haunt her production: the Eames Case Study House No.8; Constructivist fashion; Mondrian's boxy, ad hoc furniture he made for himself when he lived in New York.

Housing is clearly one of Zittel's subjects. First, her redo of her tiny Williamsburg studio; then A-Z Living Units (1993-94), A-Z Cellular Compartment Units, and now the Joshua Tree Desert A-Z Homestead Units. All respond to declining housing space. The solution? Live in a trailer-inspired housing unit, costumized, if possible. The Homestead Units, however, are not so much based on the trailer as on the tool shed; the smallest construction that in most places does not require special building permits and approvals.

Zittel: A-Z Living

The Long, Long Trailer (Lucy and Desi Hit the Road)

I-pod housing has happened before: trailers. I have always loved trailers. The art critic Lawrence Alloway announced that his ideal home was a well-designed yacht, everything built-in, everything with a place and everything in its place. I prefer the ideal trailer. I once stayed in a restored 1949 Airstream in a trailer camp (emphasis on "camp") called Shady Dell in Bisbee, Arizona. A host of historic trailers can be rented by the night. I was in Airflow heaven -- literally, since Bisbee (where last year I gave a poetry reading) is 90 miles south of Tucson in the mile-high Mule Mountains. The ten trailers include an Airfloat, Royal Mansion, a Spartan, a Spartanette, and an El Rey. There's also a Chris Craft yacht.

Jeopardy strikes art in the form of classification systems, but one must persist. Zittel believes in rules-based behavior, particularly in art-making. Rules make you free -- but rules, I think, only of your own devising.When I was first teaching (it was at the University of Iowa back in the early '70s), I came armed with fresh slides of process, body and performance art and street works. I have since been told by someone who worked in the art department slide library then that I had created a behind-the-scenes ruckus because no one knew how to file my slides. They were certainly not slides of paintings or drawings, and they didn't look like any sculpture that had already been alphabetized by artist. So the librarians put them in a separate cabinet and were relieved when I retrieved them at the end of my semester as guest professor. It may be easier for the likes of Zittel now. Multiple categories can be the digital rule. I am annoyed by the New York Times online propensity to place the same headline in multiple categories, because it makes it seem there is more than there is. On the other hand, multicategorization is more than multiaccess. It is a corrective to the tyranny of the conventional. Clearly an examination of Zittel could comfortably fit under Fine Art, Design, Home, Architecture, and even (for recent efforts) Desert Living, if there were such a category.

Zittel: A-Z Homestead Units

Back to Basics

Kitchens, campers, bedrooms, and chamber pots have all been some of Zittel's choicest subjects. And clothing, too. The latter came about because, when employed as an art gallery attendant, she had to dress for the part, so she made her own clothes.

Laboratory-like explorations of nutrition add another level of research to A-Z Administrative Services. Yes, research. One way of looking at Zittel's productions is to see them as research projects for living; probes; efforts at deprogramming. Do we all need 2000 square feet of living space? Does anyone? Space greed is about prestige, not comfort. If you want breathing space, go outside (if there is an outside left). There is also something to be said for the nest, the cave, the cozy hideout in which you do not have to get up from bed every time you want a piece of toast or need to answer the door. Instead of receiving-room housing one could begin thinking of dressing-room houses. If space is at a premium, energy is at a premium too. Heating and cooling a closetlike, trailerlike pod is cheaper than heating and cooling a McMansion.

Madness can mimic Mamaroneck. Luxury condos in Chelsea are like McMansions in the sky. Although owning a gigantic loft and then buying a Zittel in which to live is my idea of luxury, I have to confess that a more practical, less sinful fantasy of mine is to live in an Airstream on any flatbed roof in the East Village. But why not buy an indoor parking lot in midtown and fill it withpermanently parked, vintage Airstreams for rent? Since I have been on an apartment quest recently, I can assure you that you would soon have a waiting list. You cannot believe the East Village rentals I have seen for $3000 a month, or, out of curiosity, the "furnished" rooms and shares you can see on craigslist.com for huge bucks. Hasn't anyone noticed that the world is truly overpopulated?

Now is the time to rethink comfort, family, crash-pad housing. We need I-Pod housing. We already have it! Zittel leads the way.

On average, more meals are eaten out or eaten inthe form of takeout than cooked and consumed at home. Do living quarters still need stoves and refrigerators? Zittel too is tied to the past, because even her most austere living spaces include hot plates. What's wrong with raw food or lukewarm takeout? Is there something dangerous about room temperature Diet Coke? Get rid of refrigeration!

Punishment in the future will not be prison-cell confinement. Cells will be too much like home, too cozy. Punishment will be other people.

Quaint, queer, quirky.

Zittel: A-Z Homestead Unit

Are We Free?

Revolutionary ways of day-to-day living already exist. The urban, global, digital nomad is not unknown. Dorm life conquers all. There are already shadows and shades living among us. In 1957 I shared a cold-water flat in Paterson, New Jersey, with two other poets. One was certifiable and the other was a Korean War veteran. He lived the life of what he called The Unit Man. He was a kind of criminal, but it took me a while to catch on. In any case, The Unit Man owned only what he could wear on his back, and everything else had to fit in one rather slim briefcase -- a volume of Dylan Thomas, a change of underwear and socks, a small notebook he called his Image Book for inscribing figures of speech and compound words that he thought would come in handy for writing poems. If you saw The Unit Man in the street you would think he was anIvy League Associate Professor of English Lit. He later took off for Mexico City, where his vices, which I leave to your imagination, could be practiced with impunity.

Solitary life is the wave of the future. The monk among us. The Unit Human holds his or her own against the onslaught of teeming or teaming populations, artworks, streaming media.

Tough trouble lies ahead.

Underground life becomes the norm. The Unit Human is hidden among a horde of robots. Suburbs become the noir cities they were made to replace, and the Unit Human is disguised as a housewife or a husband. Hello, Honey, I'm homeless.

Our new apartment in the Financial District (cheaper and better than anything we saw in the East Village, our sacred turf) insists on rugs and forbids waterbeds. We also had to sign a mold release, requiring we notify the management of any moisture.

VOLATILE.

Andrea Zittel: Clothing

What the World Needs Now

Wronged, the world fights back. Am I the only one who sees Armageddon when looking at images of Zittel's living units? This work -- please, Grace Glueck -- is not whimsical. What on earth is whimsical about costumed hikes? Dressing up is the most important part of sports.Instead, Zittel offers....

X-ray visions of global-warmingdesertification. And opportunities for other artists to experiment with homebuilding. Because I will be teaching a seminar at the Phoenix Museum of Art next month, I'll be spending some time in someone's pool house in Paradise Valley. I love the desert, but it really needs to be air-conditioned, doesn't it? It was so dry this past summer that out on Long Island, where I sometime hide out, I actually saw and heard a woodpecker pecking at the dead, bone-dry lawn. Tap-tap, tap-tap. And now in New York we had the biggest snowstorm ever.

You are where you sleep.

Zittel, who deftly combines Dada and design, entering through the right end of what was conceptual art and Scott Burtonism (furniture as minimal sculpture), exits art into life, with, I think, real thoughts on sculpture, art, and life.

Andrea Zittel: Chamber Pot

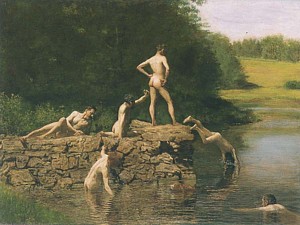

Thomas Eakins, Swimming, 1883-1885

Thomas Eakins: Untitled Photograph (students posing nude), 1883

Off With the Cloth

Anyone interested in realist painting will be fascinated by Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), whose disquieting endeavors, according to author Henry Adams, have been long misinterpreted. Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist (Oxford University Press, 2005) spills the beans. Now at last I know why, even as a mere child, I was attracted to Swimming (1883-85), The Gross Clinic (1875), and those paintings of sculls in the Schuylkill River, the idyllic ribbon that flows through Philadelphia's Fairmont Park.

Eakins, in one of those larger-than-life art history moments, pulled a loincloth off a male model in front of some female students at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art in 1886. We are not quite certain if this was the only reason he was dismissed. No minutes of the Academy Board were kept, but he apparently had the habit of pressuring both male and female students to pose in the nude to demonstrate their commitment to the nude and only the nude as the didactic tool for learning how to make art. He even offered himself in the buff. Rumors persisted that not only had he driven two women into madness, but that incest, bestiality and sodomy (the latter two items often interchangeable then in the popular mind) were not unknown among his panoply of vices and offenses, fancied or not.

Adamsdoes demonstrate that Eakins, contrary to Lloyd Goodrich's hagiographic monograph, was not a nice guy, but was rude, sloppy, slobbery (perhaps from therapeutic opiates), clearly bipolar and an exhibitionist/voyeur. Furthermore, although we are not privy to his bedroom proclivities, we know that, although married, he seemed to prefer the handsome Samuel Murray for studio companionship, country and seaside larking, and public dining. It was Murray, 15 years younger, and not his wife, who held Eakins' hand when he was dying. His wife, after Eakins' death, insisted he never painted from photographs and tried to change the title of Swimming (which reveals naked boys at play) to The Swimming Hole and then to the even more sentimental The Old Swimming Hole. The finished painting shows Eakins himself neck deep in the water staring at the winsome, buck-naked colts.

I am not sure that Adams is always correct in his interpretation of snapshots of Eakins: does he really look depressed? Is he a maniac, or is it the camera?

But Adams is certainly right in nailing Goodrich, once director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, for creating the deceptive view of Eakins as manly, honest, and forthright, posing him as virtuously all-American and the dubious precedent for the all-American representational painters Goodrich was promoting then: Reginald Marsh, John Sloan, Edward Hopper, etc. In reality, Eakins had a high-pitched voice, affected volunteer fireman's clothes and often painted in his underwear; failed his classes in Paris, told dirty jokes, was "feminine," was not exactly fond of women, was never much of an athlete, and drank a quart of milk with every meal. Adams, a bit of an amateur shrink, has fun with that last item, but does explain that milk was then a treatment for depression, at least according to the specialist Eakins visited after he was fired from the academy and had what we might call a nervous breakdown. The specialist in such things was a certain S. Weir Mitchell, author of Fat and Blood.

But Adams is certainly right in nailing Goodrich, once director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, for creating the deceptive view of Eakins as manly, honest, and forthright, posing him as virtuously all-American and the dubious precedent for the all-American representational painters Goodrich was promoting then: Reginald Marsh, John Sloan, Edward Hopper, etc. In reality, Eakins had a high-pitched voice, affected volunteer fireman's clothes and often painted in his underwear; failed his classes in Paris, told dirty jokes, was "feminine," was not exactly fond of women, was never much of an athlete, and drank a quart of milk with every meal. Adams, a bit of an amateur shrink, has fun with that last item, but does explain that milk was then a treatment for depression, at least according to the specialist Eakins visited after he was fired from the academy and had what we might call a nervous breakdown. The specialist in such things was a certain S. Weir Mitchell, author of Fat and Blood.

Crazy mother, overbearing father (wouldn't let anyone speak at the dinner table), lower-class background, homely wife, hardly any market for his paintings, Philadelphia air -- Eakins was a miserable fellow. The exhibitionism and love of embarrassing others is easily resolved into a big-time case of infantilism. There he is at the end in a wonderful photograph: fat-ass, bare-ass Eakins, around 1909, splashing into the river at his fish-house encampment, with who looks to be his devoted friend Murray standing by. Eakins, happy at last.

Samuel Murray and Thomas Eakins, c.1891

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Samuel Murray, 1889

The Love that Dares Not Speak Its Name: Photography

Adams, it should be noted, draws upon information from the Charles Bregler Thomas Eakins Collection (ironically now owned by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts). The collection, rediscovered in 1984, contains documents and many, many photographs from Eakins' studio, all rescued by his former student Bregler and squirreled away for years. From these it is more than clear that not only The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand (1879-1889) was photo-derived, with its up-to-date presentation of horse gait and blurred carriage wheels, but, until the late portraits, so was almost everything else.

Since Adams is mercilessly condescending to the catalog for the Philadelphia Museum of Art's 2001 Eakins retrospective, of course I had to dig it up. It is quite a tome (and, alas, like many catalogues, without an index); here Eakins remains the greatest American artist of the 19th century, the greatest unexamined American artist. There is no revisionism here, but details, details, and what amounts to promotion for Philadelphia's favorite artistic son. No warts, no shadows.

What is valuable, however, is Mark Tucker and Nica Gutman's chapter "Photographs and the Making of Paintings." They examined the photos in the Bregler Collection, used infrared analysis on the paintings, and looked close enough to see pinpricks and tick marks. Although he sometimes used the tried-and-true squaring-up method, internal evidence proves Eakins also employed a magic or catoptric lantern and traced projections, keeping his use of photography a secret. Photograph was apparently a bigger secret, I should add, than his relationship with hunky, swarthy Murray, a would-be sculptor of no discernable talent.

We also learn here (and in Adams) that Eakins patched together parts of various photographs; hence, in spite of his mechanical use of orthodox perspective, things don't quite match up. Like Vermeer (another "realist" favorite of mine who himself used a camera obscura), Eakins invented a photorealism that is dreamy and uncanny. Adams points to The Champion Single Sculls (1871), where everything seems lucid, proper; yet, although champion Max Schmit and his single scull are perfectly reflected in the water, the clouds are not.

Apparently Eakins wanted us to think that everything one needed to know was in the art: the usual cover-up. And Goodrich thought we needed a candy-coated he-man of a hero. Although in my view Eakins was one of the great ones, knowing just a little bit more about him makes his art a lot more interesting. Was he a victim of Philadelphia Puritanism? I'm not so sure. What would we think now of an art professor who made his students strip and pose for each other and took off his clothes too?

Thomas Eakins with female model, 1885 (Pennsylvania Acacemy of Art)

Thomas Eakins in four poses, c. 1885 (Pennsylvania Academy of Art)

Thomas Eakins with female model, c. 1885 (Pennsylvania Academy of Art)

For e-mail alerts of new postings: perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog